The odyssey that led the Parker clan to the edge of the Texas frontier started far to the east, in the state of Virginia. John Parker, leader of a fundamentalist Baptist church, married Sally White just after the revolutionary war. Their nomadic journey led them to Georgia, Tennessee, and finally Illinois, always looking for more and better land.

The odyssey that led the Parker clan to the edge of the Texas frontier started far to the east, in the state of Virginia. John Parker, leader of a fundamentalist Baptist church, married Sally White just after the revolutionary war. Their nomadic journey led them to Georgia, Tennessee, and finally Illinois, always looking for more and better land.

During these years, John and Sally had 14 children. Silas Mercer Parker, youngest of the Parker boys, was born in 1802 in Tennessee. He grew to manhood in Illinois and married Lucy Duty. Cynthia Ann was born in 1826, John in 1829, Silas Jr. in 1833 and Olena in 1834. In the early 1830s, John Parker again got restless, hearing of wide Texas prairies and free frontier life. The clan reached Conway, Arkansas in 1830 and petitioned Stephen F. Austin for a permit to settle in Texas. They were granted a league of land north of the present site of Groesbeck, on the Navasota River. James and Silas Parker completed a fort in the spring of 1835 and were joined by their father, brother Benjamin and four other families; 15 children and 22 adults. The fort was primitive, but formed a good pioneer defense complex of log pickets, 12 feet high, sharpened at the tip.

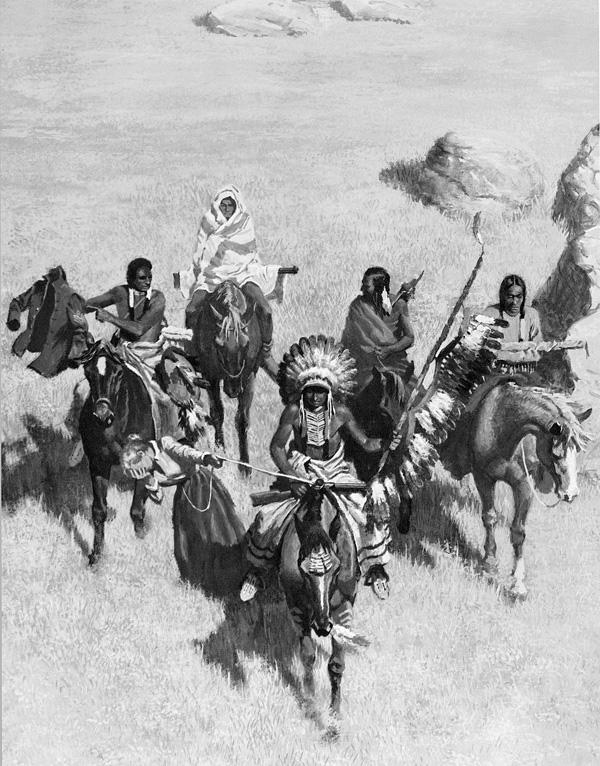

The Comanche were lords of the southern half of the Great Plains. Migrating out of the Pacific Northwest, their territory ranged from north of the Arkansas river in Kansas to south of the Colorado in Texas, east to a line from present day Oklahoma city, Waco and San Antonio and west to the high plains of New Mexico. Cousins to the Utes, Bannochs and Shoshoni, they were called Comanche, meaning enemy or “anyone who wants to fight me all the time.” Acquiring horses in 1705 from the Utes, their territory knew few limits. Spilling onto the Kansas Prairie by the mid-1700s they continued a slow migration ever southward into south-central Texas. The tribe, at its height around 1800, had 20 thousand members associated with six divisions. In the Southwest, the largest were the Penatika (Honey-eaters) with the Nokonis (Wanderers) just to the north. The middle Comanche tribes included, the Kolsotekos (Buffalo-eaters) along the Canadian River, the Vampaukas (Root-eaters) along the Arkansas River, and out on the Texas plains, the fiercest of all, the Kwahadi (Antelope-eaters). The Tenavi (Down-stream) rounded out the different divisions.

They were regarded as the best horsemen of the plains Indians, and the number of horses a Comanche owned indicated the extent of his wealth. Shorter than most plains Indians on foot, they looked awkward, but the moment they mounted their horses, they seemed at once transformed, and surprised the spectator with the ease and grace of their movements. It was for the purpose of acquiring horses that the Comanches came to the Navasota River that fateful day.

May 19, 1836, was a beautiful spring day. James Parker, Nixon, Plummer and several other men left to work the fields about one mile away. The gate to the fort was open; there was not a hint of danger. Ben Parker was near the gate about 9:00 a.m. when the cry came, “Indians.” Three of the Indians approached showing a white flag and making signs of friendship. The main party remained about 300 yards away in the tree line. At this time there were 6 men, 10 women and 15 children inside the fort.

Against Silas’ judgement, Ben went out to talk to the Indians to determine what they wanted. They pretended to look for a camping place with water and asked for a steer for food. Ben did not refuse them outright and returned to the fort. He told Silas that he felt the Indians were hostile and intended to fight, but he would go back out and try to avert it. Silas replied that if he went back, he was sure they would kill him, but Ben persisted and started out to talk. The women and children began to slip from the fort and head for the trees along the river.

As Ben reached the three, they immediately surrounded and speared him with their lances. The entire party rushed the front gate and forced their way in. In all the confusion, no one tried to close the gates, but tried to get away by running across the open area for the river. There is only one eyewitness account of the massacre at Fort Parker. Rachel Plummer wrote a narrative, published December 3, 1839, telling of her days as a Comanche captive. The following is her description of the massacre:

“When Uncle Benjamin reached the body of Indians they turned to the right and left and surrounded him. I was now satisfied they intended killing him. I took up my little James Pratt, and thought I would try to make my escape. I ran out of the fort, and passing the corner I saw the Indians drive their spears into Benjamin. The work of death had already commenced. I shall not attempt to describe their terrific yells, their united voices that seemed to reach the very skies, whilst they were dealing death to the inmates of the fort. I tried to make my escape, but alas, it was too late, as a party of Indians had got ahead of me. Oh! How vain were my feeble efforts to try and run to save little James and myself. A large, sulky looking Indian picked up a hoe and knocked me down, then took my child out of my arms. They dragged me back to the fort by the hair. Going past the corner, I heard an awful screaming near the place where they seized me, then heard Uncle Silas shout. I think he was trying to release me and in doing so lost his life, but not before he had killed four Indians. I was dragged to the main body of Indians, where they had killed Uncle Benjamin. His face was much mutilated, and many arrows were sticking in his body. I looked for my child but could not see him; convinced they had killed him, I expected to share the same fate. At length I saw him, an Indian had him on his horse; he was calling, ‘Mother, oh Mother.’ A Comanche woman came over and struck me several times with a whip, I assume to make me stop crying. I soon saw a party of the Indians bring my Aunt Elizabeth Kellogg and Uncle Silas’ two oldest children, Cynthia Ann and John; also some bloody scalps, among them I could distinguish that of my grandfather, John, by the grey hairs. They soon started back the way they had come, and as I was leaving, I looked back at the place where I was one hour before, happy and free, and now in the hands of a ruthless, savage enemy.”

The men in the fields heard the commotion at the fort about the same time as Mrs. Sarah Nixon arrived to tell of the coming of the Indians. Everyone started back to help. L.D. Nixon, though unarmed, ran toward the fort and met Lucy Parker, with her children, just as the Indians overtook them. They compelled her to lift Cynthia Ann and John up behind two warriors, then started back to the fort with her, the younger children and Nixon. They were about to kill Nixon when David Faulkenberry appeared, leveled his rifle and caused the Indians to fall back. With Lucy Parker and the two younger children behind him, they backed into the brush and trees by the river. The Indians made several dashes toward them, but the threat of Faulkenberry’s rifle always brought them up short. Silas Parker was killed trying to protect Mrs. Plummer. Samuel Frost and his son, Robert, were killed defending the women and children inside the fort. As Elder John Parker, Granny Parker and Elizabeth Kellogg attempted to escape to the trees, Elder John was murdered and horribly mutilated, his wife stripped, speared and left for dead, Elizabeth Kellogg captured. At twilight, Abram Anglin and Faulkenberry went back to the now silent fort. About halfway, they came upon “Granny Parker, crawling along more dead than alive. She was the only survivor; at the fort they found not a single individual alive, or heard a human sound. The next morning, the group secured some horses and set out for Fort Houston, leaving only the dead at Fort Parker.”

The war party traveled northwest with their captives, Elizabeth Kellogg, Rachel Plummer, James Pratt Plummer, Cynthia Ann and John Parker. Around midnight they stopped to celebrate the victory. The torture endured by the captives is again described in the narrative by Rachel Plummer.

“They tied a plaited thong around my arms, drew my hands behind me and tied them so tight the scars can be seen to this day. They tied a thong around my ankles, and drew my feet and hands together. They turned me on my face so I was unable to turn over. To add to my misery, they brought my little James so near me that I could hear him cry. He would call for mother; and often his voice weakened by the blows they would give him. I could hear the blows, I could hear his cries; but oh, alas could offer him no relief. The rest of the prisoners were brought near, but we were not allowed to speak to one another. My aunt called me once and I answered her; but, indeed, I thought she would never call or I answer again, for they jumped with their feet upon us, which nearly took our lives. Often did the children cry, but were soon hushed by such blows that I had no idea they could survive. The Indians commenced screaming and dancing around the scalp pole, kicking and stamping us without mercy.”

Along toward morning the ravaging ended, leaving the five more dead than alive. The different tribes parted, dividing the prisoners among them. Elizabeth Kellogg was sold to the Keechies and by them to the Delawares, who, six months later, surrendered her to General Sam Houston for $150.00. Rachel Plummer and her son, James, were separated, and she remained in captivity for 18 long months before being ransomed. She returned to her father’s house on February 19, 1838, but lasted only one short year before dying on February 19, 1839, never knowing what had become of her son. James Plummer was kept for six years, then ransomed back to his Uncle James Parker at Fort Gibson, Oklahoma. John Parker was taken south by the Penatika band and grew up a Comanche warrior. While on a raiding party into Mexico, he met and fell in love with a Mexican girl, Donna Juanita. He came down with small pox and the tribe abandoned him on the Llano Estacado. Donna Juanita demanded to be left with John and nursed him back to health. John, married to Donna Juanita, refused to rejoin the Indians. Instead he went to Mexico and became a rancher. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he served in a Mexican company in the Confederate army, but refused to cross the Sabine River. After the war he returned to his family, where he lived until his death in 1915.

Cynthia Ann was taken by Pa-ha-u-ka’s band of the Kolsotekos and disappeared into the Texas wilderness for four years. Her early years with the Indians must have been incredibility difficult. From a childhood where she was not required to perform a lot of hard chores, she suddenly was thrust into an environment where she shouldered an Indian women’s burden. Around 1840, Colonel Leonard Williams, a trader, and his Delaware Indian guide came upon the tribe camping on the Canadian River. Cynthia Ann was about 14 years old, but Colonel Williams recognized her and talked to the Indians about ransom. The fierceness of the family leader indicated that the subject was dangerous. Colonel Williams kept trying until the Chief prevailed upon the family to allow him to talk to Cynthia Ann. She had been cautioned to tell nothing of her captivity and heeded the warning. As Captain Williams told her stories of her mother and family she listened, however, would not speak nor interact with the white men. Her only outward sign was a continued anxiety as she wrung her hands and cut her eyes to her Indian family. Her lips trembled, her eyes filled with tears, but she would send no message to her loved ones. Colonel Williams finally shrugged his shoulders and the traders packed up and left.

Throughout the 1840s, snippets of information concerning the whereabouts of Cynthia Ann Parker would come to the Indian agents. In 1847, Robert S. Neighbor reported she was held by some Tenavi Comanches, who ranged along the upper Red River. He sought to cultivate these middle Comanche but could not find Cynthia Ann. She simply faded back behind the curtain of Comanche life.

Cynthia Ann grew to womanhood and was given the name of Narua. She was a stranger now to every word, every syllable of her native tongue. By the mid-40’s, a Comanche chief by the name of Peta Nocona took her as his wife. Was this union mutually agreed to by both parties, or did the Comanche chief simply take her to his tepee since she was regarded as a slave? There is no documentation or word of mouth to answer this question either way. What is known is that she was completely devoted to her children and could not be persuaded to consider leaving them. This was attested to by a report turned in by a Captain R.B. Macy, of the Rangers, in the mid-1850s.

“There is at this time a white woman among the middle Comanches, by the name of Parker, who with her brother, was captured when they were young children, from their house in the eastern part of Texas. This woman has adopted all the habits and peculiarities of the Comanches, has an Indian husband and children and cannot be persuaded to leave them. She stated that all she held most dear were with the Indians and there she would remain.”

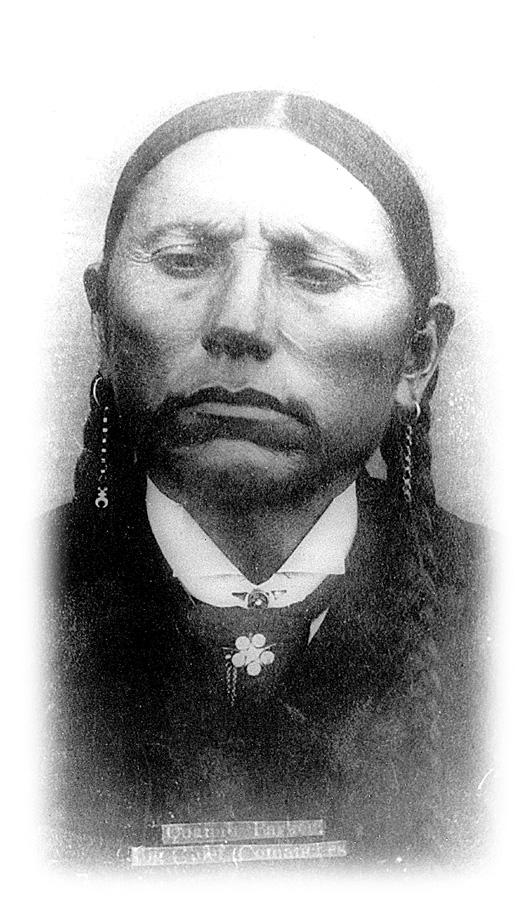

It appears that Cynthia Ann and her family were part of the Nokoni (Wanderers) or possibly the Detsanayuka (Bad Campers) band at this time. Cynthia Ann and Peta Nocona had three children; Quanah, born around 1848, Pecos about six years later and the little girl, Topasannah (Prairie Flower), in 1859.

In the fall of 1860, Peta Nocona lead a raid into the central Texas counties of Palo Pinto and Parker. The public outcry was swelling each day among the settlers on the Texas frontier to move against the Comanche. A force of Texas Rangers was immediately organized under the command of Captain Sul Ross, augmented by a detachment of the second Cavalry, plus volunteer citizens. They found the tribe camped on the Pease River, in present day Foard County, preparing for the last buffalo hunt of the year. In the early afternoon, a severe dust storm blew in and interrupted the efforts at setting up camp. Since the weather conditions were so bad, no guards were posted and everyone took cover. The forces from Parker County struck and completely surprised the tribe. Capt. Ross’ forces did not know whose camp they had attacked and could not tell that most were women and children from the robes covering their faces.

As the attack started, the Indians began to mount horses to get away. Cynthia Ann, carrying her baby girl, was on one horse while her servant, Joe Nocona, and a young girl rode another. Capt. Ross and Lieutenant Kelliheir had singled out the two and were in hot pursuit. Capt. Ross shot at one horse and killed the young girl behind Joe Nocona. The next few shots knocked the Mexican slave off his horse. He rose, in spite of his wounds, walked to a small tree, and started singing his death song. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Kelliheir had grabbed the reins of Perlock’s horse and stopped it not far from where Joe Nocona was dying. He called to Capt. Ross, when the robe fell from her face, “This ain’t no Indian. It’s a white woman with blond hair and blue eyes. She’s got a baby with her.” Cynthia Ann Parker had been recaptured.

Cynthia Ann couldn’t understand them; she was sure they were going to kill both her and her baby. She tried to make them understand by saying the only two words she knew, “me merican, me merican.” She continued to cry and sob as they discussed what to do with her. The rest of the tribe by now had fled or been killed; there was no one left to help. Capt. Ross called his Mexican interpreter to explain she must not be afraid, they knew she was white and would take her back to her people. The men took her to Fort Cooper, near the present site of Albany, Texas. Captain G.E. Evans, commander of the post, turned Cynthia Ann over to his wife. The officers’ wives cleaned and bathed both Cynthia Ann and her baby, Prairie Flower, and dressed them in new clothes. Cynthia Ann didn’t like the stiff, binding clothes and had a hard time eating because the food didn’t taste right. She also refused to sleep on a soft bed, instead used the floor with a simple blanket.

Colonel Isaac Parker left Fort Belnap to travel to Fort Cooper. The officer’s wives tried to explain to Cynthia Ann that her uncle was coming, but she could not understand. She would nod, but had no idea what they meant. She was 34 years old at this time and had not heard the English language for 20 years. Colonel Parker was convinced at once that this had to be his long lost niece. He and the Mexican interpreter tried to talk to her through the long afternoon, but she could remember nothing about her family or former life. Nothing seemed to penetrate the solid wall of the Indian environment until, in despair, he rose to leave and said, “I was sure it was Cynthia Ann.” This was the trigger that sprung open the door to the past. She straightened herself in her seat, and patted herself on the breast, and said, “Cynthia Ann, Cynthia Ann.” A ray of recollection sprung up in her mind, that had been obliterated for 25 years. Her very countenance changed, and a pleasant smile took the place of sullen gloom.

Colonel Parker took Cynthia Ann to his Birdville home and immediately started her reintroduction. The change was difficult since she remembered so little of the English language. He talked to her constantly about the past, trying desperately to make her remember her white family from so long ago. It was hard for Cynthia Ann, afraid of the strange voice and not understanding what he was talking about. Time is a great healer bringing a day when she suddenly called him, “Uncle Isaac.” She accompanied her uncle to Austin to attend a session of the Texas Legislature. It was a terrifying experience. She was sure they were meeting to kill her and her baby. The ladies assured her they were only talking about seceding from the Union. The sympathetic legislature granted her $100 dollars per year for five years, a league of land, and appointed Isaac D. Parker her guardian. Her main worry continued to be about her two sons. When she heard about raids, her feelings resurged, knowing her sons might be killed. She talked about her sons all the time, but rarely mentioned her husband, Peta Nocona. When her uncle brought the news about Nocona’s death, she made no movement, no indication of sorrow, and only said, “Chief, he whip too much.” This was the last said about her Comanche husband; his memory was past and gone.

She had ceased to talk about returning to “her people”; that time was over. The burning passion in her breast continued to be her maternal concern for her two sons, and she continued to cherish the hope that after the war she could go and reclaim her children. A trader returning from traveling among the Comanche brought the news of Pecos’ death causing Cynthia Ann to withdraw more. She occupied the time by spinning and weaving articles for the confederate Army, and spending many hours of playing with little Prairie Flower. The little girl was now talking, with Cynthia Ann teaching her about life with her father’s people. She knew that Prairie Flower would grow up with white people and didn’t want her to forget the Indian ways.

In 1864, Cynthia Ann’s world collapsed when Prairie flower got sick with Spinal Meningitis. Prarie Flower’s young body could not overcome the illness and she died in two days. A heart broken Cynthia Ann moved to her sister’s home to recover from the death of her baby. It was to no avail. She pined away in mourning for her two lost children until she died in 1870. Cynthia Ann was buried with tiny Prairie Flower in the Fosterville Cemetery in Anderson County.

Cynthia Ann would never know of the greatness her remaining son achieved. He became the leader of the Kwahadi, the last Comanche division to surrender to the reservation in June 1875. A great leader in war, he became even greater in working for the future of his people. Quanah had never forgotten his mother and began to actively search for her. With the help of cattleman Burk Burnett and Charles Goodnight, he located his Parker relatives and began to work toward moving her remains to the Oklahoma Reservation. On December 10, 1910, she was reburied with Prairie Flower at Cache, Oklahoma. In only two short months, on February 23, 1911, Quanah followed her in death.

The three were later re-interred at Fort Sill military cemetery. The Commanding General of the base gave the following oration:

“Her unfailing devotion to her children and Quanah’s devotion to her, is part of Southwest history and American tradition. She is a shining example of Motherhood in adversity everywhere.”

Mother, son and daughter now lie side by side; the final resting-place of Pecos is known only to God.

Don Smart, is a retired Aerospace Engineer who now has time to pursue his other “loves,” history and writing. He lives and works in Erath County, Texas.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy of Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries –

– Courtesy of Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries –