— All Images Courtesy Paramount Pictures —

Who is the best marshal they have?”

“The meanest one is Rooster Cogburn. He is a pitiless man, double-tough, and fear don’t enter into his thinking.”

“Where can I find this Rooster?”

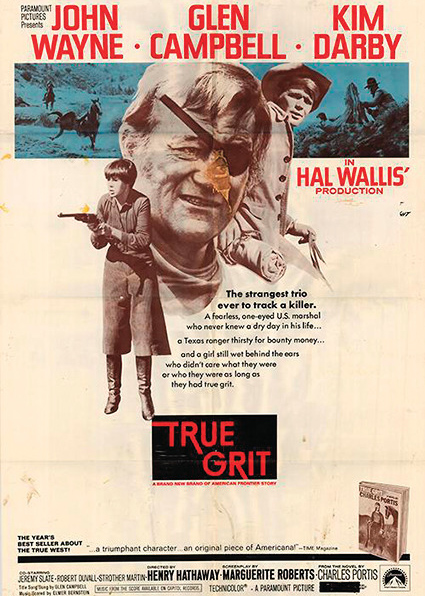

Half a century ago, audiences awaited the premiere of True Grit with some trepidation. After all, its star, John Wayne, had lost a lung to cancer. He’d done movies since, but none as vigorous as this, and his recent film, The Green Berets, had received a tepid-to-terrible reception due to its gung-ho support of the nation-polarizing Vietnam War. Joyously, his fans’ doubts were misplaced. It was a wonderful story, a wonderful film, and Wayne’s performance would earn an Oscar.

True Grit is the story of 14-year-old Mattie Ross’s battle for justice after her father’s murderer escapes into Indian Territory. Mattie hires notoriously tough and disreputable Rooster Cogburn and, joined by Texas Ranger Le Boeuf, they try to bring the killer back to Judge Parker’s court for trial.

When Wayne read Charles Portis’s novel, his Batjac Productions immediately bid for the film rights, only to be outbid by legendary producer Hal Wallis, who four years earlier had produced The Sons of Katie Elder with Wayne! Duke confronted Wallis and learned to his surprise that Wallis had bought it intending for Wayne to star.

To write and direct, Wallis brought in the pair he’d teamed for 5 Card Stud, Marguerite Roberts and Henry Hathaway. Roberts was ideal for Westerns; her grandfather had been a sheriff, her father a town marshal. “Daddy put me on a horse before I knew how to walk,” she would tell Tina Daniell. “I was weaned on stories about gunfighters and their doings, and I know all the lingo, too.” She’d scripted pictures for Gable, Peck, Mitchum and Tracy, but for a decade, she hadn’t written anything that reached the screen. She’d joined the Communist Party in the 1930s, quit in the ’40s, but when questioned by the House Committee on Un-American Activities, she refused to name names and was blacklisted. Would Wayne, who’d supported the blacklist, even read her script? Yes; and often thereafter he’d say it was the best screenplay he’d ever read. Portis, who visited the set, notes, “The screenplay stayed pretty close to the book. I noticed that…Hathaway used the book itself, with the pages much underlined, when he was setting up scenes.”

Hathaway began as a child actor in Allan Dwan Westerns in 1909. By age 14 he was a prop-boy at Universal, and after serving in the Army in World War I, was back in Hollywood, assisting masters like Victor Fleming, Joseph von Sternberg and Ernst Lubitsch. Between 1932 and ’33 he directed seven Zane Grey Westerns for Paramount starring Randolph Scott.

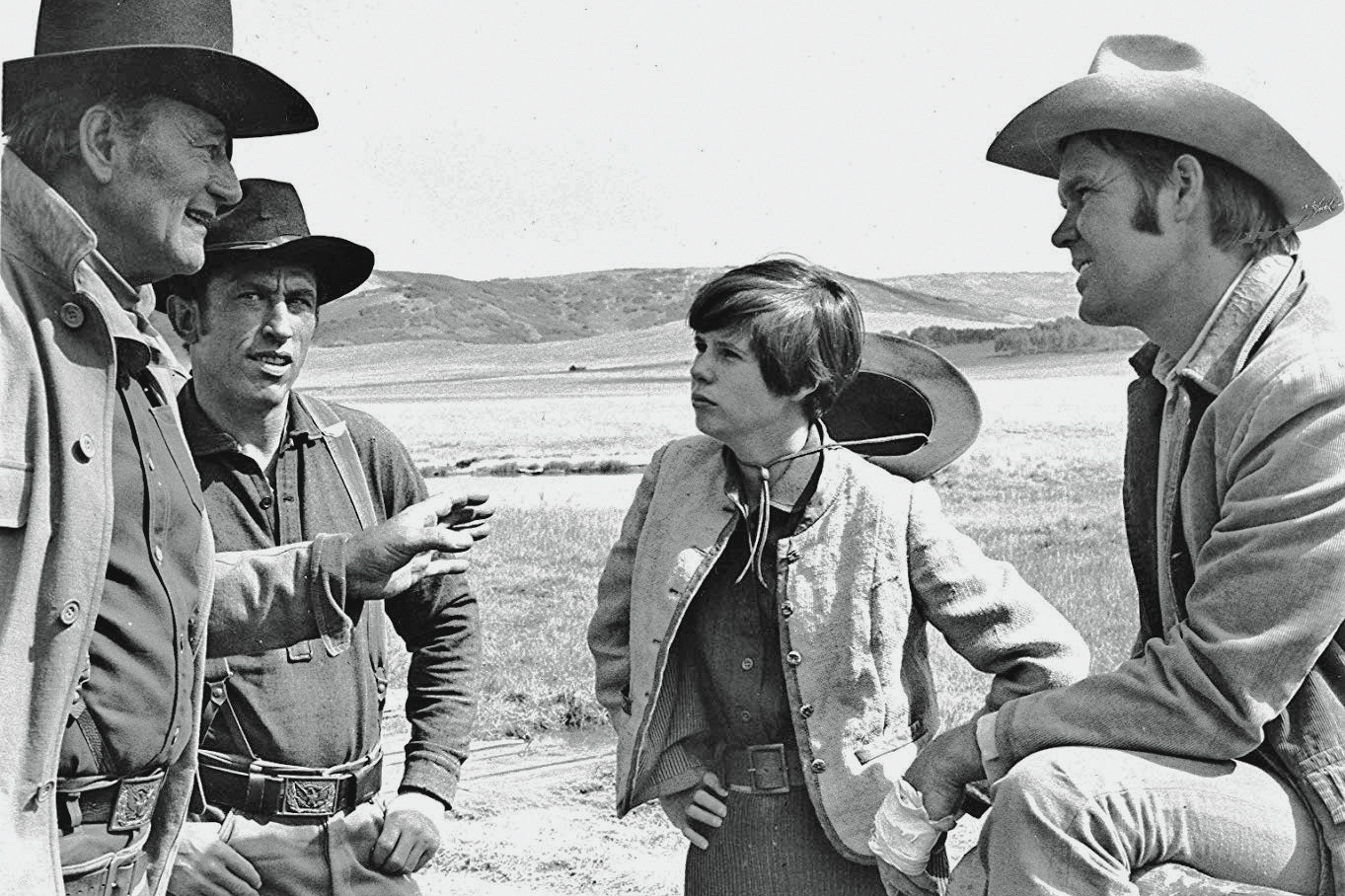

Hathaway had known Wayne since they were both silent-movie prop-men, and he’d already directed Wayne in five movies. But, as Hathaway himself explained it, “To be a good director, you’ve got to be a bastard. I’m a bastard and I know it.” Stuntman Gary Combs, who’d come to True Grit straight from The Wild Bunch, explains it more generously. “Henry knew everybody’s job on the set just as well as he did his own, ’cause he’d been around for so long.” He had no patience and screamed at actors.

Rosemary’s Baby star Mia Farrow had agreed to play Mattie, but Robert Mitchum, who’d made 5 Card Stud with Hathaway, warned Farrow against working with him. Farrow asked Wallis to replace Hathaway with Rosemary’s Baby director Roman Polanski. That was the end for Mia, who years later would tell The Independent that turning down the roll of Mattie “was the worst career choice I ever made.” Wayne asked Katharine Ross, his co-star in The Hellfighters, about the role. She recalls: “I read the book, and she was 14, and I thought that I was too old, so I didn’t do it. What an idiot.” She made Butch Cassidy instead.

Then Wallis saw Kim Darby in an episode of Run for Your Life, and knew he’d found Mattie Ross. Although 22, with a newborn baby, and divorcing James Stacy, she gave a convincing performance as the feisty 14-year-old.

For the role of Le Boeuf, Wallis cast Elvis Presley, who’d shown his acting talent in the Western, Flaming Star. All that Col. Tom Parker, Elvis’ Svengali, demanded was that Elvis be billed above Wayne. Elvis was out, and in was country singer and first-time actor Glen Campbell.

Puzzlingly, Jay Silverheels, the Lone Ranger’s Tonto, has a no-lines role as one of three men hanged when Mattie first arrives at Fort Smith. A look at the novel and screenplay reveals that originally each man had a speech, drawn from newspaper accounts, but all were cut from the film. It was a memorable scene for Combs, who doubled for Campbell and Robert Duvall, and was also up on the scaffold. “[We wore] leggings with cables that went under your instep, and up to a harness on your hip, so when you drop, you hit on your insteps, not your neck.” They wore hoods. “The trapdoor was pretty small, and when you drop, you don’t want to hit your head. I’d pulled the hood out in front so I could see the floor. Henry’s rolling camera, and as hangman Guy Wilkerson comes by me, he jerks my hood down! My hands were tied behind my back, but they just had these little [fake] things wrapped around. So I snuck my hand out, pulled the hood out, and nobody saw it. Because I didn’t want to go through that hole off-center and catch my nose on the edge.”

The story was set in Arkansas, but Portis learned that during the making of How the West Was Won Hathaway had “marked down that stand of yellow aspens in the mountains near Montrose, and was determined to make [a] Western there.” It was shot largely in the tiny town of Ridgway, Colorado, where Portis got to meet Duke. “Wayne was no letdown. He was actually bigger than his image on the screen, both in stature and presence.” Wayne was, in fact, so big that casting notices for extras said they had to be at least 5’10”, so they wouldn’t look like munchkins next to him.

For Luster Bayless, wardrobe man on a dozen Wayne movies, the smallest item was his biggest challenge: the eye patch. Wayne insisted on being able to see through the patch, and after much experimentation, Bayless concocted a patch using window-screen mesh and gauze. There are always duplicates for key wardrobe items, but, he recalled, “John wanted a fresh patch every day, because they got dirty.” Also, Wayne had put on weight. “He had some trouble getting on and off the horse. I had a stretchy fabric for his pants, that made it easier.”

One unanticipated problem was just how scared Darby was of horses. Something as simple as leading her horse in a natural way was so difficult for her that, Combs remembers, “Henry went nuts. He got a fire hose—he was gonna hose

her down, and the assistants came and calmed him down, and finally we got the shot.” Nearly all of her riding was done by stuntwoman Polly Burson. “They made a mask of my face out of clay,” Darby told the L.A. Times, “and she would wear that.”

Glen Campbell was also not too experienced on a horse, “so they gave me a Shetland pony,” he’d said. It wasn’t quite that, but it did, purposely, look silly next to Wayne’s steed. Campbell wasn’t an experienced actor, “but the Duke promised that he could drag me through it alright.” The modest Campbell often joked that his own poor acting made Wayne look so good that he won an Oscar.

They’d shot most of the final scene, with Mattie offering Rooster a place in her family’s cemetery, but when they returned the next morning, there were four inches of snow on the ground. It looked so beautiful that Hathaway scrapped the previous day’s footage, and shot it all over again. “Wayne wanted to jump the horse over the fence,” remembers Combs. “So we took [stuntman] Chuck Hayward’s falling horse, Twinkle Toes. He looked just like the horse that Duke was riding. Hayward and I were on either side, out of camera range, to protect him, but he jumped over the fence and rode off. He was fine.”

John Wayne’s granddaughter, Anita La Cava Swift, had seen his movies at home. “But,” she said,” the first one I saw in a theater was True Grit. My very best friend was Alfred Hitchcock’s granddaughter, and I didn’t know my grandfather was

as famous as he was until he won the Academy Award, and Alfred Hitchcock said, ‘Make sure you tell your grandfather that I said congratulations,’ I thought, okay, my grandfather is big-time!”

John Wayne left the Sonora set of Undefeated to attend the Academy Awards and receive his Oscar. When he returned, he was greeted by a strange sight: Bayless had outfitted every member of the cast and crew with an eye patch to welcome him back.

There were attempts to re-create the magic of True Grit over the years, including a sequel, Rooster Cogburn, co-starring Wayne with Katharine Hepburn, a reworking of her African Queen, with Wayne in the Bogart role; and the TV movie True Grit—A Further Adventure, starring Warren Oates. They’re both watchable, but only the 2010 remake by the Coen brothers holds a candle to the original.

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com