When the Civil War broke out in 1861, one foe the Confederacy did not anticipate was the Mescalero Apaches of western Texas and central New Mexico. Federal forces pulled out and headed east leaving the territory wide open.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, one foe the Confederacy did not anticipate was the Mescalero Apaches of western Texas and central New Mexico. Federal forces pulled out and headed east leaving the territory wide open.

Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor of the Department of Texas of the Confederate Army was ordered to take seven companies of the Second Texas Mounted Rifles and garrison some of the abandoned forts in west Texas, which included Clark, Hudson, Lancaster, Stockton, Davis and Fort Bliss, which was just outside of El Paso.

The 87 men of Company D were assigned to Fort Davis, which was east of Fort Bliss, under the command of Captain James Walker, a 48-year-old physician from Lavaca County, Texas.

Baylor had bigger plans, however, and pressed his offensive into New Mexico Territory to take it for the Confederacy. To do so, he needed all the men he could get, and soon Captain Walker moved on to New Mexico, leaving two young second lieutenants, Reuben Mays and William White, in command at Fort Davis with 25 men.

While the Confederates initially enjoyed success against the Federal forces in New Mexico, they had serious problems to their rear. The Mescalero Apaches were also enjoying success as they attacked Confederate supply trains headed for New Mexico. They had all but halted traffic between San Antonio and Mesilla, New Mexico, where Baylor had his headquarters. The Apaches were also killing Confederate scouts. Baylor realized something had to be done, so he ordered Confederate Commissioner James McCarty, currently at Fort Davis, to seek out the Mescalero leaders and establish some sort of terms to keep the Indians from attacking the Confederate supply lines.

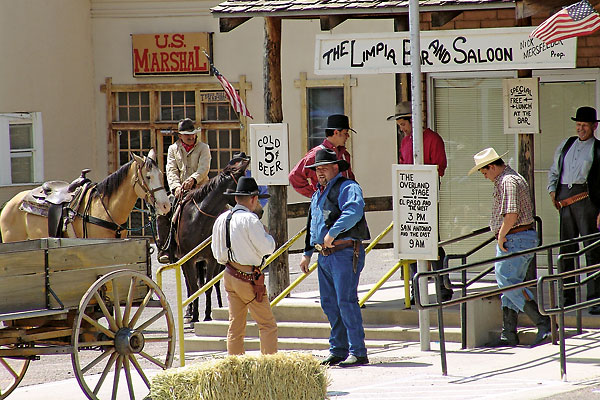

One crafty Mescalero leader, Nicolás, was known to have an absolute hatred for the white men. However, with the promise of food and gifts, he agreed to meet with McCarty at Fort Davis. The meeting appeared to be successful, and McCarty invited Nicolás to accompany him to El Paso and meet with James Magoffin, the Confederate Peace Commissioner. Again, there would be food and gifts and Nicolás would get to ride in the white man’s stagecoach. The Apache leader grinned. That would be a good story to tell his warriors.

Nicolás made the trip and met with James Magoffin and John Baylor—who also lost no love for their enemy. The Mescalero leader received presents, and it appeared that peace would reign between the Confederacy and the Mescaleros. The white men made eloquent speeches; Nicolás had something to say in turn.

“I am glad I have come. My heart is full for my white brothers. They have not spoken with forked tongues. We have made a treaty of peace and friendship. When I lay down at night, the treaty will be in my heart and when I arise in the morning it will still be there. And I will be glad I am at peace with my white brothers.”

Magoffin made arrangements to provide rations and blankets for the Mescaleros, and they would join the Confederates as scouts. James McCarty had to be quite pleased as he and Nicolás rode in the stagecoach back to Fort Davis. Not only had he solved the Mescalero problem, but now the Confederacy had new manpower to add to their ranks. McCarty and Nicolás talked amicably during the trip. Then, about 20 miles east of Fort Davis, Nicolás suddenly pulled McCarty’s pistol out of the holster and leaped out of the rumbling stagecoach. Before McCarty could say anything, Nicolás disappeared into the night.

McCarty sat quietly and thought about it. Perhaps things weren’t quite as blissful as he had believed.

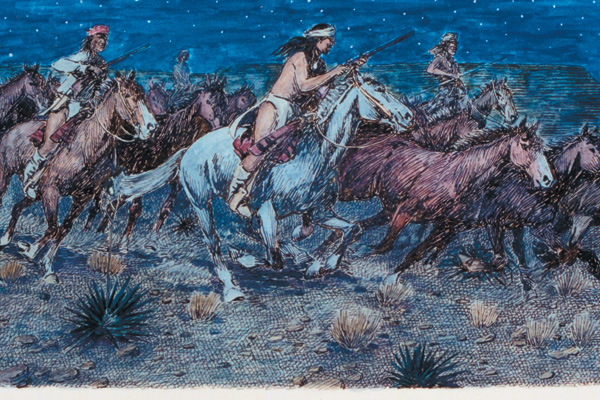

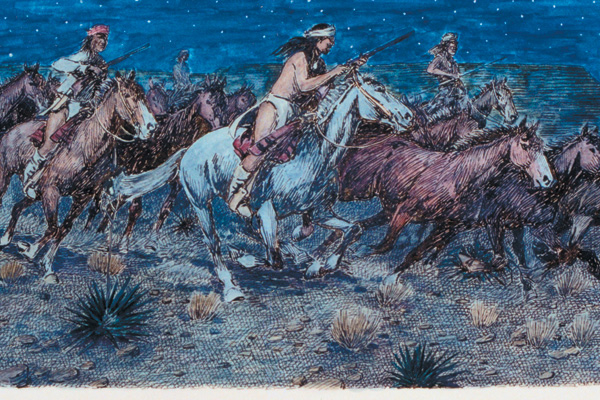

A few nights later, on August 4, 1861, Nicolás and two other Mescalero leaders, Antonio and Espejo, led 200 of their warriors to the Fort Davis pasture. They slaughtered a large number of cattle and took about 100 horses. The next day, a man showed up at Fort Davis and reported that the Mescaleros had attacked the ranch of Manuel Múzquiz, about six miles away, killing three men and stealing most of their livestock.

No doubt about it, Nicolás wasn’t living up to the agreement and something had to be done. That same day, Second Lieutenant Reuben Mays led a detachment out of Fort Davis to deal with Nicolás and his Mescaleros.

Mays really wasn’t the best man to be chasing after Apaches, and he didn’t have enough men. He was a 26-year-old man from Lavaca County who had no military experience at all—he was just fulfilling his military obligation. Prior to the war, he had been a carpenter who studied law on the side. When he rode out of the fort on that hot Texas day, he led six troopers and seven civilians. All of his soldiers were just like he was. They were young men from Lavaca County who had never fought in battle. They carried a variety of rifles, pistols and knives. Mays had a Mississippi long rifle, a Bowie knife and a watch, all of which he borrowed from Lieutenant White. Among the civilians were John Woodland, an Englishman who clerked for the post sutler, and John Deprose, a Canadian teamster. Three post guides went along as well —John Turner, Juan Fernández and an unidentified Mexican. Fernández didn’t speak much English.

The Texans followed the Mescaleros’ trail for several days, and in the late afternoon of August 10, they made camp. They had no idea they were just three miles from the Mescalero camp. However, as they scouted around the area, they found some horses and stolen livestock grazing in a small canyon. As they started rounding them up, they saw the Mescalero camp. It was almost too good to be true. They had actually stumbled onto the Indian camp.

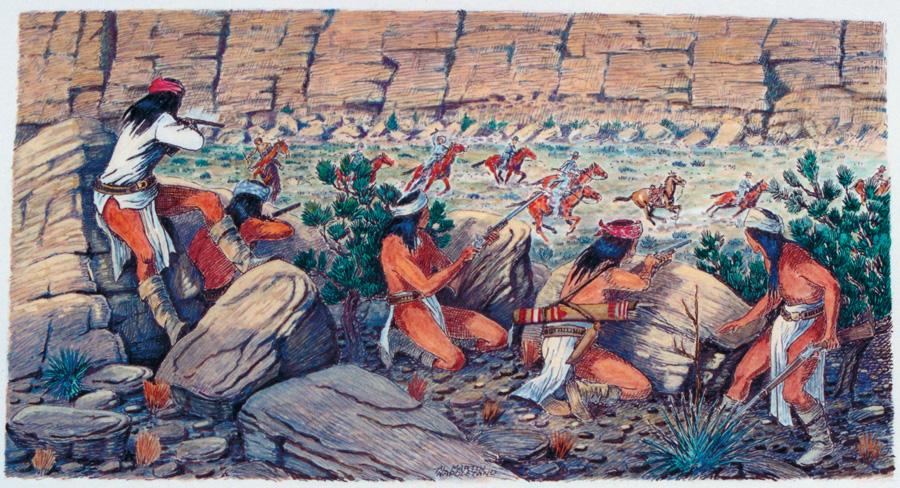

Most of the young Texans wanted to charge up the canyon and hit the Indians in a hard, surprise attack. Mays had to think about it. Did they really have the element of surprise? After all, they had been rounding up livestock for a while. Was it possible the Mescaleros had seen them? Reuben Mays didn’t think it was a good idea. Neither did Juan Fernández. But the young, cocky Texans from Lavaca County wanted to attack; after all, they had been left out of battle with the Yankees, and now they wanted a fight—the Indians were just up the canyon. Mays relented against his better judgement, and they rode into the canyon.

They didn’t get very far. In fact, the Mescaleros had been watching their every move. The canyon suddenly roared with gunfire and Mays saw several of his men topple out of their saddles. Apaches seemed to be behind every rock and tree, materializing right out of the ground. Mays yelled for a retreat. The Texans jerked their reins and dug in their spurs. Mescalero warriors jumped on their horses and immediately gave chase. At least 100 Apaches now pursued about 10 frightened Texan Confederates. A few more of Mays’ men were dropped in the running battle.

When the white men got back to their camp, they jumped off their mounts and took up a defensive position behind a large boulder. The Mescaleros quickly swarmed and had the Texans surrounded. The young men fought for their lives, but the odds were overwhelming. One by one, the remaining white men slumped over, or flayed out, when bullets smacked into them. Mays was hit in the arm, the bullet breaking the bone. He handed the Mississippi rifle to Fernández, since he couldn’t operate it with one arm, and continued fighting with a pistol until he was killed. Fernández found a rock ledge, climbed up to it and hid under it with the seriously wounded Jack Woodland. A few minutes later, the dust settled on that hot Texas evening, and the moon shone down on a grisly scene.

On August 15, Juan Fernández, exhausted, dirty and bloody, showed up at Fort Davis. The worried Texans were eager to hear what had happened to their comrades. In his broken English, the Mexican tried to tell them. Lieutenant White sent out a relief column of 19 men, both soldiers and civilians. Fernández led them to the site of the massacre, evidence everywhere that a battle had taken place: They found dead horses including the one Mays rode. They also found his pistol and the bloodstained waistband of his corduroy pants. There were other hats, boots and articles of clothing. The only corpse they found was the badly decomposed body of John Deprose—it could only be identified by the clothing. Juan Fernández climbed up to the rock ledge where he had left John Woodland. He, too, was gone, but his pistol was left behind.

The Mays fight is one of the biggest mysteries in Western lore. Apaches usually stripped their victims, took weapons, mutilated the bodies and left them for others to find. This time it was the reverse. Weapons and clothing were found, bodies never were.

Tim Simmons, in addition to writing for Wild West, Persimmon Hill, and numerous other magazines, has also written two books, Up From The Ashes and Brothers of the Pine.

Photo Gallery

– True West archives –