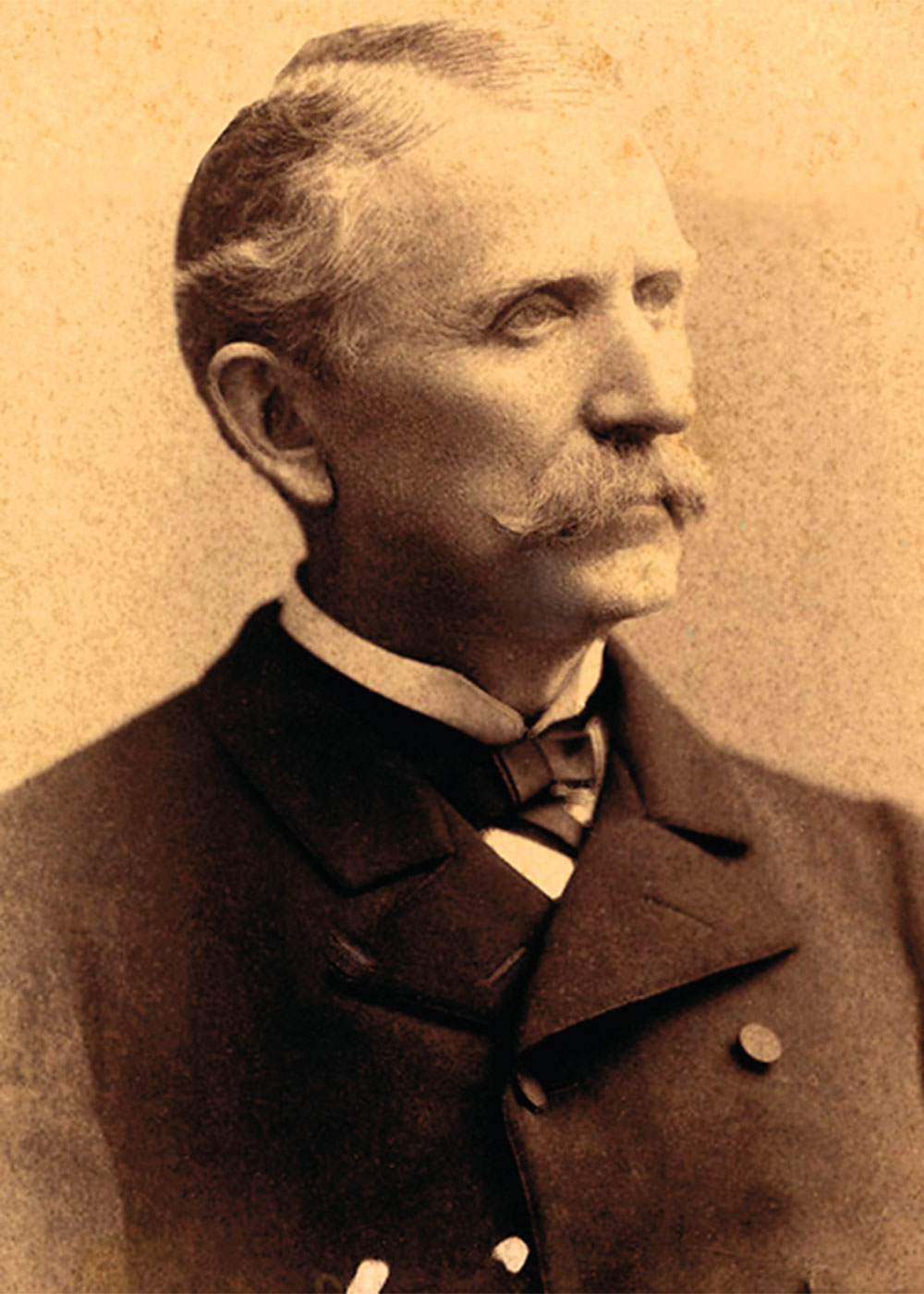

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

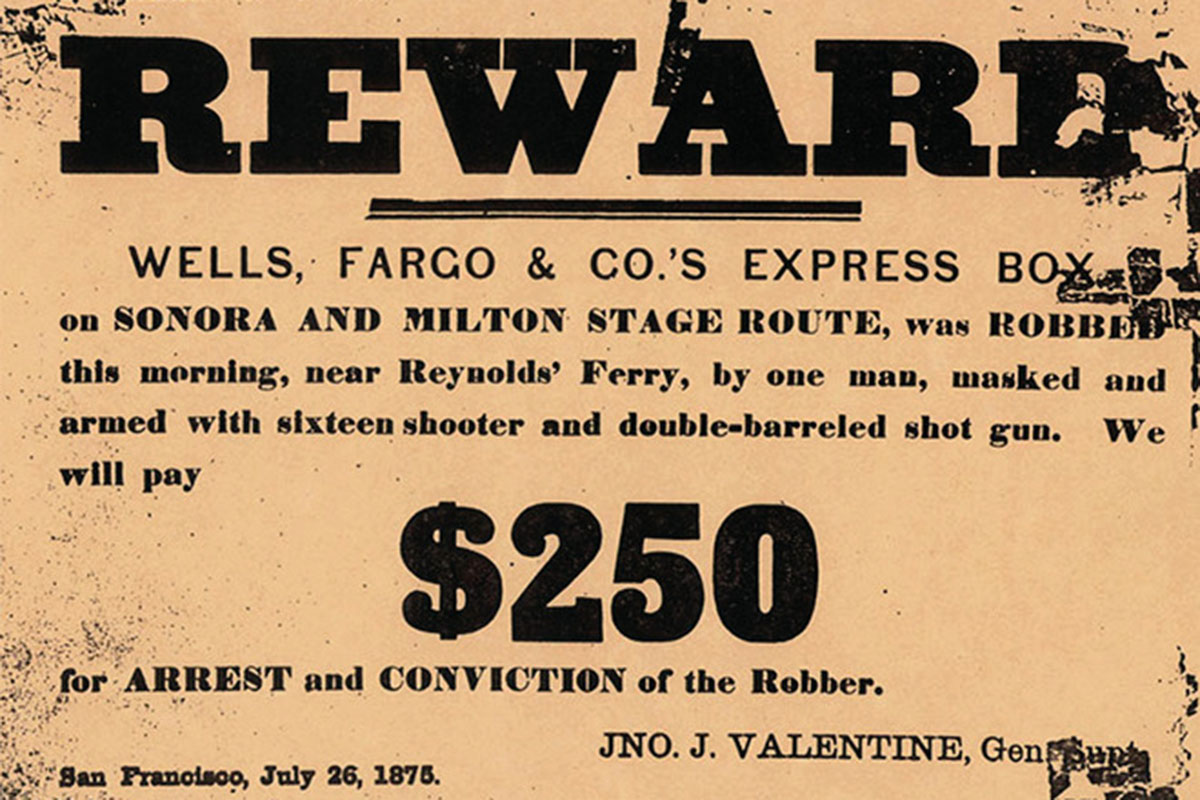

Wells Fargo & Company’s Express was one of the most important businesses on the Western frontier. The company began as a local mail delivery service during the California Gold Rush in 1852, a time when the U.S. Post Office was all but nonexistent in the mining camps. Because Wells Fargo was safe and, unlike the Post Office, made all losses good, it grew rapidly throughout the West, connecting towns big and small, and eventually became the country’s largest express carrier. Robbers followed the money, and during the late 1850s stagecoach holdups became increasingly common in California. Wells Fargo began hiring armed guards, later called “shotgun messengers,” to accompany treasure shipments. Contrary to popular belief, they did not guard stagecoaches; they protected Wells Fargo’s strongboxes. And the title “shotgun messenger” did not come into popular use until the 1870s. Such terms as “riding shotgun” and “shotgun rider” were invented by 20th-century novelists and were unknown in the Old West.

— True West Archives —

By the mid 1870s the company had 35 shotgun messengers. That number grew to 110 in the early 1880s, and then 200 by 1885. By 1918 the company employed 3,000 shotgun guards, mostly on railroads. Every Wells Fargo railcar had at least one armed messenger, and often a messenger’s helper. Of these guards, Wells Fargo’s chief detective James B. Hume explained, “In all my experience, there has never been an occasion when a regular shotgun messenger showed the white feather no matter what the odds against him or the promise of danger might be. They are the kind of men you can depend on if you get in a fix, with the certainty that they will pull you through or stay by you to the last.”

The shotgun messengers who rode for Wells Fargo in the Wild West were expected to risk their lives to protect the company’s treasure boxes. Their work was dangerous. Between 1855 and 1915, at least 53 Wells Fargo expressmen—most of them messengers—died in the line of duty. Nineteen were slain by outlaws or bandits, four were accidentally shot, four more died in shipwrecks and steamboat explosions, and many of the others perished in train wrecks. But few of them took as many risks as Mike Tovey.

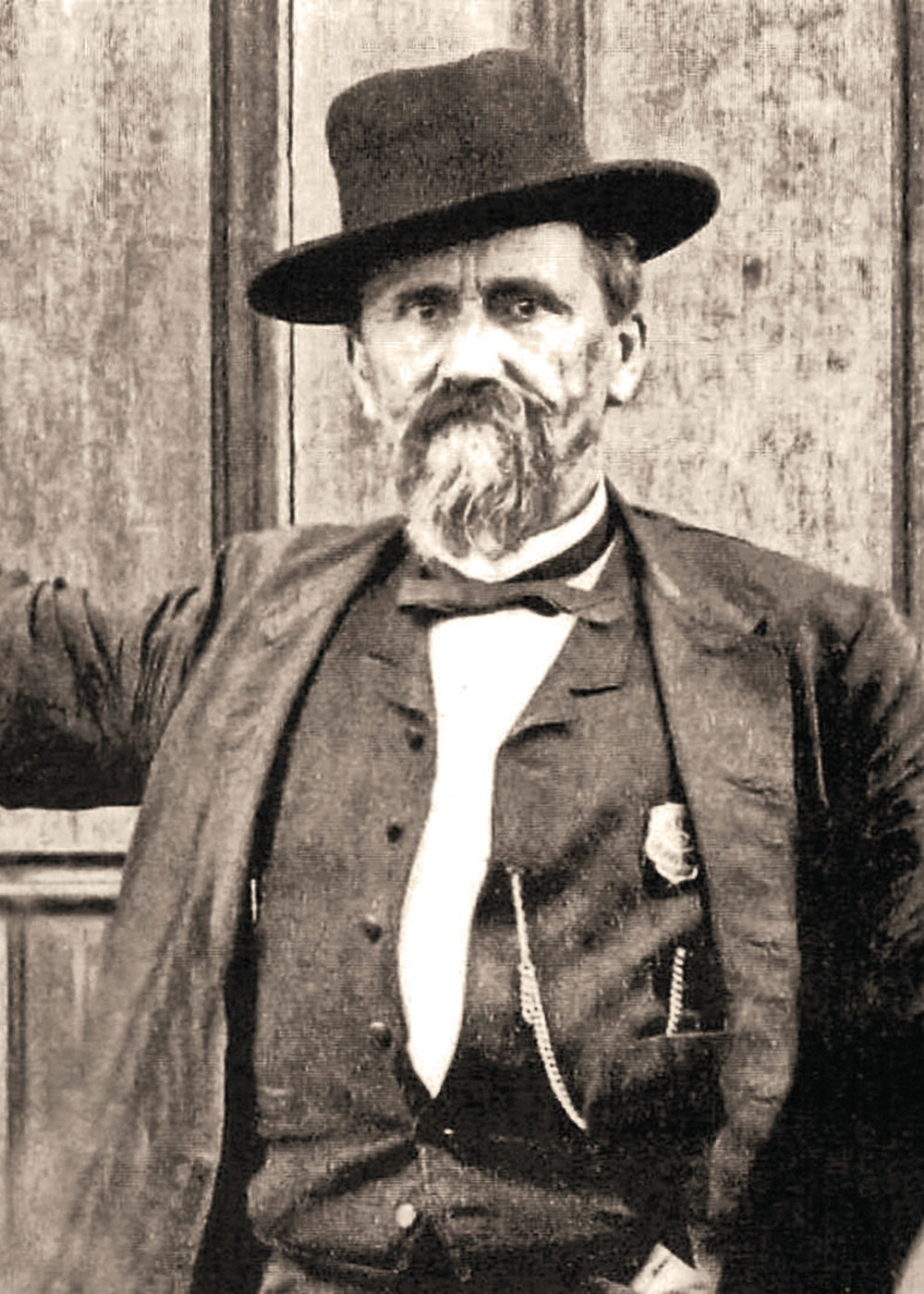

— Courtesy John Boessenecker Collection —

A Man of True Grit

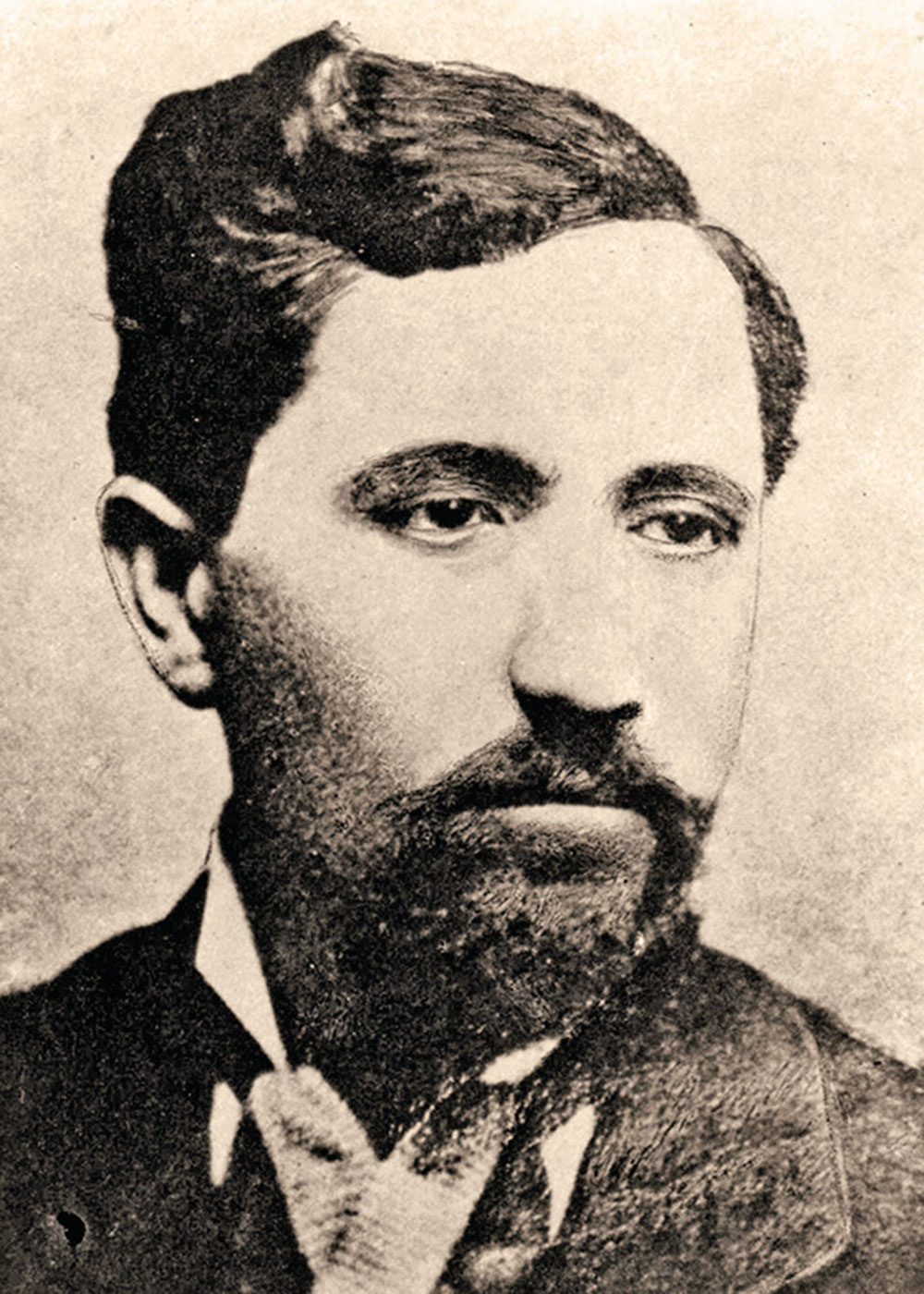

Born in Canada in 1842, Tovey immigrated with his family to the American Midwest when he was six. During the Civil War his twin brother, Peter, enlisted in the Union Army, while Mike drifted west and became a pony rider for Ben Holladay’s Overland Mail & Express Company. This perilous work brought him to the attention of Wells Fargo, and in 1871 he signed on as a shotgun messenger on the bandit-infested stage road from the Union Pacific railhead at Corinne, Utah Territory, to Helena, Montana Territory. Mike Tovey quickly exhibited a fearlessness that matched his powerful physique: he stood more than six feet tall and weighed 200 pounds. As one of his stage driver friends recalled, “Brave men don’t talk much, and Tovey would rather sit and tell you a funny story than blow about himself.”

— Courtesy John Boessenecker Collection —

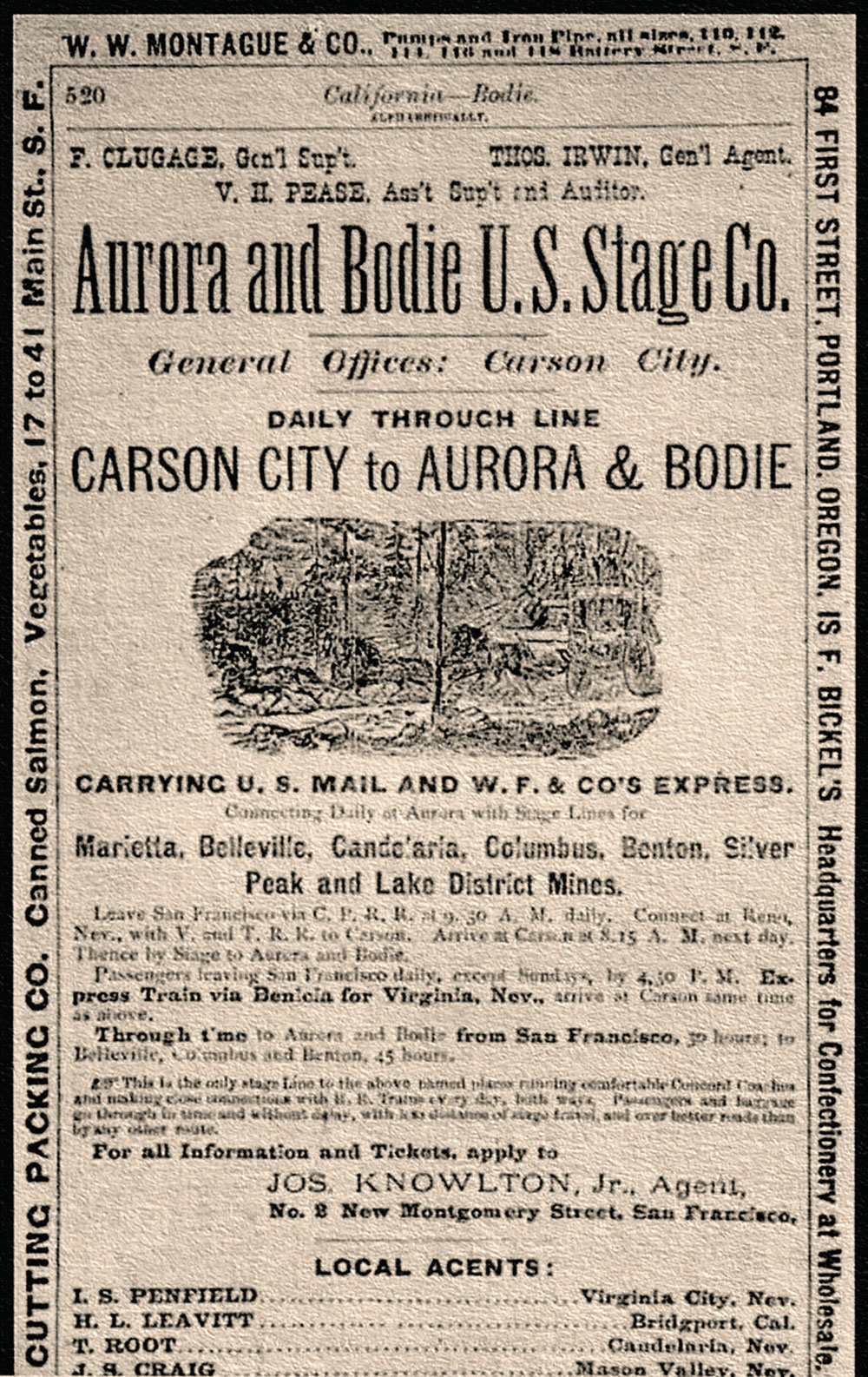

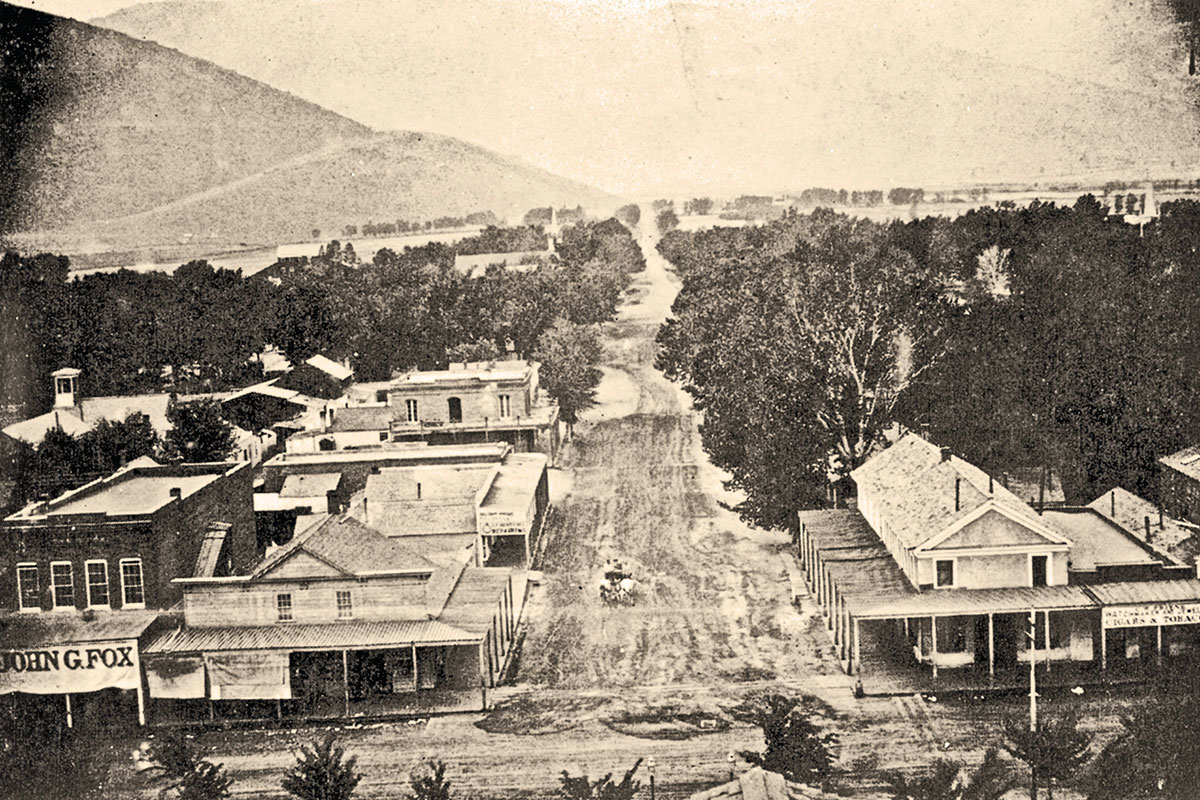

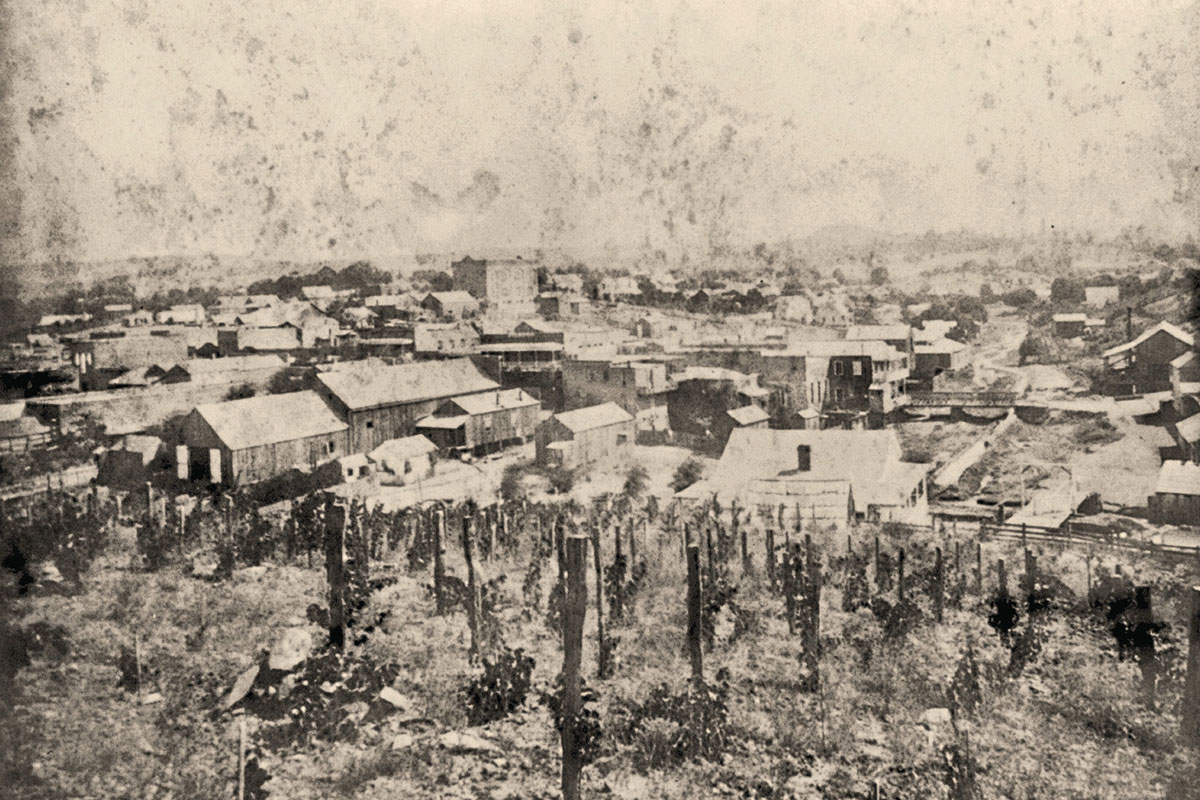

In 1875 Wells Fargo officials sent Tovey to Nevada to guard the company’s express boxes on the stage routes from Virginia City to Pioche, and between Carson City, Nevada, and the rowdy mining town of Bodie, California. Mike was on that route on September 4, 1880, when he found himself walking in front of his stage in the blackness. His flickering lantern lit up the outlines of footprints in the middle of the dusty stage road. Three hours earlier, a coach had been held up on the same highway, and Tovey suspected that the bandits might be lying in wait somewhere ahead of him. He walked back to the stagecoach, climbed onto the driver’s box, and rested his sawed-off shotgun across his knees. If the outlaws wanted a fight, he was ready for them.

— True West Archives —

It was 3:00 a.m. when the heavy stage rumbled into Sweetwater Summit, an isolated spot 6,800 feet high in Nevada’s Sweetwater Mountains, about 40 miles north of Bodie. Once again the alert Wells Fargo man spotted footprints in the light of the coach’s headlamps. He got down with his lantern to inspect them, then climbed aboard. Tovey sat next to the driver, with a stage line agent, H.A. Billings, next to them. There had been so many holdups on the highway between Bodie and Carson City that a second Wells Fargo shotgun messenger, Tom Woodruff, rode inside with the passengers.

— True West Archives —

The stage continued on a short distance when Tovey again saw the bootprints. He swung down and walked forward, inspecting the tracks, as the stage followed slowly behind him. Suddenly a voice rang out from the blackness, “You son of a bitch, you thought you’d sneak up on us, did you?”

Mike Tovey had no way of knowing that the voice belonged to William C. Jones, alias Frank Dow, an ex-convict. He and his partner, Milt Sharp, had been on a terrific spree of stage robbery for the past four months. They had held up seven stagecoaches in California and Nevada, two of them in the last few days. The pair had met the prior winter on a sheep ranch in the Sierra Nevada foothills of Placer County, California. Sharp, born in Missouri in 1846, had led an honest life, coming west in 1866 and working as a miner in California and Nevada. Although he was a gentleman who did not smoke or drink, Sharp had lost all his earnings gambling in risky mining stocks. Jones convinced him they could make a haul by robbing stages.

Now Tovey, hearing Jones’s shout, pretended to be afraid. “Don’t shoot,” he cried. “I’ll go back and get the box.”

“Go back, you whelp, and if you make a move we’ll murder every mother’s son of you,” snarled Jones, who then raised his rifle and fired twice. The first bullet whined by Tovey and struck one of the lead horses in the head, killing the animal instantly. The second passed between the driver and Billings. Tovey dove for cover under the coach, then whispered to Billings, “Hand down that gun.”

Billings tossed him his shotgun and jumped down from the box. Tovey and Billings, joined by Woodruff, took cover behind the stage. At that, Jones yelled, “If you fellows fire a gun, we will murder every son of a bitch of you!”

“Nobody is firing any guns,” Tovey called back, as he cocked the hammers of his shotgun. “What’s the matter with you? If you want anything, come along.”

Jones then stepped forward into the light of the headlamps. Tovey called in a loud voice to the driver, “Throw down the box, quick, and let’s get out of this!”

— True West Archives —

At the same time he crouched and rested the barrel of his shotgun on top of the rear wheel. Just as Jones passed the body of the fallen leader, Tovey fired one barrel. The heavy load of buckshot tore into Jones’s face and neck, killing him instantly. Milt Sharp, armed with a six-shooter, opened fire and Tovey staggered as a bullet tore into his right arm, shattering the bone below the elbow. He dropped his shotgun, drew his six-gun with his left hand, and fired back. By this time Billings and Woodruff got their guns into play and sent a volley of shots toward Sharp. They saw him stagger and thought they hit him. Woodruff chased after Sharp into a stand of willow trees but lost him in the dark and ran back to the stage.

Tovey was bleeding heavily so Woodruff and Billings carried him to a house a short distance down the road, while the unarmed reinsman calmed his team and unhitched the dead horse. Suddenly he heard a voice say, “Throw down the box.” Sharp had returned to finish the robbery. The driver tossed down the Wells Fargo box and Sharp quickly chopped it open with a hatchet and took out $750 in cash. The bandit could not see Jones’s body, because it lay under the team, and asked which way his partner had gone. The driver, fearing for his life, said he didn’t know. Sharp, his gun in one hand and his loot in the other, vanished into the darkness as he continually called out, “Partner, where are you?”

— True West Archives —

Mike Tovey was loaded into a buggy for the jolting, 60-mile trip to Carson City where his wound was treated. Soon he was up and about, his arm heavily bandaged. Meanwhile Wells Fargo detectives searched Jones’s body and found a bank book in his pockets with his name and a San Francisco address. Police detectives staked out the boardinghouse where they soon captured Milt Sharp, who was sentenced to 20 years in the Nevada state prison. Mike Tovey’s action in the holdup had been emblematic of Wells Fargo’s reputation for safety and security on the American frontier.

The Last Ride

Over the years, Tovey was dispatched to wherever Wells Fargo needed an experienced messenger: to Utah, Montana, Arizona, and finally back to Nevada. In 1884, at Hawthorne, Nevada, he was shot and wounded by Bill Withrow, a gunfighter and former Wells Fargo messenger whom Tovey had accused of complicity in a stage holdup.

In 1887 Mike Tovey was ordered to California where he rode the stage routes of Amador and Calaveras counties in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Two years later Milt Sharp fled the Nevada state prison. Following his escape, Wells Fargo officials received a letter, purportedly written by Sharp, warning them to retire Tovey or he would be killed. Later Tovey received a letter, again signed by Sharp, warning him to leave California or “take the same medicine dealt out to poor Jones.” The veteran messenger ignored the threats.

Then, at seven o’clock on the morning of April 30, 1892, he boarded a stage in San Andreas, bound for Sheep Ranch, in the mountains 16 miles to the east. The Wells Fargo box held a mine payroll of $4,000 in gold coin. The coach was a canvas-topped “mud wagon,” like a huge buggy, with three seats. The front seat held Tovey and the driver, 17-year-old Alphonso “Babe” Raggio. The second seat was occupied by Johannah Rodesino, age 15, and her sister, Louisa, 14. The rear seat held two more female passengers.

As the coach reached Willow Creek, a masked bandit arose from behind a large boulder above the stage road. Without a word of warning, he fired a single blast from his shotgun. Two buckshot struck young Raggio in the right shoulder and two more in his breast, piercing his right lung. He reeled in his seat, and as blood poured from his mouth, gasped, “They have killed me, Tovey, look out for the horses.”

At the same time another buckshot tore into Mike’s right arm and several more struck Johannah Rodesino in the chest and head, killing her. A huge manhunt failed to capture the killer, and Tovey and Raggio recovered from their wounds. In May 1893 Mike received another letter signed “Sharp” saying that he “had better leave Wells Fargo service and get out of the state, otherwise he would apt to be killed.” A few weeks later, on the afternoon of June 15, 1893, he boarded the stage in Ione, bound for Jackson. At the reins of the six-horse team was Tovey’s good friend, Clint Radcliff, a veteran driver. Inside the coach were four passengers, including two women and a boy, and a fifth rode on top with the driver and messenger.

It was 5:30 when the stage reached a lonely spot on the Morrow grade, five miles west of Jackson. Several of the passengers heard a sudden shout for the stage to halt, but Radcliff made out nothing over the rumbling of his coach. A split second later gunfire shattered the evening stillness. A lone bandit stood behind a three-foot high rock pasture fence on the right side of the road, working the lever of his .44 Winchester rifle. His first bullet struck Mike Tovey in the ride side, fracturing one rib and rupturing his aorta. The Wells Fargo man started to fall from the stage, and Radcliff yanked him upright. By the time Radcliff managed to halt the coach 300 yards down the road, Mike Tovey was dead.

— True West Archives —

Milt Sharp was captured in Red Bluff, in northern California, three months later. He managed to prove that he had led an honest life since his escape, and provided alibis from his employers showing that he could not have been at the murder scene. Wells Fargo’s chief detective, Jim Hume, believed Sharp and helped get him a parole in 1894. An ex-convict, William Evans, was charged with killing Mike Tovey. A jury convicted Evans of first-degree murder and he was sentenced to life in San Quentin.

— Courtesy John Boessenecker Collection —

Mike Tovey was laid to rest in Jackson’s city cemetery. Wells Fargo paid for his marker, which read, “He was shot and instantly killed by a robber who attempted to hold up the stage on which he was traveling as guard. Erected as a tribute of respect by his employers.” He remains one of the most famous of the men who rode for Wells Fargo.

— Courtesy John Boessenecker Collection —

“Shotguns and Outlaws: Well’s Fargo Shotgun Messenger Mike Tovey was one of the bravest of them all” is excerpted from John Boessenecker’s book, Shotguns and Stagecoaches: The Brave Men Who Rode for Wells Fargo in the Wild West.