At the age of sixteen, Carson ran away from his job as an apprentice at a saddlery in Missouri and joined a party of traders heading down the Santa Fe Trail. By 1831, under the tutelage of the famed mountain man, Ewing Young, Carson was a first-class free trapper with a reputation among his fellow trappers for trustworthiness, courage and honesty.

At the rendezvous on the Green River in 1835 he fought a famous duel with a French Canadian named Chouinard who got loaded on whiskey and began challenging all comers to fight. After the Frenchman beat up two or three bragged that he’d take a switch to Americans and beat them like children. Carson had been quietly taking it all in. “I did not like such talk from any man.” he said later to the author writing his biography, “so I told him that if he made use of anymore such expressions, I would rip his guts.”

Without further words both men went for their horses. Chouinard grabbed his rifle and Carson went for his pistol. Carson said he “galloped up to him and demanded if I was the one which he intended to shoot. He said no but at the same time drawing his gun so he could have a fair shot. I was prepared and allowed him to draw his gun. We both fired at the same time……I shot him through the arm and his ball passed my head, cutting my hair and the powder burning my eye, the muzzle of his gun being near my head when he fired. During our stay in camp we had no more bother with this bully Frenchman.”

Carson also knew when to retreat from a fight. One evening he was hunting supper for his fellow trappers when he shot an elk. About that time two grizzlies charged him from the brush. His rifle was unloaded so he had to make a run for it. He headed for some trees with the bears hot on his tail. He climbed up one of them hoping they’d soon lose interest. One did but the other kept him treed for several hours.

In 1842 made the acquaintance of John C. Fremont, a young army lieutenant with the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, who was about to leave on an expedition to map and explore the Rocky Mountain West. Fremont would eventually go down in American history as “The Great Pathfinder,” but at the moment he was just another ambitious soldier. He was also the son-in-law of the powerful U.S. Senator from Missouri, Thomas Hart Benton.

Fremont was looking for a guide and Carson modestly admitted he had, “been some time in the mountains.” After checking out his credentials Fremont hired him and on that first expedition, they would map what would become the storied Oregon Trail. It was a fortuitous chance meeting for Kit Carson. Had there been no John C. Fremont there might never have been a Kit Carson and visa-versa.

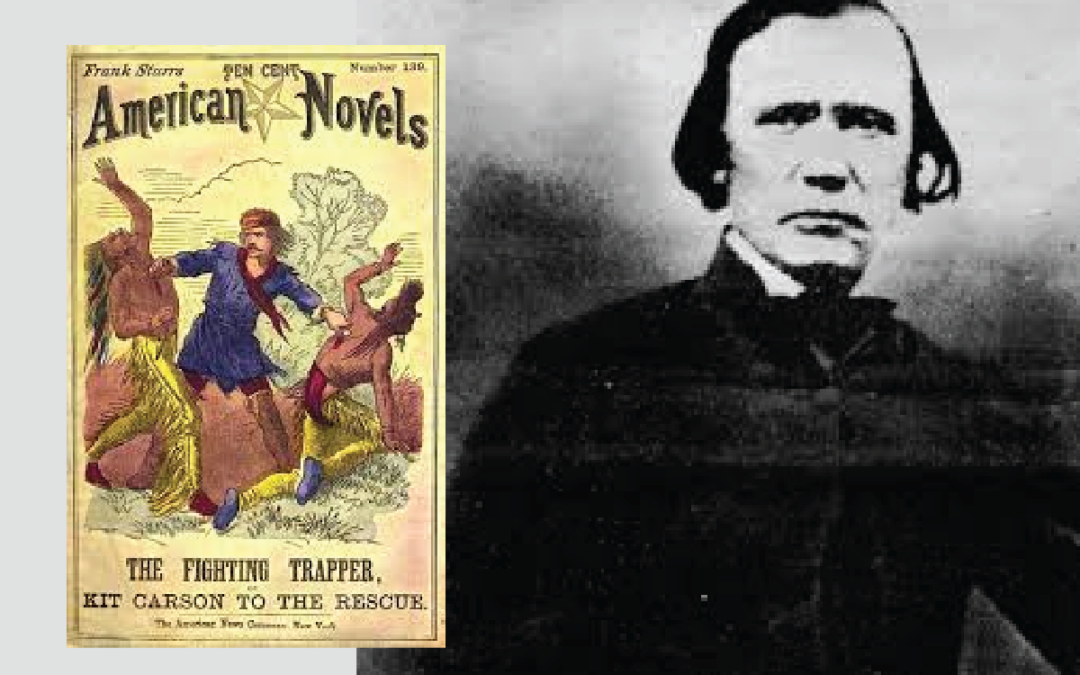

Fremont’s stories about his heroic feats also brought national attention in the wrong places. Some seventy pulp novels featured Carson, without compensation nor his permission. Sensationalized stories portrayed him as a blood and guts, rip-snorting, giant of a man who slaughtered Indians by the dozen. There wasn’t a grain of truth in the action-packed thrillers, but easterners devoured them.

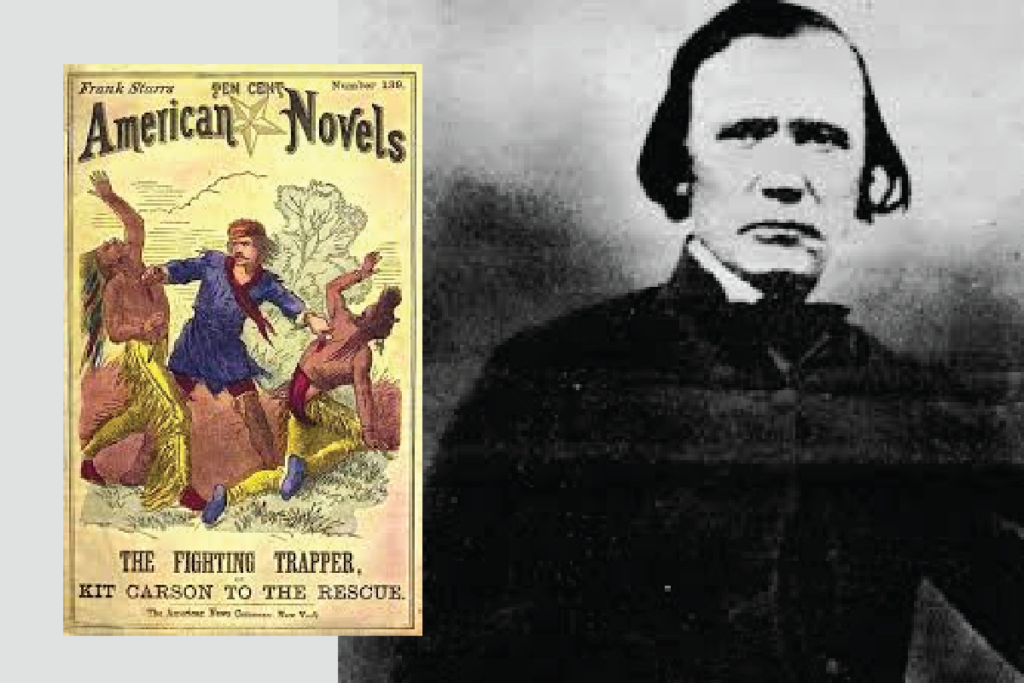

Had they met the real Kit Carson they would surely have been disappointed as was a young Army officer named William Tecumseh Sherman.

This so-called fire-eating giant of a man stood only 5’5 ½ inches, weighed just 140 lbs. and was illiterate. His quiet, unassuming manner, stoop shoulders, short stature and gentle voice did nothing to reveal the dauntless courage he possessed.

Charles Averill’s pulp fiction, “Kit Carson, Prince of the Gold Hunters,” depicted him as a mass killer of Indians and credited him as “the man who discovered gold in California.” On another pulp he was shown on horseback holding a beautiful, scantly-clad captive woman that he rescued with one hand while fighting off Indians with the other. When it was shown to him he glanced at it and modestly replied, “That thar may be true but I hain’t got no have no recollection of it.”