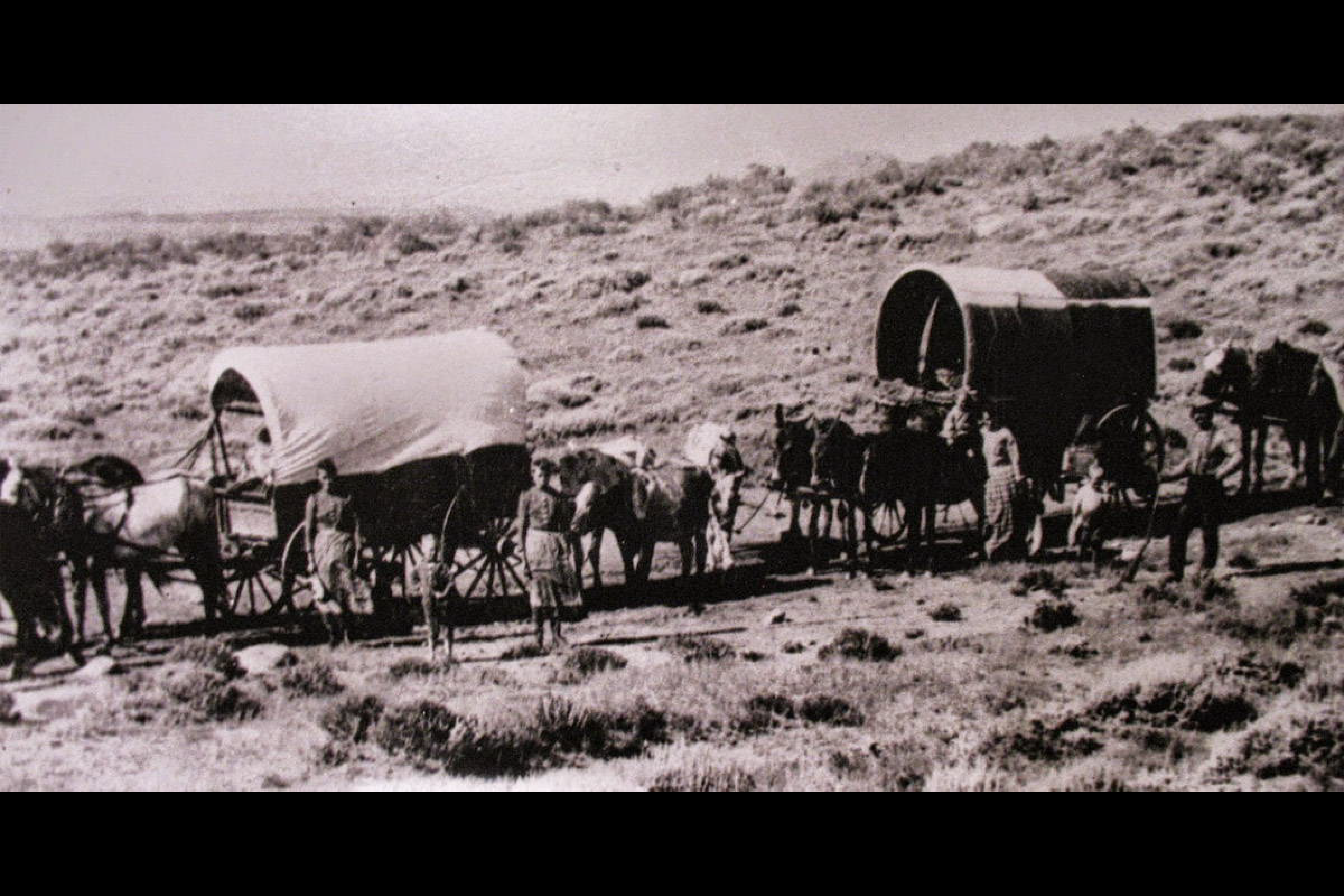

Most wagons were about six feet wide and twelve feet long. They were usually made of seasoned hardwood and covered with a large, oiled canvas stretched over wood frames. In addition to food supplies, the wagons were laden with water barrels, tar buckets and extra wheels and axles.

The sturdy prairie schooners could carry up to 2,500 pounds. Most of the space was taken up by 1,800 pounds of food.

The Amerinds were more often kind than warlike. They helped at dangerous river crossings. Only about 300 pioneers died from Indian attacks between 1840 and 1860.

Wagon trains didn’t want to leave too early or too late. April or May if they hoped to reach Oregon before the winter snows began. Leaving in late spring also ensured there’d be ample grass along the way to feed livestock.

While most Oregon-bound emigrants traveled a route that passed by landmarks in Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho and Oregon, there was never just one set of wagon ruts leading west. Pioneers often spread out for several miles across the plains to hunt, find grazing patches for their animals and avoid the choking dust clouds kicked up by other wagon trains. As the years passed, enterprising settlers also blazed dozens of new trails, or cutoffs, that allowed travelers to bypass stopping points and reach their destination quicker. These shortcuts were especially popular in Wyoming, where the network of alternative pathways meandered more than a hundred miles north and south averaging between ten and fifteen miles per day.

In 1860, a man named Samuel Peppard attached a canvas sail to a wagon and sailed across the breezy plains of Nebraska, reaching speeds of up to 40mph. Unfortunately, Peppard’s wind wagon met its demise when he ran into a small tornado outside Denver.

From Fort Kearney, they followed the Platte River over 600 miles to Fort Laramie and then ascended the Rocky Mountains where they faced hot days and cold nights. Summer thunderstorms were common and made traveling slow and treacherous.

At the most dangerous river crossing, on the North Platte River near Casper, Wyoming,

The settlers gave a sigh of relief if they reached Independence Rock—a huge granite rock that marked the halfway point of their journey—by July 4 because it meant they were on schedule. So many people added their name to the rock it became known as the “Great Register of the Desert.”

After leaving Independence Rock, settlers climbed the Rocky Mountains to the South Pass. Then they crossed the desert to Fort Hall, the second trading post.

From there they navigated Snake River Canyon and a steep, dangerous climb over the Blue Mountains before moving along the Columbia River to the settlement of Dalles and finally to Oregon City. Some people continued south into California.

Some settlers looked at the Oregon Trail with an idealistic eye, but it was anything but romantic. According to the Oregon California Trails Association, almost one in ten who embarked on the trail didn’t survive.

Most people died of diseases such as dysentery, cholera, smallpox or flu, or in accidents caused by inexperience, exhaustion and carelessness. It was not uncommon for people to be crushed beneath wagon wheels or accidentally shot to death, and many people drowned during perilous river crossings.

Travelers often left warning messages to those journeying behind them if there was an outbreak of disease, bad water or hostile American Indian tribes nearby. As more and more settlers headed west, the Oregon Trail became a well-beaten path and an abandoned junkyard of surrendered possessions. It also became a graveyard for tens of thousands of pioneer men, women and children and countless livestock.

The first major wagon train of around 1,000 settlers along the Oregon Trail, an exodus now known as the “Great Migration.” Traffic soon skyrocketed, and by the late-1840s and early 1850s, upwards of 50,000 people were using the trail each year.

Popular depictions of the Oregon Trail often include trains of boat-shaped Conestoga wagons bouncing along the prairie. But while the Conestoga was an indispensable part of trade and travel in the East, it was far too large and unwieldy to survive the rugged terrain of the frontier. Most pioneers instead tackled the trail in more diminutive wagons that become known as “prairie schooners” for the way their canvas covers resembled a ship’s sail. These vehicles typically included a wooden bed about four feet wide and ten feet long. When pulled by teams of oxen or mules, they could creak their way toward Oregon Country at a pace of around 15 to 20 miles a day. They could even be caulked with tar and floated across un-fordable rivers and streams. Prairie schooners were capable of carrying over a ton of cargo and passengers, but their small beds and lack of a suspension made for a notoriously bumpy ride. With this in mind, settlers typically preferred to ride horses or walk alongside their wagons on foot.