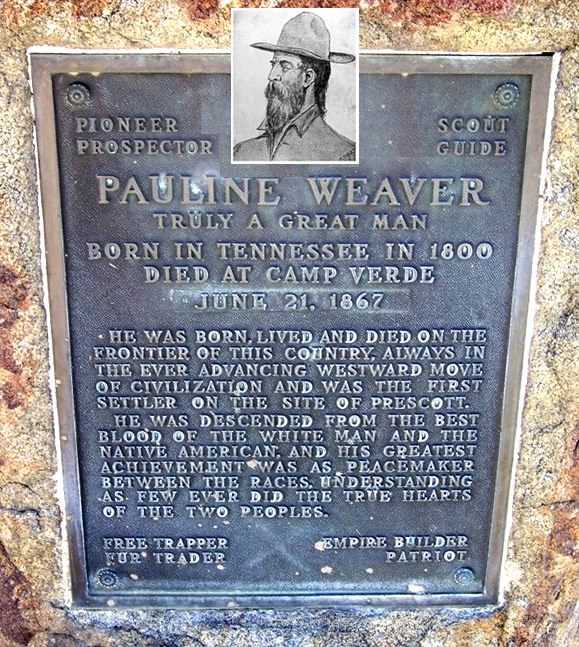

Another Mountain Man who left his mark on the Southwest was Paulino Weaver. He was born Powell Weaver in White County, Tennessee, the son of a German father and a Cherokee mother in 1797. As a young man he worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company as a trapper. In 1830 he went west to the Rocky Mountain with a band of fur trappers, winding up in Taos, New Mexico. It was at Taos that he dropped the name Powell and adopted the Spanish Paulino. Later it was changed to the English Pauline.

Although he was only half-Indian, he was always more comfortable in the Indian cultures than the white. He was one of, if not the first half white man to settle in Arizona. He knew the rivers, mountains and trails better than any other white man. In 1832, somebody scratched his name on the walls of the prehistoric Casa Grande Ruin near the Gila River. Since Weaver made his mark with an “X” until his dying day, the signature is but one more mystery at that site.

During the Mexican War he acted as a guide for the storied Mormon Battalion on their historical trek building a wagon road across Arizona to California.

In 1862 some natives along the Colorado River in western Arizona showed him some rich gold placers at La Paz, not far from today’s Ehrenberg. Before the gold played out, some 12 million dollars’ worth of the yellow metal had been panned out.

The boom town of La Paz that sprang up nearby almost became the capital city of the new Territory of Arizona. Then one day capricious Colorado River changed its muddy course and left La Paz, along with a couple of steamboats high and dry in the desert. The town picked up and moved over to the river re-naming itself Ehrenberg after the German prospector-engineer Herman Ehrenberg who had been recently killed by Indians in California.

The same year Weaver discovered gold at La Paz, he hired out as Chief of Scouts for the California Volunteers. A small force of Confederates from Texas had occupied Tucson earlier that year and were probing their way along the Gila River towards the strategic river crossing at Yuma where the Gila and Colorado rivers meet. The Reb’s retreated back up the Gila in the face of the 2,300-man force of Union volunteers.

On April 15, 1862, remnants from the two sides met at Picacho Peak where a small battle was fought. Although the Confederates won the fight the realized they couldn’t engage such a large force of Yanks so they began their long retreat back to Texas. The battle is recognized as the westernmost battle of the Civil War.

Weaver then resumed his life as a prospector and guide. Not long after the Walker party found gold in the Bradshaw Mountains, in 1863, Weaver guided the Abraham H. Peeples party up the Hassayampa River in search of another madre del oro. A few miles north of the future town of Wickenburg they stumbled upon a treasure trove of gold nuggets lying atop a rocky knoll that was rightfully named Rich Hill. Within five years, a half-million dollars in placer gold was mined. It was the richest single placer strike in Arizona history and how it got deposited on top of a hill is still an enigma, but gold, as they say, is where you find it.

During those first months, following the gold strikes Weaver worked tirelessly to negotiate a treaty between the native tribes and newcomers and succeeded for a spell. The Indians used the password “Paulino-Tobacco,” which was to indicate to the whites they were friendly. Tobacco was a word nearly every Indian knew and understood as it was always given by whites during a parley as a token of friendship. As more whites poured in who weren’t aware, or didn’t care about the arrangement, the treaty became meaningless. Too many cultural differences and mutual mistrust caused the inevitable outbreak of hostilities.

In the mid-1860s, Weaver himself was jumped by a war party outside Prescott and seriously wounded. The old scout thought he was a goner and went into his “death song”—a custom he’d adopted from the Plains Indians. The suspicious warriors, not familiar with the ritual, believed he’d gone crazy and scattered and when Weaver saw he wasn’t going to die, he got up and casually walked home. The wound did, however, continue to trouble him for the remainder of his days.

It is said the natives were remorseful about shooting Weaver and during friendly parleys always asked how “Powlino” was getting along.

When the first settlers moved into the Verde Valley, the army was called in to provide protection from a growing number of attacks. The officers wisely brought Weaver in to bring about a peace treaty. His service, according to military records, was invaluable but ol’ Dad Time was catching up. His health deteriorated and, on June 21st, 1867, Pauline Weaver died. He was buried at Camp Verde (Lincoln) with full military honors. Later, when the post was abandoned, his remains were taken to California.

In 1929, poet-historian Sharlot Hall organized a campaign to have Weaver’s remains returned to Prescott. Thanks to the Boy Scouts and Prescott school children, funds were raised and Weaver was re-buried on the grounds of the old Territorial capitol. Territorial Historian Hall declared him Prescott’s First Citizen—a title he richly deserved.