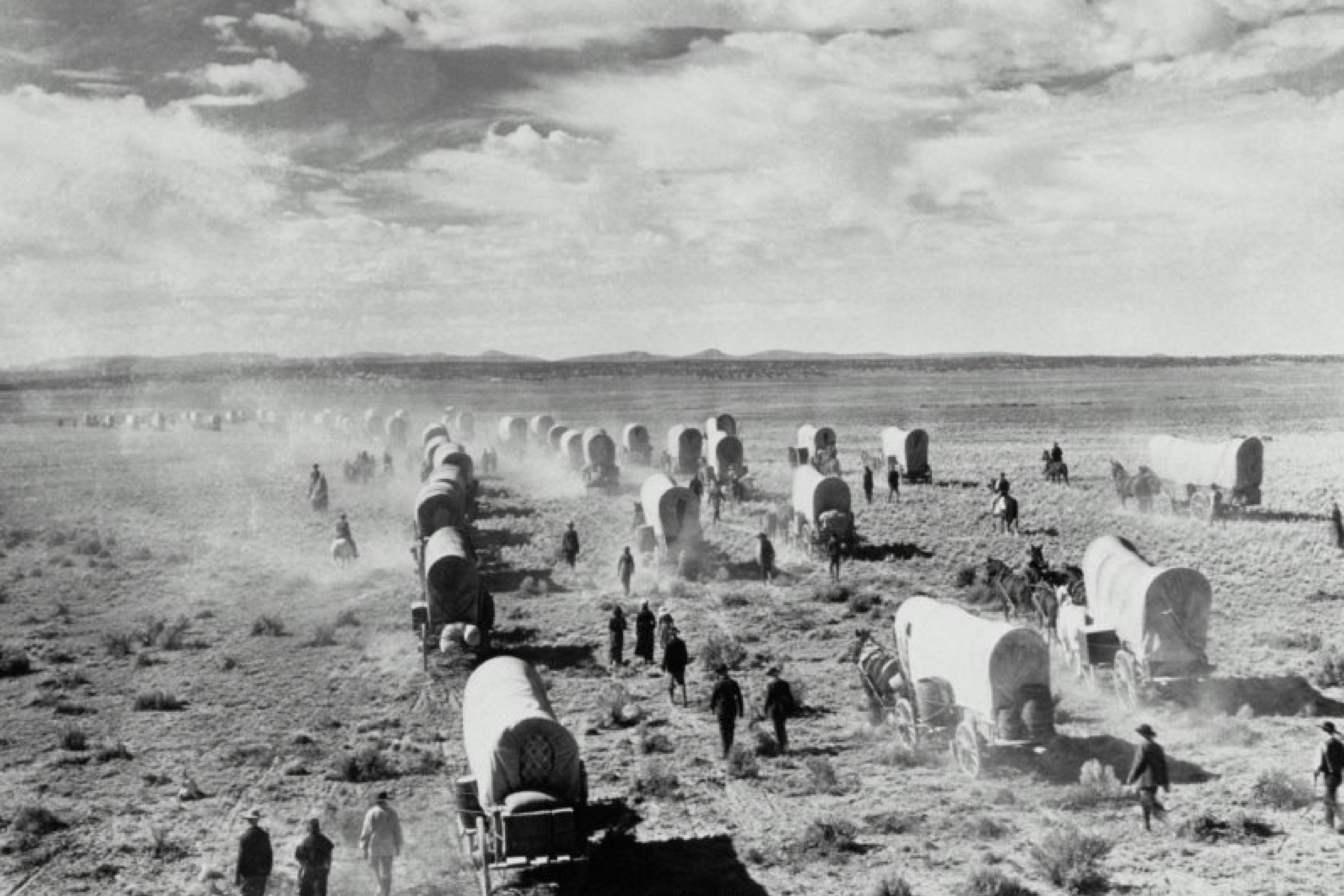

Before the days of railroad dining cars, passengers were forced to eat in the local hash houses wherever the train happened to stop. The food was terrible and the service was even worse. The passengers would rush in, place an order and just about the time the food arrived, the conductor called out “All Aboard.”

Meal tickets were sold to the passengers by the conductor prior to stopping and he received a kickback from the restaurant when the meal was not eaten. The same meal could be sold more than once and probably was.

Not only were conditions deplorable for train passengers but they were even worse for single men in the cities and towns. They were at the mercy of the local restaurants and hotels where the basic tool was the frying pan and it was the cause for much dyspepsia among the populace.

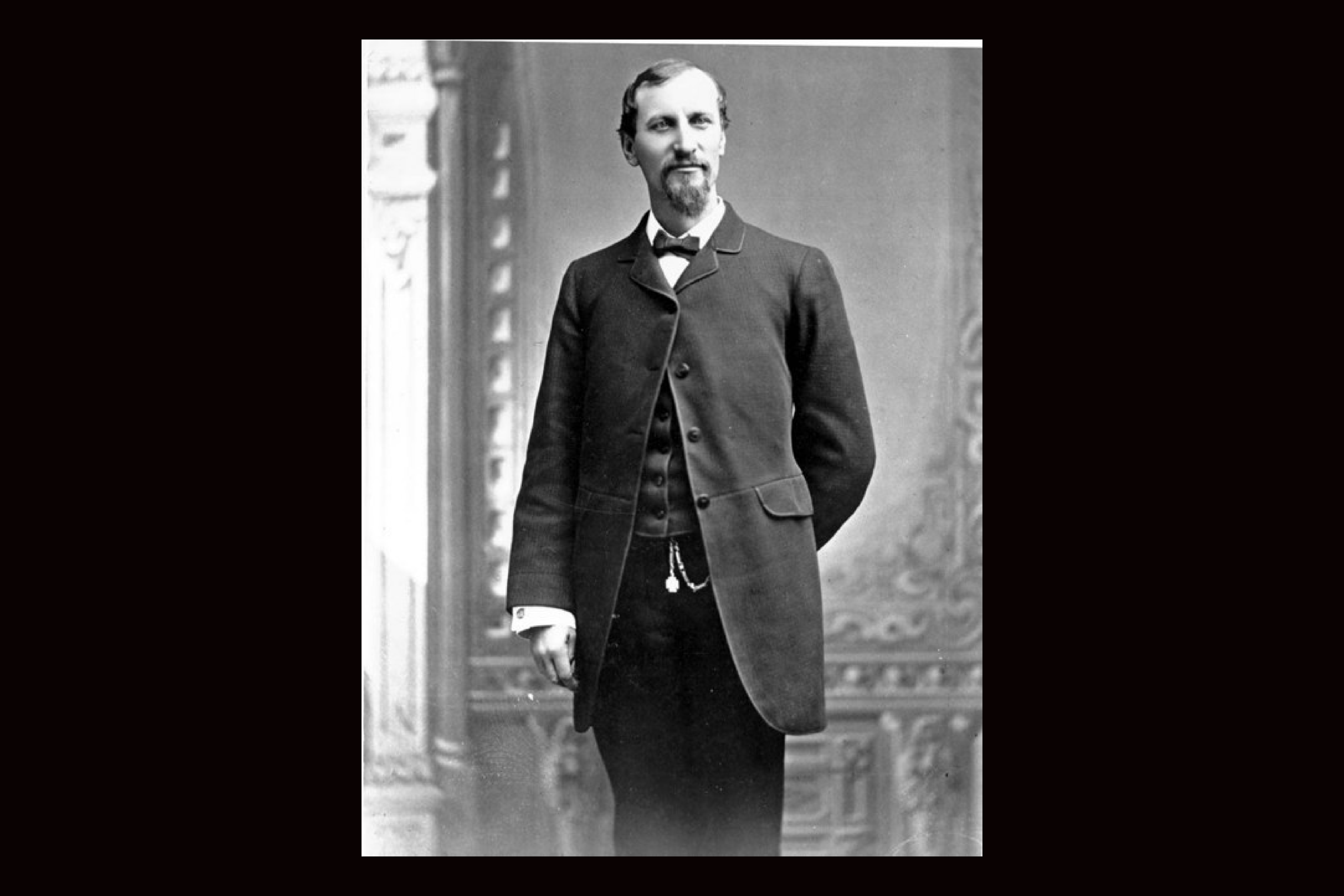

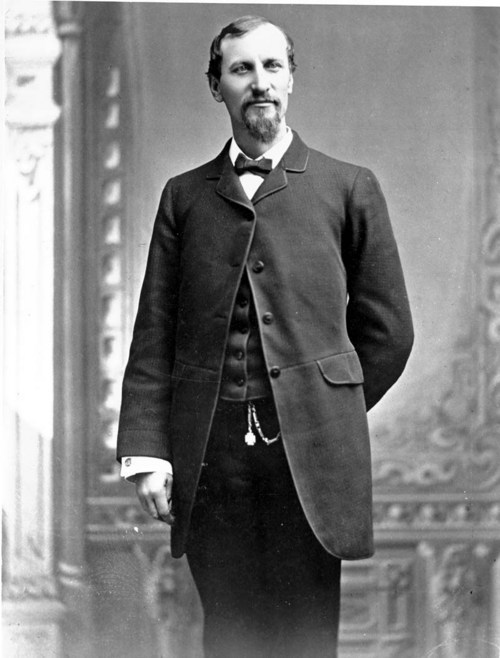

It took an Englishman named Fred Harvey to bring real cuisine to the American Southwest. After experiencing some of the eating conditions along the rail lines, Harvey approached the Santa Fe Railroad in the early 1870s with the sagacious idea of providing passengers with attractive surroundings, superior service and above all, good food. The railroad company accepted his proposal enthusiastically, for food services had been one of the most serious problems plaguing all the railroads at the time. The Santa Fe agreed to build and supply all the buildings, along with the transporting of food, furnishings and personnel, free of charge. In addition Harvey was to receive all profits from the venture. Evidently the Englishman was not only a good restauranteur, but a shrewd bargainer as well.

The first Harvey House opened for business at Topeka, Kansas in the spring of 1876 and was an immediate success. French chefs were hired away from prominent restaurants in the East and paid handsome salaries. In at least one instance the Harvey House chef was making more money than the president of the local bank.

As trains pulled into the hotels and restaurants he established, his crew had from twenty to thirty minutes to feed sixty to one hundred people. Yikes! To accomplish that, the Harvey Houses had a streamlined system to be certain everyone got their dinners in time. When patrons sat, the first question was which beverage they preferred, and then, as if by magic, another waitress came by and delivered their drinks. It was all in the cups! The Harvey Girl who took the drink order assured they’d get the proper beverage by how she positioned the cups. A cup upright in the saucer meant coffee. Cup upside down in the saucer meant hot tea. A cup upside down, tilted against the saucer meant iced tea. A cup upside down, away from the saucer meant milk. Ingenuous. And it worked.

Breakfast included cereal, fruit, eggs atop a steak, hash browns, and six large hot cakes with butter and maple syrup, topped off with apple pie and coffee: 50 cents

Dinners cost a quarter more and included a fancy gourmet dish or wild game.

During the next twenty years Fred Harvey opened his elegant Spanish-style restaurant-hotels at one-hundred-mile intervals along the Santa Fe Railroad line. It was said they were spaced that distance so they would keep western flow of traffic from settling in one place where Harvey served his meals.