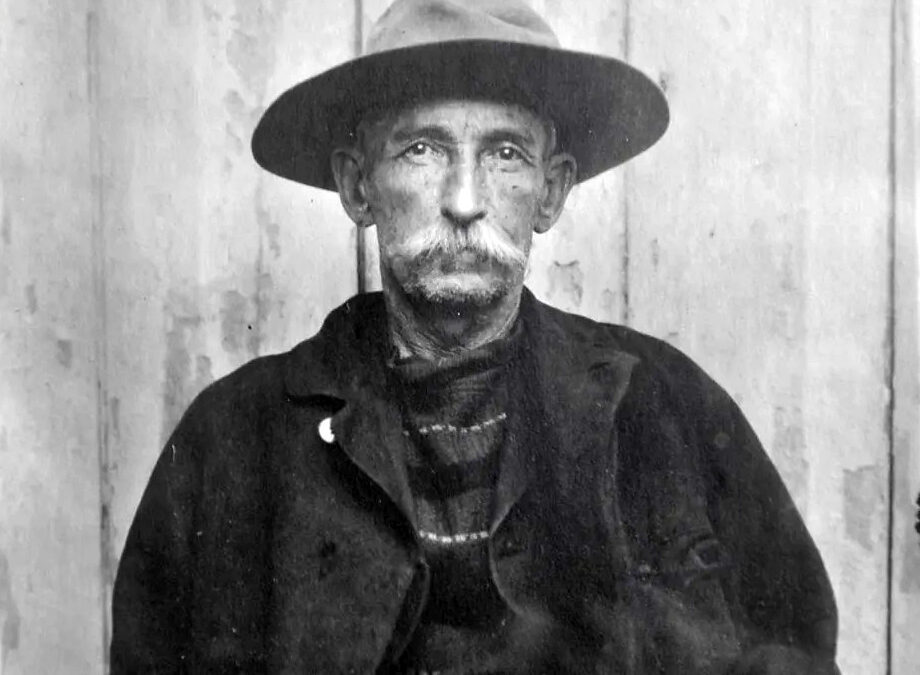

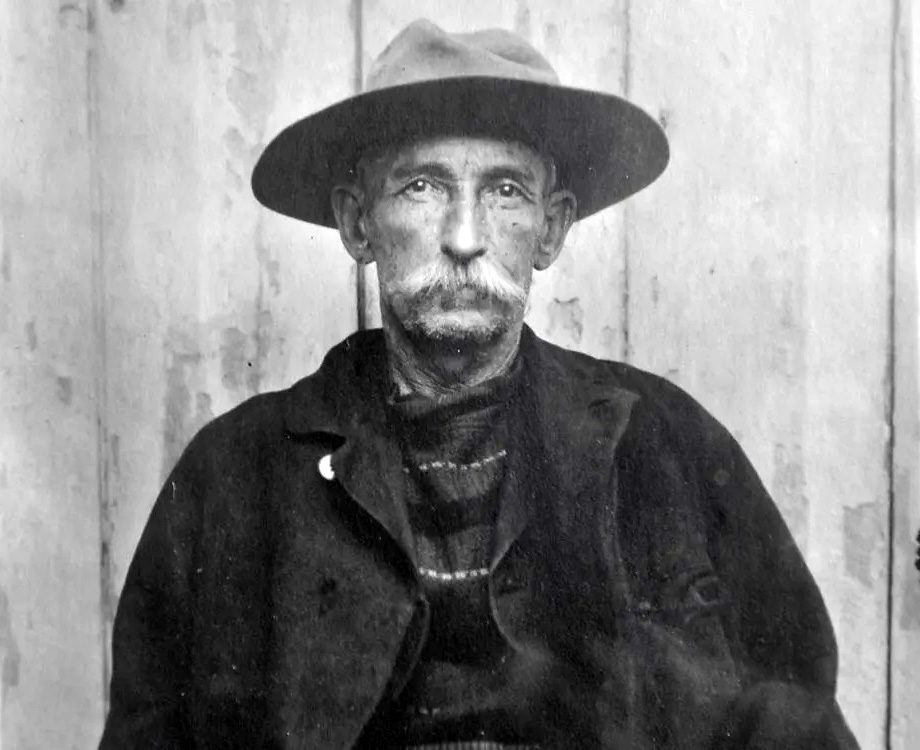

Ezra Allen Miner is a conundrum. Some say he was born in Onondaga, Michigan on December 27th, 1846, or maybe he was born in Bowling Green, Kentucky. Apparently, Miner didn’t like the name Ezra but he never bothered to change it legally, he just decided that henceforth his first name was going to be Bill.

In 1860, following the death of his father, the family moved to Placer County California. Six years later, at the age of twenty he was arrested for the first time, convicted of horse theft, and spent the next four years at San Quentin.

Six months after his release, Bill and a few friends pilfered a Wells Fargo strongbox from a stagecoach. He and “Alkali Jim” Harrington were captured and tried in Calaveras County. They appealed their 10-year sentence because they’d been forced to wear leg irons. Their protest earned them a new trial but a worse sentence of 13 years in the pen.

Released in 1880, Bill went to Colorado and joined up with the Pond brothers as a stagecoach robber. A posse caught up with them, but Bill got away. The unlucky brothers were given suspended sentences—from the limb of a nearby tree.

Over the next thirty-five years he spent twenty-nine years and seven months behind bars. He was released twice and escaped five times. Wm. Pinkerton of the famous detective agency would refer to him as the “master criminal of the American West.”

He partnered with Bill Leroy and robbed a stagecoach. Leroy was caught and lynched but Miner managed to get away. He robbed another stage in Tuolumne County in California’s Mother Lode country. The long arm of the law caught up with Bill….again and he was given a twenty-five-year sentence for stagecoach robbery. He tried to break out in 1892 and all he got for his trouble was a neck full of buckshot. He was released on June 17th, 1901.

Bill walked out of the gate at San Quentin to find the world had changed dramatically. Stagecoach robbery was a thing of the past and if he was going to resume his career as a highwayman, he would have to alter his modus operandi. Trains carried now the express money. It was going to take more than standing in the middle of the road and shouting, “Hands Up!”

Oklahoma’s Al Jennings had already shown it wasn’t smart to stand on the tracks waving a pistol at a locomotive and expect the engineer to put on the brakes. He didn’t and the clueless wannabe train robber jumped out of the way just in time.

On September 19th, 1903, at the age of fifty-four, Miner made his first attempt at train robbery and fared about as well as Jennings. He and two confederates, Guy Harshman, an acquaintance from San Quentin and 17-year-old Charlie “Kid” Hoehn attempted to hold up a passenger train a few miles east of Portland, Oregon. The train sped on by leaving them standing there high and dry. They’d set the “Stop” signal on the wrong set of tracks.

Two days later, just a few miles from their previous attempt they tried again. While attempting to blow the doors off the express car, one of the messengers inside opened up with a sawed-off shotgun. Harshman was shot in the head and captured while Miner and the kid fled. Their getaway vehicle was a rowboat tied up at the Columbia River. They jumped in and rowed frantically to the Washington side where they split up.

Harshman survived and gave up his two cronies. Boehn was caught and fingered Miner. Bill gave lawmen the slip again and with the help of his former cellmate at San Quentin, Cowboy Jake Terry, he was smuggled into Canada.

Jake Terry began his notorious career as a smuggler while working as a railroad engineer, something that cost him a couple of stints in the federal prison. He hired out as a policeman before joining a group of counterfeiters in the Seattle and wound up back in prison where he became Bill Miner’s cellmate. Because of his violent personality he was also known as “Terrible Terry.” Although Miner and Terry ware the exact opposites in temperament and personality they were a perfect match. Terry, thanks to his experience with the trains, tapping telegraph lines, schedules and timetables he would play a major role in the planning and executing of Canada’s most sensational train robbery.

On September 10th, 1904, during a heavy fog, Miner, Terry and Shorty Dunn, another man recruited by Miner, sneaked aboard the Canadian Pacific Railroad’s Transcontinental Express at Mission Junction, British Columbia.

Terry knew that customarily, the safe was locked between stations so earlier that day he tapped into the wires and posing as an official at headquarters ordered the agent at Mission Junction to leave the safe unlocked. Now the boys would have easy entry to the plunder inside.

One of the safes turned out to be empty but the other held six thousand dollars in gold dust and one thousand dollars in cash.

Miner loaded some fifty thousand dollars in U.S. Government bonds and an estimated quarter of a million dollars in negotiable Australian securities. The robbery took just thirty minutes. After a few parting words the three train robbers disappeared into the foggy darkness.

Believing the bonds and securities were too easy to trace and impossible to fence, he hid them. They were never found.

In between jobs Miner posed as a genial, wealthy cattle buyer named George Edwards and in effect, the crafty train robber was hiding in plain sight.

Normally gold was carried in safes in the express car that was hitched next to the engine. The robbers would sneak into the coal tender as the train was leaving the station. After they’d gone a few miles they would drop down into the cab, force the engineer to stop the train, unhook the baggage car and passenger cars. They’d order the engineer to take the train further down the tracks so they could break into the express car without any interference from the passengers or crew. In order to confuse train robbers, the baggage and express cars were sometimes reversed.

Jake Terry missed out on Miner’s next caper. By chance he ran into his ex-wife, who had re-married, sweet-talked her into bed, then tossed her new husband out of the house and moved in with her. He commenced to terrorize the town of Sumas for a whole week before getting tossed in jail. He was arrested and jailed causing him to miss the ill-fated train robbery.

On May 8th, 1906, turned out to be a fiasco. Between Kamloops and Ducks (now Monte Creek) British Columbia, Miner, along with Shorty and Louis Colquhoun attempted to rob the Canadian Pacific Railroad a second time. Unwittingly they uncoupled the express car that was carrying $80,000 in gold and broke into the baggage car instead. Miner shook his head in disgust and that only made matters worse as his mask slipping giving the mail clerk a good look at him. In his haste he failed to see several packages containing some $40,000 in banknotes. Their take on the job was fifteen dollars and some change. The next day, in their haste to elude a posse the trio ran off leaving their pack horses and provisions behind.

Captured by the Mounties and Indian trackers several days later, about 80 miles south of Ducks, the three train robbers were taken to Kamloops to stand trial. Newspapers carried the story and the headlines read: “Leader of Gang Is Identified as Old Bill Miner.” In spite of his blunders Bill had become a famous outlaw.

Bill’s dealings with his old cellmate, Jake Terry aka “Terrible Terry” ended on July 5th, 1907 when a jealous husband caught him sleeping with his wife and shot him dead.

Miner was now sixty years old and seemingly feeble. The daughter of the deputy warden took pity on him and was convinced she could reform the wily grey fox of his wicked ways through religious teachings. Bill went along with it and soon was allowed to work outside the prison walls. On August 8th, he and two others managed to tunnel under a board fence, take a ladder, scale the outer wall and make their getaway. Bill took off and ran all the way to Pennsylvania.

In 1911 he robbed another train in Georgia. Bill seemed to excel at getting caught. He was captured and given twenty years in the state pen. He escaped twice and was caught easily both times. While hiding in a Georgia swamp he contracted gastritis from drinking brackish water. He opined casually to the guards who captured him, “I guess I’m getting too old for this sort of thing.”

Throughout his life and even in the afterlife Bill succeeded in eluding those who sought to track down the real story. He had the uncanny ability to charm everyone who came in contact with him including his robbery victims, prison guards, lawmen and fellow outlaws. He habitually lied and mislead his listeners, especially the journalists who interviewed him late in life. In the end he came to believe the whoopers he told on himself.

He died in prison on September 2nd, 1913, at the age of sixty seven. Nobody claimed his body, so Bill was buried in the city cemetery at Milledgeville, Georgia.

It was discovered later that Bill’s tombstone was in a different spot from where his body was buried. His name was spelled wrong, and the year of his death was wrong. Even in death old Bill was making mischief. A new tombstone was placed in the correct place and corrections were made. The old one remained where it had been placed. Anyone familiar with old cemeteries wouldn’t be surprised.

One thing we do know about this mysterious, mild-mannered outlaw known as the “Gentleman Bandit.” He never killed anybody.

His principal biography is The Grey Fox: The True Story of Bill Miner, Last of the Old Time Bandits, by Mark Dugan and John Boessenecker (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992).

The popular 1982 film The Grey Fox, starring a popular, soft-spoken actor named Richard Farnsworth, who bore an uncanny resemblance to Miner. Farnsworth won a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actor and won Canada’s Genie Award for Best Foreign Actor. The movie also won Best Film.