It took John Joel Glanton a year to hit bottom.

The name John Joel Glanton probably doesn’t ring a bell. But in the 1840s into 1850, he made an impact that reached into two countries and affected Mexicans, Americans and Indians alike.

The South Carolina native was born in 1819; when he was old enough, he made his way west, to Arkansas and Louisiana and then Texas. Later legends said he was guilty of numerous violent acts, but there’s no evidence to back those claims. By 1847, he’d joined the Texas Mounted Volunteers as the Mexican-American War heated up. On November 24, Glanton was a member of a force that took on some 200 Mexican mounted lancers and drove them from the field. General Joseph Lane’s report commended several officers for their actions during the encounter; the only enlisted man who gained such recognition was Pvt. John Joel Glanton. He was a hero.

But that began to change in 1848. On November 15, Glanton ran into three disagreeable soldiers in San Antonio. All went for their guns; Glanton killed one and wounded the others. He acted in self-defense so a court acquitted him in the gunfight. But that effectively ended his military career. He and about a dozen men headed west to look for gold in California, but they ran out of supplies along the southern route and were stranded in Chihuahua.

In late 1849, Glanton and a few of his men found a new money-maker. Mexican authorities had put a bounty on the heads—well, literally, the scalps—of Apache Indians who had been conducting hit-and-run raids throughout Chihuahua. The Glanton group gladly joined in, obtaining an official contract from the Mexican government. But it was easier to turn in the black-haired scalps of Mexicans; it’s unclear just how many non-Apaches they killed and scalped. But when the governments on both sides of the Rio Grande sussed out the scheme, they branded Glanton and company as outlaws.

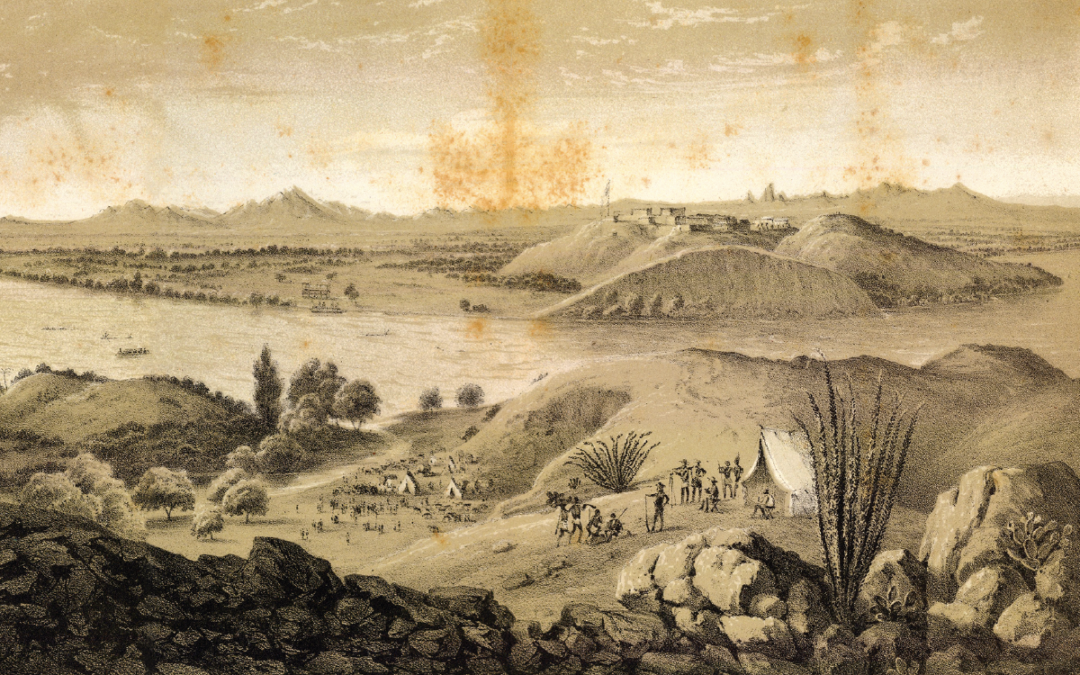

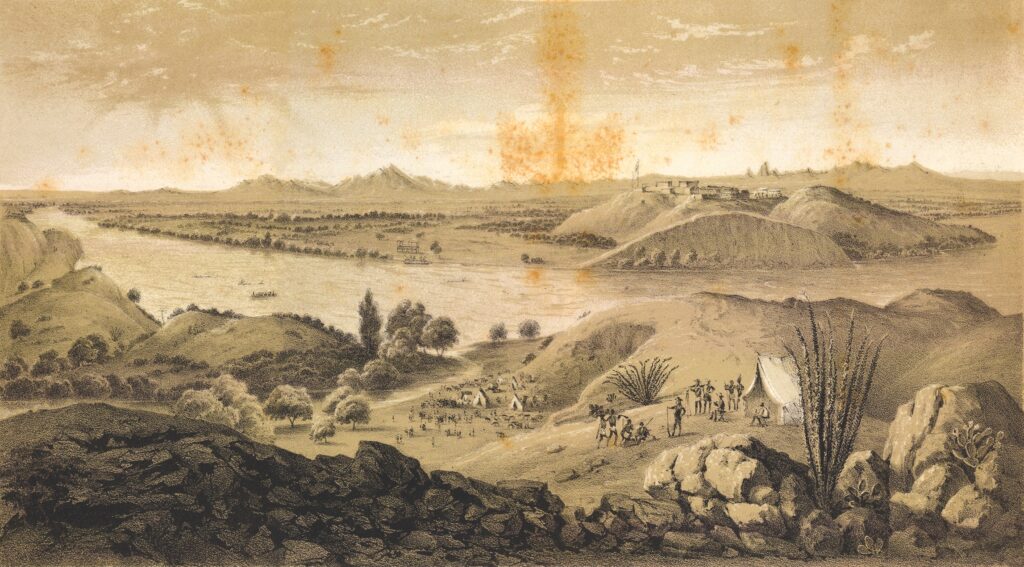

When that happened, the company started a ferry across the Colorado River in the State of Sonora, south of Arizona and California. Unfortunately, some Yuma Indians were already there and conducting their own business. The Glanton forces killed some, harassed others (including the chief) and took over. That was a mistake.

The normally peaceful Yuma people took up arms on April 23, 1850. Glanton and eight of his compatriots died in the encounter. Supposedly, his corpse was tied to that of a dead dog, taken back into U.S. and then set on fire. The Indians must have been pretty upset.

This sparked retaliation from American forces; the ensuing war went on—sporadically—for about three years before the Yuma soldiers surrendered.

Say this about John Joel Glanton: his activities had an international impact. And in the space of just over a year, he went from war hero to dead outlaw.