– Courtesy Lynda A. Sánchez Collection –

Caught between two worlds, Guadalupe Fimbres Muñoz had to make difficult choices for her future. She knew little of what was happening in the outside world when she was captured by Mexican rancheros in late 1914 or early 1915. A world war had begun, yet she had been at war since her birth as an Apache.

Captured

Apache Juan’s band was active during the last several months of 1914 or early months of 1915. One evening, after the Apaches had stolen 30 or more horses and cattle, and a large supply of corn, several angry Mexican ranchers formed a posse and went after the thieves.

The raw and rough country along the U.S.-Mexico border offered little-to-no law enforcement at that time, making ranchers on both sides of the border easy pickings. Some historians have attributed the survival of the Apache Kid and other renegades from the United States to this so-called rustling ring.

Near the top of Pico de la India, along the Sonora-Chihuahua boundary in Mexico, the ranchers located an abandoned encampment. From there, with the aid of field glasses, they spotted another that contained the missing livestock. They saw that the Apaches were breaking camp. The Mexicans split into three groups to intercept them.

Abraham Valencio was the first to enter the camp. He observed a young Apache on mule back, guarding the stolen herd. The youth, upon seeing Valencio, sounded an alarm, which sent his people into the underbrush. He stayed with the herd, trying to push the livestock off a nearby bluff to their death.

Lunging up the rugged canyon trail, straining under the whip of its desperate rider, the young Apache’s frightened mule snorted, fell back and then lunged again. The canyon was too steep, and the rider could no longer control the terrified animal, which bucked and balked with each lash of the whip.

Yells from below told the boy he was trapped. Mexicans were closing in on him. By the time the two other parties heard the shots and joined Valencio, the Apache youth was trying, in vain, to escape on foot.

The terror of this youth must have been great as he continued to run, descending down a cliff, jumping a steep arroyo and finally taking refuge in a small cave. With the prospect of death on the horizon, the Apache boy anxiously made a movement. One of the approaching Mexicans saw it and signaled the location to the vaqueros.

The Mexicans had no clue how many of the enemy waited. The men rushed the cave. The boy hissed and growled and fought, but eventually the vaqueros overwhelmed him.

The men were shocked to discover the boy was a girl, about 14 or 15. The cut girl was bleeding heavily. Indicating that this Apache was still a child, one man asked, “Has there not been enough violence?”

His sane voice in the heat of battle was a miracle. The men backed away from their original intent—death to the Apache.

The Mexicans treated her wounds. They then tied her onto a burro and took her to one of the Fimbres family ranches near Nácori Chico, Sonora, in Mexico, about 75 miles south of Douglas, Arizona.

Over the next several years, the girl who the family named Lupe attempted to adapt to a new culture, language and lifestyle. At first, she cried and would not eat. The Fimbres were so concerned about her wellbeing that they let her go twice, but twice she returned to their home, signaling that she was no longer a part of the Apache band. She had a difficult time learning Spanish, but soon became fluent, even though her intonation differed. She wove beautiful mats, hats and baskets, and learned how to sew.

Twelve years after her capture, Lupe’s life was jarred again. The 1927 kidnapping of three-year-old Gerardo Fimbres and the murder of his mother María by Apaches shocked the small mountain communities with their brutality.

The year 1932 was even more emotional for her: Mexican cowboy Aristeo García murdered an old woman said to be Lupe’s relative, either her mother or an aunt. Lupe found out about the killing from a child, perhaps four or five years old, Bui, who was captured during García’s attack on the Apache camp.

One of the owners of Rancho 31 (Los Laureles), where García worked as foreman, was Jack Rowe. Lupe had become friends with Jack’s wife, Margie. When Bui was brought to their ranch near Nácori Chico, Jack asked Lupe to come over and soothe the captured child. After hearing the devastating news from Bui, who became known as Carmela, Lupe abruptly departed Nácori Chico, never to return.

Carmela more easily adapted to life with her adopted family, another owner of

the ranch, Jack and Dixie Harris. Lupe had a harder time since she was much older, a teenager, when captivity changed her world.

Years later, Jack Rowe discovered that various academicians, including famed Mystery writer Earle Stanley Gardner, Grenville Goodwin, Dr. Helge Ingstad and Dr. Thomas Hinton, were all intrigued by the elusive Lupe and the lost Apaches.

Searching for Lupe

“They have absolutely no contact with any people outside themselves…. They are too wild, and it would be like trying to get in touch with a pack of wolves,” famed anthropologist Goodwin called the renegade Apaches, in 1934, in a letter he wrote to mentor Dr. Morris Opler.

Goodwin mentioned a girl in a Mexican village, Lupe, holding out hope that by talking to her, he could locate the remainder of the remnant Apaches, if in fact any still existed, and bring them back to the United States. He never located Lupe.

Four years later, the Ingstad Expedition of 1937-38 launched. Norwegian explorer Ingstad succeeded in interviewing Lupe. He met Lupe in Colonia Hernández, where she lived with her husband Perfecto Muñoz. She told Ingstad her story.

From birth, around 1900, until her capture in 1915, Lupe lived with a group of 12, mostly women, as well as a white man who had red hair (some historians have surmised he could be Charlie McComas, who, at age six, had been taken captive in 1883). The family moved around a lot, living in caves hidden in the cliffs along steep river valleys or in shelters of grass and saplings. They shod their horses and mules with hide to prevent anyone following them. Their weapons consisted of old rifles with poor ammunition, knives and bows and arrows. They ate mostly deer, mescal, the tops of onion shaped plants, honey, roots and berries. They made flour from acorns, mesquite beans and stolen corn. Cattle added variety to their diet. They made their clothes out of beautifully tanned cowhide or deerskin, and the women wore pants like the men. They lit small fires only during the daytime. They sometimes fashioned toys from twigs and dolls from cloth, horse hair and gamusa (buckskin).

Lupe spoke bitterly about the hated San Carlos Apache reservation in southeastern Arizona and how her people were forced to defend themselves against the Mexicans.

After her capture in 1915, she lived with several different Mexican families, including the Fimbres and Fuentes, on their ranches, until 1932.

Captive No More

In 1934, with the era of violence in the Sierra Madre coming to an end, Lupe married Don Perfecto Muñoz and lived with him at Colonia Hernández, near the Chihuahua/Sonora border in Mexico. Guillermo Soto of Casas Grandes provided one of the more vivid descriptions of Lupe. One year, when Soto was accompanying the jefe de armas (police chief) to Colonia Pacheco, he saw Lupe and her husband, Don Perfecto, ride in to visit with amigos. He said of her, “She rode like a man, and bareback. She leapt gracefully to and from her mount.”

Others also noted Lupe’s skills as a horsewoman and that she could ride con o sin montura (with or without a saddle).

– Courtesy Lynda A. Sánchez Collection –

Lupe “loved to dress up, fix her hair and to attend all the dances and really tirar chancla [kick up her heels]” remembered her daughter-in-law, Mercedez Muñoz. “She was a good dancer, too and was so nice everyone could not help but love her.”

Widowed in 1959, Lupe adapted by continuing her hard work and her devotion to family. Eventually, she left Colonia Hernández and moved to Colonia Juárez. In 1969, her great heart gave way to old age and exhaustion.

Lupe had helped raise Perfecto’s children and grandchildren, living the normal, everyday, hard existence of a resident in a mountain village. Yet she continued to avoid any contact with Federales or local military men, most likely haunted by memories when such authorities had hunted Apaches like animals. She also disappeared from time to time. Did she leave to meet survivors of her own Apache family? To reconnect to a world that has long since disappeared? To mourn the loss of her natural family?

No one will ever know.

The Apache Kid’s Daughter?

Few people, on either side of the U.S.-Mexico border, have been sympathetic to the Apache Kid’s history. He was a sadistic, violent outlaw—end of story. Then in 1995, Phyllis de la Garza’s The Apache Kid was published, which gave historians the opportunity to consider how a bright young man could have turned out, if he had been given a hand up instead of facing so many closed doors.

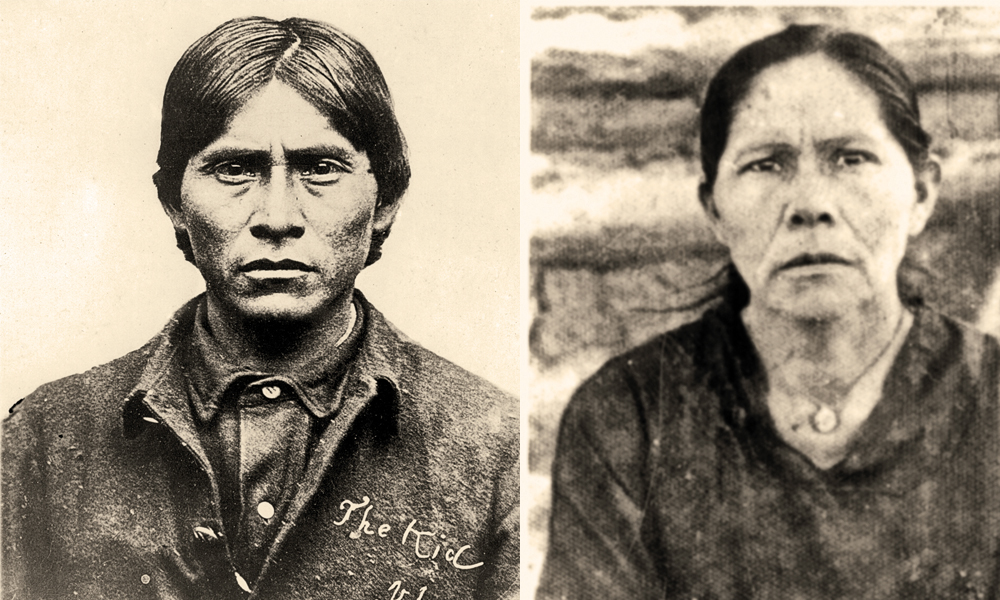

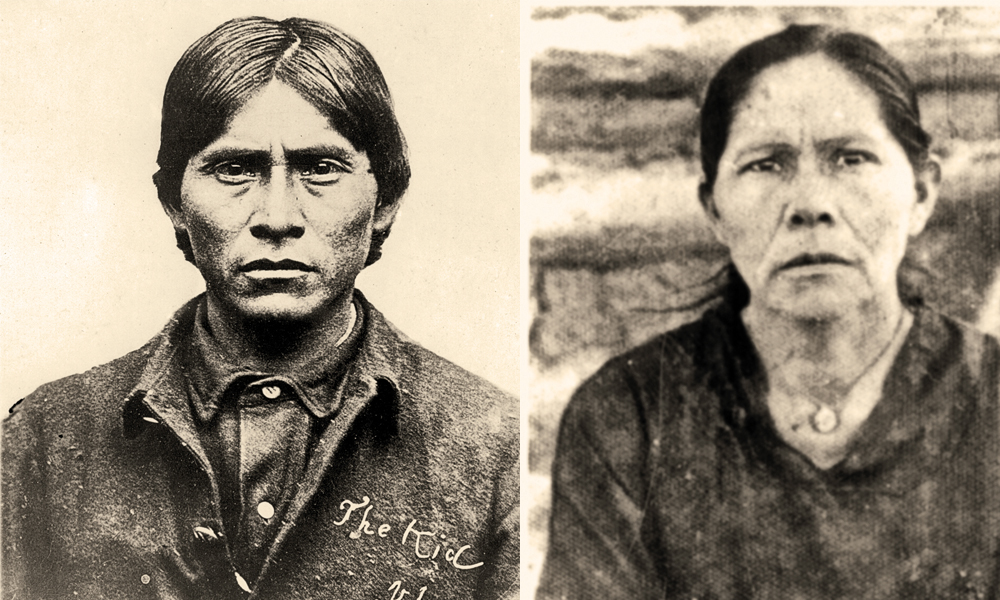

After reading de la Garza’s book, I have been haunted by the book’s cover photograph of the Apache Kid. By his eyes, his facial features, the set of his mouth. One afternoon, I casually laid the book on a table in my study, which had several photos of Lupe lying on it. I found the family resemblance between the two uncanny. But was I seeing one simply because I wanted to?

I called de la Garza and told her my thoughts on how Lupe being his daughter may not have been just another rumor among locals. I sent her a copy of my photos.

– Courtesy Fimbres Family, Lynda A. Sánchez Collection –

“I certainly agree that she looks just like Kid,” she responded. “Even her ears! Rather scary—the likeness is impossible to deny. The dates, time, place and circumstance ring true…. I don’t think we are imagining things here. The nose, the mouth, the chin, those ears, even the scowl. Also, bags under the eyes and the hair line. And, the fact she never bragged about being related to him, so she was not trying to gain some sort of notoriety, makes her revelation to Ingstad believable.”

Lupe had told Ingstad that her father was a great warrior, which he interpreted to mean her father was the Apache Kid.

Though historians will never know for certain, unless DNA analysis or some other modern forensic miracle can prove that relationship, I am among those who believe Lupe is not only Guadalupe Fimbres Muñoz, but also the daughter of the Apache Kid. Both of their lives were filled with violence and tragedy, yet each survived well into the 20th century, creating a niche for themselves as part of the fascinating Sierra Madre Apache saga. Lupe’s legacy is truly a greater piece of the “Lost Apaches” puzzle, that colorful and intriguing mosaic of history only now coming into its own.

Lynda A. Sánchez first visited Colonia Hernández in 1981 to interview the family of Guadalupe Fimbres Muñoz. Over several years of tracking the mysterious Apache woman some called the Apache Kid’s daughter, she interviewed members of the Fimbres/Fuentes, Muñoz and Whetten/Villa families. This article is one aspect of her research, which will be fully published in The Broken Loop: A History of the Lost Apaches.