It was a good day for Porter Rockwell. On April 15, 1847, the first Mormon wagon train under the leadership of Brigham Young was about to depart Winter Quarters, Iowa, on a westward journey to a promised land called Zion.

It was a good day for Porter Rockwell. On April 15, 1847, the first Mormon wagon train under the leadership of Brigham Young was about to depart Winter Quarters, Iowa, on a westward journey to a promised land called Zion.

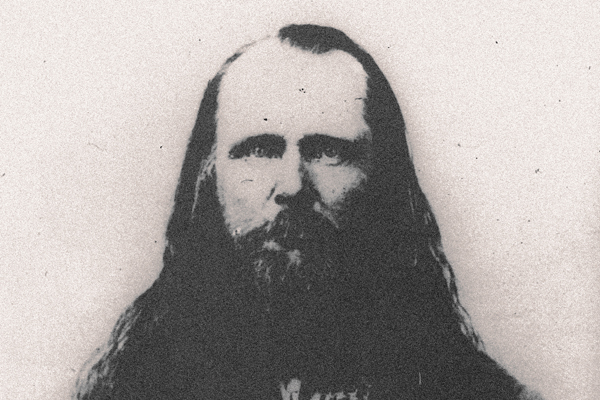

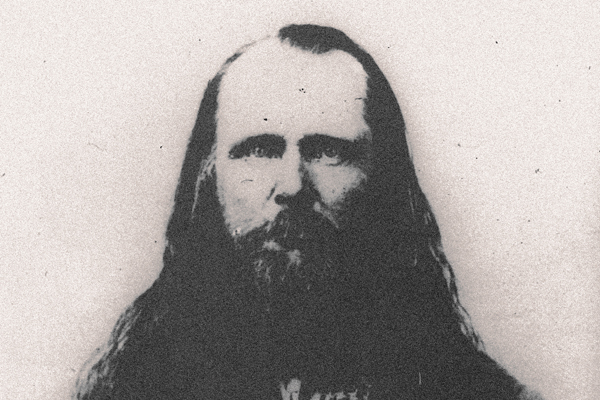

Rockwell was more than eager to assume his duties as head scout and hunter on the long trek west. The previous few years had been rough for the so-called “Mormon Assassin.” He was sought by Missouri lawmen for the attempted murder of Missouri’s former governor, Lilburn Boggs, whose expulsion orders had driven the Mormons out of the state in 1838. Rockwell had been on the lam, hiding out as far east as Philadelphia and the backwoods of New Jersey. Tired of life as a fugitive, Rockwell decided to take his chances with the law and head back to the Mormon haven on the Mississippi: Nauvoo, Illinois.

As he disembarked a paddle wheeler in St. Louis, Missouri, just two hours from safe harbor, he was recognized by two citizens who immediately stuck a gun in his face and placed him under arrest. After his nine-month stay in a dungeon-like cell in Independence, a grand jury found no evidence as to Rockwell’s guilt and he was set free. Now he was poised to embark on a new trail and a new life.

Standing tall among the rest

Rockwell’s first problem was which path to take west. The Mormon camp wanted to avoid the migration of Missourians and other gentile emigrants heading in the same direction. The decision was made to follow the north bank of the Platte River rather than use the more established Oregon Trail on the south side of the river. With miles of possible unfriendly Indians ahead plus the unknowns of crossing the Great Plains, there was good reason to avoid contact with people who had already made their feelings toward Mormons well known.

The trip was “uneventful,” for the most part. After being chased out of two states, shot at, spit on and generally despised by the populace of Missouri and Illinois, it was probably with a great deal of relief that the hearty group faced only hunger, thirst, hostile Indians, mountain fever, dust-choked trails and long weary days on foot. Just your average 1,000-mile journey.

Two weeks into the trip, the first buffalo chips were spotted. No buffalo, just chips. The pioneers quickly learned the use of the bovine by-product, and groups of children formed to collect the new fire source. When the first buffalo herd was finally spotted, every able-bodied man with a horse and weapon gave chase. One man stood tall among the rest. The long haired, black-eyed Rockwell maneuvered his horse into the large herd and started dropping buffalo like ducks in a shooting gallery. As the dust and blackpowder smoke cleared, people watching the action from the wagons and other hunters applauded Rockwell’s performance. A fine buffalo barbecue took place that evening.

Avoid Salt Lake Valley

Late June found the group in present-day Wyoming. Close to the Little Sandy River, they met up with three trappers, one of whom just happened to be Jim Bridger. Brigham Young talked Bridger into staying the night and picked his brain on the land in the Great Basin. Bridger told the entranced travelers that the Salt Lake Valley was the last place they would want to settle. Conditions for farming in the valley were so unsatisfactory, he supposedly offered a thousand dollars for the first bushel of corn grown there.

No matter. Young had made up his mind. “It is the Lord’s choosing, not Brigham Young’s,” he said. The weary band entered the Great Salt Lake Valley around July 24. Young, who was delirious with fever, rose from his sickbed to declare, “This is the place.”

The years 1847-49 saw Salt Lake City begin to prosper. It became a major stopping/shopping point for emigrants traveling west to California. Rockwell spent his time confabulatin’ with the local Indian tribes and scouting for water sources, timber and game. Most important, he was a regular link with the thousands of Mormon emigrants traveling west. With Rockwell riding between Nebraska and the Utah Territory, keeping each company apprised of one another, delivering mail and directing group leaders to prime campsites and hunting locations, he kept the mass exodus moving smoothly.

Rockwell is sent to collect

During this time, Samuel Brannan was the leader of a small band of Mormons that settled in Yerba Buena, California, later to become San Francisco. They had sailed from New York, around Cape Horn, with a rest stop in Hawaii. After six months at sea, the group had landed in Yerba Buena in late July 1846. Being the spiritual as well as temporal leader of the group, Brannan was in charge of collecting the 10 percent tithes the Latter Day Saints freely gave to build up the kingdom of the Lord. Brannan, however, seemed to be using the funds to build up his own kingdom. By spring 1849, none of his collections had made it to Salt Lake City.

Brigham Young was tired of waiting for Brannan to pony up all the tithing money he had raised since arriving in California. It was time to collect. Young chose a trusted apostle, Amasa Lyman, to deliver the written request asking Brannan for $10,000 owed the church. He also picked Rockwell to act as “the negotiator.”

Rockwell and Lyman rode into Sutter’s Fort a month after leaving Salt Lake City. Rockwell headed straight for the goldfields, while Lyman started to proselytize and collect tithes from the brethren that were left in the immediate area.

Flight to the Zion Curtain

Rockwell had some luck with the pan and the pick, and before long he had opened three business establishments around the American River: Round Tent Saloon at Murderer’s Bar, an inn at Buckeye Flat and a halfway house by Mormon Island. A man can only cross the prairie and get shot at by Indians and bodyguard prophets so many times before he needs a little R and R; however, with lots of Missourians also looking for gold in the area, Rockwell began using an assumed name: John B. Brown.

In January 1850, seven months after the duo had arrived in California, Lyman found Rockwell and convinced him they had better finish their business with Brannan before they both incurred Young’s wrath. They met with Brannan in his spacious San Francisco home. By this time, Brannan had become a leading citizen of San Francisco. “We’ve come for the Lord’s money,” Lyman told Brannan. “Give me a receipt from the Lord … and you can have his money,” Brannan replied. Brannan’s refusal got him expelled from the Mormon church.

Rockwell didn’t put the muscle on Brannan for a number of possible reasons. Former Missouri Gov. Boggs, who had put a hit out on Rockwell after his assassination attempt on the governor, was now the mayor of Sonoma, which was right down the road from Rockwell’s properties. Plenty of Missourians in the region would have liked to see the “assassin” swinging by the neck. Also, Brannan was now a well-respected and influential businessman in San Francisco. (In 1851, he would head San Francisco’s vigilance committee, whose first act of vigilance was to publicly hang a local thief.) Rockwell’s use of an assumed name leads one to believe he must have been looking over his shoulder.

An incident at Rockwell’s halfway house prompted his move back to the safety of the Zion Curtain. Rockwell was challenged to a shooting match by a fellow store owner for a prize of $1,000. A large crowd of miners quickly gathered. The money and whiskey flowed as the two marksmen dueled.

When Rockwell was declared the winner, the party got wilder. The man who had lost the match knew Rockwell’s real identity and proceeded to shout it out at the now completely drunken mob. A sober Rockwell managed to escape by the skin of his teeth. After 19 months in California, Rockwell headed home.

End of the track

After Rockwell’s return to Utah, his reputation grew to legendary proportions. Stories of heinous murders of gentiles traveling west, killed either for booty or just for Danite revenge, were talked about in whispers. Rumors also spread that any apostate Mormon who spoke out against the church in public or private might meet his maker at the hands of the territory’s most famous hit man. For the children of Utah, Rockwell became their official boogey man.

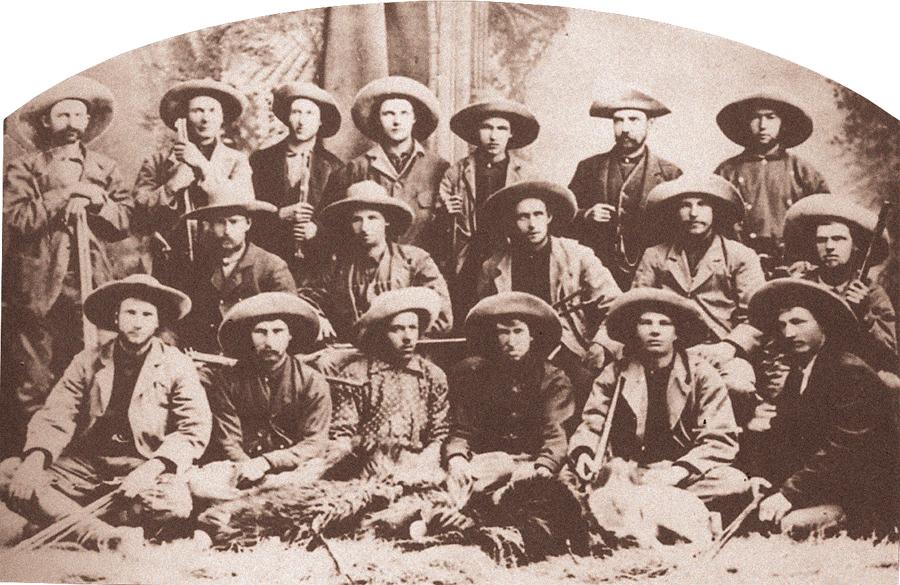

When Col. Albert Sidney Johnson’s army marched toward Utah in 1857 for the so-called Mormon War, Rockwell was named captain of a 100-man ranger company to lead guerrilla raids against the insurgent army to “disrupt supply trains and harass military columns.”

Rockwell was never brought to trial for any of his alleged crimes. After the death of Brigham Young in 1877, the judiciary non-Mormon powers proceeded to indict suspected felons with no thought to passage of time or lack of credible witnesses. Rockwell was indicted for the murder of two California men some 20 years prior. While free on bail, he died of a heart attack just hours after he and his daughter had attended a play at a Salt Lake theatre.

The 65-year-old Mormon Assassin died in bed with his boots off.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –