“As far as I could see, covered wagons stood one beyond another in a long, long line. Behind them and over them, high over half the sky, a yellow wave of dust was curling and coming. My mother said to me, ‘That’s your last sight of Dakota.’”

“As far as I could see, covered wagons stood one beyond another in a long, long line. Behind them and over them, high over half the sky, a yellow wave of dust was curling and coming. My mother said to me, ‘That’s your last sight of Dakota.’”

Rose Wilder Lane recorded her memory in On the Way Home, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s diary of the family’s trip in 1894 from South Dakota to Mansfield, Missouri.

Tucked inside Laura’s writing desk was a $100 bill that she had earned working as a seamstress in De Smet, South Dakota. The money was to buy land in Missouri, allowing the Wilders to make a fresh start.

Laura, who later became famous for her Little House books, had moved to De Smet in 1879 with her family. Six of her books depicting pioneer life are set in the town, but Laura’s first publication, in the De Smet News and Leader, resulted from her 650-mile journey to Missouri with her husband Almanzo and their daughter Rose.

The Wilders were married in De Smet in 1885, and Rose was born the next year. Beset by years of drought and failed crops, a bout with diphtheria that sickened both Laura and Almanzo and left him crippled, the death of an infant son and a fire that destroyed their home, they decided to begin a new life elsewhere. They tried Minnesota and Florida before settling on Missouri.

The move meant leaving behind Pa and Ma Ingalls and Laura’s sisters, Mary, Carrie and Grace. The close-knit family lived in the railroad surveyor’s house, a “two-story mansion,” as Laura called it, when Pa worked for the railroad.

Today, in De Smet, you’ll still see covered wagons and you can ride in one when you visit the Ingalls homestead, a mile southeast of town. Five cottonwoods stand on the one-acre claim now, part of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Memorial Society’s properties. The prairie has been left as it was when Laura and the Ingalls family lived here.

In town, guides dressed in calico and sunbonnets lead you through the surveyor’s house where the Ingalls stayed during their first winter in Dakota. You’ll also want to visit the two-story wood frame home that Charles Ingalls built in 1887. It’s filled with various items of the Ingallses and stories about each family member. The family cemetery rests on a nearby hill and contains the graves of Charles, Caroline, Mary, Grace and Grace’s husband, as well as Laura and Almanzo’s infant son.

A “Discover Laura” center is open through the summer, offering youngsters the opportunity to wear period clothes, sew with a treadle sewing machine, learn to write their name in Braille as Mary Ingalls did and decide how to pack a covered wagon for a lengthy journey.

Heading to Missouri

The Wilders started for Missouri on July 17, 1894, in scorching heat and reached Yankton, South Dakota, six days later. Yankton was not as large as De Smet at that time, but today it has grown into a thriving city. The riverboat town was a stop on the Lewis and Clark expedition, and present-day tourists and locals enjoy recreational activities at Lewis and Clark Lake, as well as an annual August festival honoring the explorers at Gavins Point Dam. You can approximate the Wilders’ route by traveling south from De Smet on Highway 25 to Canova, turning east and taking Highway 81 south to Yankton.

Crossing into Nebraska, the Wilders passed through Hartington, Coleridge, Stanton and Schuyler, with Laura remarking in her diary about the “sleek cattle,” cornfields “3 miles long” and the many German settlers they saw in the region.

On August 3, they reached Lincoln, the capital of Nebraska. Laura deemed it “a beautiful large city,” and it still is. Today’s visitors enjoy seeing the elegant, taper-like column of the State Capitol miles before reaching the city. The Museum of Nebraska History, containing a wealth of material on the American Indian and other Plains information and artifacts, and the Great Plains Art Collection, including Frederic Remington and Charlie Russell sculptures, delights history buffs and others interested in the past.

The Wilders followed the telegraph poles to Beatrice, but today’s travelers take Highway 77 south. The courthouse Laura described as “handsome” is still a must-see, and a short drive west from town on Highway 4 brings you to Homestead National Monument, the site of Union soldier Daniel Freeman’s homestead claim, the first in the nation. Freeman signed up for his land shortly after midnight on January 1, 1863, the day the Homestead Act took effect, allowing citizens and those who planned to become citizens to claim 160 acres of surveyed government land. The settlers had to remain on the land for five years to obtain title to the property. An 1867 cabin stands in the park today, with a restored tallgrass prairie nearby.

Marysville, Kansas, was the next stop for the Wilders, and today a historic Pony Express station is available for touring. When the Wilders headed southeast to Topeka, Laura remarked on the Kansas capital’s electric street cars and the prevalence of dust in the region. Their route took them farther south to Ottawa and Fort Scott, a town filled with emigrants. Fort Scott was a bustling rail center in the 1890s, with seven lines passing through town. Laura described it as “a bower of trees,” still an apt portrayal.

Today’s visitors can climb aboard a bright green trolley and tour the city, enjoying the architectural charm of the numerous Victorian mansions still in use, many of which retain original carriage steps and hitching posts. The tour also takes you past National Cemetery Number One. The fort, named for Gen. Winfield Scott, was established in 1842, with the First Regiment of U.S. Dragoons in charge of protecting the frontier. The fort’s buildings have been restored, and authentic touches, like playing reveille, delight visitors as they stroll the grounds.

Laura’s new home

Highway 54 east takes you across the border into Missouri, where you’ll follow Highway 71 south and then Highway 160 east at Lamar to pass through the towns of Golden City and Greenfield as the Wilders did. This rollercoaster road with many winding turns and hills also passes through Ash Grove, another Wilder stop, and brings you to Springfield.

Laura deemed it “simply grand,” and that rings true today, especially with the city’s rich Civil War history. She had purchased a revolver before she and Manly, as Laura called her husband, began their travels. No doubt she felt safer with that weapon during her time in Missouri, the third most fought over state during the Civil War.

While Springfield is best known as the site of the 1865 town square shoot-out between Wild Bill Hickok and the unfortunate Dave Tutt, and for its prominent location on the famous Route 66, Wilson’s Creek Battlefield, now a national park, is located about 10 miles from the city and is a must-see for anyone interested in the nation’s history. The Battle of Wilson’s Creek, fought on August 10, 1861, was a fierce and bloody struggle for Missouri. Union forces fell (but regained control in 1862); their commander, Nathaniel Lyon, was killed during the conflict, becoming the first Union general to die in battle during the war. He was taken to the Ray house, which served as the Confederate hospital before and after the battle. The structure and its springhouse are the only surviving war buildings in the park. Springfield is also the site of a national cemetery, containing the graves of Union and Confederate soldiers and a Revolutionary War soldier. The History Museum located in City Hall is also a worthy stop, with its impressive display of artifacts.

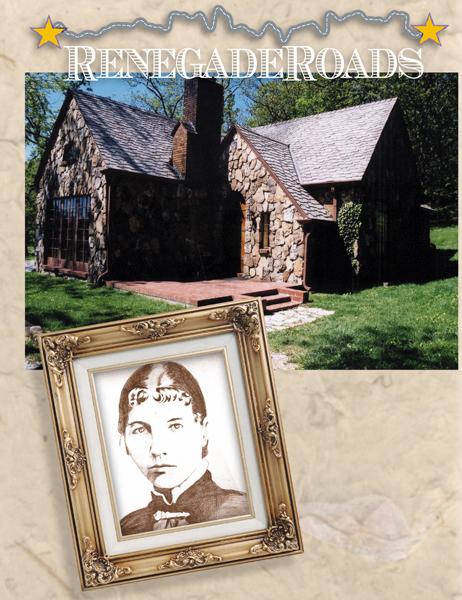

Driving east on Highway 60 for about an hour brings you to Mansfield, the small town where the Wilders made their home, now site of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Home and Museum. Keep keen eyes on the road for the Amish buggies traveling the highway near Seymour. Just one mile east of Mansfield stands the charming two-story wood frame home Almanzo built for his wife. Kitchen counters were made to suit Laura’s diminutive size, and numerous items they cherished, like her favorite rocker and pump organ, are still on display here, where Laura wrote many of her Little House books. Pa Ingalls’ fiddle is housed in the museum, as is Laura’s revolver, along with other memorabilia, such as Rose’s desks and souvenirs from her world travels as a noted author.

The $100 that led the Wilders to their dream of a better life proved a wise investment, and a generous one, for Laura continues to share it by teaching us of pioneer life in her books.

Photo Gallery

(Left) Laura Ingalls Wilder at age 17. The next year, she married Almanzo Wilder, who she met while earning her teaching certificate in De Smet, South Dakota.

– Wilder Rock House by Lori Van Pelt; Laura Ingalls Wilder Portrait courtesy Laura Ingalls Wilder Memorial Society in De Smet, South Dakota –

– Harper Trophy series illustrated by Garth Williams –