.jpg) One hundred years ago, Willie Nickell, the 14-year-old son of a contentious homesteader who had brought sheep into cattle country, was murdered on July 18 near the family homestead in the Iron Mountain region northwest of Cheyenne.

One hundred years ago, Willie Nickell, the 14-year-old son of a contentious homesteader who had brought sheep into cattle country, was murdered on July 18 near the family homestead in the Iron Mountain region northwest of Cheyenne.

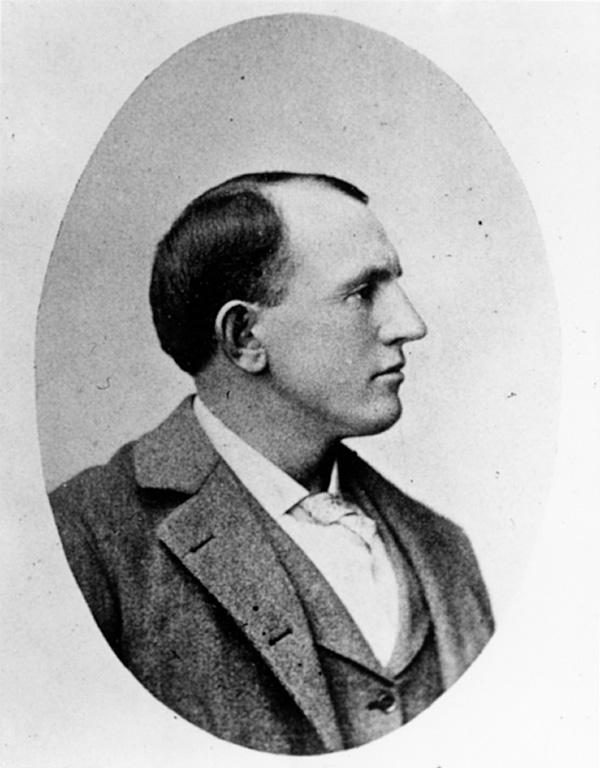

After a six-month investigation, Deputy U.S. Marshal Joe LeFors tricked cattle detective Tom Horn, a feared agent of the cattle barons, into making a series of drunken remarks that were used as his confession to the crime. He was convicted and hanged in Cheyenne on November 20, 1903.

Cattle detectives, or “stock detectives” as they were often termed, were employed in Wyoming from 1873 into the twentieth century to patrol vast grazing ranges. While the range business was at first enormously profitable, it soon suffered from absentee ownership, mismanagement, devastating winters, incursions by homesteading settlers and rustling. The barons, however, attributed their problems to the rustlers.

A series of events took place that reflected their attempts to maintain the status quo, drive out newcomers and effectively turn the clock back. Cattle detectives were often the barons’ instruments.

The most infamous of the cattle tycoons’ acts was the Johnson County Invasion in April 1892. The Invasion, or Johnson County War as it is also known, was an armed incursion into central Wyoming in April 1892 organized by some of the new state’s largest cattlemen. Its purpose was to drive out or kill dozens of parties who were believed to be rustlers or their sympathizers, and allow the cattlemen to install their own puppets.

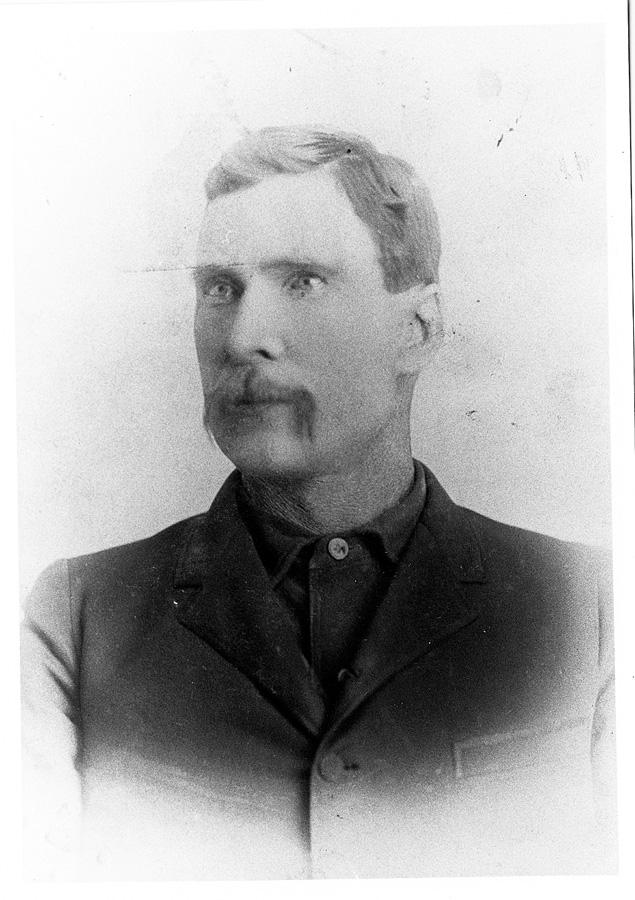

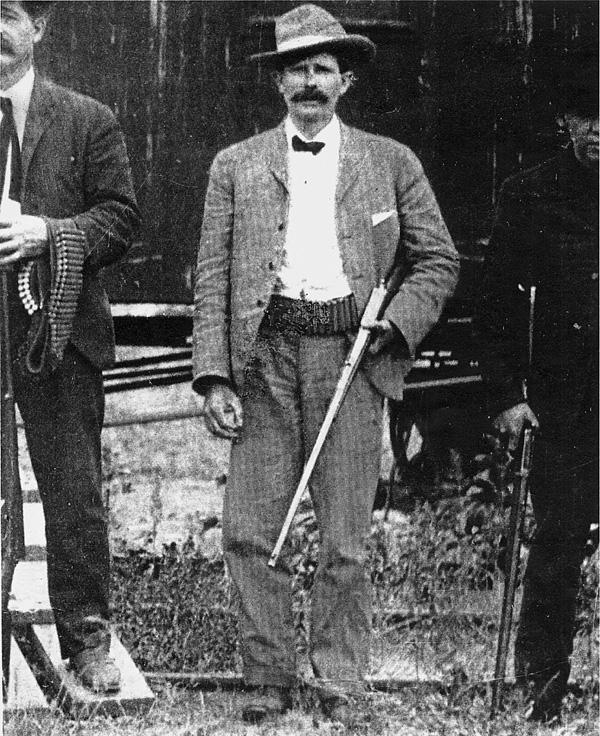

Tom Horn, who arrived at the time of the Invasion, was the most infamous of the range detectives. The incursion failed, and after, Horn became a deputy U.S. marshal in Johnson County (under an alias he had previously used when a Pinkerton’s agent). Working as a detective for the Swan Land and Cattle Company, he arrested a gang of rustlers in the Sybille country in 1893, only to see all but one released by the court. At that point, he began building his notoriety for taking the law into his own hands.

He was linked to the assassinations of two settlers, William Lewis and Fred Powell, in 1895. Although he was exonerated, being connected to the killings helped build his reputation. At one point, he told Wyoming’s Governor W.A. Richards that when all else failed, “I have a system that never does.” To the homesteaders, Tom Horn became the devil incarnate.

The following article covers the events that led to the Willie Nickell murder. It was Tom Horn’s presence near the site of the assassination that first connected him to the crime, but a closer examination of the circumstances leads to a conclusion that someone else murdered the teen.

It was only a wire gate northwest of Cheyenne where it happened. It was known only to a handful of local homesteaders and ranchers in the area at the turn of the century. On July 18, 1901, after the blood of a 14-year-old boy sprayed over it when he was struck by two .30-caliber bullets, and after he stumbled 65 feet toward home a mile away falling face down, it became something much greater. It became the site of the most famous murder in Wyoming history. It became the scene bragged about by the most famous, or infamous, cattle detective in the West. And when a drunken Tom Horn bragged about the killing, the boast led to his hanging two years later.

The tragedy was the second involving a teen in less than a year in the remote Iron Mountain country. As with most teen deaths, it was needless. The boy, and another 14-year-old killed in August the previous year, died. And, it seemed then and now, that one of the fathers was to blame.

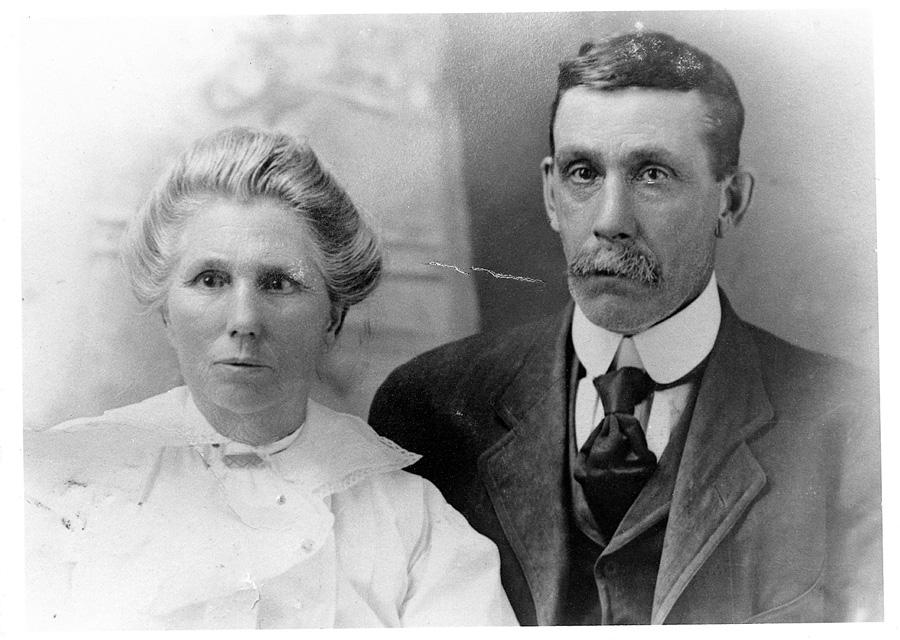

Willie Nickell’s father, Kels P. Nickell, had moved into the Iron Mountain area in 1885, where he established a homestead on North Chugwater Creek. A Kentuckian, he married Mary Mahoney, a sixteen-year-old Irish immigrant at Camp Carlin, west of Cheyenne. Two children, Julia and Kels, junior, were born there. Willie was born in 1887 at Iron Mountain. Six more children followed before the turn of the century.

Jim and Dora Miller had settled at Iron Mountain two years earlier, after moving from Greeley in a covered wagon with their first child, Gus, who was born in 1882. Victor was born at Iron Mountain in 1883, followed by Eva in 1885, and Frank in 1887. Seven more children were born to the couple. The Miller place was on a tiny stream, Sawmill Creek, where it feeds into Spring Creek. It was a mile south of the Nickell homestead.

Feuds soon broke out between the two fathers, for reasons that are still unknown today. The two older Miller boys also became embroiled, as did Willie Nickell, in the feuds between the men.

What is known is that Kels Nickell, a hothead, was paranoid. Over time, he warred with all his neighbors. On July 23, 1890, he knifed John Coble near Nickell’s property line to the west. Coble ended up in the hospital, but recovered after a few days. This event may have been the first blood that was shed in Nickell’s quarrels. It was, perhaps, an omen of fatal events to come, for Coble was to become one of Tom Horn’s chief employers and best friend.

Another of Nickell’s early disputes reflecting indifference or scorn for his neighbors was an incident in June 1891. Nickell built small dams along the North Chug, as it was known, thereby diverting the stream and depriving property owners downstream from having use of the water. Herbert Woodyer sued him for $500 for the illegal act. It is not known if a judgment was entered, but an injunction signed by Judge Richard H. Scott resulted in a restraining order being served onNickell by Sheriff A.D. Kelly on June 24.

The strife between Nickell and Jim Miller, however, was the most virulent. At one point, a knife fight broke out between the two on the train between Cheyenne and the Iron Mountain depot. Over the years, there were petitions to the court by each to have the other placed under a peace bond. At a neighborhood meeting held at the home of A.F. Whitman, tempers flared to the point that one rancher proposed lynching Nickell for stealing cattle. Nothing came of the proposal, but only because Whitman himself told the group that no one was going to be lynched on the basis of hearsay.

Tom Horn knew of the past doings of both Nickell and Miller, and referred to both men with disdain:

“They are a class of people I have no regard for. They are isolated; they don’t come in contact with any people I represent.

“At the same time, there was a time when they were pretty pronounced thieves. All the cattle they have, they started from Two Bar [a Swan Land and Cattle Company ranch] and Coble cattle. They have been honest within the last five or six years, but formerly they were not considered anything but rustlers, that is, by the larger stockmen. I know that each of them acquired his herd with nothing but a rope.”

By 1900 the passions flared to the point that Nickell and Miller each began carrying guns. Miller remarked that he never even went to the privy without his six-shooter. Julia Nickell stated that she knew that Miller had bought a gun for one reason, saying, “He has been making threats around the country. I heard Will McDonald tell Papa that once. Mrs. McDonald told me that he had laid out in the pasture to kill Papa time and again. The last time we come to town I understood he bought a new gun for the purpose of killing Papa, that he was not going to give him any chance.”

Matters grew worse in the spring of 1900. Nickell began making threats to bring sheep into the country. That in itself was bad enough, for his ranch lay well north of a border beyond which no sheep were to range. But Nickell then threw more fuel onto the fire by bragging that he was going to push the sheep onto all the neighbors’ ranches. He had one purpose in mind, he said—to do them in.

He promised that when he got finished with John Jordan’s ranch, there would not be “enough grass left to feed a goose.” Jordan was one of the largest ranchers at Iron Mountain, and one of Tom Horn’s employers.

By the time Nickell was ready to bring in the sheep, Tom Horn knew all about his intentions. When queried about the neighborhood, and particularly the cattlemen’s reaction to Nickell’s plans and reputation, Horn replied, “Their sentiment is that a man that would do as Nickell has, could only do so, being the kind of man Nickell is, troublesome and quarrelsome, a turbulent man without character or principle.”

In August 1900, a tragedy less well known occurred when Jim Miller’s 14-year-old son, Frank, was killed when a shotgun accidentally discharged. Frank and a younger sister, Maude, were playing in a spring wagon when the gun, left there by their father, fired. A load of buckshot hit Frank in the head, killing him instantly. Maude carried pockmark scars from the accident for the rest of her life.

Miller’s resentment over this incident grew, but characteristically he did not act at once. He did, however, speak his mind. Lillie Graham was visiting her mother and stepfather at Iron Mountain when Jim Miller stopped by. Graham said:

“I was visiting my mother and stepfather there just after Franklin Miller was accidentally shot when his father, Jim Miller, came to the Edwards home on his way to Cheyenne. He stated the object of his going to Cheyenne was to have Kels Nickell prosecuted or bound over to keep the peace. He said, ‘I will never rest until that boy’s death is avenged and if the law does not do it, I will.’”

By the next spring Nickell had sold his cattle. In May 1901, he acquired 3,000 sheep near Loveland, Colorado, and arranged for a herder, John Scroder, to drive them north to Iron Mountain. West of Cheyenne, with Nickell accompanying him, Scroder heard one passerby who remarked, “Nickell, you won’t live to see the year 1902 if them sheep goes in there,” foretelling the violence to come.

Tom Horn knew what the reaction would be to the arrival of the sheep. “Every cattleman I have heard talk, and I have heard a great many, say it was not right, and say so in very strong terms. I know the sentiment and feeling of cattlemen. They say if he had started in the sheep business it would be different. Being in the cattle business and deliberately selling his cattle and putting sheep in, for no other reason than to spite the neighbors, and to do them dirt and damage and ruin them if he could, and boast of it, then he would tell these people how he was going to do them up.”

And Tom Horn was already aware of the explosive situation brewing between Nickell and Miller.

Such were the conditions in 1901 as spring became summer in the Iron Mountain country.

On a patrol to check his employers’ pastures, Tom Horn arrived at Billy Clay’s ranch on Sunday, July 14. He worked the pastures, had his noon dinner at Clay’s, and continued inspecting the range. He returned in the evening, spent the night at Clay’s, and left Monday morning. Around 10:00 in the evening he arrived at Miller’s ranch, after the family had retired. Reaching the home, he called out. Miller climbed out of bed. On the way to the window he pulled on his pants, reached for a six-shooter, and called, “Who is it?”

“Horn,” the detective replied.

“Turn out your horse, come in and have something to eat,” said Miller.

Horn slept that night in a tent with the Miller boys, Gus and Victor. The next morning he spoke with a schoolteacher, Glendolene M. Kimmell, who was boarding at Miller’s while she taught at the school where the Millers and Nickells attended.

After she left for work, he saddled and mounted his horse and rode west. It was then that he first observed Nickell’s sheep on Miller’s land. He reported their presence to Miller. Later in the day, he fished and practiced target shooting with Miller. When the schoolteacher returned, he spent much of the afternoon visiting with her. One of the Miller boys said he made a “very good impression” on her, and that she seemed “stuck on him.”

In the early evening, Horn made another patrol and again reported that Nickell’s sheep were trespassing.

Events began to accelerate leading to Horn’s departure and Willie Nickell’s murder.

Tom Horn described what happened before he left, in a letter he penned to John Coble only minutes before his hanging. It seems that he had something he wanted to get off his chest. The letter may very well tell what really happened just before Willie Nickell died.

He wrote that Billy McDonald stopped by Tuesday evening, and they met with Miller. “Billy opened the conversation by saying that he and Miller were going to kill off the Nickell outfit, and wanted me to go in on it.”

John Jordan and John Underwood (another major cattleman in the region) would pay him, McDonald said. Horn refused to have anything to do with them but agreed, at Miller’s urging, to stay another evening because McDonald would come by the next day.

The next morning, Wednesday, Horn again visited with Miss Kimmell until she left for school.

He continued in his letter to Coble that McDonald arrived and asked him if he “still felt the same way.” Horn said he did. At that, McDonald told him that he and Miller had decided to “wipe up the whole Nickell outfit.”

Horn left mid-morning, and was not seen again until John Braae observed him on a ridge well to the north of Billy Clay’s near sunset.

At 7:00 a.m. the next day, Willie Nickell was gunned down three-quarters of a mile west of the family home. The killing occurred at what would become the most famous gate in Wyoming history.

Ninety years later, a descendent of Jim Miller commented, “Someone knew Willie would be there that morning.” The remark leads to the question, who was that “someone,” and how did that “someone” know?

Descendants of Miller-Nickell neighbors continue to speculate, offering no solid conclusions. One hundred years after, all we know for certain is that innocent blood spilled for no good reason, the wrong man may have swung from a rope, and whoever the killer was may have lived.

The lingering dispute—over who actually murdered the boy, coupled with the controversial trial of a hated agent of the barons—has made the event one of the most famous in the annals of the West.

Chip Carlson has written for True West, authored numerous historical articles and two books on the Horn episode, Tom Horn: Killing Is My Specialty, and Joe Lefores: I Slickered Tom Horn. His third book, Tom Horn: Blood On The Moon, will be released by High Plains Press in mid-2001. Carlson is a long-time resident of Cheyenne, Wyoming.

You can reach Carlson at: chipcarlson@hotmail.com

High Plains Press can be reached at P O Box 123, Glendo WY 82212 or at (800) 552-7819 and editor@highplainspress.com.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy of the Wyoming Division of Cultural Resources –

– Author’s Collection –

– Courtesy of the Wyoming Division of Cultural Resources –

– Author’s Collection –

– Author’s Collection –

– Wyoming State Archives, Museums and Historical Department –

– American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming –

.jpg)