“Our Land Marks Gone,”. . . the headline blared in the Globe Live Stock Journal on Tuesday, December 1, 1885. “THE FIRE FIEND WIPES OUT THE BUSINESS HEART OF OUR TOWN.”

“Our Land Marks Gone,”. . . the headline blared in the Globe Live Stock Journal on Tuesday, December 1, 1885. “THE FIRE FIEND WIPES OUT THE BUSINESS HEART OF OUR TOWN.”

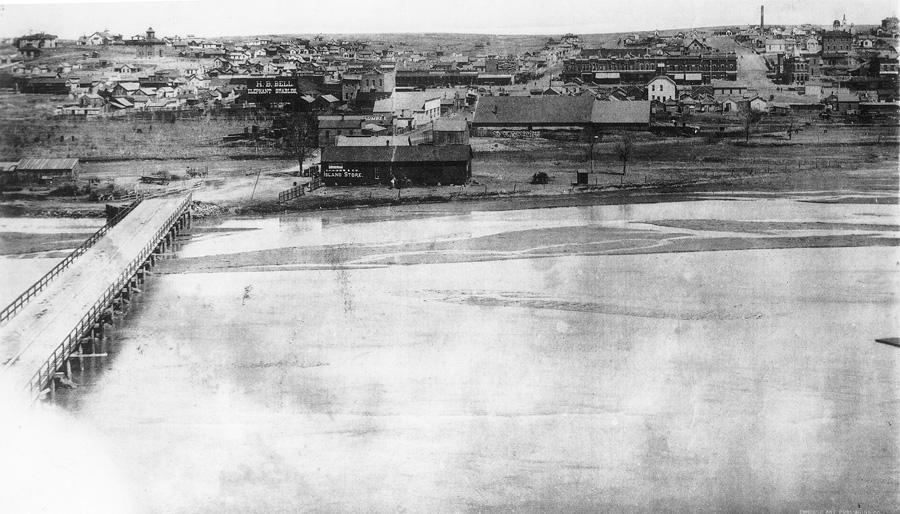

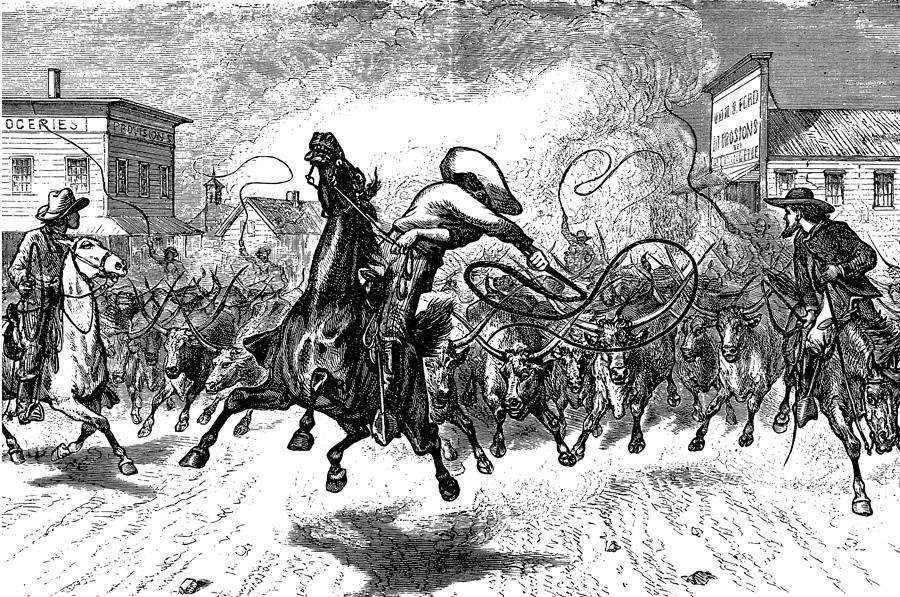

For residents of Dodge City, Kansas, the news seemed all too familiar. The conflagration of November 27 was the second major fire to strike the business district in the Queen of Cowtowns (the first in January), and there was more smoke on the horizon. Less than a week after the Journal’s coverage of the second fire, the “fiend” would struck again.

Like many Western frontier towns, most of them tinderboxes by today’s standards, Dodge City had witnessed its share of fires, common in rows of frame buildings. But early outbreaks had been put out quickly by volunteers, and until 1885, Dodge City had not witnessed any fires that had cost insurance companies. That changed on January 18—ironically, the day after the Kansas Cowboy commented on the lack of damaging fires in the city. The subsequent fires of November 27 and December 7, as well as two smaller fires in 1886, would result in few injuries—and apparently no deaths—but would literally change the face of the town’s business district.

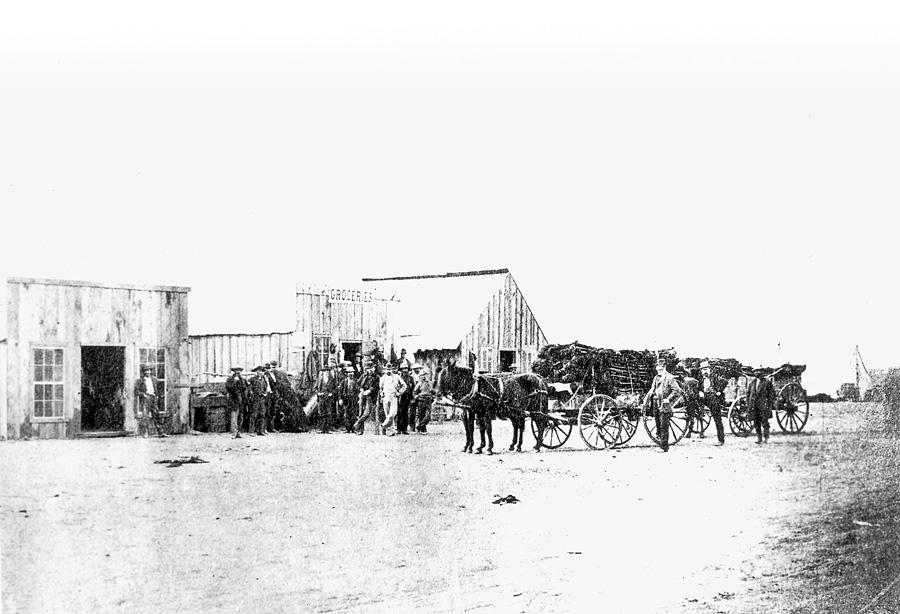

On the afternoon of Sunday, January 18, 1885, a fire broke out in the cellar of Perry Wilden’s grocery store on Front Street between Second and Third Avenues. Flames shot from the windows, and before long, the Union restaurant, next door to Wilden’s on the west side, ignited. The Kansas Cowboy said that the restaurant “ended in smoke at the drop of the hat.” Editors of the Cowboy might have regretted the fire report printed the day before. The newspaper, located on the second floor of a building two doors west of Wilden’s, lost a power press and “a large portion” of type.

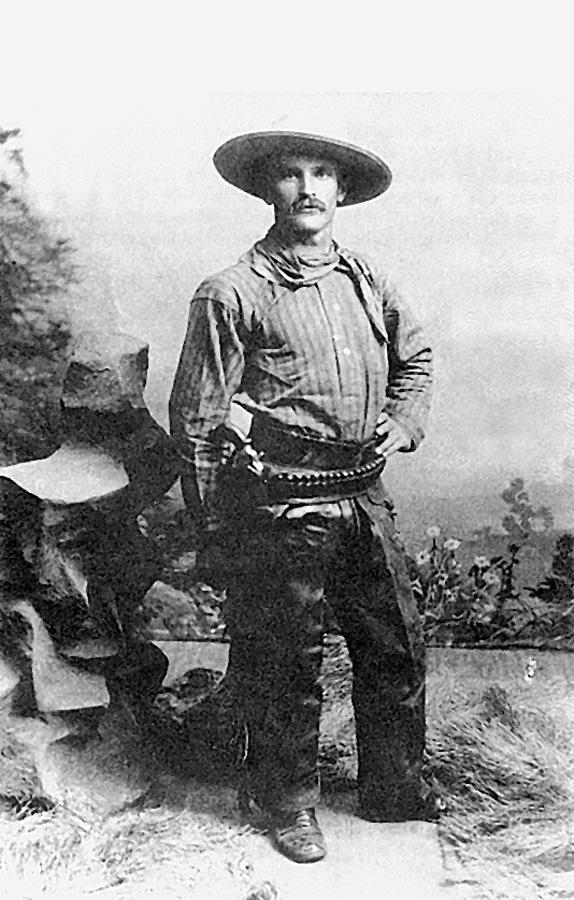

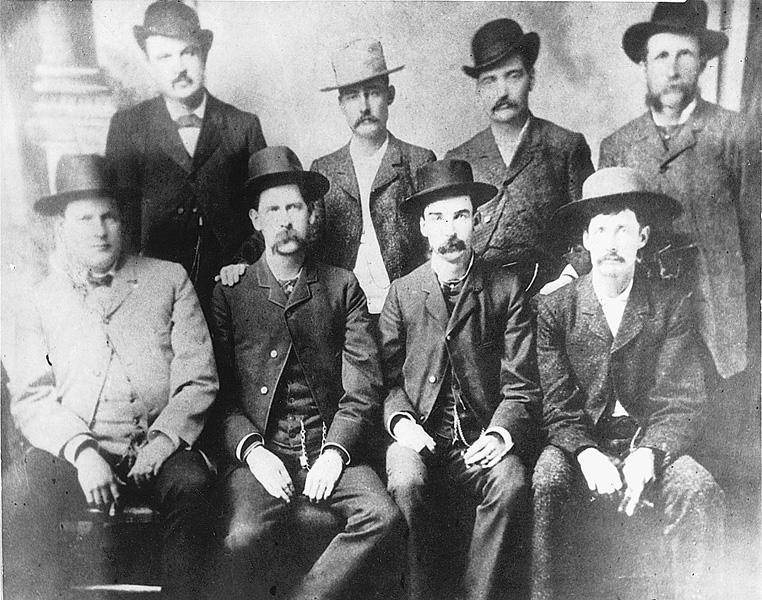

The city’s fire truck arrived on the scene quickly, but there was no water. Dodge City had no water-works system, and most of the pumps were frozen. A bucket brigade was formed, and City Marshal Bill Tilghman ordered small sheds in the rear of the burning buildings torn down. Volunteers fought the flames with only ladders and water buckets.

Next door to the Cowboy building, the Iowa House, which also held a clothing store and tailor’s shop on the bottom floor, caught fire on the east side, but the building was saved. “Had this building been destroyed,” the Cowboy reported, “the appetite of the fire demon would not have been appeased until every building in the Iowa House block had been swallowed up.”

On the east side of the grocery, a dry-goods store was destroyed. Morris Collar’s “hardware store and general curiosity shop” lost most of its stock, valued at $20,000, and the tin shop/hardware store owned by Charlie Shields “went to kingdom come in a hurry, with most of the stock.” Shields had no insurance, and estimated his losses at $1,000.

“It was a miracle that the fire did not extend outside the block it burned,” the Dodge City Democrat reported.

What saved the rest of the town, apparently, was a brick store erected by Jacob Collar. As the Cowboy, in the journalistic fashion of the period, reported: “Now here is where the virtue of brick is demonstrated. . . . The brick wall was too much for Mr. Fire. His stomach couldn’t digest the brick and he quit his infernal deviltry right then and there.”

South of the railroad tracks, the warehouses owned by Robert M. Wright and Morris Collar were destroyed, but the York, Parker, Draper warehouse was saved. Eight buildings had been lost. Robert M. Wright, in his 1913 book Dodge City: The Cowboy Capital, estimated the city’s losses at $60,000, with only $25,000 covered by insurance.

After the fire, the safe was taken from the ruins of Perry Wilden’s store and opened. Surprisingly, none of the contents had been damaged. Reaction to the fire differed. The Cowboy, in its January 24 editions, reported: “Nobody is sulking. The big fire won’t hurt.”

But the Dodge City Democrat took a hard-line stance: “The fire on last Sunday afternoon should be a warning to our city,” the newspaper stated in its January 24 edition, “and preparations made to more affectually fight the flames.” Unfortunately for Dodge City, no one listened to the Democrat’s warning.

The second, and most serious, of the 1885 fires started on the still, damp night of November 27 when “the terrible disaster of last January was to be repeated,” the Dodge City Times reported, “and another section of the city’s business center laid in desolate waste.”

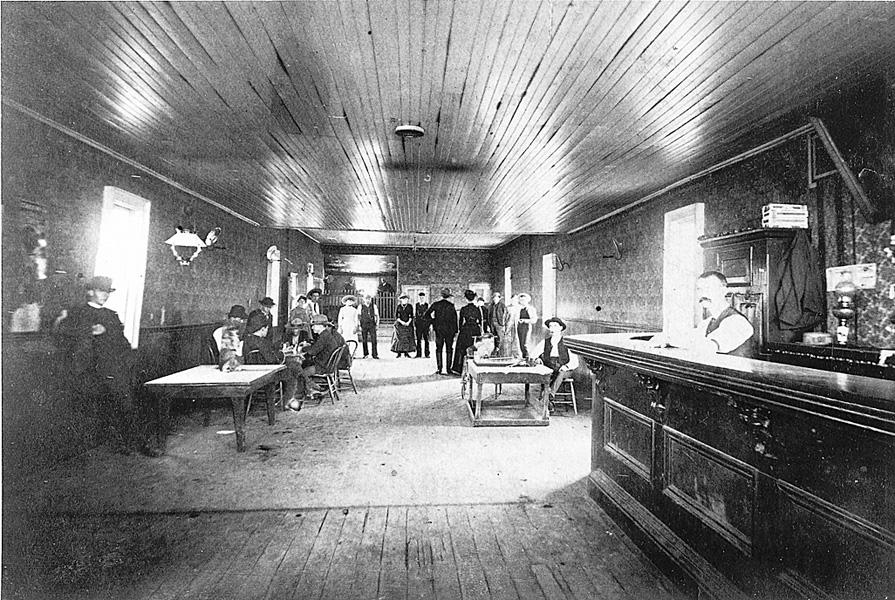

Ten months after the first fire, Dodge City had rebuilt, but Robert Wright’s store remained the only brick building. In fact, the Wright & Company General Outfitting Store was called the “Brick Store” because it stood out among the frame structures. While standing in front of a barber shop, John Koch thought he smelled something burning. He entered another building and reported his suspicions. Someone went upstairs, came down and said there was a fire, but it looked like it had been put out.

It hadn’t.

At 7:00 p.m., the cry of “Fire!” rang out. A coal-oil lamp in an upstairs room at the Junction saloon on Front Street, two doors west of First Avenue, was suspected of exploding or breaking from a fall. The flames spread rapidly, and men, women and children crowded Front and Chestnut Streets, each resident, “with a dread feeling of the terrible disaster fire brings to a frame town,” the Globe Live Stock Journal reported.

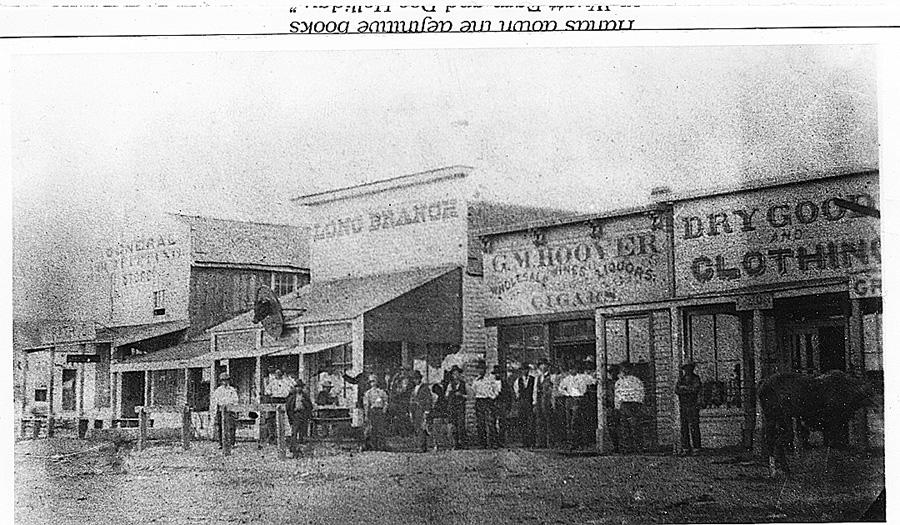

People worked together. “The question was not asked, ‘do you keep a saloon or preach the gospel,’ but let me help you save your property,” the Journal reported. The newspaper went on to laud the work of women. “Women are not weak, [dependent] creatures at a fire, some of them rank at captain.” Men carried buckets of water and spread wet blankets on nearby roofs, but the Front Street block was lost. Among those “land marks” destroyed: Dog Kelley’s Opera House; the Long Branch saloon; Charles Heinz’s Delmonico restaurant; York, Parker, Draper Mercantile Company; F.C. Zimmermann’s Hardware Store; and even Robert Wright’s “Brick Store.”

The brick couldn’t withstand the intense heat from the Webster and Bond drug store, and the contents of Wright’s store ignited. After removing as much merchandise as possible safely, Wright told bystanders to help themselves. “By an over sight [sic],” the Journal reported, “some awful good whiskey was allowed to burn up.”

One block north of Front Street, at the Journal offices at Chestnut Street and First Avenue, City Marshal Tilghman arrived with a ladder and helped move everything out of the second-floor offices except the presses and safe.

Buildings along Chestnut Street were scorched by heat and damaged by water. The next morning, salt, spread over the roofs as fire protection, gave the appearance of a light snowfall. Losses could have been much worse. “The only thing that saved a large part of town was the absence of any wind,” the Journal reported.

In all, 14 businesses had been destroyed, with losses estimated at $150,000. York, Parker, Draper Mercantile cited $20,000 in damages, and Zimmermann’s losses totaled $8,000. Wright estimated his damages at $75,000, or $20,000 over his insurance coverage. Yet the only reported injury was to John Baumann, who suffered a cut and bruised hand, although the Times noted that “fatigue and poor whiskey did a good many boys up.”

“We are slightly disfigured but still in the right as the great commercial point of Western Kansas,” the Journal stated. But the editors were a little miffed at a few thefts: “Somebody has got four new blankets, water bucket, fire shovel and some books belonging to this office.” The Times also condemned the looting: “A man who would steal under such circumstances ought to be stretched in stocks and slowly kicked to death by grasshoppers.”

Once again, Dodge City rebuilt from the ashes.

Robert Wright built a temporary frame building alongside his brick ruins. F.C. Zimmermann took his losses “with his usual good grace,” and the Delmonico Restaurant reopened at a vacated schoolhouse. York, Parker, Draper set up a temporary mercantile south of the railroad tracks, and the Long Branch built a temporary structure over its ashes. “Not a single murmur has been heard to escape from the lips of any of the sufferers of the late fire,” the Cowboy said. “One hundred and fifty thousand dollars went to glory at that time and yet nobody cares a cuspidor about it.”

Reported the Journal: “Everybody will rebuild with brick.” But while residents were still sifting through the ashes, the third fire broke out 10 days later.

“MORE FIRE,” the Times headline declared December 10. “THE RED DEVIL AT WORK.”

Around 11:00 p.m. December 7, a “sporting” girl called “Sawed-off” sent a “boot black” to build a fire in her house on Chestnut Street. The boy filled the stove with kindling, coal and coal oil, lit it, and left the house.

Around midnight, W.J. Van Horn walked by the house and saw fire coming out of the roof beside the chimney. He banged on the door and when there was no answer, opened the door to see the flames. It was too hot to enter the house, and the fire soon spread to neighboring structures.

Volunteers tried to pull the house next door into the streets with ropes, but the building caught fire. Two doors from the “sporting house,” firefighters placed 150 pounds of gunpowder inside Dutch Jake’s house with hopes that the subsequent explosion would blow the house to pieces and create sort of a fire break. The explosion, however, only blew the roof off the house.

The spreading flames soon became so hot that part of each bucket had to be poured on the firefighters.

The conflagration lasted only an hour, but it destroyed two-thirds of the Chestnut Street block: the Bee Hive dry-goods store and Kansas Cowboy offices (which had been burned in the January fire) on the west end; the Odd Fellows Hall and Globe Live Stock Journal offices to the east.

Said the Times, “It is mighty risky to take an insurance risk in Dodge.”

After this fire, bricks were in great demand. The burned district, the Journal reported, “will be rebuilt in the spring with brick buildings, and as near as can be made fireproof.”

Enough was enough. “It might be a cheap investment to vote bonds to establish water works in this city,” the Journal commented the day after the fire. The paper went on to warn, “Be careful about fires. There are several more blocks in town that will go if a fire once gets a start in them.”

This time, Dodge City paid heed. Brick buildings went up and down Front Street and throughout the business district, replacing the false-front frame structures. Downtown Dodge today is dominated by the old brick structures built to quell the “red devil.” In 1886, the city council finally passed an ordinance giving financial support to the fire department. A city water-works system was also established that year, complete with six hydrants in different parts of the city. First tested in late January 1887, the system was met with approval. The Journal reported, “With this excellent system of water-works, and with our three hose companies and hook and ladder company, which are in constant training, Dodge City can defy the fire fiend, in the future.”

That “constant training” paid off for the R.M. Wright Hose Team at the Annual Fireman’s Tournament in Denver, Colorado, in 1887. Eleven teammates pulled a hose cart 450 feet, where two other members pulled 100 feet of hose to a hydrant, and the last two members sent a stream of water at least 20 feet. The team recorded a time of 31 4/5 seconds, a world record, and took home $800 and the silver Fireman’s trumpet.

Dodge City suffered other fires, of course, including an August 1886 blaze that raged through the block closest to the railroad station. A flour mill was destroyed in 1890, and the Opera House burned in 1912. But nothing ever equaled the three fires of 1885, perhaps because the infernos had taught the citizens some costly lessons.

Three such fires might turn many frontier cities into ghost towns, but the Queen of Cowtowns survived. “The 1885 fires, along with the loss of the cattle trade and the local cattle losses that resulted from the blizzards in January, dealt Dodge a staggering blow,” says Noel Ary, director of the Kansas Heritage Center in Dodge City. “I think it is amazing that the town survived, but it did, and very well.”

“Bred devUSINESS HEART OF OUR TOWN.”

For residents of Dodge City, Kansas, the news seemed all too familiar. The conflagration of November 27 was the second major fire to strike the business district in the Queen of Cowtowns (the first in January), and there was more smoke on the horizon. Less than a week after the Journal’s coverage of the second fire, the “fiend” would struck again.

Like many Western frontier towns, most of them tinderboxes by today’s standards, Dodge City had witnessed its share of fires, common in rows of frame buildings. But early outbreaks had been put out quickly by volunteers, and until 1885, Dodge City had not witnessed any fires that had cost insurance companies. That changed on January 18—ironically, the day after the Kansas Cowboy commented on the lack of damaging fires in the city. The subsequent fires of November 27 and December 7, as well as two smaller fires in 1886, would result in few injuries—and apparently no deaths—but would literally change the face of the town’s business district.

On the afternoon of Sunday, January 18, 1885, a fire broke out in the cellar of Perry Wilden’s grocery store on Front Street between Second and Third Avenues. Flames shot from the windows, and before long, the Union restaurant, next door to Wilden’s on the west side, ignited. The Kansas Cowboy said that the restaurant “ended in smoke at the drop of the hat.” Editors of the Cowboy might have regretted the fire report printed the day before. The newspaper, located on the second floor of a building two doors west of Wilden’s, lost a power press and “a large portion” of type.

The city’s fire truck arrived on the scene quickly, but there was no water. Dodge City had no water-works system, and most of the pumps were frozen. A bucket brigade was formed, and City Marshal Bill Tilghman ordered small sheds in the rear of the burning buildings torn down. Volunteers fought the flames with only ladders and water buckets.

Next door to the Cowboy building, the Iowa House, which also held a clothing store and tailor’s shop on the bottom floor, caught fire on the east side, but the building was saved. “Had this building been destroyed,” the Cowboy reported, “the appetite of the fire demon would not have been appeased until every building in the Iowa House block had been swallowed up.”

On the east side of the grocery, a dry-goods store was destroyed. Morris Collar’s “hardware store and general curiosity shop” lost most of its stock, valued at $20,000, and the tin shop/hardware store owned by Charlie Shields “went to kingdom come in a hurry, with most of the stock.” Shields had no insurance, and estimated his losses at $1,000.

“It was a miracle that the fire did not extend outside the block it burned,” the Dodge City Democrat reported.

What saved the rest of the town, apparently, was a brick store erected by Jacob Collar. As the Cowboy, in the journalistic fashion of the period, reported: “Now here is where the virtue of brick is demonstrated. . . . The brick wall was too much for Mr. Fire. His stomach couldn’t digest the brick and he quit his infernal deviltry right then and there.”

South of the railroad tracks, the warehouses owned by Robert M. Wright and Morris Collar were destroyed, but the York, Parker, Draper warehouse was saved. Eight buildings had been lost. Robert M. Wright, in his 1913 book Dodge City: The Cowboy Capital, estimated the city’s losses at $60,000, with only $25,000 covered by insurance.

After the fire, the safe was taken from the ruins of Perry Wilden’s store and opened. Surprisingly, none of the contents had been damaged. Reaction to the fire differed. The Cowboy, in its January 24 editions, reported: “Nobody is sulking. The big fire won’t hurt.”

But the Dodge City Democrat took a hard-line stance: “The fire on last Sunday afternoon should be a warning to our city,” the newspaper stated in its January 24 edition, “and preparations made to more affectually fight the flames.” Unfortunately for Dodge City, no one listened to the Democrat’s warning.

The second, and most serious, of the 1885 fires started on the still, damp night of November 27 when “the terrible disaster of last January was to be repeated,” the Dodge City Times reported, “and another section of the city’s business center laid in desolate waste.”

Ten months after the first fire, Dodge City had rebuilt, but Robert Wright’s store remained the only brick building. In fact, the Wright & Company General Outfitting Store was called the “Brick Store” because it stood out among the frame structures. While standing in front of a barber shop, John Koch thought he smelled something burning. He entered another building and reported his suspicions. Someone went upstairs, came down and said there was a fire, but it looked like it had been put out.

It hadn’t.

At 7:00 p.m., the cry of “Fire!” rang out. A coal-oil lamp in an upstairs room at the Junction saloon on Front Street, two doors west of First Avenue, was suspected of exploding or breaking from a fall. The flames spread rapidly, and men, women and children crowded Front and Chestnut Streets, each resident, “with a dread feeling of the terrible disaster fire brings to a frame town,” the Globe Live Stock Journal reported.

People worked together. “The question was not asked, ‘do you keep a saloon or preach the gospel,’ but let me help you save your property,” the Journal reported. The newspaper went on to laud the work of women. “Women are not weak, [dependent] creatures at a fire, some of them rank at captain.” Men carried buckets of water and spread wet blankets on nearby roofs, but the Front Street block was lost. Among those “land marks” destroyed: Dog Kelley’s Opera House; the Long Branch saloon; Charles Heinz’s Delmonico restaurant; York, Parker, Draper Mercantile Company; F.C. Zimmermann’s Hardware Store; and even Robert Wright’s “Brick Store.”

The brick couldn’t withstand the intense heat from the Webster and Bond drug store, and the contents of Wright’s store ignited. After removing as much merchandise as possible safely, Wright told bystanders to help themselves. “By an over sight [sic],” the Journal reported, “some awful good whiskey was allowed to burn up.”

One block north of Front Street, at the Journal offices at Chestnut Street and First Avenue, City Marshal Tilghman arrived with a ladder and helped move everything out of the second-floor offices except the presses and safe.

Buildings along Chestnut Street were scorched by heat and damaged by water. The next morning, salt, spread over the roofs as fire protection, gave the appearance of a light snowfall. Losses could have been much worse. “The only thing that saved a large part of town was the absence of any wind,” the Journal reported.

In all, 14 businesses had been destroyed, with losses estimated at $150,000. York, Parker, Draper Mercantile cited $20,000 in damages, and Zimmermann’s losses totaled $8,000. Wright estimated his damages at $75,000, or $20,000 over his insurance coverage. Yet the only reported injury was to John Baumann, who suffered a cut and bruised hand, although the Times noted that “fatigue and poor whiskey did a good many boys up.”

“We are slightly disfigured but still in the right as the great commercial point of Western Kansas,” the Journal stated. But the editors were a little miffed at a few thefts: “Somebody has got four new blankets, water bucket, fire shovel and some books belonging to this office.” The Times also condemned the looting: “A man who would steal under such circumstances ought to be stretched in stocks and slowly kicked to death by grasshoppers.”

Once again, Dodge City rebuilt from the ashes.

Robert Wright built a temporary frame building alongside his brick ruins. F.C. Zimmermann took his losses “with his usual good grace,” and the Delmonico Restaurant reopened at a vacated schoolhouse. York, Parker, Draper set up a temporary mercantile south of the railroad tracks, and the Long Branch built a temporary structure over its ashes. “Not a single murmur has been heard to escape from the lips of any of the sufferers of the late fire,” the Cowboy said. “One hundred and fifty thousand dollars went to glory at that time and yet nobody cares a cuspidor about it.”

Reported the Journal: “Everybody will rebuild with brick.” But while residents were still sifting through the ashes, the third fire broke out 10 days later.

“MORE FIRE,” the Times headline declared December 10. “THE RED DEVIL AT WORK.”

Around 11:00 p.m. December 7, a “sporting” girl called “Sawed-off” sent a “boot black” to build a fire in her house on Chestnut Street. The boy filled the stove with kindling, coal and coal oil, lit it, and left the house.

Around midnight, W.J. Van Horn walked by the house and saw fire coming out of the roof beside the chimney. He banged on the door and when there was no answer, opened the door to see the flames. It was too hot to enter the house, and the fire soon spread to neighboring structures.

Volunteers tried to pull the house next door into the streets with ropes, but the building caught fire. Two doors from the “sporting house,” firefighters placed 150 pounds of gunpowder inside Dutch Jake’s house with hopes that the subsequent explosion would blow the house to pieces and create sort of a fire break. The explosion, however, only blew the roof off the house.

The spreading flames soon became so hot that part of each bucket had to be poured on the firefighters.

The conflagration lasted only an hour, but it destroyed two-thirds of the Chestnut Street block: the Bee Hive dry-goods store and Kansas Cowboy offices (which had been burned in the January fire) on the west end; the Odd Fellows Hall and Globe Live Stock Journal offices to the east.

Said the Times, “It is mighty risky to take an insurance risk in Dodge.”

After this fire, bricks were in great demand. The burned district, the Journal reported, “will be rebuilt in the spring with brick buildings, and as near as can be made fireproof.”

Enough was enough. “It might be a cheap investment to vote bonds to establish water works in this city,” the Journal commented the day after the fire. The paper went on to warn, “Be careful about fires. There are several more blocks in town that will go if a fire once gets a start in them.”

This time, Dodge City paid heed. Brick buildings went up and down Front Street and throughout the business district, replacing the false-front frame structures. Downtown Dodge today is dominated by the old brick structures built to quell the “red devil.” In 1886, the city council finally passed an ordinance giving financial support to the fire department. A city water-works system was also established that year, complete with six hydrants in different parts of the city. First tested in late January 1887, the system was met with approval. The Journal reported, “With this excellent system of water-works, and with our three hose companies and hook and ladder company, which are in constant training, Dodge City can defy the fire fiend, in the future.”

That “constant training” paid off for the R.M. Wright Hose Team at the Annual Fireman’s Tournament in Denver, Colorado, in 1887. Eleven teammates pulled a hose cart 450 feet, where two other members pulled 100 feet of hose to a hydrant, and the last two members sent a stream of water at least 20 feet. The team recorded a time of 31 4/5 seconds, a world record, and took home $800 and the silver Fireman’s trumpet.

Dodge City suffered other fires, of course, including an August 1886 blaze that raged through the block closest to the railroad station. A flour mill was destroyed in 1890, and the Opera House burned in 1912. But nothing ever equaled the three fires of 1885, perhaps because the infernos had taught the citizens some costly lessons.

Three such fires might turn many frontier cities into ghost towns, but the Queen of Cowtowns survived. “The 1885 fires, along with the loss of the cattle trade and the local cattle losses that resulted from the blizzards in January, dealt Dodge a staggering blow,” says Noel Ary, director of the Kansas Heritage Center in Dodge City. “I think it is amazing that the town survived, but it did, and very well.”

JOHNNY BOGGS is a regular contributor to True West, Wild West, Persimmon Hill, Santa Fean, and CBoy’s Life, and in addition, writes for many newspapers across the country. He lives in Santa Fe.

Photo Gallery

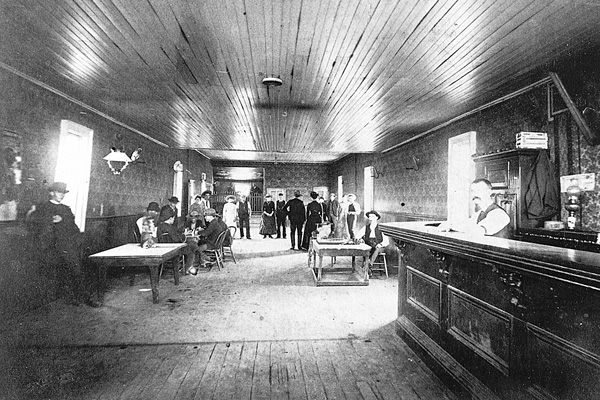

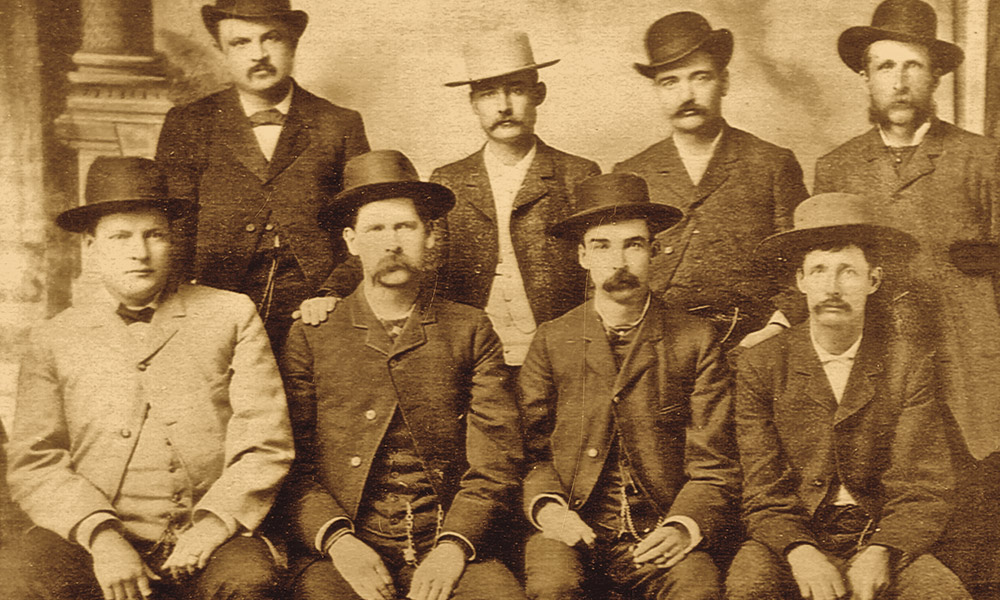

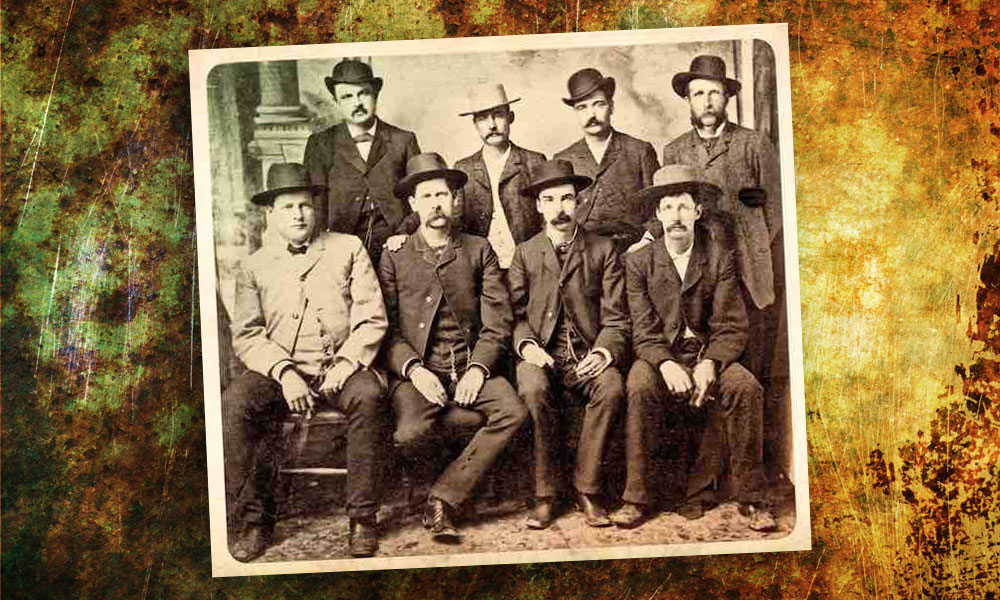

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

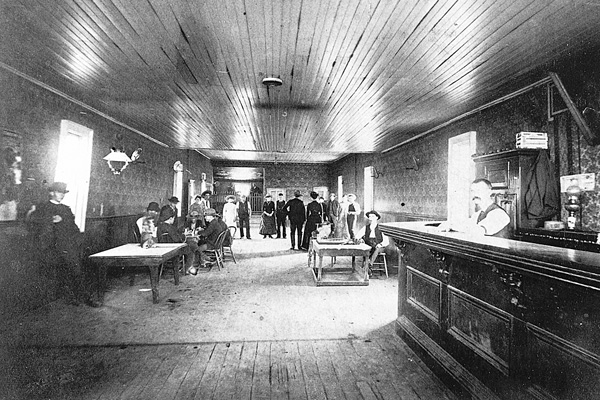

– Courtesy of Boot Hill Museum, Inc., Dodge City, Kansas –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –