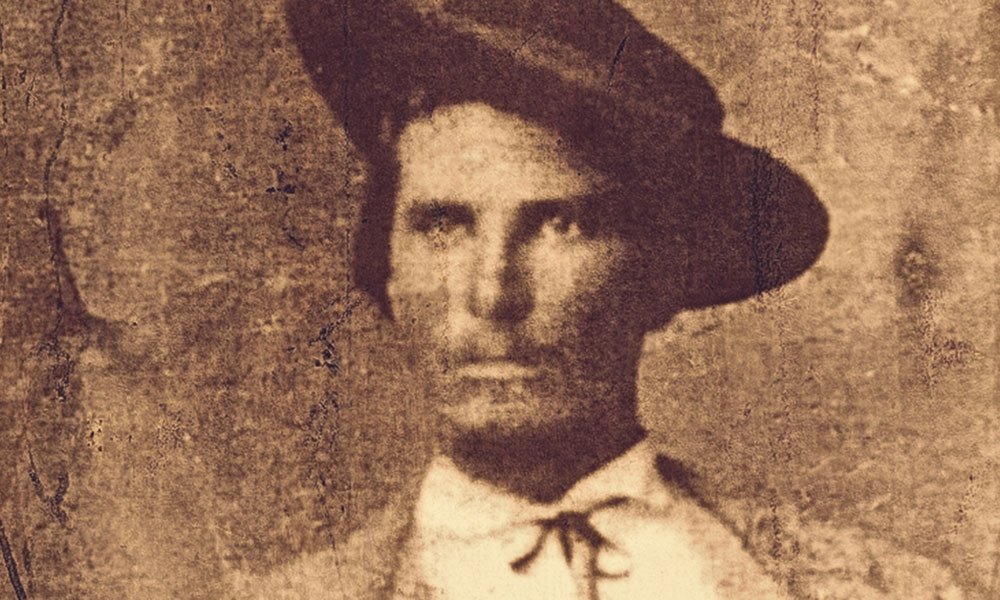

— Courtesy of Sedona Heritage Museum, Sedona, Arizona —

With his grizzled beard, 6-foot-4-inch frame, and paws “hard as Malpais boulders,” Jesse Jefferson “Bear” Howard resembled the animals he trapped well into his 80s. This larger-than-life character became part of Arizona folklore long before his death at age 93.

Born in Illinois in 1817, Howard supplied game to mining camps of the forty-niners after fighting under Sam Houston in the Mexican-American War, during which he was wounded. He carried that bullet in his shoulder for

54 years. “It rattles around my back,” he once complained, “whenever my horse gets out of a walk.” Having mortally shot a Mexican sheepherder during a dispute over pastureland in 1879, this horse breeder fled northern California. To his credit, Howard, who only meant to scare the Mexican, had turned himself in. The jail keeper, an acquaintance of his, left the cell unlocked and provided a horse for his escape. According to a different version of the story, Howard’s daughter baked a file into a “birthday cake” for her father. Indians had abducted her and her brother as youngsters from Howard’s San Jose homestead. Intercepting and battling the marauders, he’d retrieved his children from a cactus patch where they’d been left.

A wanted man, Howard, after changing his name, squatted hidden in a one-room sandstone cabin he built in Oak Creek Canyon, a red-rock refuge in northern Arizona, near today’s Sedona. In his early 60s, he wed the widow Elizabeth James, but that union lasted only three months—his new wife didn’t like Howard’s smelly hounds lying around the house, and he gave away her cattle to people in need. Undeterred, he chased bears, elk, deer, mountain lions and antelope in the Territory, selling game to railroad crews and lumbermen in Flagstaff, then the largest town on the line connecting Albuquerque and the West Coast. Bear meat—grizzly and black—sold over the counter, just like prime rib. Together with the official bounty, a bear’s meat, hide and tallow could fetch $50, ten times a laborer’s daily wage, some of which Howard spent on the occasional toot. By July 4, 1885, he’d already killed 12 bears for the season. Along Oak Creek, he also again bred horses and mules and at 69 still mastered the meanest broncos. The snow on the rim could get so deep that he sometimes rode his horse right over the fence tops.

His strength allegedly grew as he aged. Described as “all molars,” he could “whip just about anyone” even in his twilight years. The stories, inflated, outgrew the man. But like the extinction of Arizona’s grizzlies he so lustily aided, Bear’s end in 1910 marked that of an era.

For a few years, Michael Engelhard lived in Flagstaff, Arizona. As a former Grand Canyon river guide he feels an affinity with historical woodsmen—and women—such as “Bear” Howard.