— True West Archives —

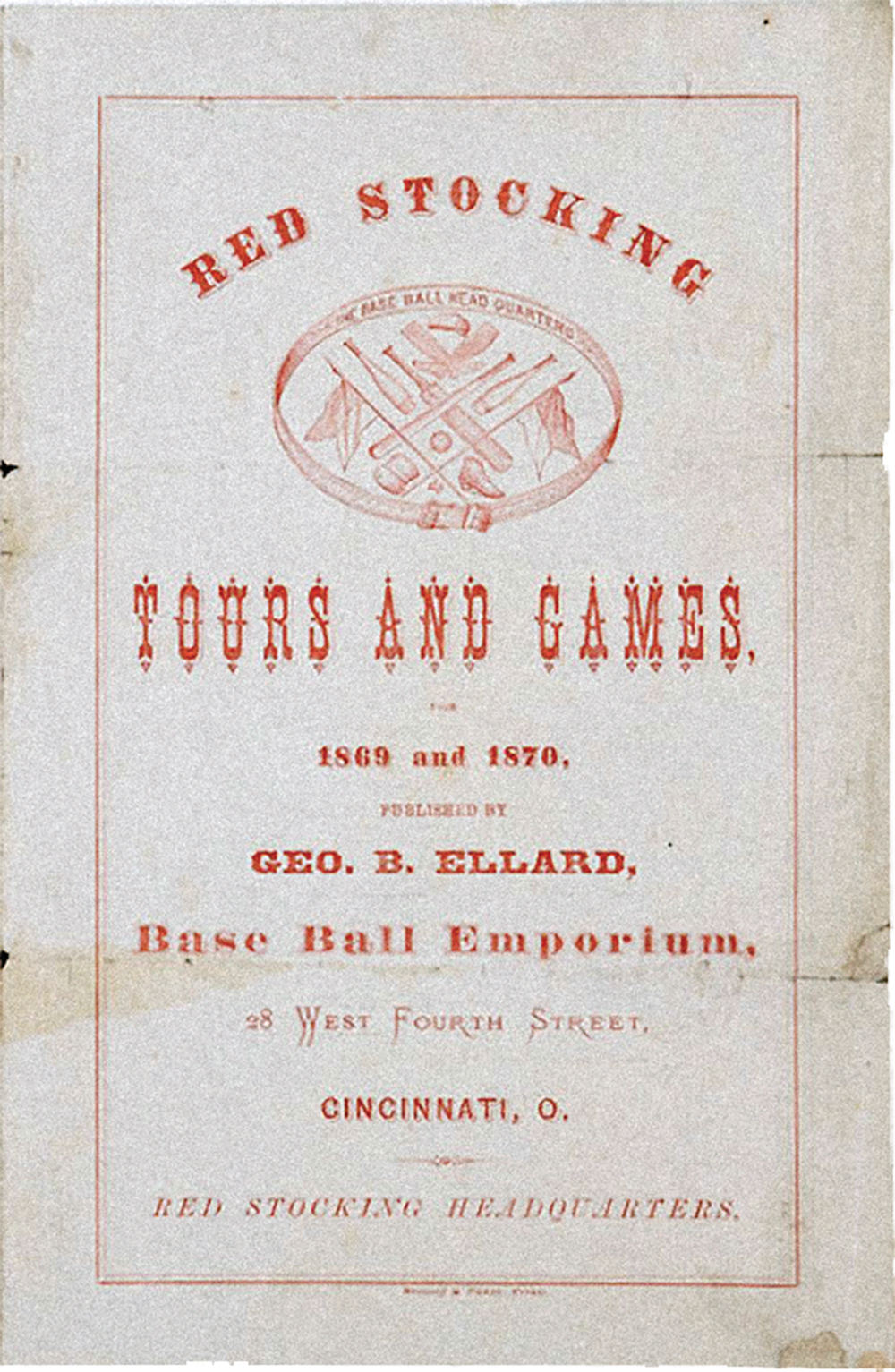

Two sesquicentennial anniversaries in 2019 will commemorate landmark events in the history of the American West. When gold and silver spikes were gently tapped into place in a ceremonial laurelwood rail tie at Promontory Summit in Utah Territory to symbolize the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869, it opened the West as never before. Earlier in the year, the Red Stockings of Cincinnati became the first all-salaried, professional team in the fledgling sport of baseball. Undefeated as the year progressed, the Red Stockings rode these rails in mid-September to introduce professional ball beyond the Mississippi. The West offered opportunity and adventure, attracting people from around the world who flocked to the California gold rush of ’49 and the Comstock silver lode in ’59. Now, in 1869, these professionals came west to demonstrate their wealth of baseball riches to overmatched but eager ball clubs with a hankering to be part of the Red Stockings’ historic season.

— Courtesy Heritage Auctions —

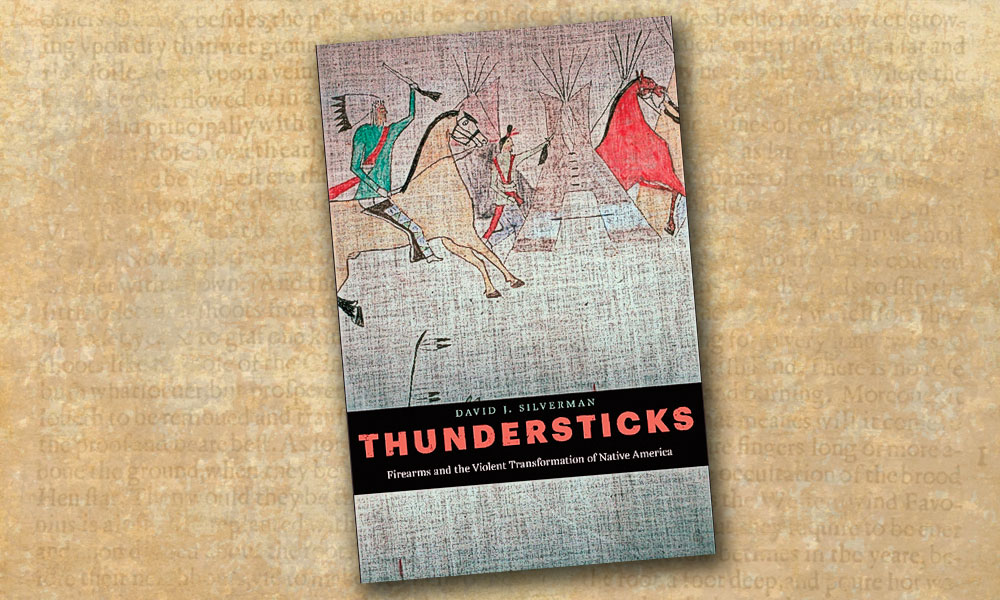

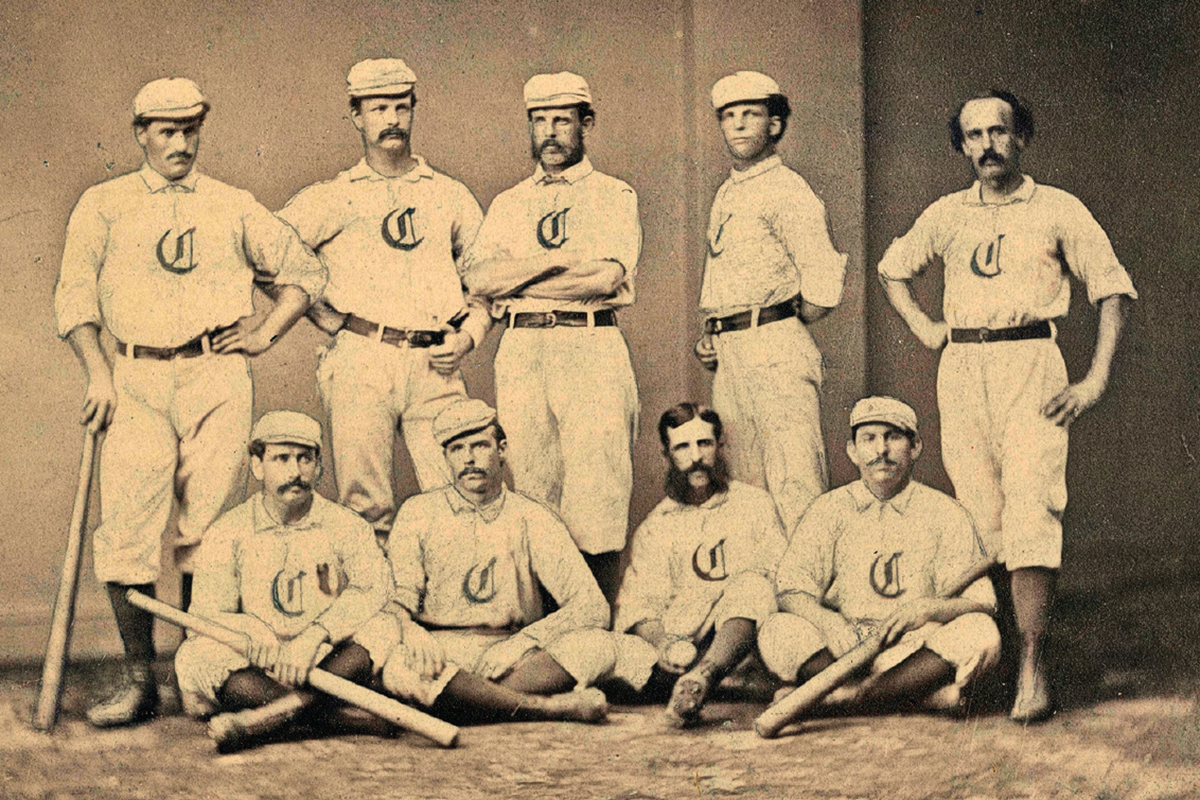

There was never a team like the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings. They attracted an array of astonishing baseball talent that registered the only undefeated season in professional baseball history. Their centerfielder/manager, Harry Wright was an astute baseball mind, inventing now well-accepted teamwork techniques, such as players calling for fly balls and backing each other up in the field, using substitute pitchers to “relieve” starting hurlers and repeatedly practicing the sport to achieve perfection. His brother, “Smiling George,” had a 1,000-watt grin of pearly whites that matched the star power of his game. He was the first real superstar of the sport, a shortstop with tremendous range and fearsome hitting prowess. Bushy side-whiskered Asa Brainard was their unmatched pitcher, throwing an array of speedballs and spinners that baffled hitters. His nickname, “Ace,” became synonymous with any team’s star pitcher. With a solid cast of support, the Red Stockings were unbeatable as they took on the powers of organized baseball in the East. The game was very different than the version played today. Pitchers threw the ball underhand and there wasn’t a glove to be found, leading to black-and-blue hands or sometimes broken fingers. But the sport captivated much of the country.

— Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections —

Baseball’s First Western Team

As Easterners joined the masses flooding into San Francisco to find gold in 1849, a few brought an enthusiasm for “New York” baseball as outlined in the Knickerbocker Rules of 1845. In early 1851, the local newspapers were reporting on baseball games being played on the Plaza in San Francisco, many of the participants thought to be transplants of the New York Knickerbocker Base Ball Club. In 1859, the first organized team on the Pacific Coast, the San Francisco Eagles, was established. The next February, in San Francisco they played to a 33-33 tie with the Red Rovers of Sacramento. In September, the Eagles traveled to Sacramento in a rematch for the state title, emerging victorious 31-17. In a few years, the Eagles organization had grown such that with the overflow they formed a new club, the Pacifics. Both became premier teams among more than a dozen that organized in the Bay Area. The sport was invigorating to watch and spectators might even shoot their six-guns when excited. With gamblers betting on their favorite team, it’s said it was not uncommon to have enthusiastic supporters fire into the air to shake the concentration of batters taking swings or to rattle fielders preparing to catch the ball.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Taking the Train West

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in May 1869 was a game-changing moment in the history of the West. The 1,900-mile journey from Omaha, Nebraska, to Sacramento, California, which previously had taken five months by wagon train, now took five days. Granted, each mile on the train was a bone-jarring experience as it clattered over the rails, especially at top speeds of 60 miles per hour. Expanded markets and cheaper channels to distribute products were major economic benefits of the rail line. The Red Stockings saw their marketing possibilities immediately and scheduled a trip west to showcase their talents to a paying audience.

Up until that point, to the Red Stockings “going west” meant traveling to play teams in Chicago. Beyond the Mississippi River was something they had only read about in headlines touting gold strikes or battles with Indians. In mid-September they began their westward adventure. Out the windows of their Pullman railcars they saw the expansive Western prairies and majestic mountains. Buffalo and antelope were both new to them, at once unusual and inviting for target practice. A number of the ballplayers had brought sidearms, which they employed in shooting at the animals, who were fortunate that the players’ accuracy was better suited for throwing baseballs at targets than hitting them with gunfire. Many years later, George Wright would tell of sleeping on the train with a six-shooter under his pillow, ready for a surprise Indian attack. Of course, they arrived in Sacramento with scalps intact. They took a paddle steamboat into San Francisco and were received warmly on September 23 by an official welcoming committee as well as several thousand curious onlookers.

— True West Archives —

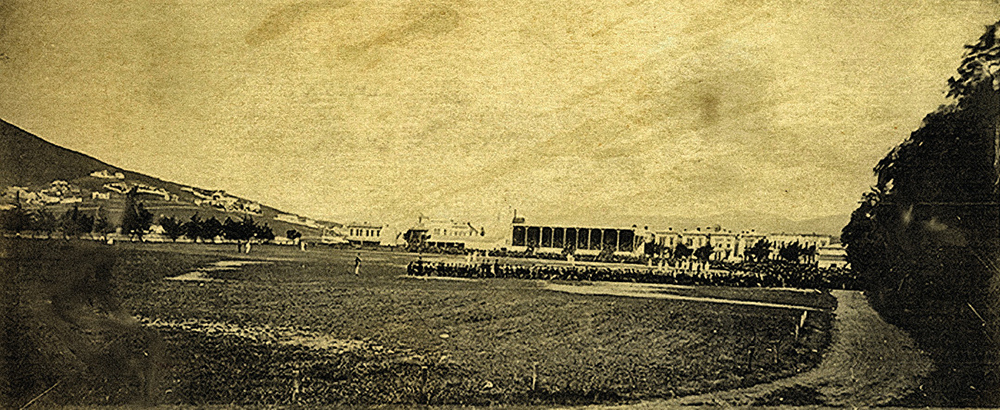

Three local San Francisco amateur clubs—the Eagles, the Pacifics and the Atlantics—had been chosen to represent the city in the upcoming games. All contests were to be played at Recreation Field, a venue for entertainment of all sorts, from circuses to bicycle races. The newspapers proudly noted that special seating was available for one thousand people in the Pavilion at one dollar per person and reserved for ladies and their escorts. First up were the state champion Eagles, the pride of San Francisco and in the midst of their own undefeated season, though only five games long. Cincinnati won convincingly, 35-4. Two days later, the Eagles once again succumbed, this time by an even larger margin of 58-4. Things did not improve when the Pacifics took the field, losing twice to the Red Stockings by 66-4 and 54-5. Finally, the Atlantics were being thrashed so completely at 76-5 after five innings that everyone agreed to mercifully end the game. A final contest was played between a “picked nine” of the best of the three Bay Area teams and Cincinnati, but they faired only slightly better, getting shellacked 46-14.

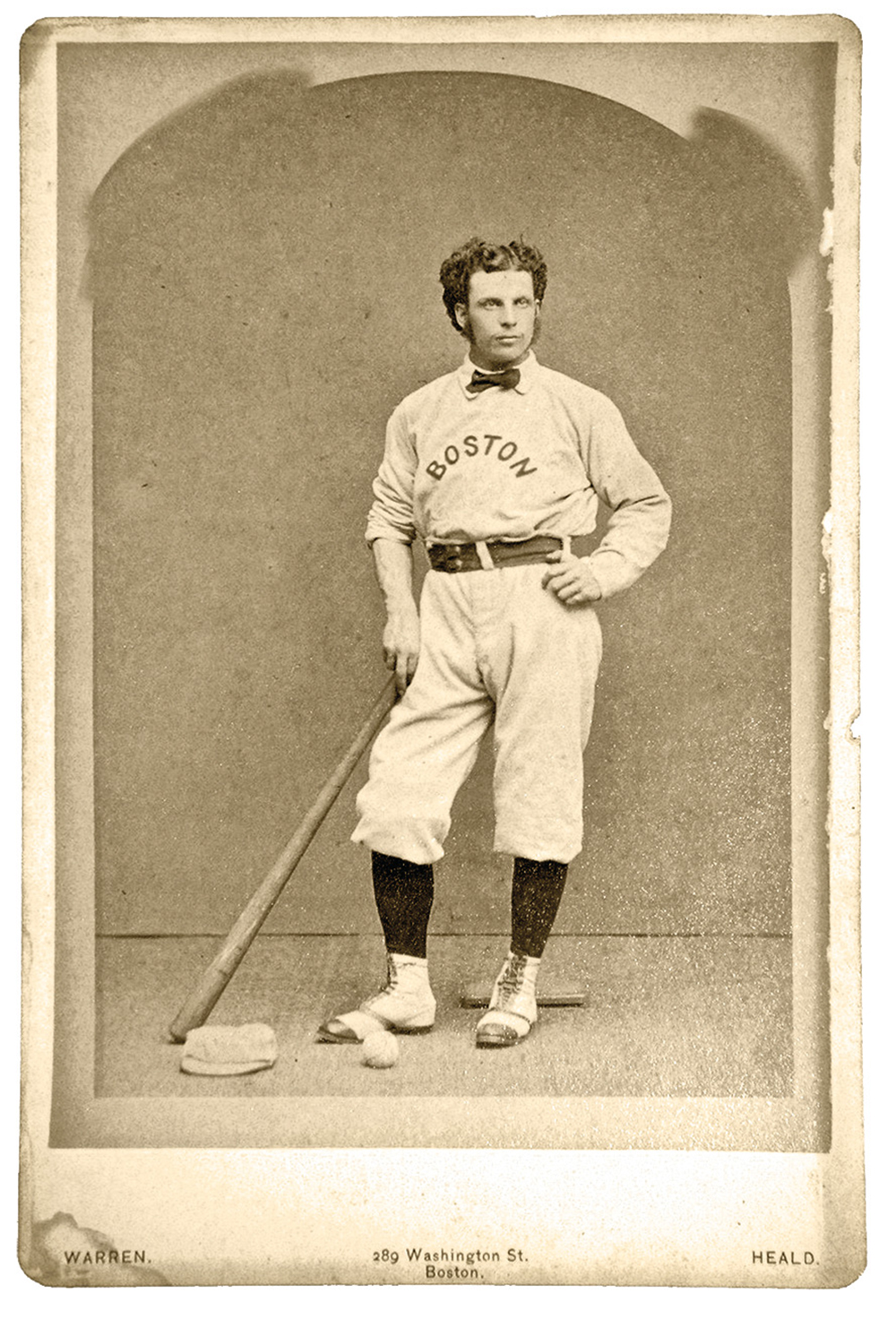

— Courtesy of Jay Sanford —

What was plain to see, besides the sheer muscularity of the visitors that caused one San Francisco newspaper to note the players’ “well-formed calves” that bulged in their bright red hosiery, was that the Red Stockings played a different brand of baseball from the locals. They performed with precise teamwork, backing each other up in case of error. Their pitcher got momentum for his underhand deliveries by taking a step toward home plate, in contrast to the locals who remained stationary, both feet firmly planted, as they delivered the ball. The Bay Area bombers swung for the fences, resulting in lofting “sky balls” to the outfielders; when hitting a grounder they would eye its path and run toward first base almost as an afterthought, usually being thrown out in the process. Even though decimated on the field, the home teams enjoyed the opportunity to play alongside the storied Cincinnati ballclub as it displayed professional baseball to the West. The Red Stockings left for home shortly thereafter, flush with cash from their share of admissions fees. They played a quick game in Sacramento against another picked nine, which they handily won 50-6. Then they left the West, only stopping when they reached Omaha to wallop two more local teams by the scores of 65-1 and 56-3. At season’s end, including exhibitions, they had registered 68 wins and one tie.

Two mining towns in Nevada had high hopes that the Red Stockings would stop there for ballgames, but it didn’t happen. To reach Virginia City or Carson City, each about thirty miles south of the nearest rail stop in Reno, would entail a long, uncomfortable wagon ride for the Easterners, quashing any hopes of a visit. Both towns were disappointed, but they continued to play ball. The allure of instant wealth appealed to miners as inherent risk-takers, but, as noted by a scholar’s study of the times “mining itself was generally tiresome, monotonous, and frustratingly unsuccessful.” Baseball was a welcome distraction, usually accompanied by beer for parched throats and gambling on the outcome, an appealing trifecta for the miners.

— Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections —

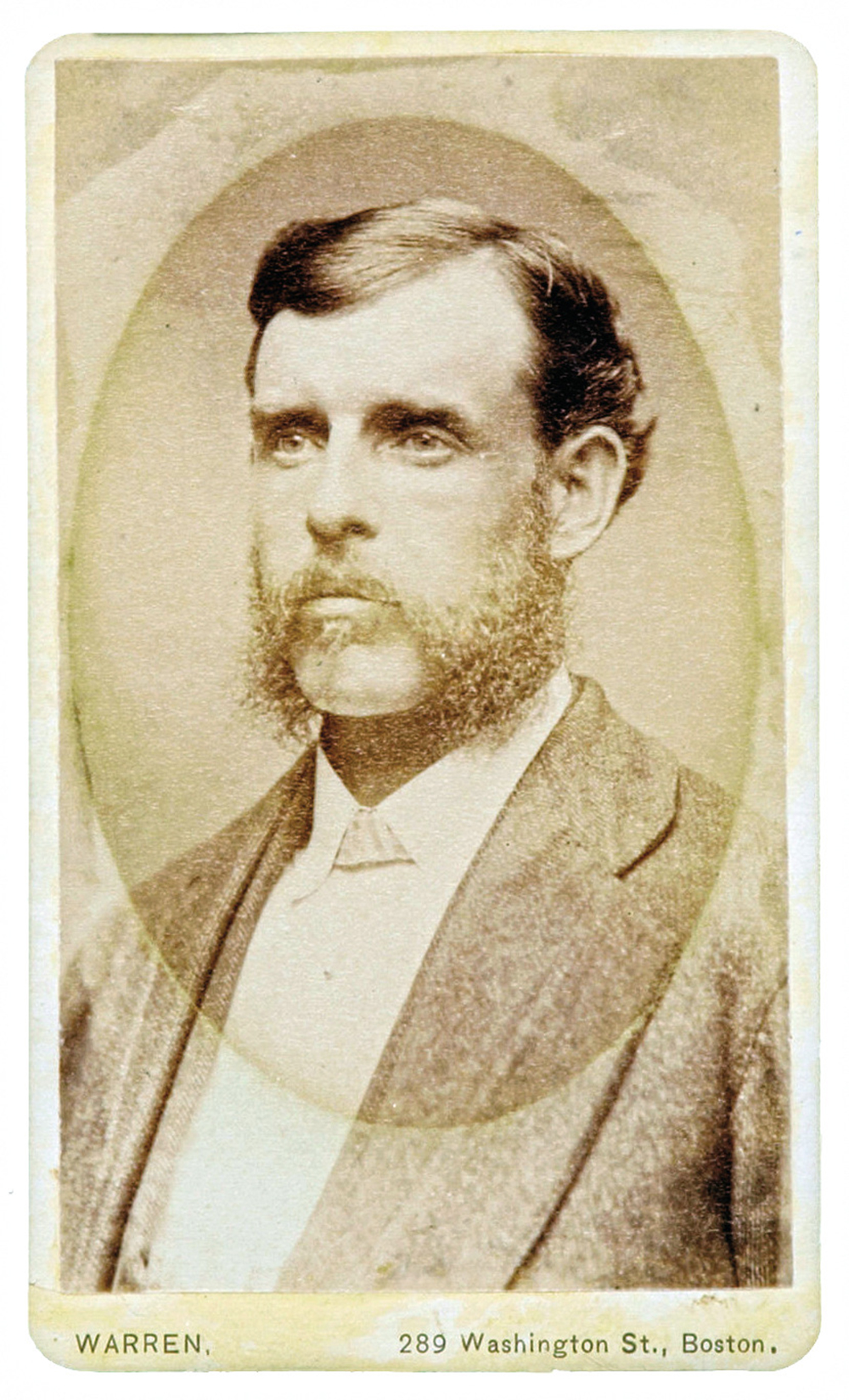

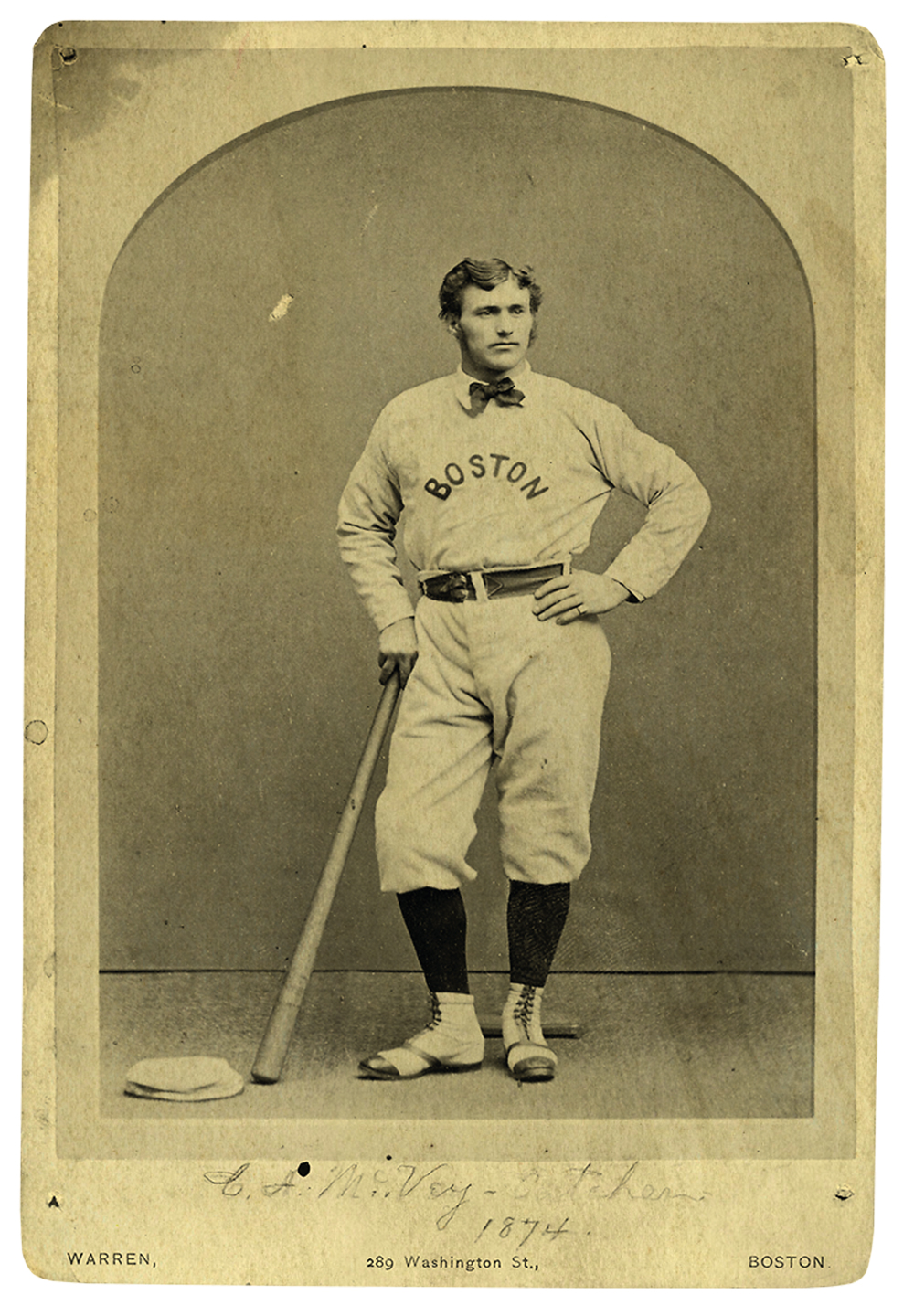

Nineteen-year-old Cal McVey had been part of the Red Stockings trip west in 1869. A strong Iowa farm boy, Cal was a prodigious hitter and the team’s right fielder. When the Red Stockings disbanded at the end of 1870, he followed Harry Wright and two other teammates to form another club in Boston. They wore their red hosiery and called themselves the Boston Red Stockings, becoming the next great professional ballclub. In 1878, Cal returned to Cincinnati as a player/manager and brought his team to San Francisco for exhibitions at the end of the 1879 season, a decade after his initial visit. This time he stayed.

Cal became a baseball version of Johnny Appleseed in California, founding or playing on teams wherever his work took him. Seymour R. Church’s early baseball history Base Ball Vol. I ,1845-1871 (1902) contains an interview with McVey in which he states he captained Oakland’s Bay City team in 1880, moved to Hanford in central California and formed a ballclub which was a consistent winner from 1882-85, then went further south to San Diego in 1887 and organized another successful team before returning to San Francisco. Church thought so highly of McVey as a baseball pioneer that he dedicated his book to him.

— True West Archives —

By the mid-1880s, like the tumbleweed, amateur and semi-pro baseball teams blanketed much of the West. In 1888, the San Francisco Examiner published a poem that was to launch baseball into mainstream American consciousness. It was called Casey at the Bat. By chance, the story of the Mudville Nine was recited that summer on Broadway and it brought down the house, becoming an instant classic. Vigorous debate ensued over who Casey was based on and where Mudville was located. The magic of the piece was that many teams had a Casey, and most could be from Mudville, from mining communities in Nevada to the coalfields of West Virginia, train stops in Nebraska to steel towns in Pennsylvania. Baseball had truly spanned America, linked by steel rails and an addictive passion for the sport, spurred on in the West by the Red Stockings’ visit 150 years ago.

Jeff Orens is a retired business executive with a passion for history. He writes on a broad range of topics, including sports, business and politics. Western tales on these subjects are special favorites.