During the mid-1870s the federal government began using churches to staff the reservations in Arizona. The two most successful converters, the Mormons and Catholics were excluded from this group.

As usual there was considerable overlapping of authority and bickering between civil and military authorities. During periods of grave danger, cooperation was present. When all was quiet, the infighting began again. The Apache were quick to notice this rivalry and took advantage of the situation whenever possible.

Corruption on the part of agents was not uncommon. The system was an open invitation to steal. General George Crook reported one case where an agent on a $2,500 annual salary stayed a year and went home with $50,000.

Following the successful offensive in the Tonto Basin in 1873-1874 and the surrender of more than 2,000 Yavapai, Crook settled them on the reservation at Fort Verde. By and large they were happy, no doubt tending to support the notion that they should be moved to a less suitable location. Some Washington official decided that since the Apache groups had been classified as one tribe, why shouldn’t they all live happily on the same reservation.

There was no more unsuitable place for man or beast could be found than San Carlos. The bureau simply wished to group all the Apache together even if they weren’t all Apache, including the Yavapai, who came from a different language group. Little consideration was given to climate, customs or environment. General Crook objected but to no avail. The Indians were unceremoniously told to pack up and move.

During this period several groups, led by Chunz, Delshay, Chan Deisi and Eskiminzin bolted. A bounty was offered for their heads and all were collected on with the exception of Eskiminzin.

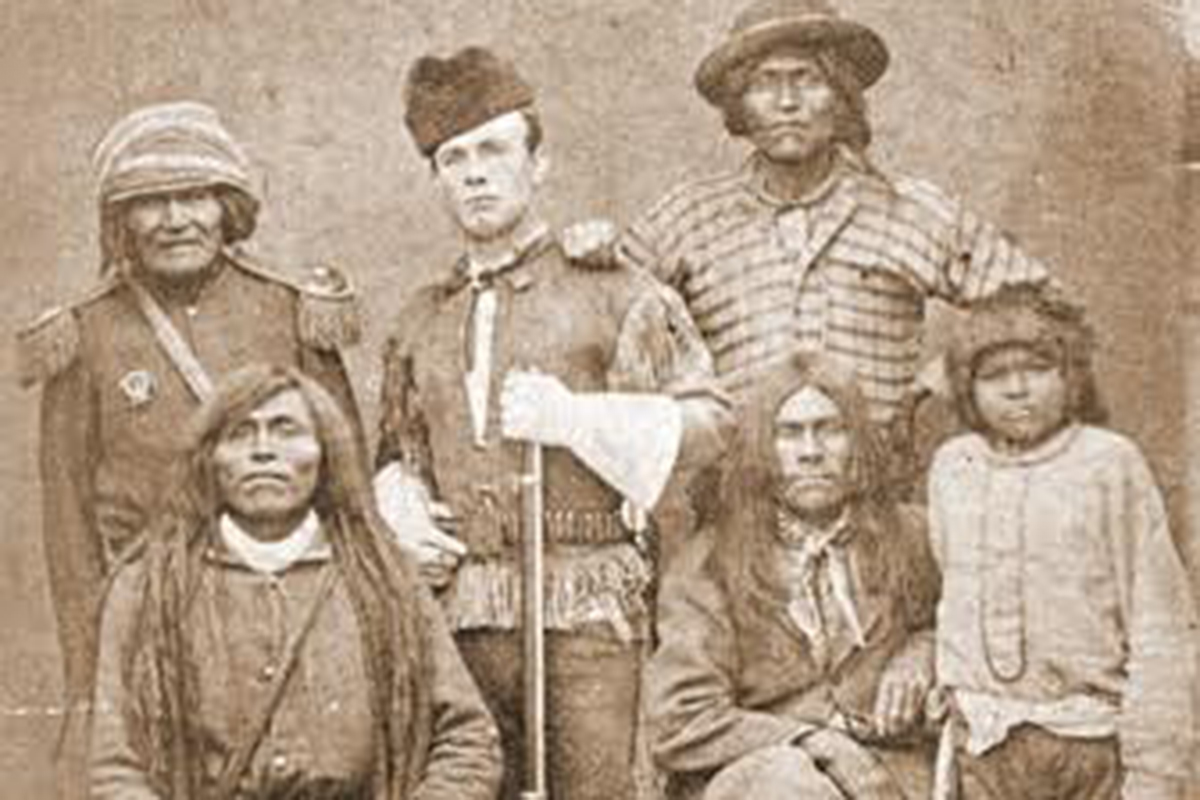

It was to the benefit of the Indians that, at this time, there should appear on the scene a brash, outspoken, twenty-three-year-old man sent by the Dutch Reformed Church. He was not long in making his presence felt.

Considered intractable by the military, whom he never missed an opportunity to criticize, there was no doubt he was cocky and arrogant. On the other hand, he was thoroughly honest and hard-working. He trusted the Apache and they, in turn trusted him. For a time, the Indians at San Carlos were in good hands.

On his first day on the job, the new agent was greeted with a row of heads lined up on the parade field, compliments of Indian bounty hunters. Some of the heads were over two weeks old. If the New York lad was feeling squeamish, he did not let on, but went about his work.

One of his first early tasks was the removal of the Army from the reservation. The military was not eager to comply with his request but in the end, he prevailed. Believing that the Indians would respond better if they were able to govern themselves, he organized a police force of Apache. Inspections were held, the villages were kept clean for health purposes and a judicial system was established among the various groups. A check-out system was used for firearms when game was needed and last but not least the making of the intoxicant tiswin was forbidden. All in all, this was no small deed for a young, eastern dude. His brief stint and influence as Indian Agent were significant indeed but in the end the system would defeat him. Resigning in disgust John Clum headed for the new boom town of Tombstone where he became editor of the Epitaph (after famously saying “every Tombstone needs an Epitaph,”) and mayor of the “Town Too Tough to Die.” He would play a major part in the town’s early and colorful history.

He thought they were capable of self-government and policing themselves and they proved him right.