A little-known Christmas story is that of the time when the generous folks at Nogales, Arizona “adjusted” the Mexican border to accommodate some less-fortunate children in Nogales, Sonora. On December 25th, 1929 part of the U.S. border was moved two blocks north to include the municipal Christmas tree in Nogales, Arizona so that some 3,000 children living in Nogales, Sonora could come to the tree and receive gifts.

A MERRY CHRISTMAS AT FT. YUMA

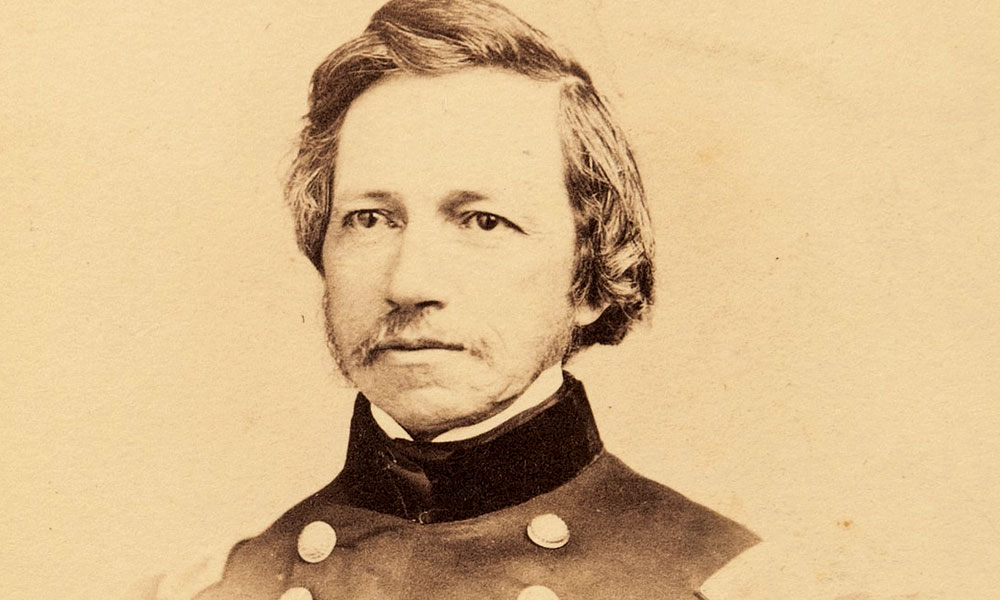

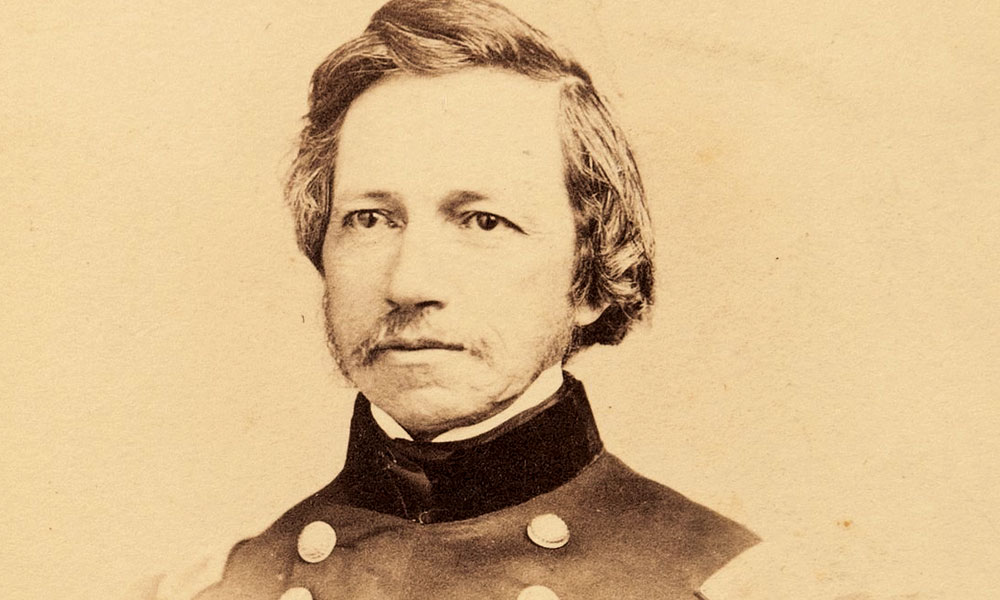

The workhorse among the Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers surveying Arizona during the 1850’s was Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple. He was the steady and sure wheelhorse of J. R. Bartlett’s and Major William Emory’s boundary commissions. The treaty makers had made a number of SNAFU’s when establishing the new 1,500 mile boundary between the United States and Mexico in 1848 and it was up to Engineers like to Whipple to straighten out the mess before hostilities broke out again along the border.

Whipple finished the boundary work on December 10, 1849. Earlier that year Whipple, a thirty-one year old native of Massachusetts had rescued a young Yuma Indian girl who’d been lost in the desert. The girl was nearly dead from exposure, thirst, and hunger. Whipple kindly shared his water and food with the youngster and before she was returned to her village, he presented her with a mirror. It was a simple token of friendship, and something any young girl would cherish.

Two years later Whipple returned to Arizona to survey the Gila River, which at the time marked the boundary between Arizona and Mexico. By December 22 they were some 60 miles upstream from Fort Yuma at the confluence of the Gila and Colorado Rivers. Supplies were running low so Whipple decided to pack up his gear and take his 47-man force to Fort Yuma to spend Christmas.

They arrived at Fort Yuma to find it abandoned. Instead, he was greeted by a force of some 1,500 angry Yuma Indians who were upset because of abuses perpetrated upon them by emigrants passing through to the gold fields of California. On Christmas Eve he learned through an interpreter they planned to attack him and wipe out the soldiers.

Whipple gathered his little force on a hill near where the Yuma Territorial Prison stands today and prepared to make a stand. The next day as the war chiefs gathered their warriors Whipple stood facing them. At that moment a young girl, the one who Whipple had saved two years earlier, stepped forward and spoke to her father, who was one of the chiefs. She pointed out Whipple as the man who saved her life two years before. The tension was broken and a massacre that Christmas day of 1851 was averted thanks to the kindness of Army Topographical Engineer Whipple.

In 1853-54, he mapped the present mainline of the Santa Fe Railroad along the 35th Parallel, West of Albuquerque. His expedition began at Fort Smith, Arkansas west to Albuquerque, and from there to Los Angeles. Traveling with him were two noted assistants, Lt. Joseph C. Ives, who later explored the Colorado River, and Heinrich Baldwin Mollhausen, a German artist, whose later writings about his experience in the American West would earn him the title of “The German Fenimore Cooper.” Many of the artists and scientists on these expeditions were Germans, who had a fascination and wanderlust for the American West.

Whipple rose to the rank of general during the Civil War and was killed by a sniper at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. A year following his death Fort Whipple, Arizona was named in his honor.