James Butler Hickok proved on numerous occasions that he was neither gun nor camera shy, and his attraction to the opposite sex is also well known. But few would have imagined that he might also have been a . . . poet? This possibility came to light in September 1985, when I received a call from an art dealer, then located in San Antonio, Texas, to ask if I would examine a tintype photograph alleged to be Wild Bill, together with an accompanying “poem” thought to have been written by him. Intrigued, I readily agreed, and copies of both items were mailed to me.

James Butler Hickok proved on numerous occasions that he was neither gun nor camera shy, and his attraction to the opposite sex is also well known. But few would have imagined that he might also have been a . . . poet? This possibility came to light in September 1985, when I received a call from an art dealer, then located in San Antonio, Texas, to ask if I would examine a tintype photograph alleged to be Wild Bill, together with an accompanying “poem” thought to have been written by him. Intrigued, I readily agreed, and copies of both items were mailed to me.

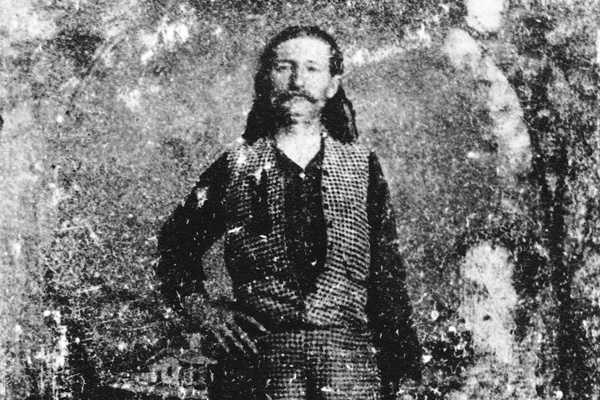

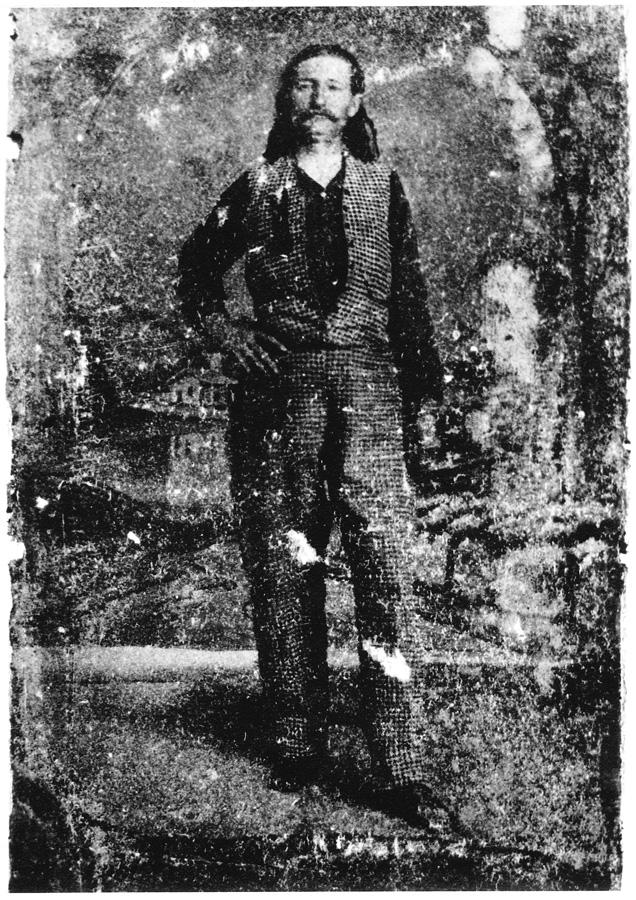

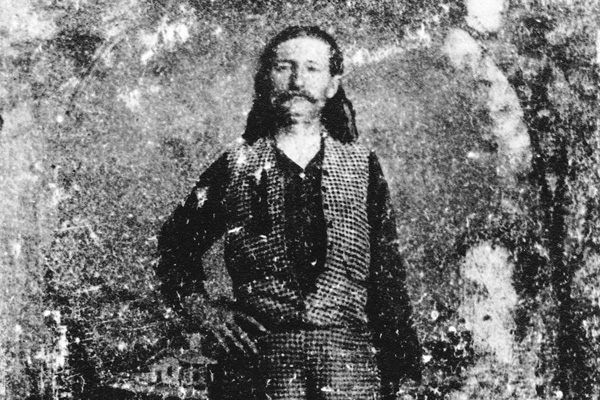

At a glance, the photograph needed little comment, for despite some damage, the image was undoubtedly that of James Butler Hickok. The poem, however, was another matter. My initial reaction was that it might have been written by Hickok, but later I had doubts. Written in pencil, it was discovered inside the leather case that contained the photograph.

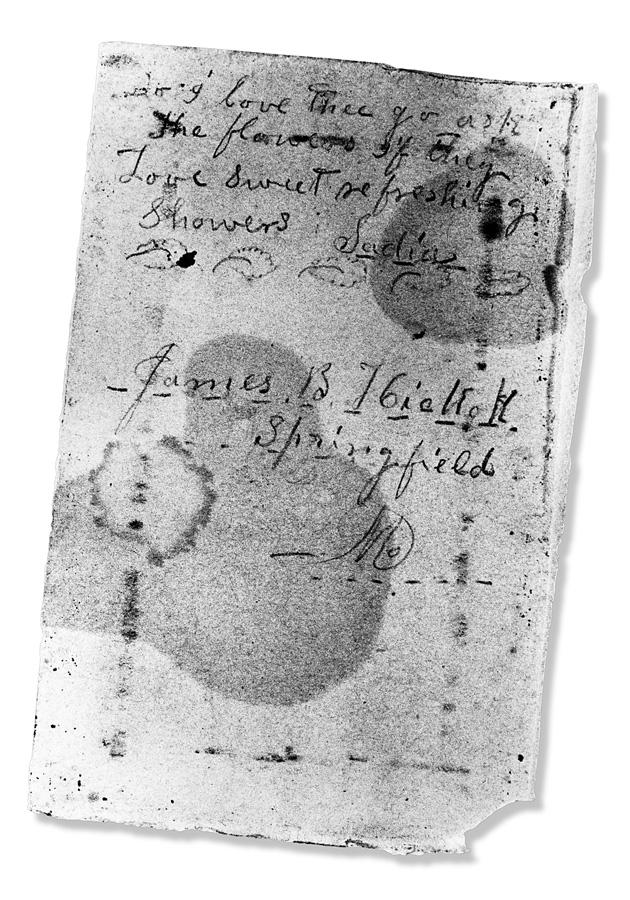

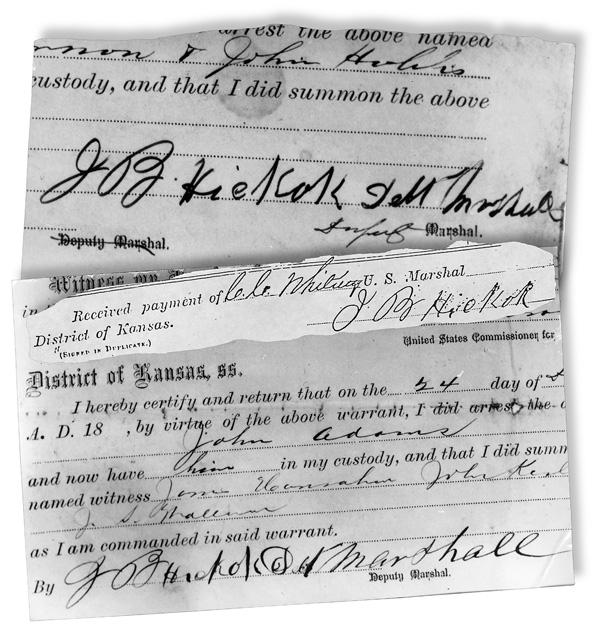

The dealer and I corresponded on the subject, and in a telephone conversation shortly before both items were put up for auction, I said that after some consideration I was not convinced that Hickok actually wrote the poem; the handwriting differed from known specimens, and it was most unusual for Hickok to sign his full name—the only known examples were found in several letters written home from Kansas in the 1850s. All other versions examined are signed “J.B. Hickok.” Despite my reservations, however, I said I would keep an open mind, and suggested that at some point a professional handwriting expert be called in to examine the document. (So far as I know, this has not been done.) Although the poem is undated, a reference to Springfield, Missouri, established where the lady either received it, or the plate was made, and gave me a place to start my search.

Hickok was a familiar figure in Springfield during the Civil War. He was also well known in Rolla and other parts of southwest Missouri and Arkansas, where he served variously as a wagonmaster, provost marshal’s detective, and a government scout and spy. His brother Lorenzo, himself a government wagonmaster, occasionally met up with James either at Springfield or Rolla.

On September 10, 1864, writing from Rolla to his brother Horace at Troy Grove, Illinois, Lorenzo advised him that James had paid him a four-day visit and that “he was going to have his Photograph taken while here but it was stormy all the time[.] Says he will send me some in a few days[.] if he does I will send one Home.” This suggests that James would provide paper prints or cartes de visite size photographs rather than a tintype since Lorenzo refers to some rather than one.

By now, I realized that my efforts to track down both the photographer and the author of the accompanying poem would not be easy. My questions concerning the discovery of the tintype and the poem revealed that they were purchased in 1965 at an unidentified estate sale in Austin, Texas, and they had remained in a private collection until 1985.

A close examination of the tintype has revealed that Hickok wears a watch chain that disappears into a side pocket of his vest or waistcoat. But the most interesting feature, is the appearance of a masonic or other type of ribbon on his breast, surmounted by what seems to be a steer or a buffalo head. Exactly what this is remains a mystery, but perhaps Hickok was showing off his emblem rather than just posing for another portrait.

Some may ask why, at a time when paper prints and glass plates were readily available, would this portrait be a tintype? Despite such advances in technique, tintypes were cheaper and remained popular until the 1940s.

Fortunately, Hickok’s movements for the period 1872-73 are better recorded, which helps us to date this photograph. Following the decision of the Abilene town council on December 13, 1871, that Hickok’s services as City Marshal were no longer required (they were about to ban the cattle trade and all its “evils”), by December 15, Wild Bill had moved to Kansas City where he was to remain for most of the coming year. A search of the local city directories revealed that he was listed as a boarder at the St. Nicholas Hotel, and was a regular visitor to the Marble Hall gambling establishment where he played poker or faro. Then, in July 1872, at the suggestion of his friend Major Frank North, the famed leader of the Pawnee Battalion during the Indian wars, Hickok was approached by the Canadian museum owner Sidney Barnett with an offer to appear as a Master of Ceremonies at Niagara Falls, Ontario, in a “Grand Buffalo Chase.” Featuring local Indians and buffalo, the show took place at Niagara Falls on August 28 and 30.

Back in Kansas City on September 27, soon after, Hickok set course for Springfield, Mo. He may have decided he needed a change, or perhaps he was among a number of gamblers and others deemed undesirable by the town council which ordered Marshal Speers to remove them.

My first task, of course, was to confirm Hickok’s arrival in the city late in 1872. I concluded that he would have traveled there via the Atlantic and Pacific Rail Road link established between Kansas City and Springfield in 1870, but my questions concerning his date of arrival drew a blank. No one had seen any mention of him in the newspapers, and he did not appear in the city directories. I thought this odd, but decided to look anyway. I was, therefore, delighted to find that in the 1873 edition, one “J. B. Hicoh” was listed as a boarder at the St. James Hotel. A librarian, who had been working on the directories as part of a census exercise, told me that Hickok (by now there was no doubt that it was him) must have arrived in the city either late in September or October 1872 in order to qualify for entry in the 1873 directory.

Having established Hickok’s presence at Springfield, I again turned my attention to the vexed question of the “poem” and its relation to Wild Bill. Back in 1985, my misgivings about the alleged Hickok signature were heightened by my reaction to the poem. Still uncertain, I brought up the subject with my friend and co-author, the late Robin May. I asked him if it might have something to do with William Shakespeare. Robin, an expert on the bard, said no, but did suggest that I look at the works of John Godfrey Saxe because something about the poem reminded him of a similar work by Saxe. So, in October 1985, during a visit to the Kansas State Historical Society at Topeka, I enlisted the aid of the ladies in the Society’s library. They soon produced a copy of Saxe’s poem “Do I love Thee?” and a comparison of both poems revealed similarities. Here follows both the version found with the tintype and the last verse of Saxe’s original poem:

Do I love thee go ask

The flowers if they

Love sweet refreshing

Showers.

Sadia

And the Saxe original:

Do I love thee? Ask the flower

If she loves the vernal shower,

Or the kisses of the sun,

Or the dew, when day is done.

As she answers, Yes or No,

Darling! Take my answer so.

Then came the big surprise: “Who was the woman who wrote this?” asked the ladies when they looked at the Hickok version of the poem. I explained that it had been alleged that Hickok himself wrote it. They shook their heads. “That was written by a woman, for it is obviously a feminine hand and the flowery drawings are a definite feminine touch.” Their reaction made a lot of sense, and suggested a fresh interpretation of both the poem and its author. One could easily imagine that Hickok presented the photograph to the lady in question who, in turn, added the verse, and identified Hickok and the place where she acquired it. Before reaching such a conclusion, I had to learn more of the mysterious “Sadia,” and what might have happened to her. Hickok’s relationships with women are legion, and perhaps lovesick Sadia was one of several women who attracted his attention during his period at Springfield. If so, we must again ask who she was. And here we have a problem.

The 1870 census (the closest one available to the 1872-73 period) failed to find any ladies named “Sadie” or “Sadia.” Sadie is, of course, a diminutive of Sally or Sarah. At least two Sarahs figured in Hickok’s earlier life: Sarah McLaughlin, still a child at Troy Grove when he left home in 1856 (and who remembered him vividly into old age), and Sarah Shull, the mistress of David C. McCanles at Rock Creek, Nebraska Territory in 1861. However, I did have one break. In the census there is a reference to a “Mr. James Vaughn,” owner of an unnamed hotel situated close to the St. James Hotel. Among Vaughn’s domestic staff was a 21-year-old girl from Canada named Salina Stubbs. No further reference to her has been found (we checked as far as the 1880s), and it would be a long stretch of the imagination to suggest that she was the mysterious Sadia. Nevertheless, since the consensus of opinion is that the poem was written by a young woman, and given the close proximity of her abode to that of Wild Bill’s, it does suggest a possible connection. But conjecture is not proof, for I suspect that the answer to the riddle of Sadia may yet lie in Texas.

Therefore, we are left with a number of unanswered questions. How did the photograph and poem reach Texas? Did Sadia marry and keep Hickok’s photograph and the poem secret from her husband and family, or did she never marry, yet mourned him? We may never know the answers, but Sadia’s prized possession of Wild Bill’s photograph and her poignant attempt at expressing her feelings for him, remained her secret for almost a century before being rescued from obscurity. Perhaps in time we will also learn more of the lady herself.

Author’s Note: I should like to express my thanks to Fred Kline, the dealer who provided me with prints of the photograph and the poem and gave permission to reproduce them; and to Iris Wylie of the Springfield Public Library who discovered Salina Stubbs and provided me with a great deal of background information.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Bob McCubbin –

– Courtesy of Fred Kline –

– Courtesy the National Archives –

– Courtesy of Bob McCubbin –