It was in March of 1822 that the now-famous advertisement appeared in the Missouri Republican:

It was in March of 1822 that the now-famous advertisement appeared in the Missouri Republican:

TO ENTERPRISING YOUNG MEN. The subscriber wishes to engage one hundred young men to ascend the Missouri River to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years. For particulars, inquire of Major Andrew Henry, near the lead mines in the county of Washington, who will ascend with, and command, the party; or of the subscriber near St. Louis.

General William Ashley and Major Andrew Henry, veterans of the War of 1812 and close friends, had started a new fur company. They incorporated two new ideas. First, they would hire men as free agents, not just employees. Half of the furs their men got would belong to the company while the other half would belong to the individual. This provided incentive. Second, Andrew Henry would take their first brigade of men up the Missouri River to the Three Forks area, build a fort and operate from there. Henry would act as the field commander while Ashley took care of management and supplies.

Almost a hundred men responded to the advertisement, the most notable being a fellow named Jedediah Smith. They left St. Louis on May 8, 1822, and started the slow, hard process of getting a keelboat up the Missouri River.

Keelboats were river craft from 60 to 75 feet long with a 15 to 18-foot beam and a draft of 3 to 4 feet. Their main purpose was to haul supplies. Sometimes the crew poled the boat, pushing it against the current of the river by using long poles poked into the bottom of the river. Other times the crew went on shore and pulled the boat by a towline or cordelle. On a lucky day, they unfurled the sail and let the wind do the work for them. The normal rate of speed was 10 to 15 miles a day. The crew consisted of 20 to 40 men and they were almost always French engagés. These men had lived and worked on rivers all their lives and knew their business. However, once they were away from the water and their boat, they weren’t much good for anything. They were hired to get boats up and down the river and that was all. Other men had to be hired to hunt, trap, trade, scout—and fight.

When Andrew Henry’s party reached the mouth of the Yellowstone River in October, they quickly built a fort which was dubbed Fort Henry. Ashley came up the river with supplies about a month after Henry and then immediately went back to St. Louis. The plan was that he would return the following year with more supplies, collect the furs Henry’s men would trap over the winter and then head back to St. Louis to cash in their profits.

At least that was the plan.

That spring, Ashley advertised again for men to go up the river. Many of them came from “grog Shops and other sinks of degradation” as James Clyman, the unofficial chronicler of the expedition put it, but there were several who would make names for themselves, such as William Sublette, David Jackson and Thomas Fitzpatrick. Ashley got two keelboats for the expedition and he left St. Louis on March 10 with 70 men.

Meanwhile, there were Indian problems upriver. Henry’s men had a fight with the Blackfeet near Smith’s River. Trappers with the Hudson Bay Company, a rival fur company, had two clashes with the Arikaras. In one incident, the Arikaras attacked Cedar Fort which belonged to the Hudson Bay Company. Two Indians were killed and several wounded.

Ashley heard about the Indian problems but he wasn’t about to let that stop him. On May 29, Jedediah Smith showed up on the banks of the river and waved at the keelboats. Ashley met with him. Smith had just ridden across the country from Fort Henry. He told Ashley the trapping had been good that winter but Major Henry needed horses. Ashley hoped they would be able to trade for them with the Arikara Indians. Their villages were just up the river a few days.

Ashley’s brigade reached two of the Arikara villages on May 31, 1823. They were located about 300 yards apart on the apex of a long slope going up on the east side of the Missouri River. An Arikara village looked like a huge prairie dog town. Arikara lodges were large dirt mounds built over frames of heavy timbers. A stockade of willow logs, driftwood, poles of every type and size surrounded the village. Just below the lower village, the river made a horseshoe curve which created a sand bar and an obvious place to land.

The Arikaras appeared on the shore when they saw the two keelboats and waved at them in an apparent gesture of good will. When Ashley went to the shore in a skiff, two of the principal chiefs, Little Soldier and Gray Eyes, met him. Gray Eyes’ son was one of those killed at Cedar Fort and Ashley wasn’t sure what Gray Eyes’ disposition would be. He asked the two about trading and invited them to come on board one of his keelboats. Little Soldier wanted no part of it but Gray Eyes took him up on the offer. Ashley took that as a good sign. On the keelboat, Ashley gave Gray Eyes gifts and told him he had nothing to do with the death of his son. Gray Eyes told Ashley the headmen of the tribe would have to hold a council to discuss trading with the white men. Ashley nodded and waited. That night, Gray Eyes returned to the shore and sent the message to Ashley that trading had been approved.

The next morning, Ashley had his men bring trade goods to the sandy beach on skiffs. The Indians suggested Ashley bring his goods inside the stockade but Ashley declined stating they would do business right there on the beach. The red men talked quietly among themselves and then agreed. Ashley studied them. He still didn’t trust them and let them know he was fully aware of their confrontations with white men lately. The Indians quickly stated they regretted them and wanted to be friends with the white men. So the trading began. Ashley got 20 horses “but in doing this we gave them a fine supply of Powder and ball which on fourth day wee (sic) found out to Sorrow,” Clyman wrote. The white men had to leave their horses on the shore and Ashley left a guard of 40 men with them. Jedediah Smith was left in charge of the shore party and Ashley advised him to keep a sharp watch that night.

The next morning, a storm swept through with strong winds and rain and everybody just sat tight. By that afternoon it cleared up, and The Bear, another leading Arikara man, invited Ashley to his lodge to eat. Ashley accepted and took Edward Rose, a mulatto, as an interpreter. Several chiefs were present and Ashley and Rose were treated well. However, as they were getting ready to leave, Little Soldier took Ashley and Rose aside and warned them the Arikaras planned to attack before they left, if not the keelboats then the shore party guarding the horses. Little Soldier advised Ashley to get his horses to the west side of the river.

Ashley was confused. Were they words of warning or a threat? He had seen Arikara warriors on the west side of the river. Was Little Soldier trying to set him up to have the horses stolen?

That night, Ashley again told Jed Smith to keep an eye out for trouble and then he went to bed in one of the keelboats. Some time after 3:00 a.m., Edward Rose ran out of the Arikara village and down the slope toward Smith’s men yelling that Aaron Stephens, one of their men, had just been killed by the Indians. Apparently, Rose and Stephens had stayed in the village and enjoyed some female company. The Arikara women were not famous for their chastity and sometimes their men used them for profit. Somehow, the amorous escapade of Aaron Stephens went bad and the woman’s male relatives harshly intervened. Or perhaps it had been a trap.

Jed Smith didn’t ask too many questions. He just got his men up and ready. Word was sent to Ashley. It was still dark and they decided they would just do nothing until dawn. “We laid on our arms expecting an attack as there was a continual Hubbub in the village” Clyman wrote. As the false dawn lightened the eastern sky, a lone Indian stepped out from behind the stockade and called to the white men. If the white men would give him a horse, he would bring out the body of Stephens. He told them Stephens’ eyes had been pulled out, his head cut off and his body mangled but the red man would provide all the parts. Jed and his men seethed and didn’t even answer. It had to be a trick.

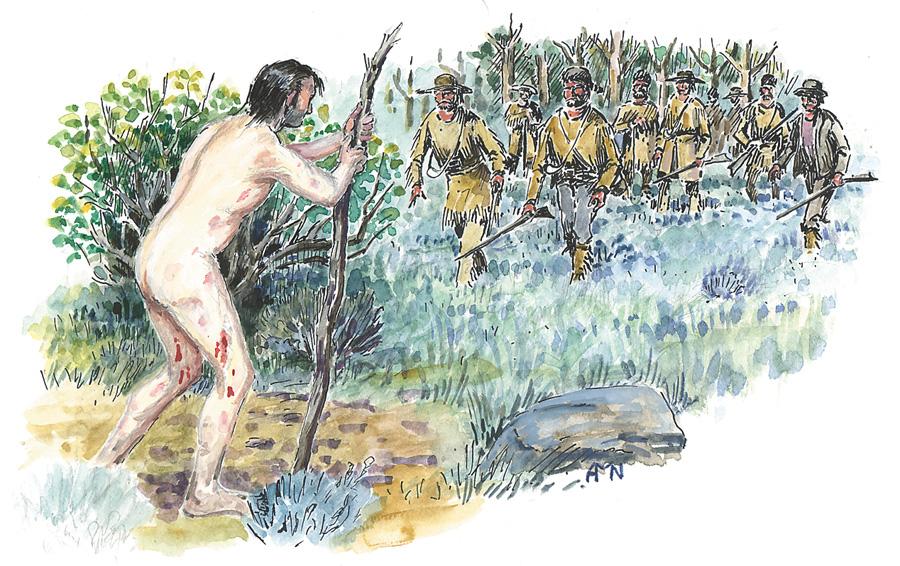

Sure enough, when the sun winked over the eastern horizon, it was a signal. A few guns stuck out over the palisades and one shot was fired at the white men. Arrows sizzled and then there was a roar of gunfire. About 600 Arikara Indians intended to wipe out the white men. Jed Smith and his men stepped behind the horses for cover but it didn’t take long for the animals to be mowed down. The white men then hunkered down behind the carcasses.

The keelboats were about 90 feet away from the shore. Ashley was up and ordered his French engagés to take the boats closer in to rescue Smith and the others. The Frenchmen shook their heads like stubborn mules. Getting killed was not their idea of a good way to start the day. Ashley later wrote, “. . . notwithstanding every exertion on my part to enforce the execution, I could not effect it.”

James Clyman wrote there were “many calls for the boats to come ashore to take us on board but no prayers or threats had the slightest effect the Boats men being completely paralyzed.”

Tim Simmons, in addition to writing for Wild West, Persimmon Hill and numerous other publications, has also written two books, Up From the Ashes and Brothers of the Pine.

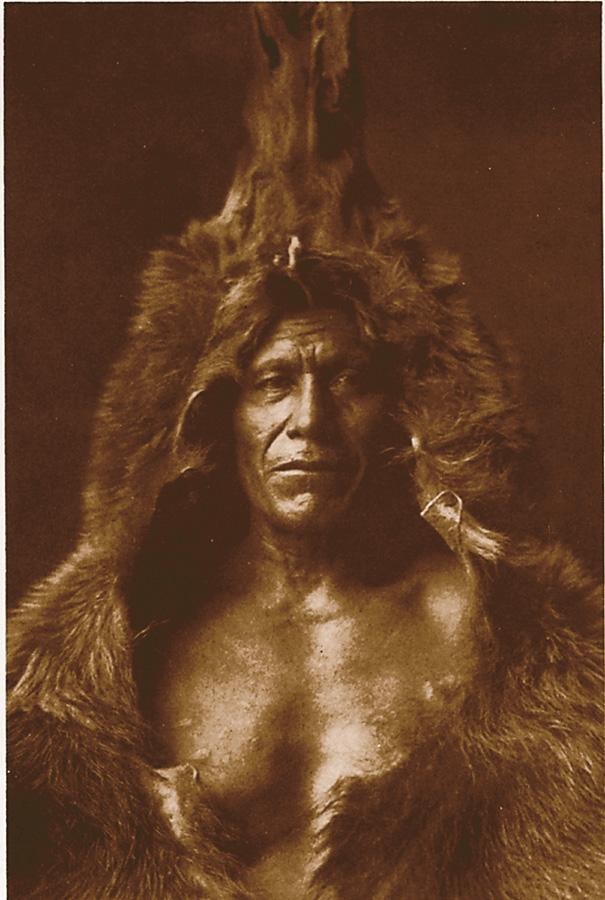

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– Illustrations by Al Napoletano –

– Illustrations by Al Napoletano –