Few folks driving on the old Ghost Town Trail northeast of Tombstone, through Gleeson, Courtland and Pearce are aware of the fact that it was quite a boom town after the decline of the silver rich city on Goose Flats.

The town was named for Jimmy Pearce. He and his family arrived in Tombstone in the 1880’s. Jimmy worked in the mines while his wife ran a boarding house. When the bottom dropped out of the silver market in 1893, Jimmy and his two sons, John and Billy started a little cow ranch in the Sulphur Springs Valley, east of Tombstone.

A prospectors dream came true for the Cornishman one morning in 1894 while moving some cattle. He stopped to rest on the side of Six Mile Hill and like any hard-rock miner he couldn’t resist examining the local geology. Despite the fact that for some twenty years prospectors had been scouring those hills, Jimmy idly picked up a piece of quartz and smashed it against a ledge. He broke it open, exposing an interior that was pure gold.

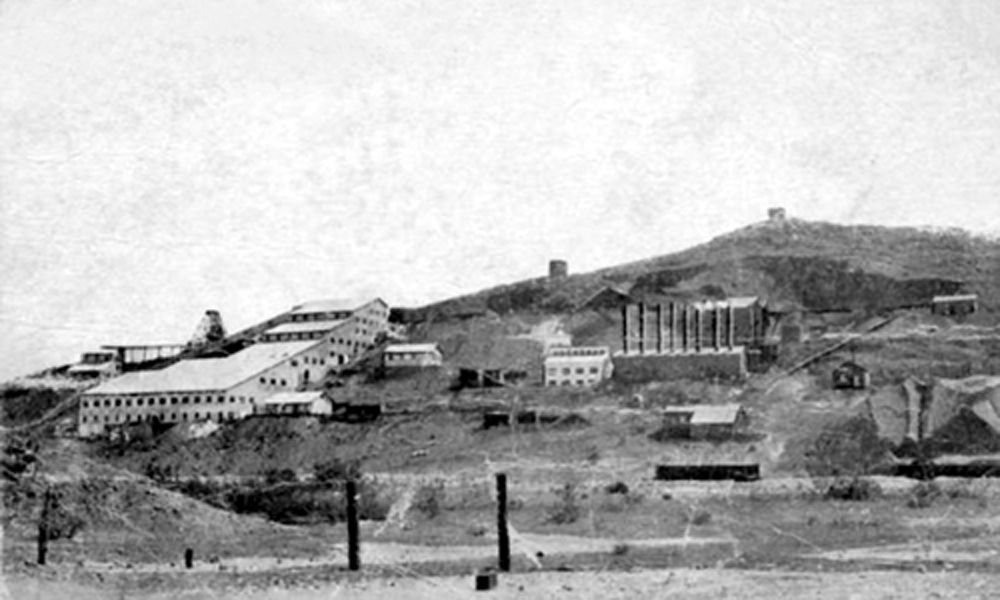

He staked claims for everyone in his family and named the claims the “Commonwealth,” then hauled a carload of ore to El Paso that assayed out at $80 to the ton in silver and $20 in gold. Almost overnight the town of Pearce materialized on the foot of the slope.

In spite of the bad silver market and two depressions the Commonwealth remained one of Arizona most profitable mines. At the time silver was thirty to fifty cents an ounce and gold, twenty dollars an ounce. Had the price of silver been as high as it was during Tombstone’s heyday it would have rivaled the production of the “Town Too Tough to Die.”

There have been exaggerated stories about the total wealth of the Commonwealth. One claimed over the first eight years it produced some $30 million in gold.

A banker from Silver City, New Mexico named John Brocknow talked Jimmy into selling out for a quarter of a million dollars. This wasn’t uncommon; most prospectors lacked the capital to develop their findings and often sold out for a few dollars but Pearce held out for more. In addition, since many considered the hotel business a more reliable profit maker than mining, Mrs. Pearce demanded and received the lucrative exclusive on the hostelry business in the town.

It wasn’t long before people begun drifting in, looking for employment and other get-rich-quick opportunities. Some residents of Tombstone even dismantled their homes and businesses and packed them over to the east side of the Dragoon Mountains and reconstructed them in the new town.

Among them were Joe and Maulda Bignon, the owners of the famous Bird Cage Theater. Maulda, better-known as Big Minnie was one of Tombstone’s more colorful “boom-town belles.”

Minnie stood over six-feet-tall and weighted 230 lbs. She was pure loveliness in pink tights. She’s buried in the Pearce cemetery as is Arizona Ranger Billy Olds, whose wife shot him for philandering.

The sequel to the Pearce family is a mystery. There seems to be no record of what became of them, the quarter of a million dollars, or the boarding house monopoly. Perhaps they returned to Wales and moved into a castle.

Over the next few years different several corporations held ownership in the Commonwealth.

The boom times in Pearce peaked in 1919 with a population of fifteen hundred. The town had the usual assortment of stores, saloons, bordellos, restaurants and even a movie theater.

The Great Depression took its toll and the railroad that was built from Douglas in 1903 pulled up its tracks in the 1930s causing Pearce to steadily decline. The final blow came when the seemingly inexhaustible Commonwealth Mine finally played out. By that time the price of silver hit rock bottom. It’s estimated the mine about ten million dollars, eighty percent of that silver and the rest gold.

A story is told that in the mines early day’s some thieves stole large amounts of mercury-laden amalgam which was used for retorting or separating the gold and silver from the ore. Since they had no apparatus to retort the minerals they cooked off the mercury over an open stove. They had no idea the fumes were highly poisonous and could be fatal. One of the side effects was loss of hair and teeth. A doctor had to be called in to save their poor hapless lives. In the end the company recovered their gold and silver. The owners decided the toothless, hairless thieves had suffered enough and didn’t press charges.

Like this story? Try: “To Honor Men Who Dig For Gold”