AUNT SALLY—FIRST WOMAN IN THE BLACK HILLS. That’s all it says on her simple, rough wood headboard that now hangs in the Adams Museum in Deadwood. A new marker was erected in 1934 at her grave in the old Vinegar Hill Cemetery, high on the wooded hill above the once bustling mining town of Galena. It says:

AUNT SALLY—FIRST WOMAN IN THE BLACK HILLS. That’s all it says on her simple, rough wood headboard that now hangs in the Adams Museum in Deadwood. A new marker was erected in 1934 at her grave in the old Vinegar Hill Cemetery, high on the wooded hill above the once bustling mining town of Galena. It says:

“Aunt Sally, Sarah Campbell, colored, died 1887. As a Member of the Custer Expedition to the Black Hills in 1874 She Ventured with the Vanguard of Civilization. 1874. – Erected by Her Friend and Neighbor – 1934.”

Sarah Campbell truly found herself in the vanguard of civilization as she entered the Black Hills with the Custer Expedition in 1874. No non-Indian woman predated her entry. Cook and prospector on the expedition, and pioneer of the Black Hills, “Aunt Sally” holds a memorable place in the frontier history of Dakota, in Western women’s history, and in African-American history. Her rightful place is inadequately chronicled, eclipsed by another woman—Annie Tallent, a white woman—whose illicit venture into the Black Hills (illegally prospecting for gold) followed Aunt Sally by six months.

Though Tallent came to be celebrated as the region’s most distinguished pioneer woman for over a century, recent acknowledgment of Tallent’s flawed character has marred her position. The cloak of honor now falls, rightfully, to Sarah Campbell.

It was the summer of 1874, and Sarah Campbell, affectionately called” Aunt Sally” by the troopers of the Seventh Cavalry, was a member of Lt. Colonel George A. Custer’s expedition to the Black Hills of Dakota. The former slave, Kentucky-born, was a camp cook on that expedition of over a thousand men.

Riding in a covered wagon, loaded with rattling pots and pans, Aunt Sally was indeed on an epic adventure that was pivotal to opening the Black Hills to frontier expansion.

Sources differ regarding precisely for whom Aunt Sally cooked on this expedition. Some say she cooked for Captain Myles Keogh, some say for Colonel Custer himself; others say she worked for the regiment’s sutler John Smith. Charles Windolph, the last living white survivor of the Little Big Horn (with Reno’s command), and Dan Newell, a trooper with Custer in 1874, insisted that Aunt Sally cooked for Captain Keogh. Keogh, they said, was a Southern gentleman of means, and obtained “Aunt Sally” in the South. Aunt Sally “would use her frying pan on any trooper who got fresh with her,” and was highly respected. If a man claimed he served with Custer in ’74, Newell and Windolph would challenge him, “Who was the woman in the expedition?” If the answer was not Aunt Sally, well, he was a liar. “Everybody in that expedition knew Aunt Sally.”

But the two old soldiers were confused when they were interviewed 50 years later. Aunt Sally did not cook for Keogh in the Black Hills—he was not even present. Keogh left Fort Totten April 6 on a seven-month furlough, and spent most of 1874 in his native Ireland (no, he was not a Southerner), returning in November.

Nor was Aunt Sally Custer’s cook. “Johnson, our new colored cook, had hot biscuit [sic], and this morning hot cakes and biscuit,” wrote Custer to his wife Libbie July 3, the day after departing Fort Lincoln. July 15 Custer wrote, “Our mess is a gratifying success; Johnson is not only an excellent cook, but is also very prompt.”

It was Custer’s custom to use female cooks, often bringing them on campaigns—Eliza Denison Brown during the Civil War; Susan Elizabeth “Eliza” Tinsley Mundy at Fort Leavenworth; and sisters Mary and Marie Adams at Fort Lincoln (Custer brought Mary on the 1873 Yellowstone campaign). Historian John Manion identifies “Johnson” as Nancy Mucks Johnson (later Millett), a cousin of

the Adams women. A 1922 document describes Nancy Millett as a colored cook then living in Bismarck, “a relative of Mary Adams . . . who came to Fort Lincoln to work for Lieutenant Calhoun.”

“Johnson” could very well be Nancy Johnson, the second woman on Custer’s expedition. This indeed contradicts traditional Black Hills history which maintains that Aunt Sally was the sole woman on the expedition. This does not diminish, however, Aunt Sally’s position as the first non-Indian woman who entered the Black Hills, and settled there as a pioneer.

Aunt Sally neither cooked for Custer nor Keogh—she cooked for sutler John Smith, in accord with the Black Hills Daily Times of 1880. She is often quoted as calling herself “the only white woman that ever saw the Black Hills.” Seth Galvin, who knew Aunt Sally when he was a boy, said she called herself a white woman because “She was not very literate, and the term ‘white’ was the only [term] she knew. She meant ‘civilized.’”

Confusion still prevails, nonetheless, in government records. It is, however, understandable that Sally is not in the military records because civilian employees were not hired by the government, and consequently would not appear on the quartermaster’s “Reports of Persons and Articles Hired.” But contrary to military records, Mary Adams did not accompany Custer to the Black Hills; she remained at Fort Lincoln as Libbie’s servant. When Custer’s returning column appeared, a Custer house-orderly “went to Mary to tell her the news” they had returned.

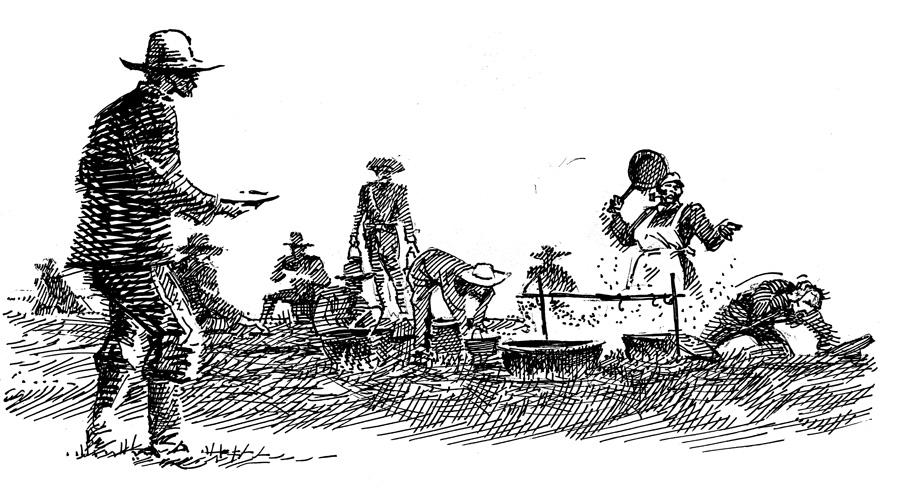

The essential fact remains: Aunt Sally was there, whomever she served, rising at first reveille at 2:35 a.m. to unload the mess gear, build her fire and prepare breakfast.

Life in the Seventh Cavalry must have been unlike any experience Sally had ever encountered. The Black Hills abounded in wooded heights with pure mountain water tasting like ambrosia, a luxurious contrast to the hot and arid alkaline plains below in the vastness of Dakota. Flower-filled meadows flourished. Music filled the air with rousing renditions of “Garry Owen” and sentimental ballads like “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” Concerts were given every evening by a 16-piece military band, who rode matched white horses, a Custer innovation. When the command entered a park-like area that Custer dubbed Floral Valley, happy soldiers decorated their horses with wildflowers, and the band scrambled up on a ledge to serenade them with old favorites—“notes echoing from peak to peak.”

As Custer’s command wound through the pristine reaches of the Hills, the Seventh in the lead, Aunt Sally was there riding the crest of its golden moments. Finally, they made “permanent camp” at French Creek, east of present-day Custer, near Harney Peak, the highest mountain between the Rockies and the Atlantic.

When the command moved out from Fort Lincoln, wagons four-abreast, it was ostensibly to search for a suitable site for a military post “to keep the Indians under control—just in case.” In actuality, the government wanted to authenticate the persistent rumors of gold in the Black Hills.

The expedition’s miners Horatio Ross and William McKay had gold-panned since entering the Black Hills, finding specks here and there. Now at French Creek on July 30, Ross made his historic discovery: indeed there was GOLD in the Black Hills!

Everyone tried prospecting, including Aunt Sally who staked out her claim, “No. 7 below Discovery.” The first mining company in the Black Hills formed around a campfire, amidst a cluster of wagons on French Creek. August 5, five days after the discovery that would dramatically impact the course of Western expansion. Observing the law, they authorized officers and a board of directors, and posted a notice on the claim, inside the cover of a hardtack box:

District No. 1 Custer Park Mining Company, Custer’s Gulch, Black Hills, D.T., August 5, 1874—Notice is hereby given that we the undersigned claimants do claim 4,000 feet commencing at No. 8 above, and running down to No. 12 below Discovery, for mining purposes, and intend to work the same as soon as peaceable possession can be had of this portion of Dakota Territory by the general government.

Listed on the historic document, claiming No. 7 below Discovery is the name Sarah Campbell. The Custer County Records still contain Aunt Sally’s claim to No. 7.

Jimmy Calhoun’s diary states, “Ross was given the first 400 feet designated as ‘Discovery.’ Claim No. 7 below Discovery belonged to ‘Aunt Sally,’ sutler John W. Smith’s Negro cook. Sally’s real name was Sarah Campbell, a woman Curtis [the correspondent] described as ‘a huge mountain of dusky flesh.’”

It seems Aunt Sally was up to her elbows in a gold strike! Aunt Sally traveled back to Fort Lincoln with the expedition, August 30, resolving to return to the Black Hills. William Curtis, 23-year-old star reporter for the Chicago Inter-Ocean and the New York World, published his interview with Sally in the Inter-Ocean, August 27, 1874:

The most excited contestant in this chase after fortune was “Aunt Sally,” the sutler’s colored cook . . . She is an old frontiersman, as it were, having been up and down the Missouri ever since its muddy water was broken by a paddle wheel, and having accumulated quite a little property, had settled down in Bismarck to ease and luxury.

“Money didn’t done brung dis chile out hyar, now, I tells ye dat; dis hain’t no common nigger, . . . and ye wouldn’t cotch dis gal totin’ chuck out hyar now, I tells ye, if it hadn’t bin for seein’ dese hyar Black Hills dat Custer fetched us to. I’se heered ‘bout dese here hills long ‘fore Custer did. . . . I was on de Missouri — cooked on first boat dat ever run up dat stream. But I wanted to see dese Black Hills — an’ dey ain’t no blacker dan I am and I’m no African, now you just bet I ain’t; I’m one of your common herd.

She “scratched grabble” and staked out her claim, wrote Curtis, and says she’s “coming here as soon as anybody.”

Aunt Sally vowed to return, and return she did. Sally literally walked back to the Hills beside an ox-drawn wagon. She filed a claim at Elk Creek, and lived on a small ranch there. She prospected, cooked, and midwifed at Crook City and Galena where she lived her final years, its most famous resident. Once a bustling silver-mining town in a gulch beside Bear Butte Creek, Galena had many civilized amenities: a sawmill, smelter, narrow-gauge passenger train, four stores, three butcher shops, drinking establishments, and an opera house. Yet, it was still a virgin land with fierce predators, and mountain lions occasionally came prowling into town.

A well-beloved figure in the Hills, Aunt Sally frequently rode in civic parades at annual celebrations. “Pipe-smoking” Aunt Sally particularly enjoyed telling colorful anecdotes about the Custer Expedition, “puffing on her pipe, her ample sides shaking with merriment. The main character in all her tales was her hero.

Ramona Rand-Caplan is a freelance writer who lives in Trinidad, Colorado. This is her first article for True West.

Photo Gallery

– South Dakota State University –