The New York Herald dubbed The North American Indian (TNAI) as the “most gigantic undertaking in the making of books since the King James edition of the Bible.” Curtis, the West’s greatest Indian photographer, had a profound effect on how Whites viewed the many Native American cultures. He also instilled a sense of pride for Indians in their heritage. The final volume of TNAI was published in 1930. In the end, it required 30 years and over 40,000 photographs of 80 tribes along with 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of Indigenous languages and music to complete his mission. Each of the 20 volume sets contained 2,234 original photogravures (the 20 books contained a total of 1,511 photogravures and the 20 large portfolios a total of 723 photogravures), 2.5 million words of enlightening anthropologic text, and numerous transcriptions of language and music. It would cost over $30 million in today’s money. Much of the funding would come from the House of Morgan.

There is a moment in time when your dreams and history form a perfect world. For Curtis 1907 would be that moment. An argument could be made that 1907 was the pinnacle of Curtis’s life. Fresh funds from banker J.P. Morgan had not yet been spent, and the High Plains and all it promised unfolded under the big sky. Momentum for honoring the Indigenous people of North America was increasing. For example, in 1907 they were celebrated on a ten-dollar gold piece (Eagle) designed by America’s finest sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The obverse featured an Indian adorned in a full war bonnet. A generation earlier that tribute would have been unthinkable. That same year Charles Lummis founded the Southwest Museum of the American Indian in Los Angeles.

In Pursuit of Custer

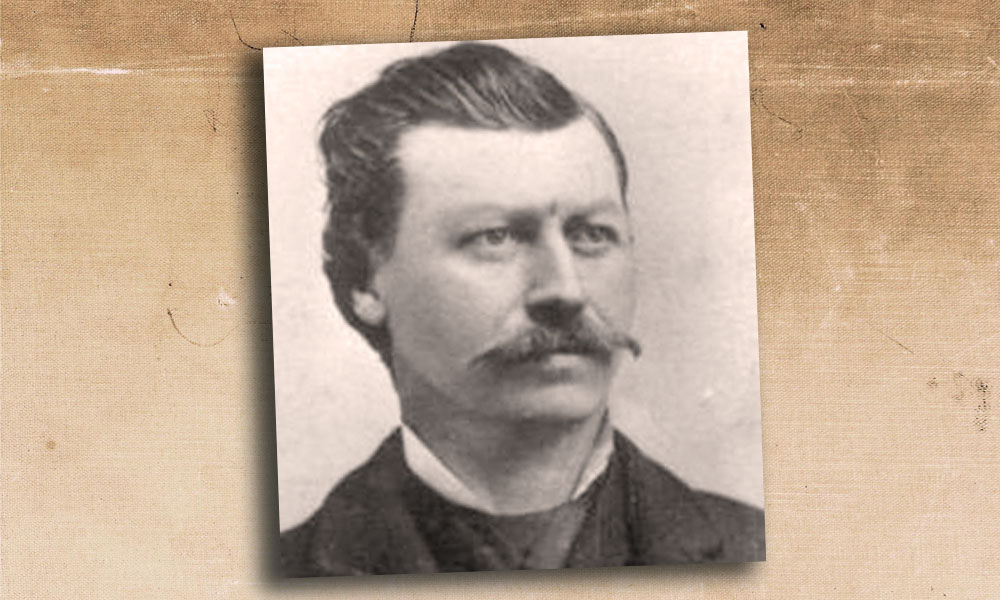

The Shadow Catcher was looking ahead to his future volumes, ones on the Sioux/Cheyenne and Crow (Apsaroke) in Montana and the Dakotas. Yet, as countless others before him, he became obsessed with the Custer stories, declaring, “They got into my brain and I cannot shake it off.” His first visit to the Custer Battlefield as it was known at the time was in 1905. Curtis struck gold when he hired local legend, full-blooded Crow Alexander Upshaw, son of Crazy Pend d’Orielle and his wife, Good Hair. He was born in St. Xavier, Montana, in 1874. Curtis and Upshaw probably first met in 1905 when Upshaw was Curtis’s translator and organizer on his trips to Indian reservations in Montana. Having grown up on the Crow Reservation, Upshaw appeared to have his finger on the pulse of everything in southeastern Montana. Curtis immortalized him in a portrait with full headdress in Volume IV. Upshaw was a product of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, and one of William Pratt’s success stories. He thrived at the school, heading up the debate team and writing articles in such publications as Red Man and Helper, where he urged Indians to travel and learn the white man’s world. After graduating in 1897, he remained an advocate for the values taught at the boarding school.

Upshaw became an outstanding spokesman for the Crow people. For example, in 1909 he joined Curtis on his trip to Washington, D.C., where he met President Theodore Roosevelt and discussed the difficult conditions on the Crow Reservation. Curtis assistant William Phillips wrote that the local Whites called Upshaw “lazy, dishonest, meddlesome, here today and there tomorrow, a regular coyote,” the standard description Whites gave most Indians. Undaunted, Curtis placed Upshaw on the payroll in part to crack the Custer story. Dozens had been given their shot at it, but beaming with hubris, Curtis believed he would be the one to tell the true Western saga. Leaving his reputation in the hands of heavy-drinking Upshaw would prove unwise.

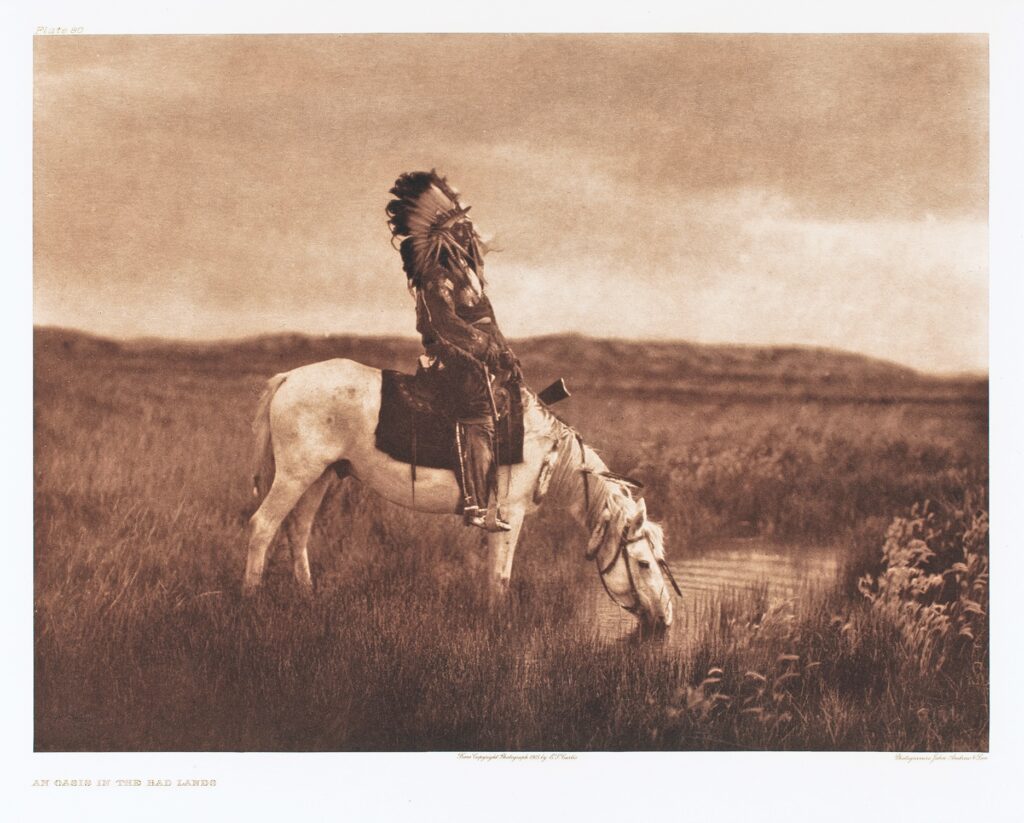

Curtis photogravure, Vol. IV, 1909

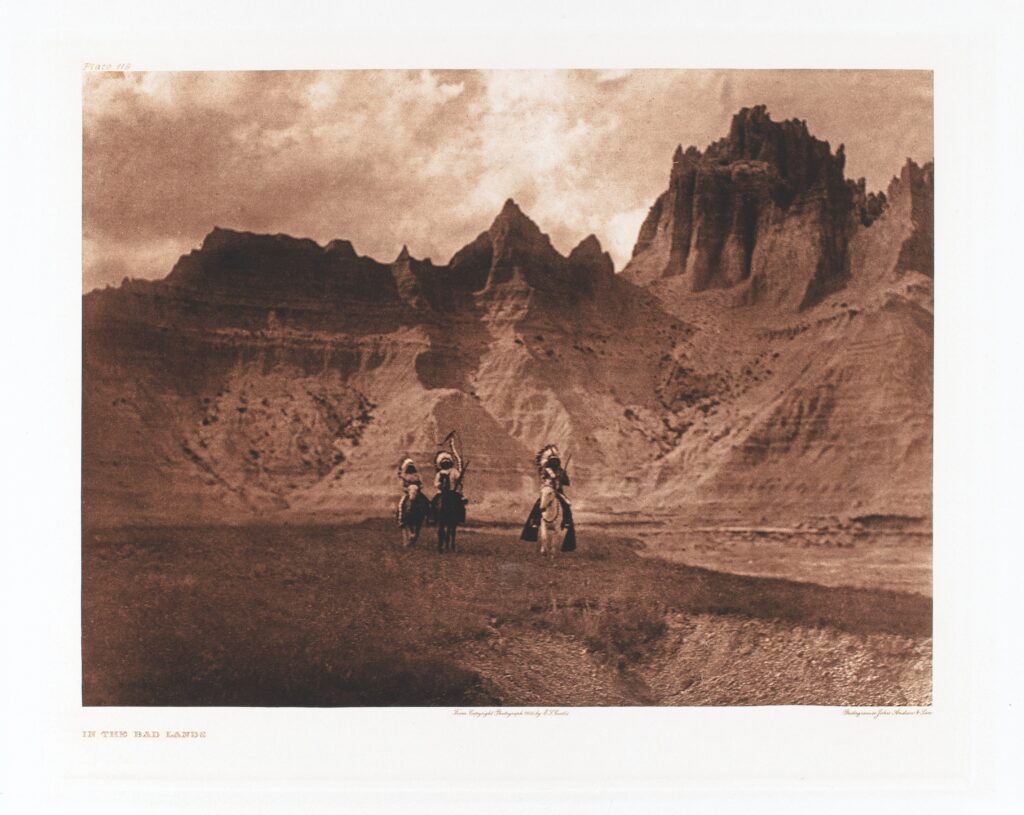

Curtis photogravure, Vol. VI, 1911

Curtis had been obsessed over the past three years to find out what really happened on the battlefield. Custer was still a national hero at the time. Yet, it was more than a battle, it was a defining moment in American history. His goal was to “form a comprehensive and permanent record” in his TNAI text. He was standing at ground zero for the most famous happening in the 19th-century West. No other battle in American history except Gettysburg has had more written about it. In the 19th century, Custer was a genuine national superstar. Curtis’s revelations back East would certainly fetch new subscriptions, so he thought.

Ever since the battle ended in 1876, artists, photographers and writers have added to the myth of Custer’s Last Stand. So too have some of Custer’s Crow scouts—Curley, Goes Ahead, Half Yellow Face, Hairy Moccasin, White Man Runs Him and White Swan—who attempted to warn Custer about the size of the encampment but to no avail. As the years passed, they would all vie for attention as they presented themselves as eye-witness experts on the battle. For a price, they delivered whatever their interviewers wanted to hear. For example, Goes Ahead told his wife Pretty Shield that Custer was shot and fell into the river. He, Hairy Moccasin and White Man Runs Him then fled the battle scene. In reality, Custer didn’t fall into the river, and they had left well before the battle. Pretty Shield later became famous when Frank Bird Linderman wrote her biography, Red Mother, which was published in 1932. In 1931 Linderman had published the classic American: The Life Story of a Great Indian (Plenty Coups). Plenty Coups was the chief of the Crow and one of Curtis’s favorite subjects.

The Scouts

Upshaw secured the services of three of Custer’s Crow scouts—Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin and White Man Runs Him. After leaving Custer, some had found refuge with Reno’s soldiers who had retreated to a safe position on the ridge. The scouts had been paid to find the village, not to fight the Sioux. With shocking information, the three informed Curtis that Custer had passively watched from a high point on the ridge as Reno’s troops were pummeled. To give credence to the idea that he held no grudge against Custer and make his fabrication more believable, White Man Runs Him insisted that Custer “was always very good to us Crow scouts, and we loved him.” This revelation of betrayal of Reno was just the sensational story Curtis needed to sell sets of TNAI and enhance his standing as a brilliant researcher. Curtis became convinced that the three Crow scouts were telling the truth. Upshaw most likely thought his reputation would also be elevated nationally by this revelation.

This tale could never hold muster. When attacking Indian villages, Custer went with a multipronged attack, charging from several directions, just like he had done in the Civil War and Washita. Robert M. Utley in The Lance and the Shield (1993) brought clarity to the controversy. He wrote, “From the blufftops he saw the village for the first time and watched Major Reno open the battle at the upper end. Then Custer led his men down a ravine that opened on upper Medicine Tail Coulee.” Benteen never showed up, but large numbers of Indian warriors did. In the most detailed account, battle expert Evan S. Connell in Son of the Morning Star: Custer and the Little Bighorn (1984) wrote, “The last time any of the survivors saw him alive, with two or three questionable exceptions, was shortly after he turned up into the eastern hills. Reno’s men in the valley saw him wave his hat, presumably to encourage them. Then he spurred his horse and rode out of sight.” In reality, Custer never lingered.

The three scouts had been seeking publicity ever since the battle because they felt they had never received the notoriety they deserved. Another scout, Curly (Ashishishe), for decades had gained a national reputation as the sole survivor of the Custer massacre, a status the others envied. Curly initially reported that he watched the battle between the Sioux/Cheyenne and Custer’s troops from a distance. Curly, at 19 years old, claimed he stuck with Custer long after the other three scouts had fled. Soon after the battle famed photographer D.F. Barry snapped famous portraits of Curly, adding to his celebrity. In total, over 100 photographs were taken of him by a number of photographers. Later, Curly changed his story and said that he was with Custer at the Last Stand and disguised himself as a Lakota warrior to escape. His family’s story was that after Custer fell, he hid inside a gutted horse to avoid detection. In the June 1906 Scribner’s Curtis wrote, “Among the dozens of Indians I questioned of the fight was Curley [sic] who is so often called the sole survivor of the Custer fight. He has been so bullied, badgered, questioned, cross-questioned, leading-questioned, and called, by mouth and in type, a coward and a liar by an endless horde of the curious and the knowledge-seeking, that I doubt today, if his life depended upon it, he could tell whether he was ever at or near the Custer fight.”

Loving the melodramatic, Curtis remained convinced that Custer was a coward and Reno a victim. He wrote in his notes, totaling 100 pages just on the battle, “Custer watched all of this for 45 to 60 minutes, and the whole fight was so close to him that he could have been in the thick of it in five minutes.” In the fall of 1907 Curtis’s team, including Upshaw and lead assistant William E. Myers, stayed at a cabin on the Crow reservations to finish the writing for Volume III and work on a separate book on the Crow and Hidatsa.

A fold-out map of the battle scene was included on page 44 of Volume III. The revelation that Custer had watched Reno’s retreat without intervening was first revealed to his friend, professor Edmond S. Meany back in Seattle. Curtis wrote, “Has there been anything published on the fact that Custer, from the highest viewpoint of the region, watched Reno’s charge, battle, and defeat?…. It puts an entirely new light on the entire Custer fight.” Meany wrote back that he was playing with fire. Curtis defensively wrote, “This is not a pipe dream on my part. I have ridden the battlefield from end to end, back and forth from every important point on it, noting carefully the time of such rides.” Perhaps, this was another exaggeration.

The Crash

Then, events far away rocked Curtis’s world. The Panic of 1907 began over a three-week period in October. Stocks fell 50 percent, and there was a run on the banks as the world’s financial system teetered on collapse. After a few months, the economy and markets slowly recovered. Curtis wrote to Charles Lummis, “Confidentially, the fact that the stock market has gone to the bow-wows is making my work a bit difficult.” In early 1908 Curtis returned to New York City to give Morgan’s librarian Belle da Costa Greene an update for the titan and to solicit new subscriptions but with little success. The big event was Curtis publicly dropping the bombshell about Custer being a coward. Criticism was sudden and vicious and came from many corners, including Libbie Custer and her supporters. Even though her husband left her in debt, Libbie spent the rest of her life creating his legend in her books and defending his honor.

Wounded by the furor, Curtis sought support from President Theodore Roosevelt. On April 8, 1908, the president gave his terse response:

“My Dear Mr. Curtis: I have read those papers through with great interest, and after reading them, I am uncertain as to what is the best course to advise. I never heard of the three Crow scouts that you mention, and did not know that they were with Custer. I need not say to you that writing over thirty years after an event it is necessary to be exceedingly cautious about relying upon the memory of any man, Indian or white. Such a space of time is a great breeder of myths. Apparently you are inclined to the theory that Custer looked on but a short distance away at the butchery of Reno’s men, and let it take place, hoping to gain great glory for himself afterward. Such a theory is wildly improbable. Of course, human nature is so queer that it is hard to say that anything is impossible, but this theory makes Custer out to be a traitor and a fool. He would have gained just as much glory galloping down to snatch victory from defeat after Reno was thoroughly routed.”

Poof. Three years of work on the story went up in smoke. Discouraged, Curtis wrote an army colonel, “I am beginning to believe that nothing is quite so uncertain as facts.” Any mention of his theory never ended up in Volume III. Curtis recanted and wrote Meany, “Don’t have a cold chill when I say I brought in my material. I have been very guarded and while giving a great deal of new and interesting information, I have said nothing that can be considered a criticism of Custer.” He especially didn’t want to upset Chief of the U.S. Forest Service Gifford Pinchot who had just named a national forest after Custer. A sense of risky adventure always entered into Curtis’s efforts, part of his melodramatic personality.

Working on Volume IV, Upshaw was Curtis’s tireless front man as they investigated the Apsaroke (Crow) in southern Montana. The summer of 1908 saw Upshaw across the border in western North Dakota building friendships with the Mandan in anticipation of release of Volume V about them in 1909. The next volume was released two years later. Reviews of the first volumes were laudatory. The Review of Reviews wrote, “The North American Indian cannot be compared with any publishing venture in the annals of American bookmaking, or indeed in those of any other nation.” His friend Clinton Hart Merriam, now head of the Bureau of Biological Survey, wrote, “Every American who sees the work will be proud that so handsome a piece of book-making has been produced in America; and every intelligent man will rejoice that ethnology and history have been enriched by such faithful and artistic records of the aboriginal inhabitants of our country.”

Accolades were indeed in order. The first five volumes of TNAI showcased some of Curtis’s finest photogravures and text: Volume I (1907): The Vanishing Race—Navaho, Geronimo—Apache, The Chief of the Desert—Navaho, and Cañon de Chelley—Navaho. While the famous The Vanishing Race—Navaho (1904) was picked as the first portfolio image, lesser known is its optimistic opposite, Out of the Darkness (1904). Curtis noted where it was shot, “In Tesakod Cañon, a branch of Cañon de Chelley. At the point where this picture was made the gorge is very narrow;” Volume II (1908): Mosa—Mohave, Qahatika Girl; Volume III (1908): In The Bad Lands, Prayer To The Mystery, and An Oasis In The Bad Lands; Volume IV (1909): The Oath, The Spirit Of The Past—Apsaroke, and Crying To The Spirits; and Volume V (1909): Bear’s Belly—Arikara, Offering The Buffalo Skull—Mandan, and in The Medicine Lodge—Arikara. Of the haunting The Spirit of the Past—Apsaroke (1908), Curtis wrote, “A particularly striking group of old-time warriors, conveying so much of the feeling of the early days of the chase and the war-path that the picture seems to reflect in an unusual degree ‘the spirit of the past.’” The first two volumes were originally planned to be published at the same time in late 1907, but work on Volume II delayed its release until 1908.

To honor Curtis’s achievement, Roosevelt invited him to the White House in February 1909. Upshaw accompanied him. A reception was held for Curtis that was attended by the president and Vice President Taft. Even though Curtis was able to convince Andrew Carnegie to finally sign up for a subscription, sales continued to be anemic. There was additional bad news later that year. Upshaw was found dead in a jail cell in Billings. He was 38 years old. Apparently, he had been drinking and was transported to jail to dry out. He died after an episode of vomiting blood in his jail cell. Some of his Crow friends told Curtis that he had gotten into a fight with several White men who severely beat him. Devastated, Curtis had high praise for his friend in Volume IV. He said he was the most remarkable man he had ever met.

The dean of Western historians, Robert M. Utley, who studied the battle as much as anyone wrote, “Then on June 25, 1876, history merged with legend to award George Armstrong Custer immortality. The Battle of the Little Bighorn cut short a career that would have gained occasional mention in the histories of the Civil War and the western frontier. Instead, it made the slain Custer’s name a household word then and forever after—an icon in the public imagination, at times bright, at times tarnished, but never in danger of decay.” The reflective Utley wrote, “The simplest answer, usually overlooked, is that the army lost largely because the Indians won. To ascribe defeat entirely to military failing is to devalue Indian strength and leadership.” And Custer almost cut short Curtis’s career.

“Custer Almost Kills Curtis” is excerpted from Western American art historian Dr. Larry Len Peterson’s latest book, Edward S. Curtis: Printing the Legends, Looking at Shadows in a West Lit Only by Fire. The award-winning author lives with his wife LeAnne on their Spirit of Winter Ranch near Sisters, Oregon, in the shadows of the Three Sisters Mountains—Hope, Faith and Charity.