After a gunfight or Indian attack, what happened to the weapons of the fallen?

Edward Presken – Mobile, Alabama

To the victor go the spoils. If Indians won a battle, and if time permitted, they could gather in the loot, clothes, firearms and ammunition to stock their needs. When the Army collected non-military firearms after a battle, such as repeating rifles, ammo, etc., the arms were sent back to the Rock Island Arsenal, Illinois. From there they would likely be sold as surplus. And the winner of a gunfight could claim the weapons of his

opponent, if he chose to.

What happened when Doc Holliday was in Prescott, Arizona?

Bill Jenkins – Shreveport, Louisiana

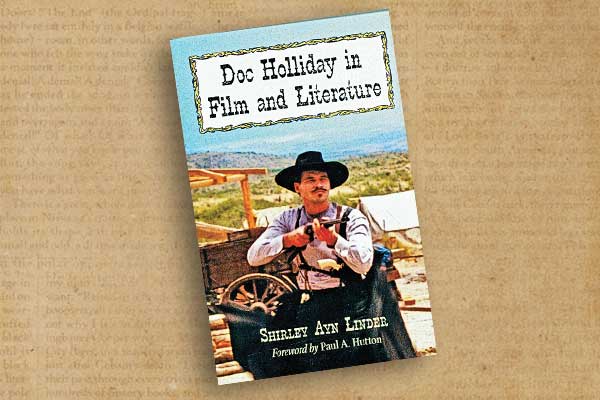

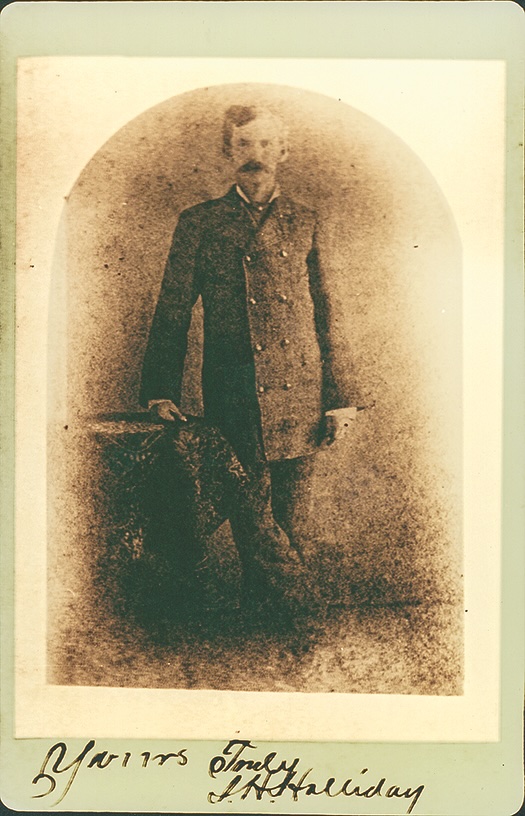

Prescott Historian Brad Courtney informed me “Doc and Kate left Las Vegas, New Mexico, in October 1879 bound for Prescott with Wyatt and James Earp and their families. The Earps headed for Tombstone in December, but Doc and Kate remained through the winter. Wyatt kept urging him to join them in Tombstone, but rather he headed back to Las Vegas that spring to pay off some debts while Kate went to Globe. According to the 1880 census, Doc was back in Prescott before June and remained until August before heading to Tombstone.”

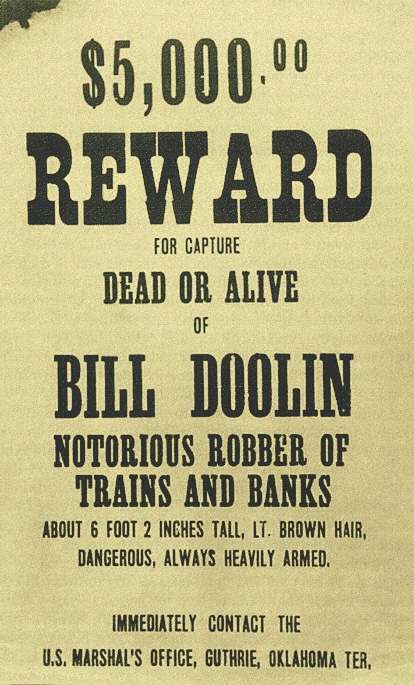

Were lawmen able to collect reward money?

Roger Tinklenberg – Westminster, Colorado

True West Archives

Yes. Most lawmen—federal and local—could collect rewards in addition to regular pay. For some, that money was necessary to get by. And he could also put in for expenses, like travel, food for the animals, housing, etc.

When Indians attacked wagon trains, did they really ride around the wagons in a circle like they show in the movies?

Ed Dickens – Joplin, Missouri

Attacks on large wagon trains were rare if ever, especially if an experienced wagon boss was in charge. He demanded discipline and always had a defense plan in case of an attack. Indians might attack a small train of two or three wagons, but it was usually an ambush. Occasionally they would pay a social visit to the wagon train just to probe for weakness or lack of discipline. If they found it was well-defended, they’d go looking for another prey. And their tactics depended on the situation they faced.

Who was John “Portuguee” Phillips?

Joe Manriquez – Whittier, California

Early in 1866, John “Portugee” Phillips joined a party that was coming to the Big Horn Mountains to prospect for gold. His group arrived at Fort Phil Kearny on September 14, and he was at the fort during the Fetterman Fight on December 21.

After Fetterman was killed, Col. Henry Carrington felt the fort might fall into the hands of the Sioux. He asked for volunteers to venture out into the blizzard and below-zero temperatures and ride to Fort Laramie to bring a relief force. Phillips and another man took the best two horses at the fort, including Carrington’s personal mount.

The faithful horse that carried Phillips the 236 miles through -20-degree temperatures, high winds, blowing snow and deep drifts, died soon after the ride was completed.

For some reason the government refused to pay Phillips and the other rider. Phillips died in 1883.

In 1900, the government paid his widow Hattie $5,000. She used some of the money to erect an elaborate monument in his honor in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Were fast-draw artists a common thing in the Old West, or are they largely an invention of pulp fiction and Hollywood?

Shawn Cote – Fort Fairfield, Maine

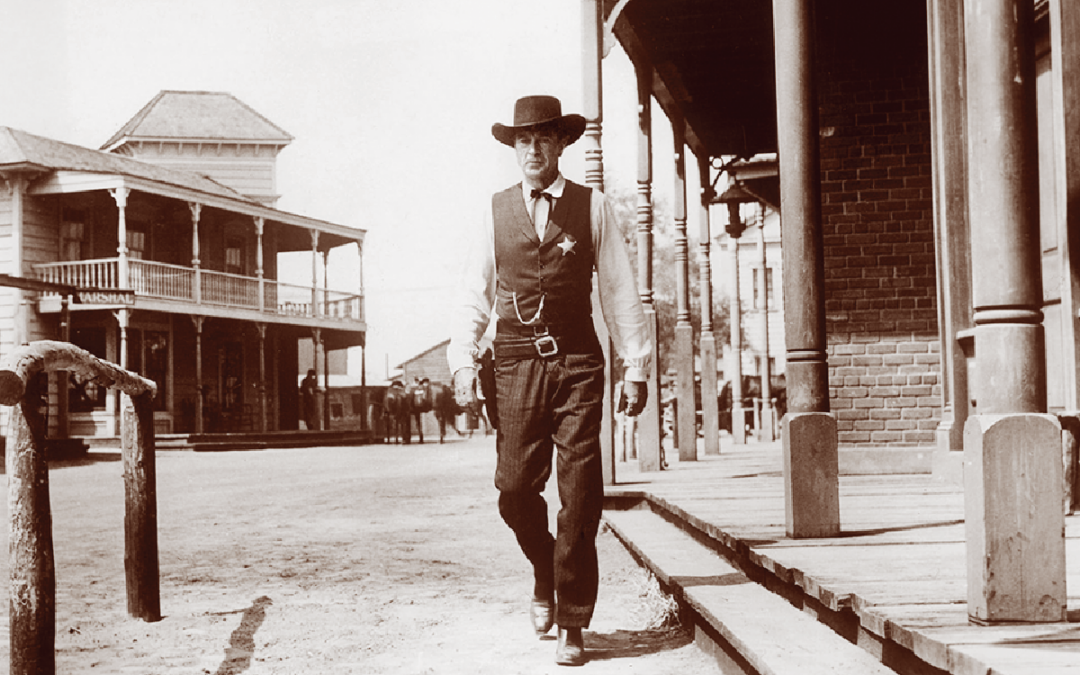

Hollywood invented the fast draw. In reality, it was a factor in only a handful of gunfights. What really mattered was accuracy. The most dangerous man in a fight was a man willing to kill, who had no hesitation to pull his pistol and fire.

Wyatt Earp allegedly put it plain and simple “Take your time…in a hurry.” Even if he didn’t say that exactly, the point still holds.