Tracking back 150 years ago, the Hayden Survey had humble beginnings, starting with the unpromising early life of its leader. Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden was born

into an unstable family and was most likely illegitimate. His father was an alcoholic, and his early years were lived in relative poverty.

He got his first lucky break when his mother sent him to live with relatives in Ohio. Here, he had a supportive aunt and uncle who provided guidance and encouraged his education. He also was introduced to the world of science when he enrolled in nearby Oberlin College in 1845.

An intensely ambitious youth, Hayden was determined to “make something of himself.” During this early period, he began to hone his skills in lobbying and self-promotion—abilities that he learned well. His first major act of self-promotion was to meet John Newberry while he was still at Oberlin. Newberry was a locally prominent scientist whose connections would be the motivating force for Hayden’s scientific career.

Newberry introduced Hayden to Dr. James Hall, who was influential in getting Hayden into medical school in Albany, New York, after he had graduated from Oberlin. With few exceptions during the mid-19th century (the Sheffield Scientific School being one), medical school was the only formal science training available.

Hayden graduated from Albany in the spring of 1853 , but he never wanted to practice medicine; he wanted to be a geologist and participate in the discovery and exploration of natural phenomena. Hall, a renowned geologist, had an abiding interest in the West and hired Hayden to conduct fieldwork that summer of 1853 as an assistant to Fielding Bradford Meek, working in the badlands of the southwestern Dakotas to study the geology and collect thousands of fossil plants and animals. That summer solidified in Hayden’s mind what he would do for the remainder of his life. He was starting on his quest to “become somebody.”

Hayden spent the next two years in individual field study in the upper Missouri River Basin, including along the upper Yellowstone River. In 1856–57, he joined Gouverneur K. Warren’s expedition to Nebraska. This work provided valuable lessons for Hayden—not the least of which was that he bristled under the command of another leader. Hayden made an unconscious vow never to be an assistant again. He wanted scientific autonomy and administrative control of his work.

In the summer of 1859, Hayden worked with Capt. William F. Raynolds in the upper Yellowstone. He spent the next few years in Washington, DC, where he wrote up and published his early work. He was starting to make a scientific name for himself.

In October 1862, Hayden enlisted in the U.S. Army and went to work as a military surgeon. He performed well, but rankled under the supervision of others—a trait that he exhibited during his entire life. He left the Army after Appomattox and was appointed, in 1865, an auxiliary professor of geology at the University of Pennsylvania. The job did not keep him in Philadelphia for long. He arranged his academic schedule to enable him to head west the next field season.

The year 1867 saw the birth of the four major surveys of Western geology and geography, funded by the U.S. government and designed to study different parts of the West and for different ends. The Hayden Survey was the largest, most prolific and well-funded of all four.

Hayden lobbied hard for and received the head geologist position for a survey of the new state of Nebraska. The government allocated $5,000 for the entire summer’s work, and his letter of appointment said he should locate and evaluate “all beds, veins, and other deposits of ores, coals, clays, marls, and peats” and “[Nebraska’s] soil, subsoils and [provide a] description of their adaptability to particular crops, and the best methods of preserving and increasing their fertility.”

This was a tall order, especially because he could not get started until June 18—a waste of nearly two months of field time. These funding delays proved a constant irritant to all of the surveys every year. Congress often did not complete appropriations until May, leaving each survey wondering when or if members could start their work for that season.

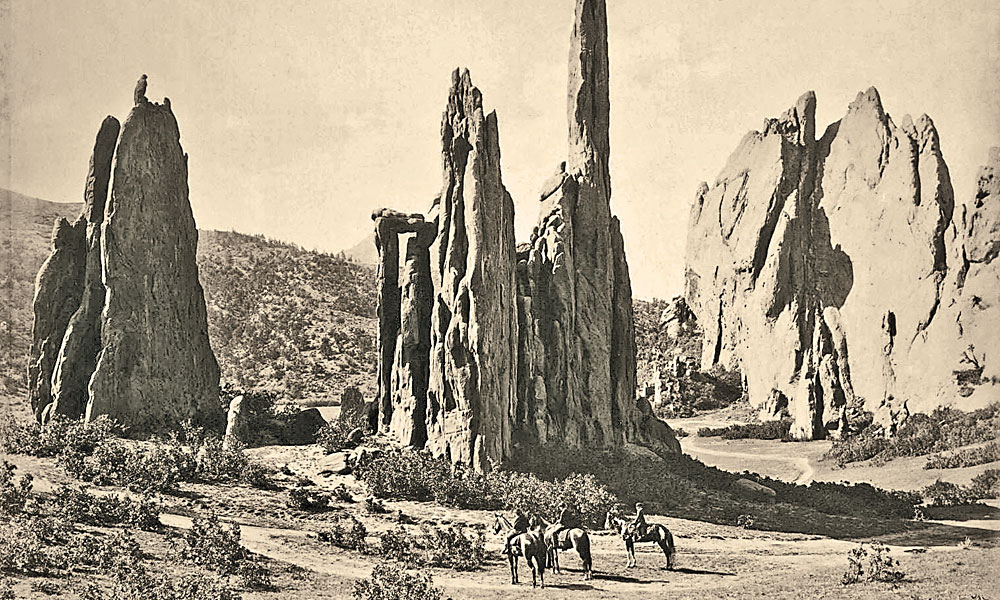

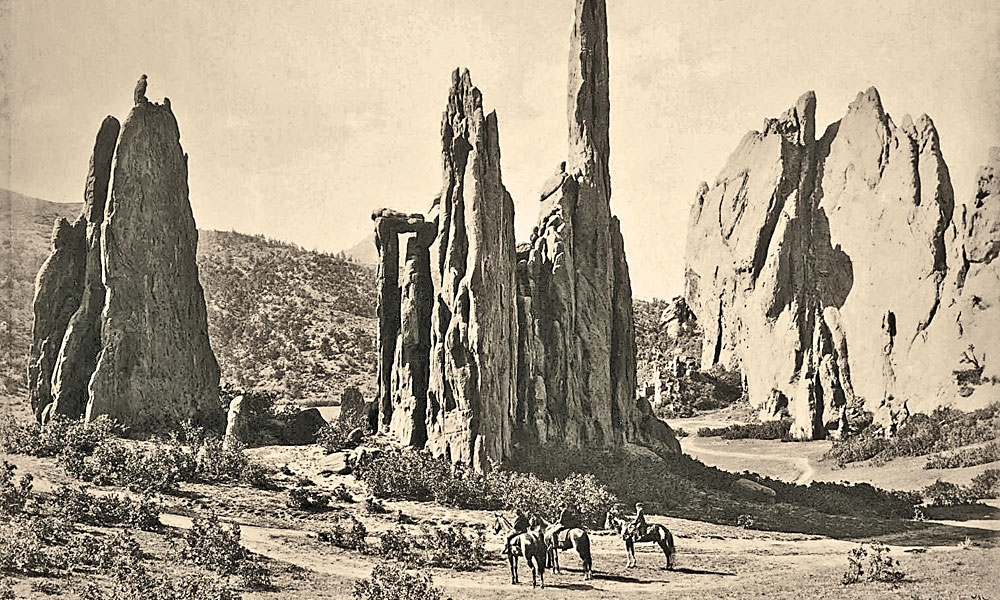

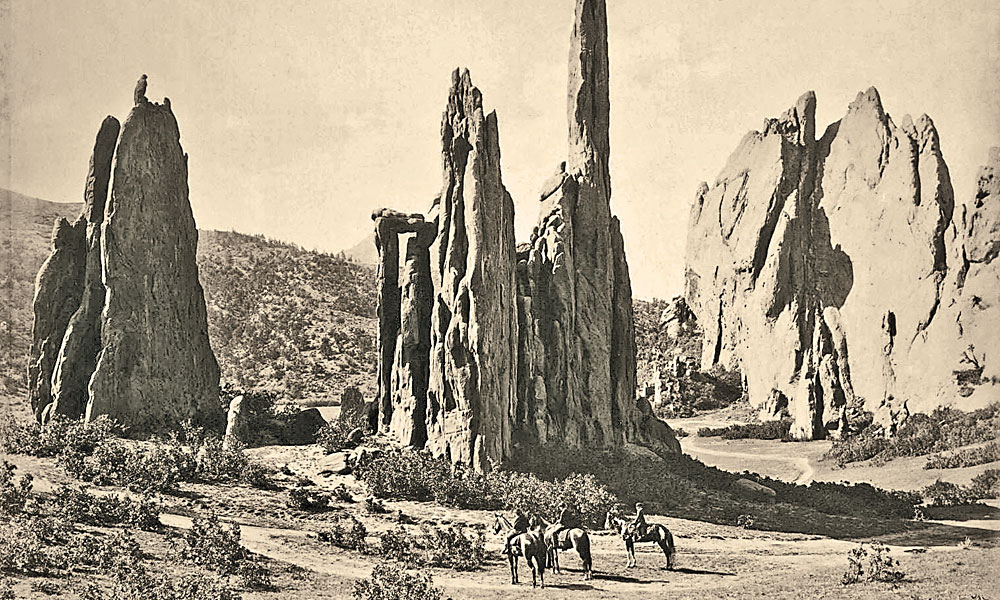

Hayden spent most of the 1867 and 1868 field seasons in Nebraska, with some time in Wyoming and brief forays into Colorado. He went on a whirlwind geologic reconnaissance of Colorado in 1869. His written description of this trip, in the Annual Report for 1867–69, reads like a travelogue from an arm-waving geologist talking from a fast-moving train through the landscape. His brief trek through Colorado, however, set the stage for the much more rigorous and organized survey of the territory prior to Colorado becoming a state on August 1, 1876.

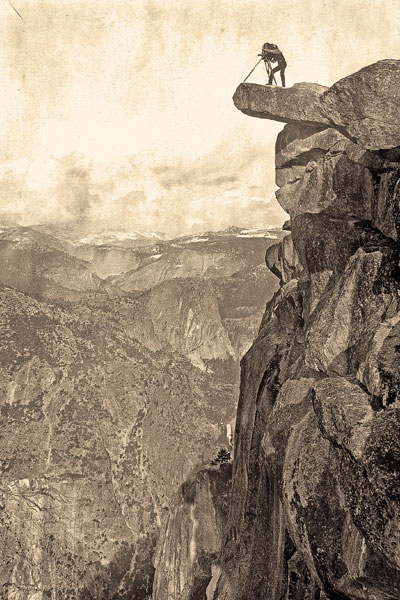

Much of the intervening time between Hayden’s first tentative work in Colorado and the start of his major work there in 1873 was spent in Wyoming, especially surveying the greater Yellowstone ecosystem, including the Grand Tetons and the future Yellowstone National Park. Hayden did not “discover” Yellowstone and its environs, but his survey’s work there made a huge impression back East. His 1871 field season results went far in promoting Yellowstone as the site for the first national park in U.S. history. By March 1, 1872, Congress had passed the Yellowstone Park Act, and Hayden was readying for his second field season there.

After the stunning successes of his Wyoming expeditions, after the majestic paintings of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River by survey artist Thomas Moran, after the designation of Yellowstone as a national park, Hayden abruptly changed locales. He decided that Colorado was the next best place to concentrate his efforts. He wrote: “The prospect of [Colorado’s] rapid development within the next five years, by some of the most important railroads of the West, renders it very desirable that its resources be made known to the world at as early a date as possible.”

This long-term, meticulous survey went down in history as the only one of a single state or territory explored in such depth. The scientific research done here made Colorado the most intensively studied place in the entire West, with the possible exception of California. The Atlas of Colorado that Hayden’s survey produced lifted up Colorado as the envy of every other state or territory and many foreign governments.

Although the Colorado atlas was not published until 1877, maps from Hayden’s tour de force of geographical efforts made their way to our nation’s first world’s fair, the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. His survey offered much more than a geological or geographical description of Colorado and the West. Hayden and his scientists and topographers looked at the land in all its varied facets. They described water resources, energy potential, agricultural promise, tourism attraction and esoteric natural history phenomena. They mapped the land and gave shape to many a dream.

Thomas P. Huber is a professor of geography and environmental studies at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs. This is an edited excerpt from Hayden’s Landscapes Revisited: The Drawings of the Great Colorado Survey written by Huber and published by University Press of Colorado in 2016.