What can you tell me about a fight between Wild Bill Hickok and some soldiers?

Joe Manriquez

Whittier, California

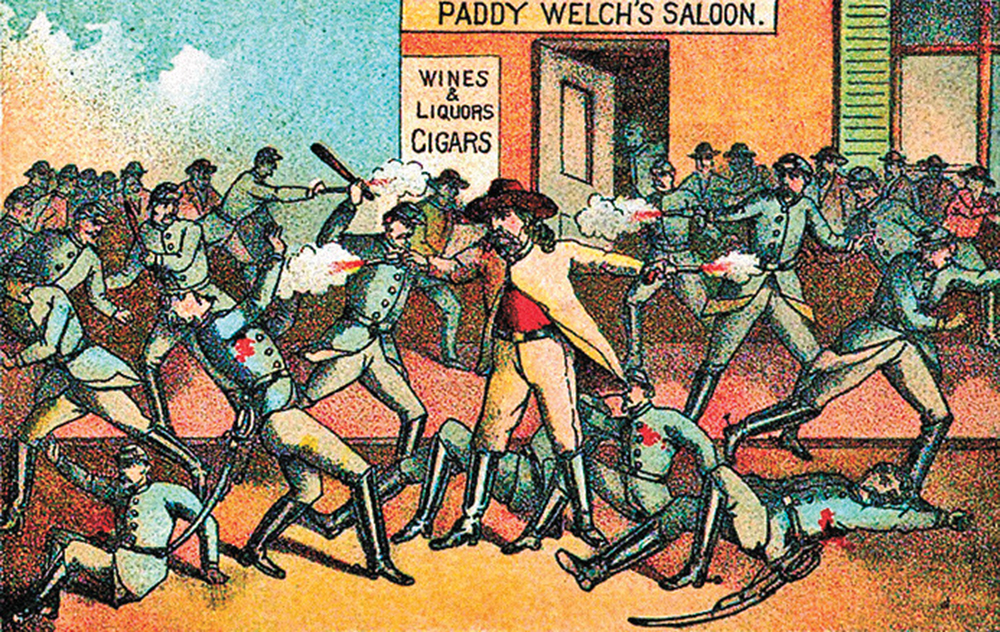

It took place on July 17, 1870, at Paddy Welch’s saloon in Hays City, Kansas. A couple of drunken troopers from Custer’s 7th Cavalry jumped Hickok. Jeremiah Lonergan, a pugilist of local renown, ran up and threw his arms around Hickok, pinning his arms and wrestling him to the floor. Meanwhile, John Kile pulled his Army issue revolver out from inside his blouse, stuck the muzzle in Hickok’s ear and pulled the trigger. Fortunately for Hickok, it misfired.

As the three men grappled on the floor, Hickok was able to draw his weapon and fire a shot into Lonergan’s knee, which forced the soldier to release his grip. Hickok then fired twice, mortally wounding Kile. He died at Fort Hays the following day.

— True West Archives —

Unsure of how many other troopers might join the fray, Hickok made his escape by jumping through a window. He went to his room, grabbed his Winchester and a hundred rounds of ammunition and hid out in the Boot Hill cemetery. The next day he headed for the Big Creek Station and boarded a train leaving town.

The military did not pursue charges because the two soldiers were off duty at the time and they had been involved in a barroom brawl. Longergan recovered but was later killed in another brawl.

As the years went by, the story of the fight in Paddy’s saloon grew with each telling—until James Buel had Hickok fighting 15 soldiers, killing three, wounding two and suffering seven wounds himself. Buel’s version also had General Phil Sheridan ordering Hickok brought in “dead or alive,” which was a tall tale.

Is there a source that gives the location of stagecoach robberies in Arizona?

David Vorie

Oatman, Arizona

Between 1875 and 1903, there were 129 stage robberies in Arizona—and five of them involved two coaches each. Contrary to the movies, in which mounted men chased down a stage and robbed it, only three were robbed that way. The rest were robbed by highwaymen afoot. They’d select a site where the stagecoach had to slow down and they’d walk up to the vehicle with guns drawn. More than half the stage robberies remained unsolved.

More than 200 people were engaged in the stage-robbing business in Arizona. Only 80 were identified—79 men and one woman.

The worst areas for stagecoach robberies were around Tombstone-Bisbee and the Black Canyon Stage Line between Phoenix and Prescott that follows I-17 today.

Check out Richard Patterson’s Historical Atlas of the Outlaw West. You might also want to contact Wide World of Maps in Phoenix (602-279-2323). It’s a good source for old maps of Arizona.

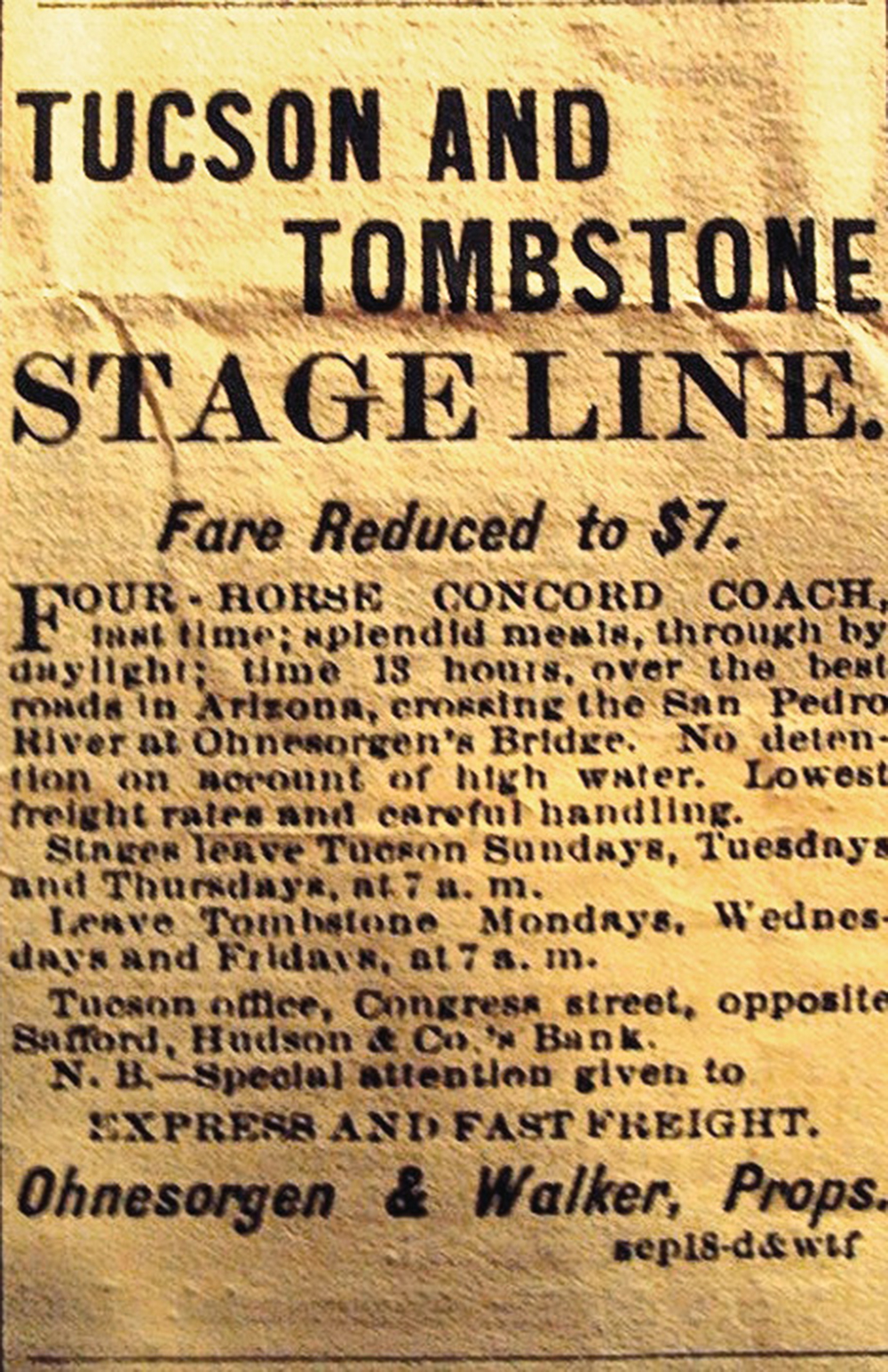

stage line in the 1897

Tucson Daily Citizen.

— True West Archives —

Why do most stories about the Trail of Tears talk only about the Cherokees and ignore what happened to the Creeks?

Paul Gomez

Midland, Texas

Funny you should bring that up. I have an ancestor who was on the Creek Trail of Tears. Their story is every bit as tragic as that of the Cherokees. The Creeks were one of the most powerful tribes in the Southeast. In 1836, they were exiled from their lands by land speculators and trespassers and even betrayed by some of their own leaders. Some 22,500 Creeks were forced from Georgia, Alabama and Florida and marched in chains to Oklahoma. My ancestor was adopted by a family in Arkansas; many Creeks gave up their children, fearing a much worse fate awaited them in what would one day become Oklahoma.

— True West Archives —

How often did Indians take captives?

Pete Winstanley

Maltby, South Yorkshire, England

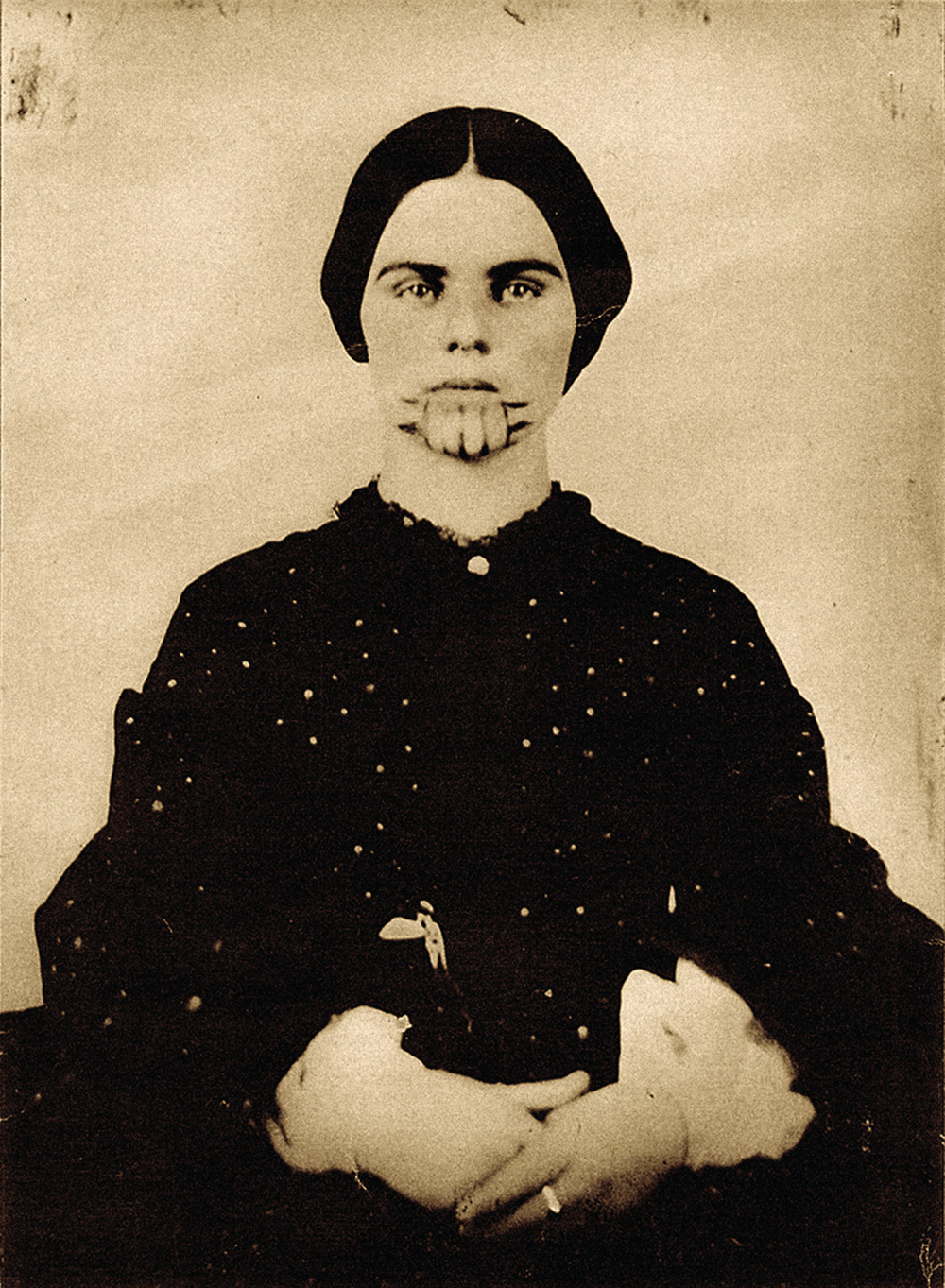

From the earliest days of the American frontier, the taking of captives was a common practice. Adult men were rarely if ever taken alive, but boys often grew up in the tribe and chose to remain. Same with little girls and young women. Some of the captives were later ransomed, and few were rescued by troops. And rescued is the right word, for life as a captive could be horrific. There were dozens of accounts of rape, beatings, abuse, enslavement, disfigurement and other acts of brutality. It was not a pretty picture.

Books on captives include A Fate Worse Than Death by Thomas Goodrich. Another is Lynn Bailey’s Indian Slave Trade in t he Southwest. According to Roy Young, Wild West History Association vice president, two of the best are The Boy Captives by Clinton L. Smith and The Captured—A True Story of Abduction by Indians on the Texas Frontier by Scott Zesch.

Marshall Trimble is Arizona’s official historian and the Wild West History Association’s vice president. His latest book is 2018’s Arizona Oddities: A Land of Anomalies and Tamales. Send your question, with your city/state of residence, to marshall.trimble@