Has one of the most famous of lost mines been found? Will the home of a lowly

javelina turn out to he the treasure cave of the Santa Ritas? The chances are good!

For the past couple of years I’ve been sitting on a real hot “lost mine” yarn, and don’t think it hasn’t been a temptation to cut loose and tell ole Joe Small’s readers all about it, but the stakes were far too high to risk a pre-mature disclosure of the find that Lady Luck tossed right smack into my lap.

You see, I’ve discovered the famous Planchas de la Plata lost silver mine! What’s more, I have it tied up real tight—at least, as tight as a gringo can tie it.

The story of Planchas de la Plata is known to every serious hunter of lost mines. For those unfamiliar with it, I’ll quote the early-day historian, R. J. Hinton, in his 1878 book, Handbook to Arizona:

Then came the revolution in Mexico. The republic was established, the Jesuits banished, and their church property confiscated. The Tumacacori Mission was abandoned, and naught remains of their history and doings, as known to the world, but tales handed down from generation to generation, and one or two books, which speak of the Salero, Tumacacori and Planchas de la Plata mines. The Salero is in the Tyndall district, the Tumacacori has never been found, and the Planchas de la Plata, or placers of silver, are located some twenty miles southwest of here (Tumacacori) stretching across the boundary line.

Apostolic Labors of the Society of Jesus, published by one of the most illustrious members of that order, is given the following account of the discovery of silver and gold in the Santa Rita range of Arizona: “In the year 1769 a region of virgin silver was discovered on the frontier of the Apaches, a tribe exceedingly valiant and warlike, at a place called Arizona, on a mountain ridge which hath been named by its discoverers Santa Rita.

“The discovery was unfolded by a Yaqui Indian, who revealed it to a trader of Durango, and the latter made it public; news of such surprising wealth attracted a vast multitude to the spot. At a depth of a few varas masses of pure silver were found in a globular form, and of one or two arrobas in weight. Several pieces have been taken out weighing upward of twenty arrobas; and one found by an inferior person attached to the Government of Guadalajara weighed 140 arrobas. Many persons amassed large sums, whilst others, though diligent and persevering, found little or nothing. For the security of this mass of treasure the commander of the Presidio of Altar sent troops, who escorted the greater bulk of the silver to his headquarters, whereupon this officer seized the treasure as being the property of the Crown.

“In vain the finders protested against this treatment, and ap-

pealed to the audience chamber at Guadalajara; but for answer the authorities referred the matter to the Court at Madrid. At the end of seven years the King made the decision, which was that the silver pertained to his royal patrimony, and ordered that henceforth the mines should be worked for his benefit. This decree, together with the incessant attacks by the hostile Indians, so discouraged the treasure hunters that the mines were abandoned, as needs must be until these savages are exterminated.”

Not all the priestly historians write so smoothly of this transaction, which, by the way, is commented on in every work upon Mexican mines since written and published. The reader, who should desire to see how deep in gall a Castilian may dip his pen on the same subject, should peruse a work entitled Los Ocios Espanoles, or the documents yet existing in the archives of Pimeria Alta,

written by Jesuit Fathers, who were despoiled by this act of the King. Curses loud, strong and binding were showered upon the royal robber, and thenceforth such discoveries were most carefully locked up in the breasts of the Fathers, until at last the cream had been properly skimmed off. This was the real beginning toward uncovering the riches of the Santa Ritas.

Then the Apaches drove out all gold seekers, and this treasure book of nature was sealed, down almost to the present day, in the blood of explorers and prospectors, gentle and simple, Mexican and American. But as the old Padres were wont to say that the difference of one letter made a difference of millions of souls: ‘All men will dare death for goldfew are they who dare it for God!’

In 1817, Dionisio Robles, a courageous inhabitant of the town of Rayon, fitted up an expedition of over 200 men, and proceeded to the Santa Ritas to discover these rich spots. They fought their way for seventy leagues, found what they believed to be the old workings, but which were only the marks of the first prospectings; and as the quaint old chronicles say that “Although throughout all their seekings they did find virgin silver, more or less, yet were not these large masses of treasure so readily obtained during the eight days of their stay; so that finally, after much loss of life, being daily and nightly beset with the savages, they did turn their steps homeward, being exceedingly harassed all the way; bringing home, indeed, a good store of treasure, but yet no single piece of pure silver weighing in excess of four arrobas. Yet…will it again and again be adventured until the savages become extinct. and the superior race possess the untold wealth imbedded in the mountains of Santa Rita.” So much for Hinton and the original designation of “Santa Ritas.’’

Down through the years, right up until today, hundreds of prospectors have tramped south-central Arizona searching for gold, silver, copper or anything of value. Success has smiled widely on a few; given a provocative wink to many; and turned up her nose at most. She never gave as much as a nod to all the gambisinos who hunted for Planchas de la Plata.

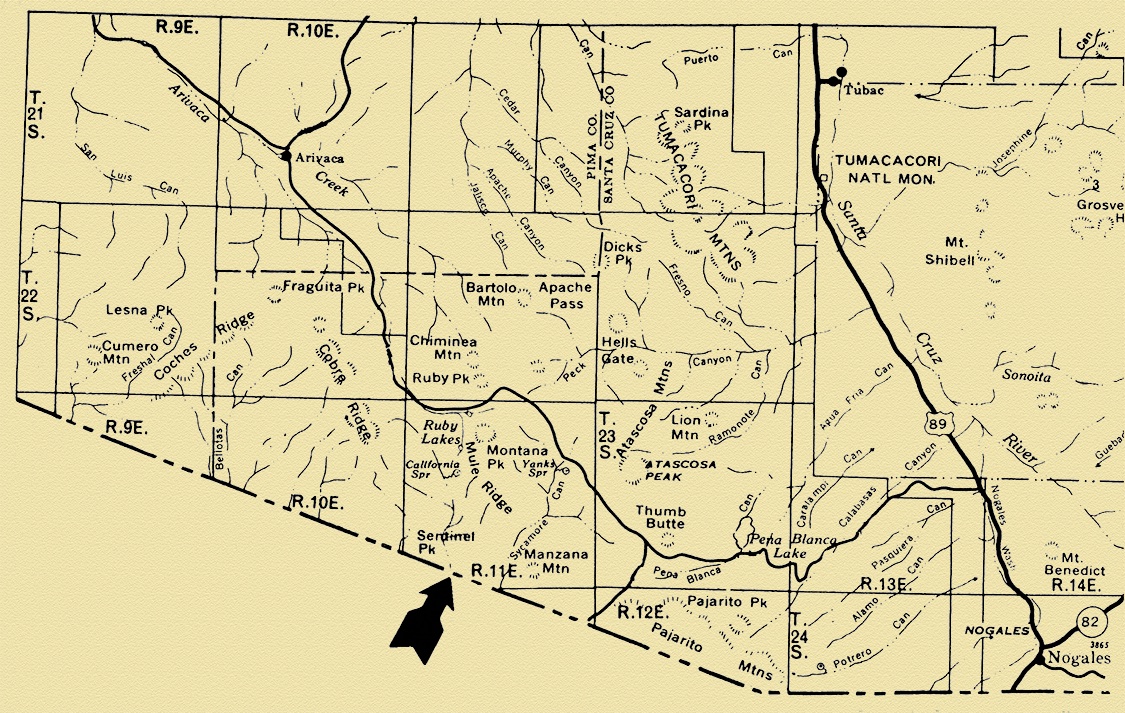

In the early days, all of the mountains surrounding the Tumacacori area were known as the Santa Ritas. Today they have been divided up into a dozen or so smaller ranges, but for the purpose of simplifying this story, we’ll use the original designation of “Santa Ritas.”

In 1960 I became in-

terested in a particular portion of Santa Cruz County and did quite a bit of prospecting, gold pan-ning, and general explor-ation south of the ghost town of Ruby, down what is shown on the maps as California Gulch, but is locally called Smugglers’ Gulch. Not only was the area a great gold and silver producer around the turn of the century, but it is heavy in history. Careful exploration will turn up the sites of many camps of yesteryear, graves of a family killed by Apaches, a cemetery which is reputedly the final resting place for nineteen United States cavalrymen who died fighting Mexican bandits, foundations of ‘dobe and rock buildings, and a host of other interesting relics.

February of ‘61 found me combining a prospecting trip with a hunt for javelinas (wild pigs) that are native to the cactusand mesquite-studded mountains along the International Border. You find the peccaries feeding on prickly pear during the first two or three hours of daylight, and sometimes again along about dusk. I’d been working west along the fourstrand barbed-wire fence that separates the two countries one morning, when I jumped a band of perhaps a dozen, busy with their breakfast. They dived down a small arroyo cut in solid rock, and I followed, hoping to draw a bead on the big boar that led the pack.

The arroyo soon became a small canyon and, as I picked my way through the rocky debris in the bottom, I glimpsed a pig disappearing into a small hole in the south wall of rock. Not knowing as much about the habits of these animals at that time as I do now, I sat down to wait for it to reappear. Perhaus I’d still be waiting had I not noticed a cross cut into a rock that lay close to the opening in which my quarry had chosen to hide. Those marks transformed me from pig hunter to treasure hunter in less time than it takes to tell.

I had long known this country was once the stomping grounds for miners, Indians, settlers. Even a Chinese gardener had eked out a living selling produce to the miners. There are all sorts of legends regarding treasures, both buried coin and bullion, as well as lost mines, to be heard around the fire in most any native’s home. I wasn’t quite prepared, however, to find this definite evidence of the ancient Padres. Yet here it was, lying at my feet, so to speak.

Examination of the immediate area disclosed that the small horizontal slit of a hole into which the javelina had disappeared was the single possibility of a “working.” Perhaps eighteen inches high, and twice as wide, the opening appeared to slope downward. This pretty well decided me that I had happened upon the entrance to an old tunnel, for they always fill from the bottom, with any opening left along the roof. There was no sign of an ore dump, but the nature of the tight little canyon is such that snows would funnel water across the place where a dump would have been, thus washing away any trace of such work.

Yes, I’d happened upon an old mine, or at least a prospect, but there were a couple of disturbing elements about the situation. The immediate problem was that I knew this hole to be inhabited by a peccary, and I had little stomach for tackling one of the vicious tuskers hand-to-hand. Secondly, the tunnel appeared to go almost straight south, right into Mexico, which was certain to compound the difficulties were I to have a real mine.

I returned to camp, traded rifle for camera, herded the Jeep as close to the place as I could, then climbed through the cactus to the canyon. After making a couple of pictures of the rock with the cross, I lugged it back to the vehicle and into camp, where it remains today in front of my ‘dobe. About twenty inches high, fourteen wide, and five thick, it makes a pretty good load. The cross is chiseled deeply.

Little contemplation was required as to the course the discovery must take: Were I to tell a single soul, the word would get out and I’d be hard put to run off potential claim-jumpers. The only thing to do was to go ahead and explore it alone and in utmost secrecy. I did exactly that, and it appears that my lone hand has paid off.

It was almost two months after the pig led the way to the tunnel when I slipped down there late one afternoon, enlarged the hole a bit, then wriggled head-first into the dark and longabandoned cavity. After the first twenty feet the hole opened up enough that I could ‘walk upright. It, is perhaps seven feet high, five to six feet wide, and the floor is covered with considerable loose rock and evidence of many years’ habitation by javelinas (although I’ve never met another there). Driven to the south and a trifle east. the adit ends perhaps sixty feet south of the border fence. It terminates in a good-sized room from which considerable ore evidently had been removed. A stope goes up at one corner, appearing to have been abandoned while still in ore. Another corner contains an inclined shaft or winze that went down on ore.

Subsequent trips to the mine, coupled with considerable sampling, turned up some very interesting information. The ore is not in any great, continuous mass, but seems to run in several veins that widen, pinch down, then open up again. From time to time I picked out pieces of native silver in uneven sheets or small spheres. The high-grade became more plentiful in the hanging wall as I worked my way farther and farther down the incline on every trip to the mine.

By the last of April 1961, I had gathered enough samples to get a representative assay and took them to Hugo Miller, an excellent assayer, in Nogales. Rich beyond my fondest hope, the assay showed values in gold, silver and copper totalling $19,924.22 per ton-almost pure silver. True, I had hand-picked the very high grade material but, by the same token, that assay was made at a time when silver brought about thirty cents an ounce less than it does today. Truly a fabulous property.

Soon after the report came, I laid out and filed a claim on the immediate area of the tunnel, using the U.S.-Mexico border fence as the southern boundary. Then followed a lot of exploratory work. The ore body appears to be richer with depth, and I’ve moved enough of the loose rock that all but blocks the incline to the lower level and have gone down over eighty feet. What is below is anyone’s guess. I have hopes that in the lower reaches of the mine will be tools, lamps or something to identify the early workers.

All of these explorations have been conducted completely alone, for I have no desire to be plagued by would-be claim jumpers, the idle curious, or so-called “friends.” Thus far I’ve removed no material other than samples, and have not enlarp:ed the entrance to any great extent. Every photo with which this article is illustrated was made by a remotely controlled shutter, or a self-timer connected to the camera. It has been a lonely and dangerous game, but in handling it this way I feel my secrecy will pay off.

In order to legally hold a mining claim, mineral in place must be shown within ninety days of filing. After that, the claim-holder must spend at least $100 in cash labor on the claim every year. In order to comply with these requirements, I have located a gold-bearing quartz vein on the same claim. The discovery work was completed, and each year more than sufficient assessment work has been performed on it. The proper Affidavit of Proof of Labor is recorded every year, with the claim being known as “Casas Piedras.”

As in all such things, there is a serious1 drawback. In this case it is the fact that while the entrance tunnel begins on the United States side, it goes directly under the International Boundary and the main ore deposit appears to be located in Mexico. I’ve wracked my brain and grasped at straws trying to find a legitimate way in which I can mine this property.

One thought was the oft-repeated tale of a so-called “buffer zone” that some say separates the two countries. Proponents of this line maintain that there is a 200-foot wide strip of land on the Mexican side of the fence that actually belongs to the United States. It was supposedly surveyed that way to hold down any disputes about the exact location of the line. However, inquiries in Washington brought only the information that for all practical purposes, the fence is the border.

Perhaps I could work the ore body by careful high-grading. This would certainly result eventually in serious trouble, for not only would I be stealing from Mexico, hut smuggling contraband into the States. In fact, that would be the most foolish move I could make, for I’d have to disclose the origin of the ore in order to sell it, and high-grade such as this would bring many questions. On top of the disposal problem is the certainty of detection by the Border Patrol. I’ve been around them long enough to know that no one puts anything over on them for any length of time.

Judicious inquiry convinced me that a Mexican national as a partner is the onlv answer. As a result, I’ve taken in an old compadre on the part that lies South of the border. He’s honest, smart, and knows mining. We have made legal arrangements with the land owner and soon expect to cut into the tunnel from the Mexican side. The Mexican Government takes about fifty percent right off the top of the gross mineral production, it is true, and for a United States citizen to engage in such a business in that country he must have a Mexican national partner who owns fifty-one percent of the partnership, but even this and the associated mining expenses should leave a husky piece of change for me.

Minor explorations south of the border subsequent to the original discovery, turned up a couple of Mexican “ovens” such as were used ages ago in removing metal from high-grade ores. Using my metal detector, I learned that one of these ovens contained metal. Dismantling the crude smelter disclosed a fourteen-pound piece of nearly pure, smelted silver. Today this plate of silver is on exhibit in a Mexico City museum. At any rate, it supposedly is, for I turned it over to certain “authorities” in that country as part of the deal that is to let me mine the property.

Still another possibility presents itself—for the vein may well run north across the border and into the United States. A core-drilling program might pick up an ore body, but for the moment I’m preparing to give it a going over with a mineral-metal detector made especially for this job. I have the instrument here in Tucson, and, after a bit of practice with it, will head for the border country.

Why do I believe this is the lost Planchas de la Plata Mine? There are many reasons: the locale is right, for it is approximately twenty miles southwest of Tumacacori and straddles the border; the cross cut into the stone and used to mark the mine definitely indicates that it was church property; and the nature of the ore itself is similar to that described in Hinton’s account. Granted, I’ve found no two, three or fourarroba pieces (an arroba is twenty-five pounds), but I have done no actual mining there and you cannot expect to find the big pieces just sticking out of the veins waiting to be plucked by the first-comer.

Yes, I’m convinced I’ve found a “lost mine.” No, I don’t need another partner. I want no one snooping around the property and, as a legal mining claim, it is my property, so I’ll discourage anyone I find there.

I have hesitated to tell this tale, for a lot of luck and hundreds of hours of hard and dangerous work on my part have been involved in bringing the property to its present status. Now all I want is a chance to mine it and cash in on my find. However, I know that I’m now legally protected from the vultures that hover over every small mining venture, and believing this discovery will be of interest to readers of True West, I’ve decided to put it down on paper.