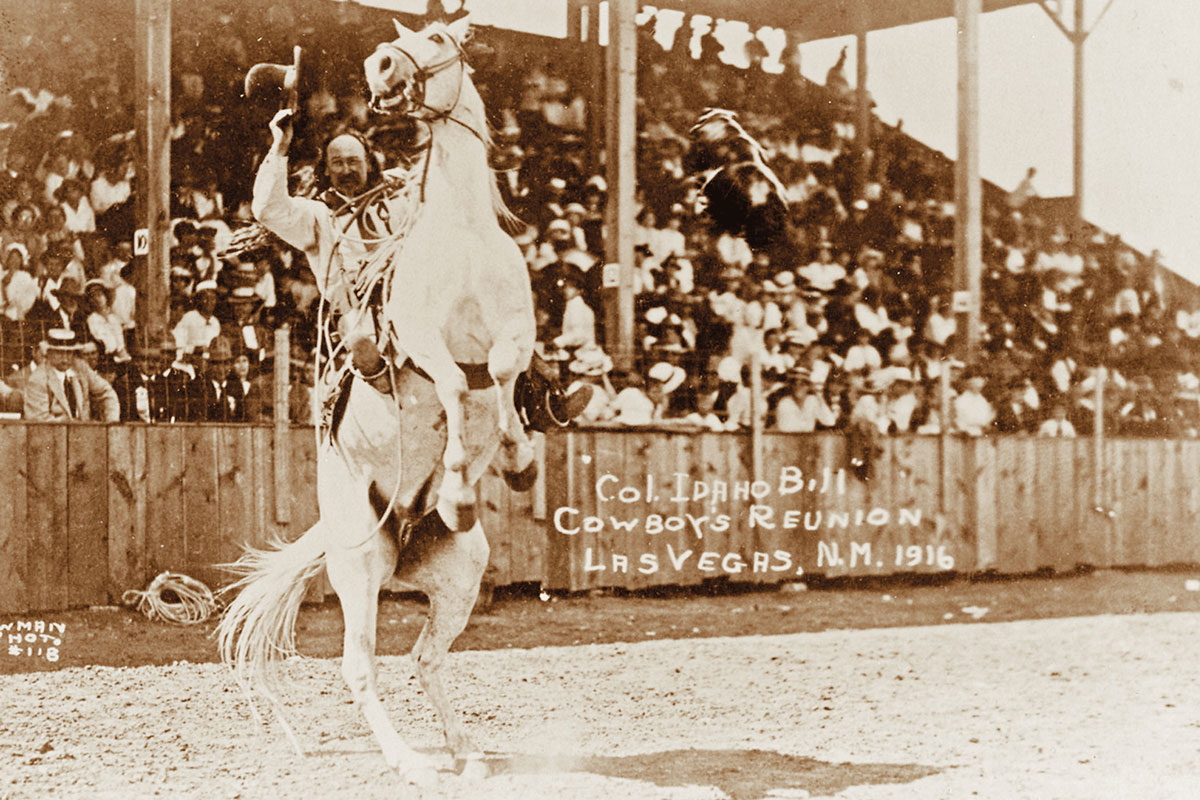

— All Images Courtesy Adams County Nebraska Historical Society Unless Otherwise Noted —

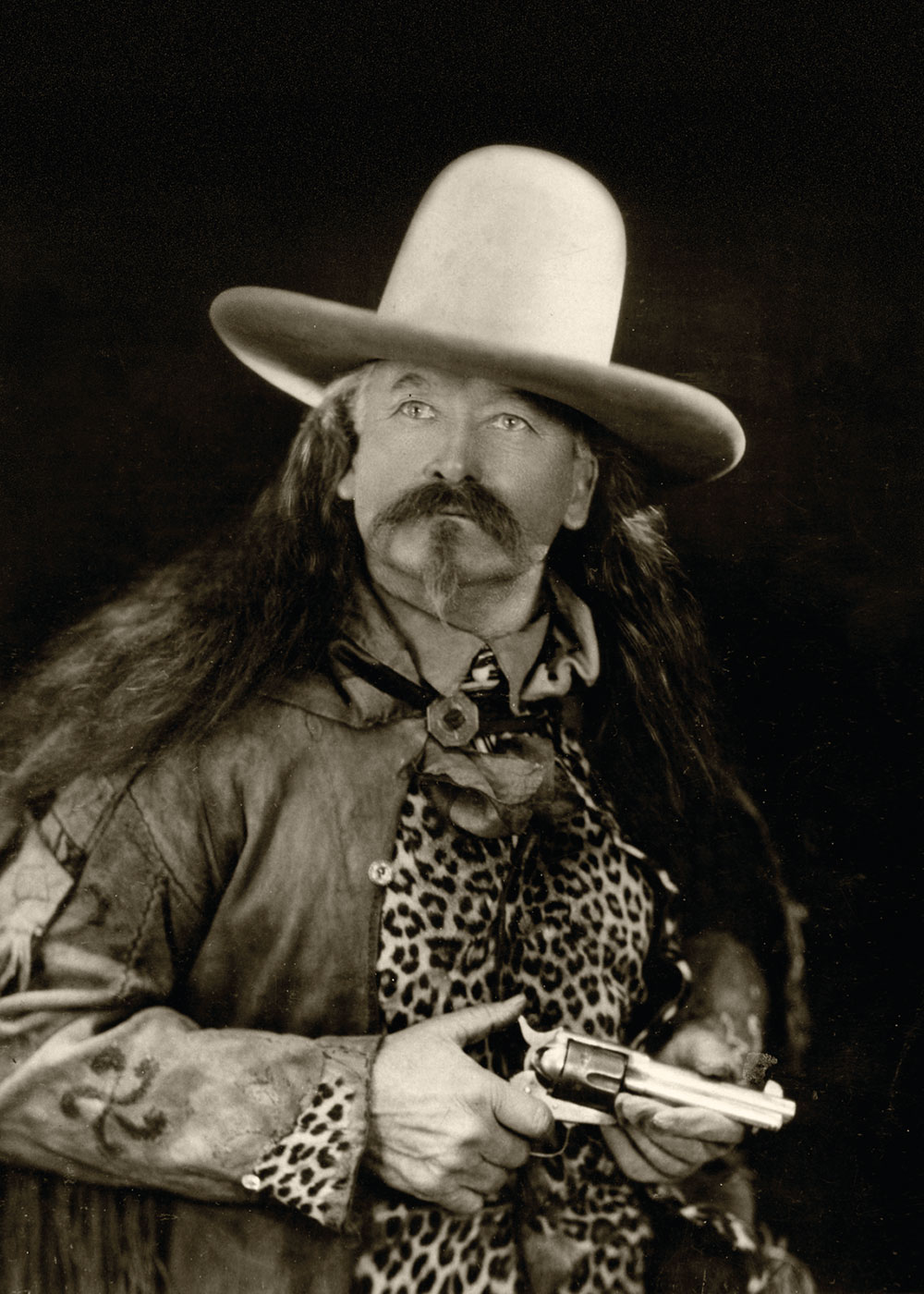

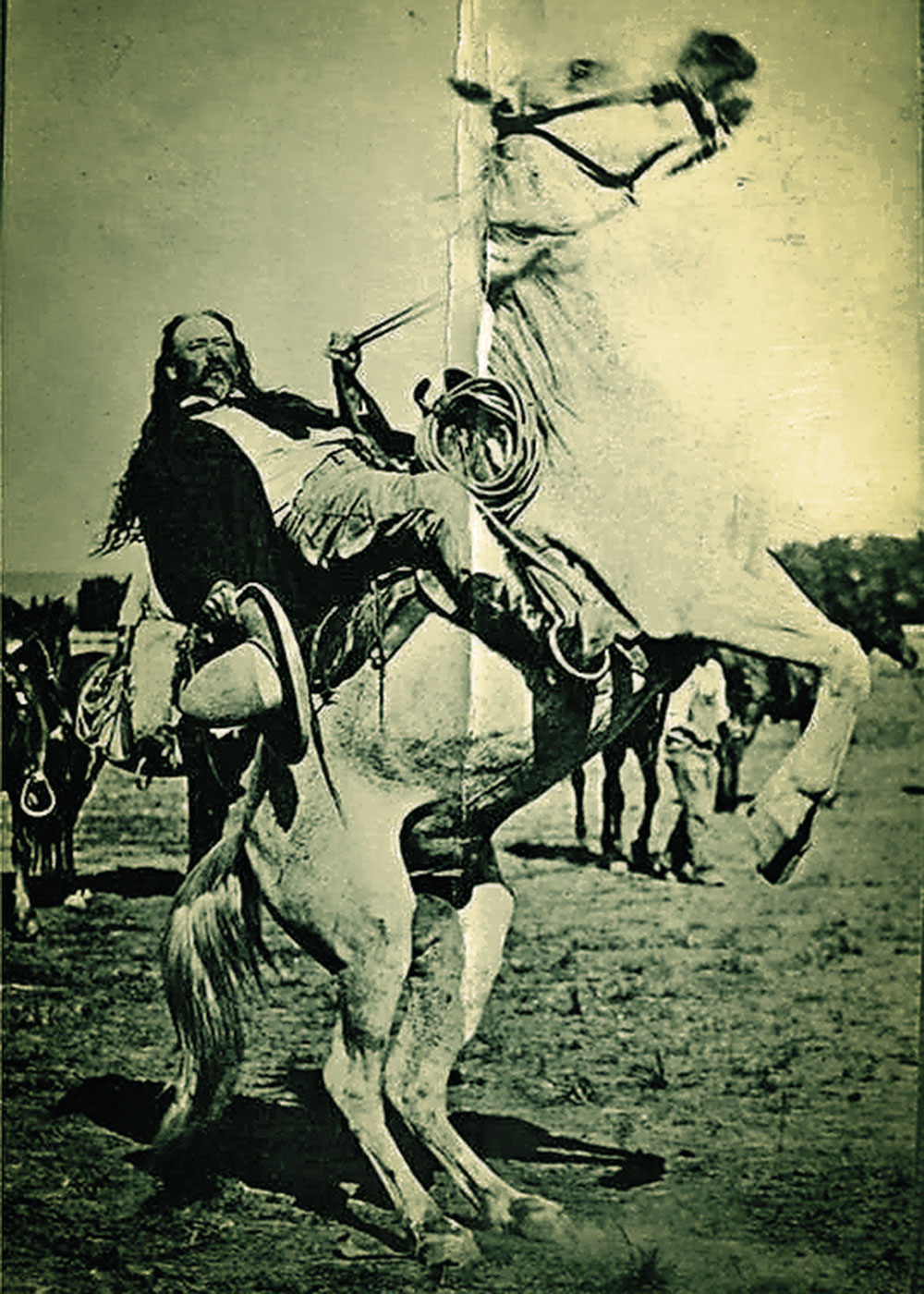

Welcome to the legendary world of Barney “Idaho Bill” Pearson— rancher, bronco buster, wild animal hunter, showman and friend of Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill, Pawnee Bill, Billy the Kid, Deadwood Dick, Luther North, Theodore Roosevelt and President Calvin Coolidge. He was crushed by a horse, jailed for murder, sued for wrongful death and divorced by his unfaithful wife. A natural showman, he never let the truth get in the way of a good story.

As a kid, I used to stare longingly at a certain Colt Single-Action Army .45. The old revolver was mounted behind glass, safely away from my sweaty little hands, among the firearms collection at the Hastings Museum. A fine old Colt always demands attention, but it was the inscription on the ivory grip that fired my imagination: From Buffalo Bill to Idaho Bill 1916. We all know who Buffalo Bill was, but who was Idaho Bill? Here’s the story of man who was called many things, not the least of which was colorful.

Bonde R. Pearson, pronounced “Boonduh,” was born in Sweden in 1868. He was four when his family immigrated to America. In December 1872, father Knut settled the family southeast of Hastings, Nebraska, near the old Oregon Trail.

Bonde had a natural talent with horses, making it easy for Knut to teach him how to ride as a youngster. He left home at age eleven to work on a ranch in Kansas near the Republican River. He spent the following three years working on a ranch near Fort Kearny, Nebraska, where he helped break horses. In the 1880s, 15-year-old Bonde, by then called “Barney,” worked on J.H. Bart’s Hat Ranch near Pocatello, Idaho.

In the meantime, Knut added to his landholdings by purchasing a small ranch in the Snake River Valley of Idaho, perhaps on the recommendation of his son. Apparently, the elder Pearson was concerned that his son would fall in with those who “threw a long loop.” He promised Barney an overseas trip if he would manage the Idaho ranch until cattle went to market that fall of 1886.

Although he had a reputation as a first-class bronc rider, Barney had less success riding the ocean waves on a ship. “I kept losing my temper, along with my meals, until I got used to it,” he said later. He walked the streets of Paris in his untrimmed hair, goatee, Stetson, boots and holstered six-shooter. Even though he was relieved of his revolver by a local gendarme, he kept the gun belt on. “I guess the Frenchies was scared I’d get a wild hair in the butter and drop one of them! Maybe even thought I’d scalp one of them, who knows?” Barney reported. Pearson hired on with various American cowboy exhibitions traveling Europe, but in 1887, there being no place like home, he re-crossed the Atlantic in a tramp steamer.

Back in Nebraska, Barney became a renowned horse-breaker and dealer in bad broncs which he rented to cowboy contests. Pearson delivered the first horses to the Pueblo, Colorado, fire department. While in Pueblo, he met and married Sarah “Sadie” Tifty in May 1891. Daughter Millie was born later that year.

The family moved into Hastings so Barney would be closer to a rail shipping point for his horses. By the turn of the century, Barney, complete with boots and 10-gallon hat, was becoming well known in the West. When he became known as “Idaho Bill” is unknown, but perhaps he patterned himself after friend, William F. Cody, since Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performed in Hastings six times between 1886 and 1915.

Barney’s business of supplying broncs to rodeos and Western exhibitions was successful, but he decided to produce the exhibitions himself with hired hands. His first big show was in the Tatersall Armory in Chicago. He offered prizes of a 1,000-dollar and a 500-dollar bill to any cowboy to ride his worst bronc.

In 1902, he sold a carload of horses to Hastings stockman and livery employee Walter McCulla. To celebrate the sale, McCulla was a dinner guest of Barney and Sadie. Later the same year a bronco fell on Barney at an El Paso rodeo. He asked McCulla to look after his horses while he recuperated. McCulla did even more than that. Barney soon learned that Sadie had been seen with him late at night. She filed for divorce in 1903, but she and Barney reconciled before going to court.

Barney continued to find McCulla with Sadie and he even complained to Mrs. McCulla. Soon after, Hastings police broke up a fight between the two men, with McCulla being hauled off to the calaboose for assault and carrying a pistol. The affair continued, however. Finding the two together yet again, at the business end of his six-shooter, Barney forced McCulla on his knees, to swear to end the relationship.

Stepping off the train late on the night of July 28, 1906, Barney walked to his home, where he saw a party in progress. McCulla was there. Infuriated, he retrieved a shotgun from his father’s home nearby, and asked a local reverend to accompany him to his house. While the reverend tried looking into a window, Barney went to a big window at the rear of the house. He brought the shotgun up and fired through the glass. McCulla nearly went down but caught himself and ran out the front door. He soon collapsed and was helped to the nearby home of attorney M.A. Hartigan.

Police were called to the Pearson home to investigate. They were well aware of the ongoing affair. Sadie was less than truthful with them when asked who was at the party. They observed a partially empty beer box near the blown-out north window and the damaged front door and furniture.

The policemen were soon summoned to Hartigan’s house where Dr. C.V. Artz treated McCulla. It didn’t take Sherlock Holmes to connect McCulla’s wounds with the shooting at the Pearson home, and Barney became the prime suspect. The next morning Barney found himself in the Adams County jail. The charge of “maliciously shooting with intent to kill, wound or maim” had to be dropped when Walter McCulla succumbed to his wounds. He died that afternoon with his wife and four children at his side. Barney was then charged with murder.

While waiting for the trial, Barney was sued by McCulla’s estate for $5,750 in damages. Sadie had filed for divorce claiming that he was unmindful in his duties as a husband, and on one occasion pointed his revolver at her face and threatened to kill her. Out on bond, Barney was shot at late one night behind his house as he stabled his horse. Neighbors heard the shot, but neither Barney or Sadie would comment.

A verdict of not guilty was brought after a second trial in May 1907. Barney “Idaho Bill” Pearson was a free man. Back to work, he supplied 19 “outlaw” horses to an exhibition held at the Chicago Coliseum. Barney’s largest rodeo production was held in Dewey, Oklahoma, in 1912, where he met Will Rogers. The two would meet again in 1932, when both were asked to speak at the Adventurers Club of Los Angeles.

During a campaign visit to Hastings in 1912, Theodore Roosevelt noticed Idaho Bill and waved him to his car. He’d met Barney at Cheyenne and never forgot him. T.R. insisted that he ride to the train station with him.

In Chicago, Barney made connections with the Essanay Film Company, which was founded in 1907 by George Spoor and Gilbert “Broncho Billy” Anderson. The company hired Pearson, the owner of Idaho Bill’s Cheyenne Frontier Exposition and filmed his performers to provide realism for their 1908 film, The James Boys in Missouri.

— Courtesy Monty McCord Collection —

Within ten years, Barney was lassoing wild animals to sell to zoos around the country. In 1920, he was very noticeable while driving his Model T in Omaha with a bear eating lemon stick candy in the back seat. The stunt provided him with several lecture appearances in the city.

During July 1931, an El Paso, Texas, newspaper reported that Idaho Bill was visiting again and stated, “He carries a .45 Colt pistol given him by Buffalo Bill…”

During World War II, Idaho Bill used his showman skills to help boost sales of war bonds. By then he traveled in style in a Cord convertible and a Lincoln Zephyr.

Barney was living in Los Angeles when he died on November 28, 1942. His daughter, Millie, returned his body to Hastings for burial in Parkview Cemetery, right beside his ex-wife Sadie. Matching, modestly appointed headstones mark their graves.

Barney “Idaho Bill” Pearson probably didn’t know Wild Bill, as he was killed when Pearson was eight. He probably didn’t know Jesse James or Billy the Kid, either. But, like his father’s homestead, most of Pearson’s claims proved up, and then some—leaving us with another rich bite of Western history.

Monty McCord is the author of Calling the Brands-Stock Detectives in the Wild West. This article is excerpted from the author’s book manuscript, Idaho Bill.