The Arizona Rangers were established as a territorial law enforcement agency in 1901 to curb the outlawry that was rampart in Arizona’s rural mountain country, especially in the rugged mountains along its eastern border with New Mexico and also along the Mexican border from Nogales east to Naco.

Their first mission was to break up gangs of livestock thieves. In 1903 the territorial governor even sent them to Morenci to break up a labor strike and again three years later to protect Americans at the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company in Sonora during a strike.

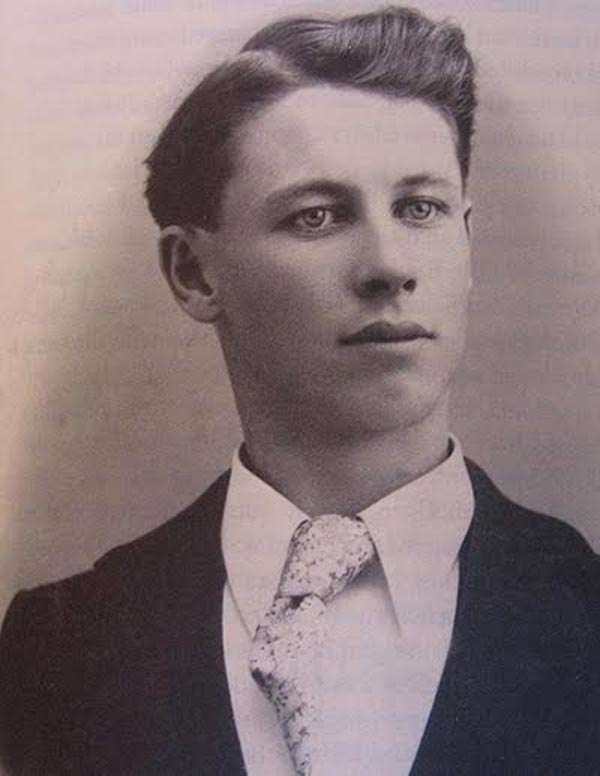

Jefferson Kidder was one of the most famous of the elite Ranger force that never numbered more than twenty-six men. He enlisted as a private in 1903. At the time Rangers were busy dealing with smuggling problems along the Mexican border. Kidder working as a line rider along the border with another Ranger, Fred Rankin. The two were receiving a 40% stipend from the Mexican government on all smuggled goods they recovered.

During one pitched battle with smugglers, Kidder wounded one of the smugglers while Rankin shot the horse out from another gang member. The smugglers fled, leaving some 10,000 rounds of ammunition and other contraband that was seized.

Most of the time Kidder was stationed in Nogales, Arizona where he was very popular with the locals. Once when he was transferred temporarily the Nogales newspaper wrote, “Jeff’s many friends here are sorry to see him leave this point, He is a first-class, level-headed officer and a gentleman.”

The two line-riding Rangers were not so popular with the Mexican line riders and police in Naco, Sonora. They’d become jealous of the success of the two and had even made death threats. This might be what led the trouble in Naco in 1908.

Also there were some hard feelings on the part of the Mexicans over the Ranger’s incursion into Mexico during the big strike in Cananea two years earlier.

In 1908 the new Ranger captain and close friend Harry Wheeler promoted Jeff to first sergeant. Wheeler an ex-Army man had also risen the ranks to lead the outfit.

Kidder’s father died in the previous year, leaving him with some inheritance and he bought a new, engraved Colt .45 with pearl grips. He spent a lot of time practice shooting and was the quickest draw and considered one of the best shots among the Rangers. He could also shoot equally well with either hand.

An incident in Naco occurred in 1906 when a dozen or so drunken hobos were creating a disturbance along the railroad tracks west of town. When Kidder and Sgt. Bill Sparks went down to break them up the revelers gathered around them and commenced to pummel the two lawmen to the ground while a group of bystanders stood by watching. When one pulled a knife Sparks drew his weapon, fired and hit the assailant in the hip. This took the fight out of the carousers and they were taken into custody.

On New Year’s Eve, 1906 Kidder was in another shooting, this time in Douglas where there had been a string of robberies and Kidder was temporarily transferred there to assist in quelling the outlawry. He and a local police office were patrolling the area around the roundhouse of the railroad when they saw a man come out of the building and hurry away.

When the Ranger called out to him the man turned and fired his pistol. Kidder drew his revolver and fired three times. One of the rounds slammed into the shooter’s head mortally wounding the man, a saloonkeeper named Tom Woods.

Kidder wanted a full investigation and requested a murder investigation on himself. A few days later the Ranger was exonerated in the killing of the suspect.

Kidder spent most of his Ranger career in Nogales, hounding smugglers, rustlers, gunrunners, fugitives and other lawbreakers. He was well-liked by the people of Nogales. Detractors referred to him in the border vernacular “rinche” and considered him arrogant. Rinches was a derisive term that referred to any lawman but more often to the Rangers. Kidder backed up his bluster with uncommon expertise as a pistolero. Those who knew him best regarded him with respect and affection.

On April 1st, 1908, Sergeant Kidder received a letter from Captain Harry Wheeler reminding him that his enlistment expired each April 1st and he was asked to meet Wheeler at Ranger headquarters in Naco to be sworn in for another year. He took his inseparable companion, a dog he called Jip across his saddle, along with a pack animal and rode east to Naco, Arizona, arriving on April 3rd. He then headed across the border to Naco, Sonora to meet with an informant coming up from Cananea. The Rangers had been ordered by Wheeler to stay out of the town because of the problems from the mining riot in Cananea in two years earlier, he feared they might be killed. Not wanting to appear aggressive, he took off his gunbelt and stuffed his pistol inside his coat.

Around midnight he was in a cantina talking with a dance hall girl named Chia seeking information. As he was leaving he checked his vest pocket and found his last silver dollar missing. He accused her of picking his pocket and she slapped him and yelled for the police who apparently were waiting outside the door burst into the room with pistols in hand. One fired, hitting Kidder in the stomach. He went to the floor, drew his .45 Colt and shot both policemen hitting one in the knee, the other in the thigh. That took all of the fight out of them.

Badly wounded and in shock he stumbled outside and headed for the border a quarter mile away. He found himself blocked by Winchester-wielding line riders who opened fire. His pistol empty. He reached the fence but was too weak to make it through the wire so he reloaded as the police chief, Victoriano Amador charged towards him. Kidder shot him in the side and held the others at bay until his pistol was empty again.

When Kidder shouted he was “All in” the officers charged, pistol-whipping him to the ground. He was dragged some fifty yards back from the fence, then pistol-whipped again. One attempted to shoot him in the head but was prevented from doing so by Chief Amador.

The Ranger was then taken to jail, robbed of his possessions and tossed into a cell with no medical attention. When word reached the American side they contacted Mexican officials and a doctor was called. Kidder was taken to a private home. Another doctor from Bisbee was allowed to see him. The prognosis was grim, his intestines had been perforated by the gunshot.

Kidder was interviewed by a reporter from the Bisbee Review and told his story while his faithful dog lay near his cot. “If anybody had told me that one human being could be as brutal to another as they were to me I would not have believed it.”

He seemed to hold on for a while but then his condition worsened and he died early that Sunday Morning, thirty hours after being shot.

When the Mexicans refused to release his body some 1,000 Americans threatened to march across the border. American fury was fanned by stories that Kidder had been set up by Mexican police who were jealous of his success against border outlaws. Finally the Mexican judge released his body and Kidder was taken to Bisbee, a few miles north of Naco. His skull had been so badly beaten that embalming fluid ran from his eyes and nose. Several ribs had been broken by kicks and the backs of his hands were scratched and blood-stained from trying to ward off his attackers.

When Captain Wheeler learned of his death he set out for Bisbee and at the funeral parlor told reporters “Jeff Kidder was one of the best officers who ever stepped foot in this section of the country. He did not know what fear was….and was hated by the criminal classes because of his unceasing activity in bringing them to justice.”

Jip, Kidder’s dog continued to mourn for the man who’d adopted him. The Rangers tried to make the dog their mascot but he kept running off, trying to find his master. Finally, Wheeler passed the hat and raised enough money to send Jip to San Jacinto, California where Kidder’s family resided and had been taken there for burial.

The Mexicans tried to smooth things over by firing twenty line riders and firing Police Chief Amador. Wheeler was furious to learn some were soon reinstated. The Ranger captain was able to recover Kidder’s badge and pistol.

There was a slight technicality as to whether Kidder was actually a Ranger when he was killed. His enlistment had expired on April 1st and he was shot on April 3rd. Wheeler was in the field and could not swear Kidder in until he returned. Kidder intended to remain a Ranger and would have to wait until his captain returned to re-enlist. Wheeler, the ex-Army man, claimed there was often an interval between discharge and reenlistment, customarily the soldier’s service was extended until he was actually discharged. In 2006 Jefferson Kidder’s name was placed on the Arizona Peace Officer Memorial at the State Capital in Phoenix, honoring Arizona peace officers killed in the line of duty.