The iconic Western film location is celebrated every year at the internationally famous Lone Pine Film Festival.

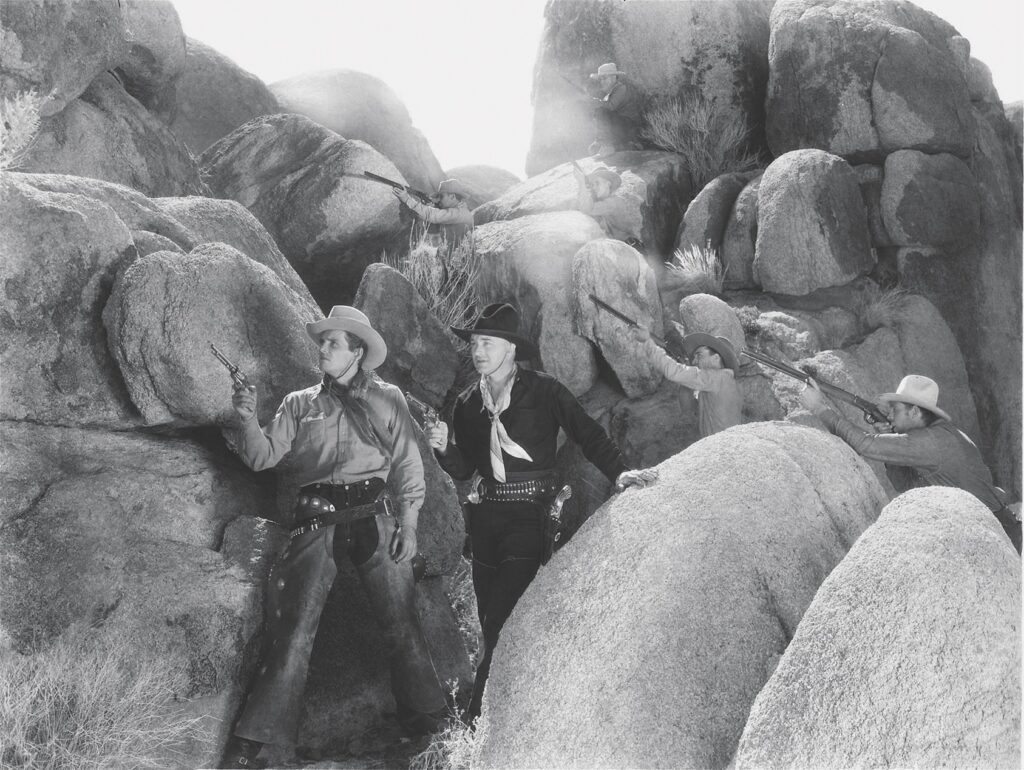

Among the hundreds of long-running film festivals around the world, The Lone Pine Film Festival (lonepinefilmfestival.org), held in early October, is unique: 10 minutes after watching a movie, you can be walking among the spectacular rock formations of the Alabama Hills, spotting the exact locations where it was shot. The area is geographically unique as well. As Gene Autry explained it, “The highest point in the United States is Mount Whitney, and the lowest is Death Valley. It gets to 130 degrees, and you can still see snow at the top of Mount Whitney.” Just over three hours from Los Angeles by car, in the Sierra foothills, the terrain is so striking and varied that a cinematographer could plant his camera, pivot it 90 degrees at a time, and appear to be at four different locations without ever lifting the tripod.

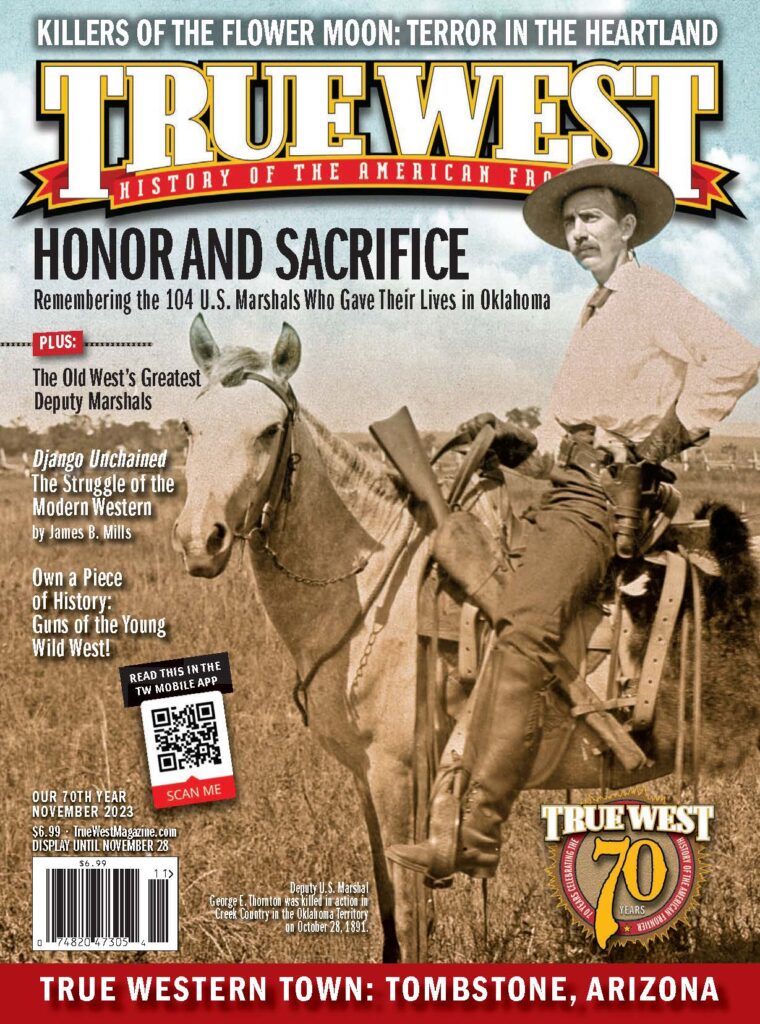

Hollywood moviemakers caught on when, in 1920, Fatty Arbuckle’s The Round-up made spectacular use of the hills, Mount Whitney, the desert and the rough-and-tumble frontier town itself. Soon crews for Will Rogers, Tom Mix and Hoot Gibson were making the trek to Lone Pine.

With the coming of sound came the explosion of B-Western production. In 1935 alone, 16 films were made there, including three John Waynes, two Johnny Mack Browns, two Ken Maynards and the first two Hopalong Cassidys, a series that made Lone Pine their home for 31 movies. Gene Autry would make 18 there, with a dozen for Tim Holt, and a half dozen for Roy Rogers.

Also in 1935, the Alabama Hills would for the first time stand in for frontier India in Lives of a Bengal Lancer, followed by Kim, The Charge of the Light Brigade and Gunga Din!

The rise of color in the 1950s presented it ever more beautifully. In 1953, audiences got a deeper sense of the landscape when Randolph Scott starred in The Stranger Wore a Gun in 3D. Among the 13 films that Scott filmed around the Alabama Hills were four Budd Boetticher/Burt Kennedy collaborations, considered among the best Westerns ever made.

But the public knew nothing of this until the late 1980s, when a Western-loving San Fernando Valley journalist, Dave Holland, was watching a movie featuring Gene Autry sitting on Champion, “by a tall, thick, cucumber-shaped rock which was…at the very same spot where the Indian chase in How the West Was Won began, and where Tim Holt had tried ditching a posse in one of his RKO pictures!”

Historian Marc Wanamaker remembers the day Holland visited him at his Bison Archives. “I have tons of [movie stills] of the Alabama Hills. So we went out there to pinpoint which rock was what.” This evolved into Holland’s book, On Location in Lone Pine, then the tour, and in 1990, The Lone Pine Film Festival, originally based at the local high school, where many of the screenings still take place.

Jim Rogers, an avid Lone Pine fan who owned TV stations in Las Vegas, offered to buy land if the other enthusiasts would build The Lone Pine Film History Museum, which opened its doors in 2006. It holds an astonishing array of props, saddles, vehicles and artifacts, from Col. Tim McCoy’s holsters and hat to the dentist’s wagon from Django Unchained. Just as the film festival has broadened to include a few non-Lone Pine Westerns, the museum has been renamed The Museum of Western Film History (museumofwesternfilmhistory.org).

Among the guests in those early years, who would attend screenings, meet fans and hold panel discussions, were Roy Rogers, Dale Evans, Clayton Moore—The Lone Ranger, Gregory Peck, Ernest Borgnine and Jack Palance. As time has passed, that generation is largely gone. One intriguing program presented this year, Kids of Our Cowboy Kings, will feature the offspring and grandchildren of Joel McCrea, Roy Rogers, John Carradine and Richard Farnsworth.

Greg Parker, who first attended in 1999, will again guide several tours, something he began doing in 2018. Tour-goers are given handouts with screen-grabs from movies to help line up locations. His first location discovery? “At the end of High Sierra, where Humphrey Bogart is chased up Whitney Portal Road. There were six or eight locations right on the road. Since then I’ve found over 2,500 locations from about 180 different movies and television episodes.”

Returning for a second year is Tony Cameron, who last year retraced his father Rod Cameron’s steps on locations for Panhandle. Wyatt McCrea, grandson of Joel McCrea, remembers, “Joel loved Lone Pine and used to go fishing up there quite a bit. He made one film in the Alabama Hills called Cattle Empire. This year will be my 19th or 20th year at Lone Pine. It’s a great way to commemorate some of those great films that were made up there, their contributions to Westerns and film in general, and to keep their spirit alive.”

LAWMEN: BASS REEVES

Between the W.G.A.- and S.A.G.-induced gag orders, and producer Taylor Sheridan’s characteristic reticence, little is known about the miniseries that premieres on Paramount + this fall. But it stars David Oyelowo, and was shot around Fort Worth, Texas. In supporting roles are Dennis Quaid, Donald Sutherland, Barry Pepper and Mo Brings Plenty.

Blu-Ray REVIEW

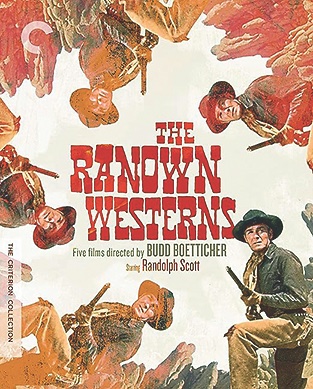

THE RANOWN WESTERNS

(Six-Disc 4K UHD + BLU-RAY COMBO The Criterion Collection, $149.95) Beginning in 1956, a war-hero cavalry officer-turned-screenwriter (Burt Kennedy), a self-confidant bullfighter-turned-director (Budd Boetticher), a savvy producer (Harry Joe Brown), and an actor who personified all of them, Randolph Scott, shot six 18-day second features, four of them against Lone Pine’s Alabama Hills. These dirt-cheap programmers are among the best Westerns ever made. The Tall T, Ride Lonesome, Comanche Station, Decision at Sundown and Buchanan Rides Alone, are minimally populated tense, stripped-down tales of a decent man, usually with a terrible wound in his soul that needs healing. Their noir-ish plots are brutally realistic. The appealing villains are played by a who’s who of masculine actors on the brink of stardom: Richard Boone, Pernell Roberts, Claude Akins and Craig Stevens. And age-creased, gray-haired Scott was never better.