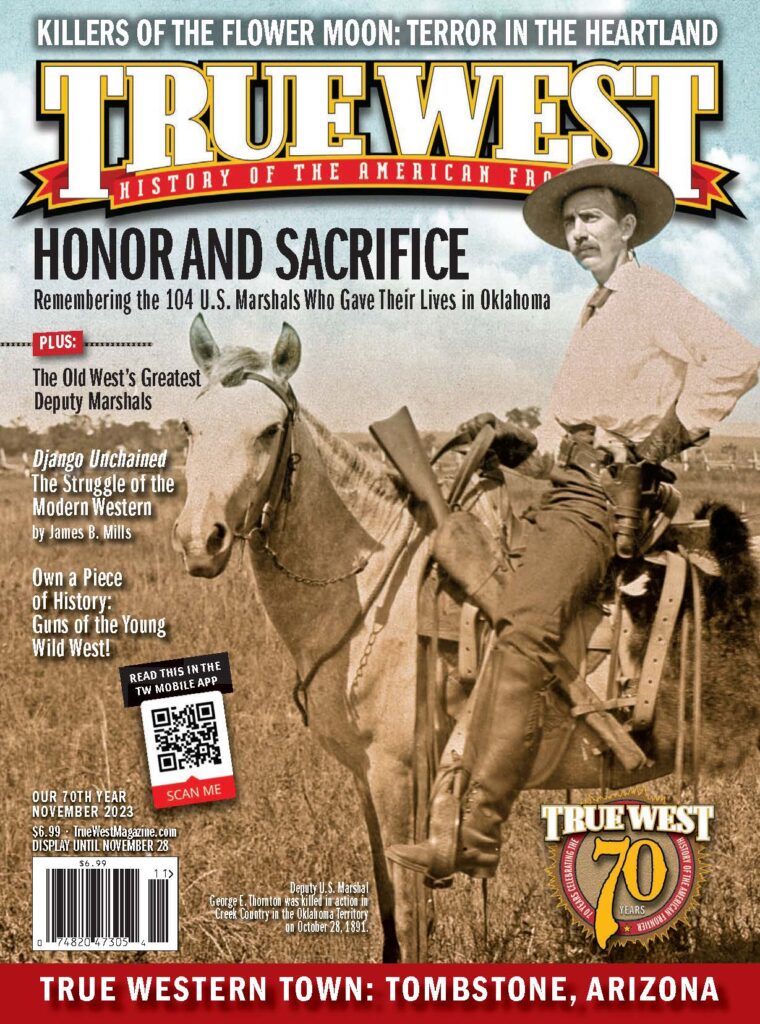

Ten U.S. Marshals and Deputy U.S. Marshals who defined the legendary West

All Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell and All Images Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted

In this list, I’m providing 10 of U.S. Marshals Service personnel who defined the Old West as it was written in books and other media. They are not listed in any order of preference, but if enough television or movies are seen, most of the names are recognizable. They are by no means the only ones who made a lasting impression on our nation’s oldest federal law enforcement organization, just the most prevalent in terms of media.

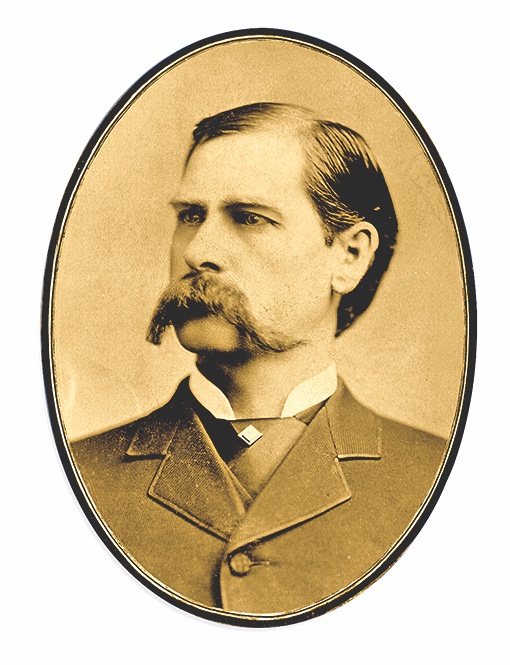

Wyatt Earp

Of the Earp brothers, Virgil was first in our ranks; he was deputy marshal in Tombstone, Arizona, in 1879. Wyatt, like his brother Morgan and friend “Doc” Holiday, was appointed a special deputy U.S. marshal in the Arizona Territory during the fight near the O.K. Corral. He attained a commission in December 1881 after his brother was maimed and unable to continue his position. However, after Morgan was killed in a Tombstone pool hall, Wyatt raised a posse and took vengeance. The lack of proof and accounting discrepancies led to his removal as deputy.

Wyatt wandered into Alaska, Colorado and California after his service. Giving his story to a gentleman named John Flood, he was able to give valuable firsthand accounts of the Tombstone fight and his posse’s pursuit. Eventually, Stuart Lake wrote the comprehensive biography Wyatt Earp-Frontier Marshal, and Hollywood embraced law and order in the West. Long after Wyatt’s death in 1929, Tombstone is practically synonymous with the U.S. Marshals.

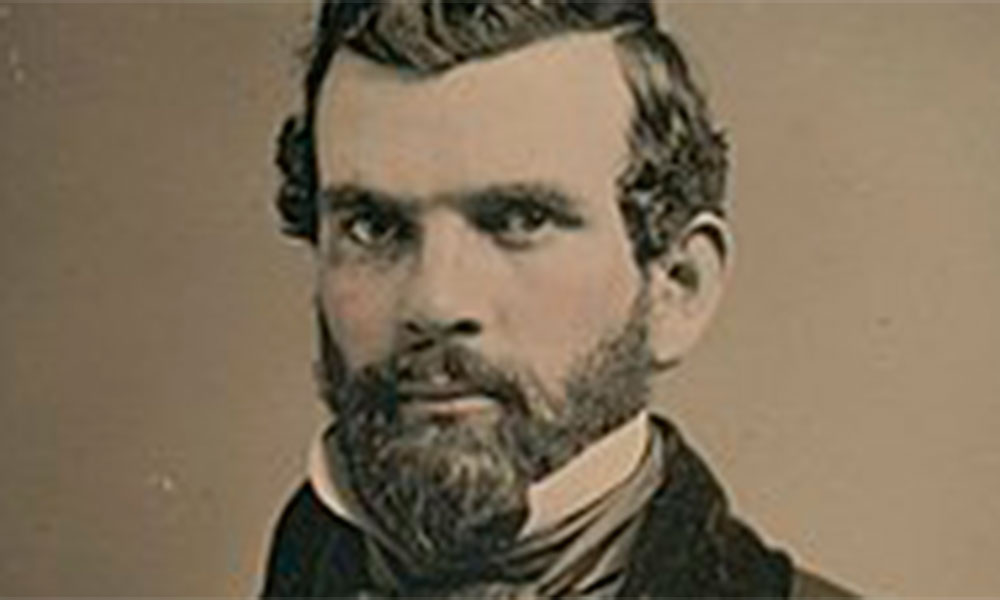

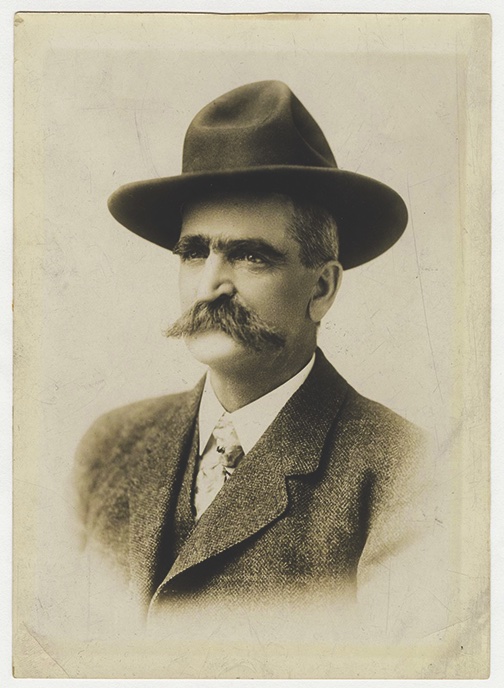

Patrick Garrett

An Alabaman who tried his hand at buffalo hunting in Texas, Garrett found fame in New Mexico Territory. He ran for sheriff of wild Lincoln County and beat the incumbent. Upon his taking the job, he simultaneously became the fourth special deputy U.S. marshal in the process. Why was Garrett in a double position? Simply because U.S. Marshal John Sherman, Jr. (some sources say “John E. Sherman”) had problems finding deputies without an agenda. The last non-lawman he chose was Robert Widenman, who worked a civilian posse with none other than Billy the Kid! He was removed, but a line of Lincoln County sheriffs retained the job.

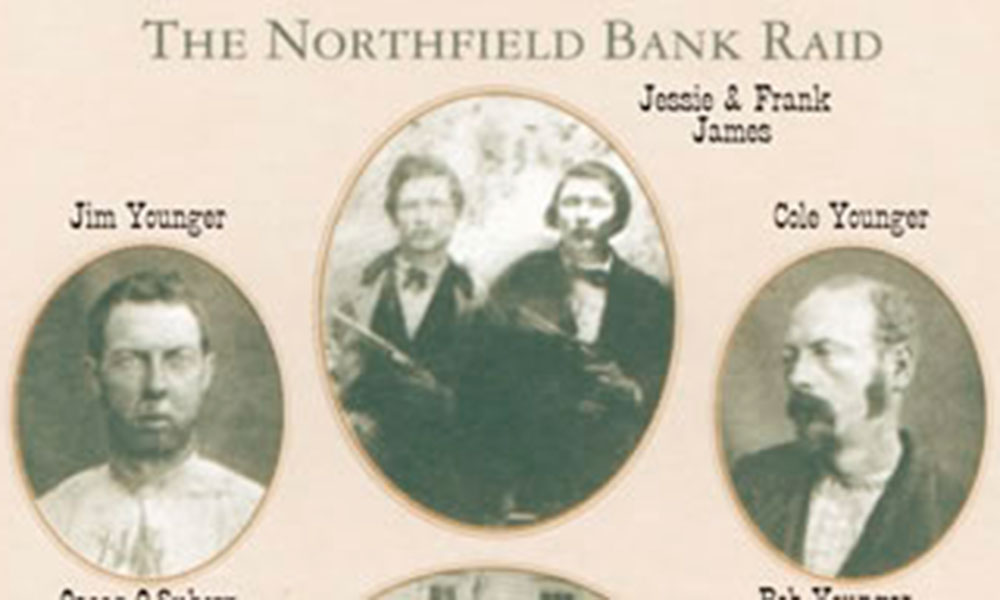

In January 1881, Pat Garrett had just captured Billy the Kid with a group gathered by Azariah Wild, a Secret Service agent. Tragedy struck his office when the Kid escaped from Lincoln, taking the lives of two deputies. Although the legend continues unsettled to this day, the Kid purportedly met his end in a darkened bedroom at Pete Maxwell’s home in Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory. If you ask others, he died in Arizona or Texas. However, regardless of how it ended, the Garrett-Kid rivalry goes down as integral to the legendary Old West.

Bass Reeves

The past quarter of a century, through some great research, this stellar deputy U.S. marshal has been brought into the spotlight. Personally selected by U.S. District Judge Isaac C. “Hanging Judge” Parker in Fort Smith, Arkansas in 1875, Reeves served in several districts for 32 years. What is more amazing is that Reeves, an African American, was born a slave in Texas and overcame mountains of adversity to escape and fluently speak the Chickasaw language. Additionally, he moved with ease among the many tribes in what is currently Oklahoma. Sometimes in disguise, Reeves captured scores of fugitives—and even turned in his own son.

Hollywood giants Morgan Freeman and Will Smith took interest in bringing Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves to a wider audience. Several films and series focused on him or were based on aspects of his career. Fort Smith boasts the only equestrian statue in Arkansas, forged by sculptor Harold Holden, of Deputy Reeves. It was dedicated in 2012.

Seth Bullock

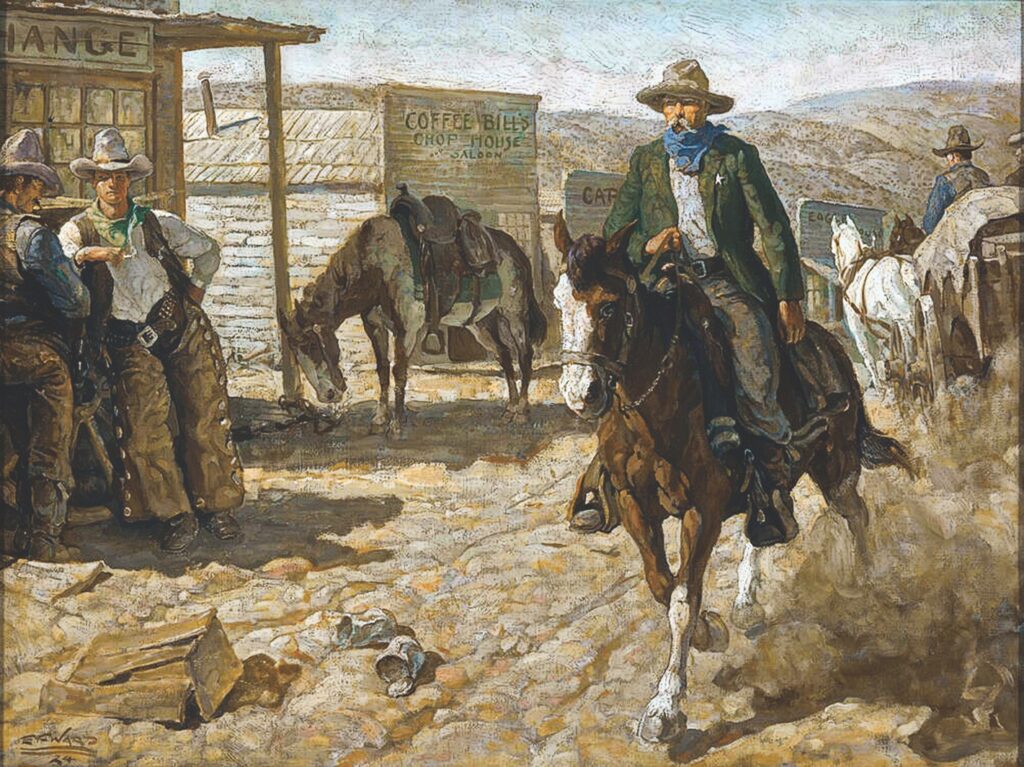

Anyone who saw HBO’s Deadwood watched this lawman protagonist. He arrived in Deadwood shortly after the death of James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. However, after he was appointed a deputy U.S. marshal, Bullock made an impression with his savvy in the rough-and-tumble town. A personal friend of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, he attained the rank of U.S. marshal.

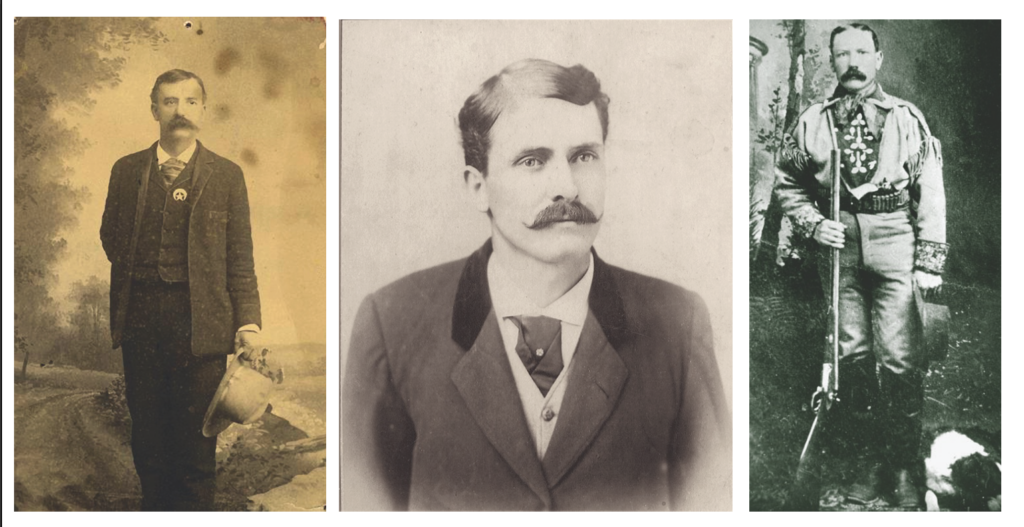

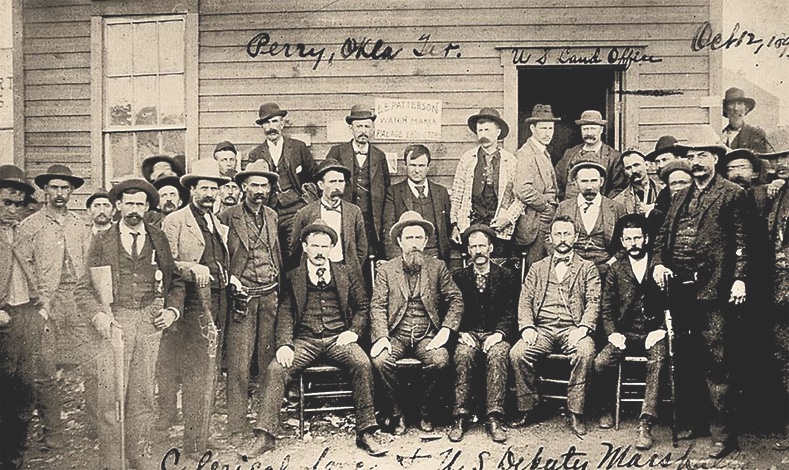

Heck Thomas,, Bill Tilghman and Chris Madsen

Collectively, they were called the “Three Guardsmen of Oklahoma,” which is why they are treated as one entry. The hazardous duty of the Indian and Oklahoma Territories (yes, they were once different jurisdictions) saw these three through the toughest of times and places in the 1890s and beyond. Only one became an appointed U.S. marshal (Tilghman remained a deputy marshal), while the third became synonymous with tough gunfights (Deputy Marshal Thomas). All three were known for a running war with the Doolin Gang. Their combined successes cleaned out the outlaws by 1897. Oklahoma became a state a decade later.

In 1986, when a statue was cast for a memorial titled Frontier Marshal to grace the entrance to our agency’s headquarters, sculptor Dave Manuel used three images to make this iconic image: Wyatt Earp, Bill Tilghman and Heck Thomas. Visitors to U.S. Marshals Service headquarters often take photographs next to the statue.

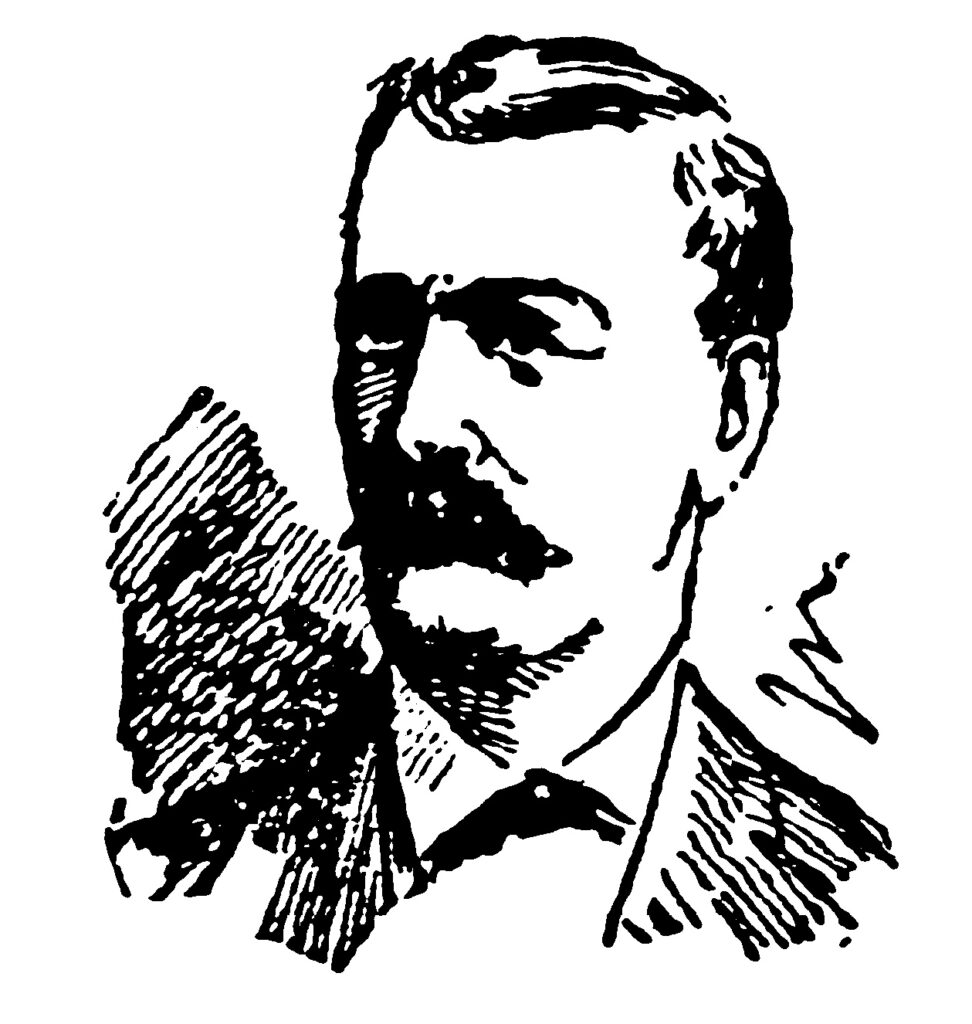

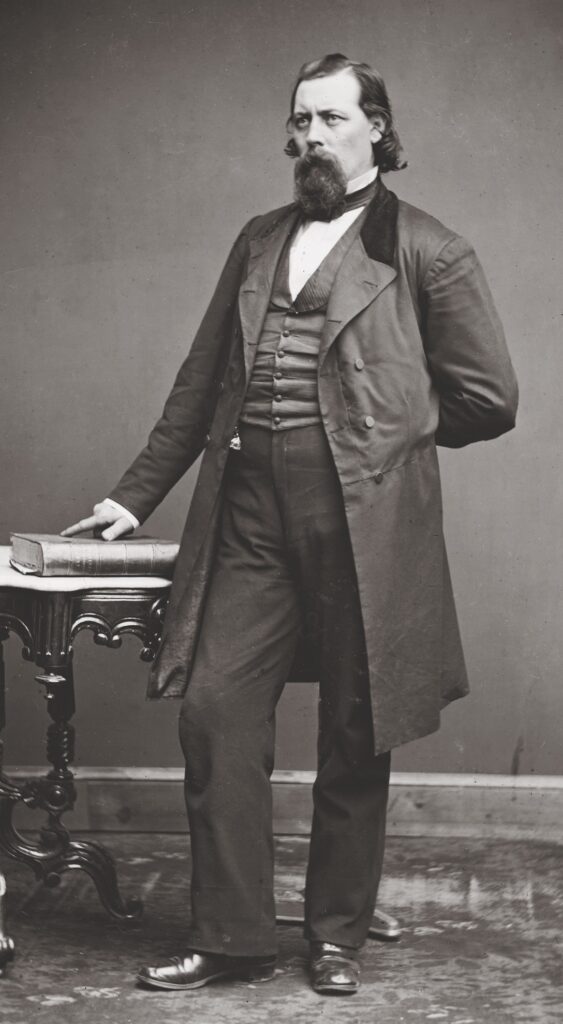

Crawley P. Dake

The unfortunate Dake was the appointed U.S. marshal during the Tombstone era. The difficult late 1870s and early 1880s saw mail robberies, tribal uprisings and the famous O.K. Corral fight (which was not actually in the corral) against a group of rustlers known as “the Cowboys.” This group stretched into the cattle trade moving to and from Mexico. U.S. Marshal Dake appointed excellent deputies, although two, John H. Adams and Cornelius Finley, fell victim to his adversaries. He took enormous risks, both physically and monetarily, to bring law and order to the Arizona Territory. By appointing Virgil Earp as a deputy marshal in Tombstone in late 1879, U.S. Marshal Dake had an able assistant. However, after the O.K. Corral gunfight in October 1881, Virgil was wounded and unable to continue his duties. His brother Wyatt took his place, but bad bookkeeping cost his U.S. marshal his job. In the late summer of 1882, despite Dake’s phenomenal efforts, he was removed and died penniless.

The “man behind the Earps” deserved the credit for facing down the “Cowboy” juggernaut—some say the organization numbered almost 400 people. It was U.S. Marshal Dake who had the unenviable job of breaking their hold on the territory with any deputy available. He became better known due to the Tombstone fight.

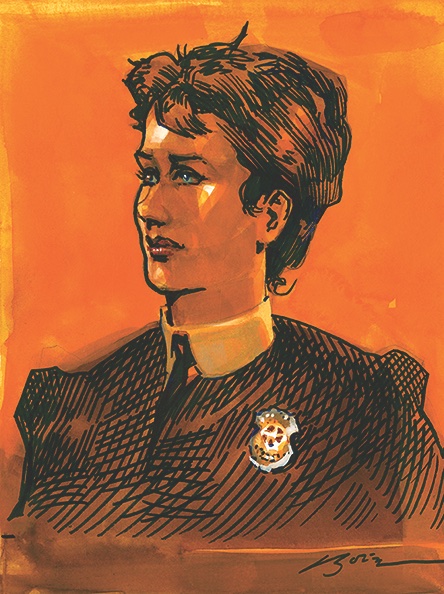

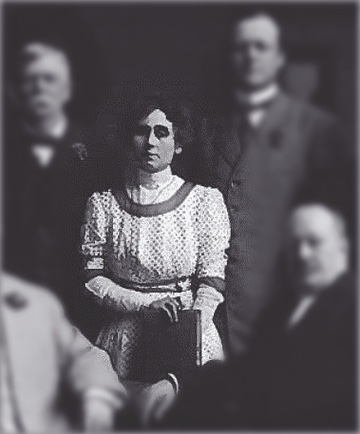

Ada Curnutt (Carnutt)

Although she was not the first female deputy U.S. marshal, Curnett was among the first wave hired. Working as an office deputy in the Indian Territory in March 1893, Curnutt famously answered the call to arrest two fugitives in an Oklahoma City saloon. With no deputy to assist her, she started to deputize townsmen to bring them to the paddy wagon. They surrendered. Although largely unknown before or after this event, she represented the beginning of a rising level of participation of female deputies in the modern day.

David Neagle

Deputy U.S. Marshal David Neagle was shoved into the spotlight in August 1889. While accompanying Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field in Lathrop, California, a man named David Terry attacked his protectee. Deputy Neagle shot and killed Terry, who was sporting a knife. Despite announcing his position, local law enforcement arrested him. This set off a long chain of legal actions that were resolved in a Supreme Court case in April 1890, In re Neagle. The long fight was worth it—as it further defined powers of the U.S. Marshals when in conflict with state and local jurisdictions. Deputy Neagle is more apt to be known to legal scholars, but his actions defined broader limits of federal power—and ultimately determined how overlapping jurisdictions resolved themselves.

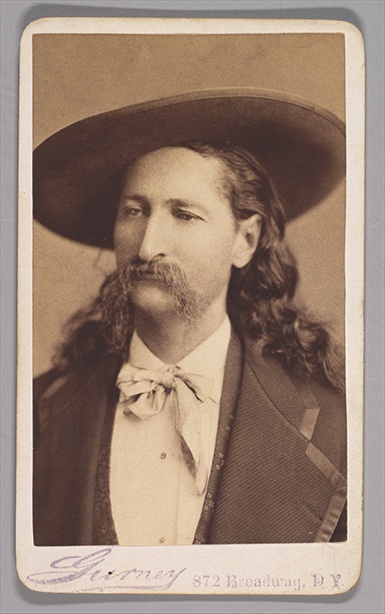

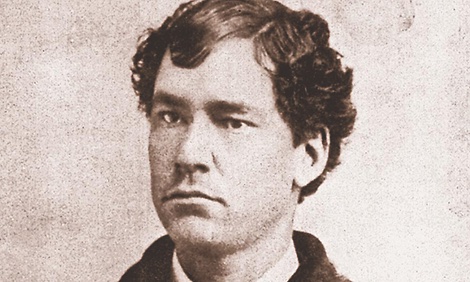

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok

Part trail scout, part lawman, James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok defined a confusing mix of abandon and law enforcement. Long before his tragic death during a card game in Deadwood, South Dakota, in 1876, Hickok served as a deputy U.S. marshal in Fort Hays, Kansas. The term of his service was unclear, likely two years or so, but the long shadow of Hickok in his many exploits followed him through the history books. Calamity Jane notwithstanding, Wild Bill served for a time with us.

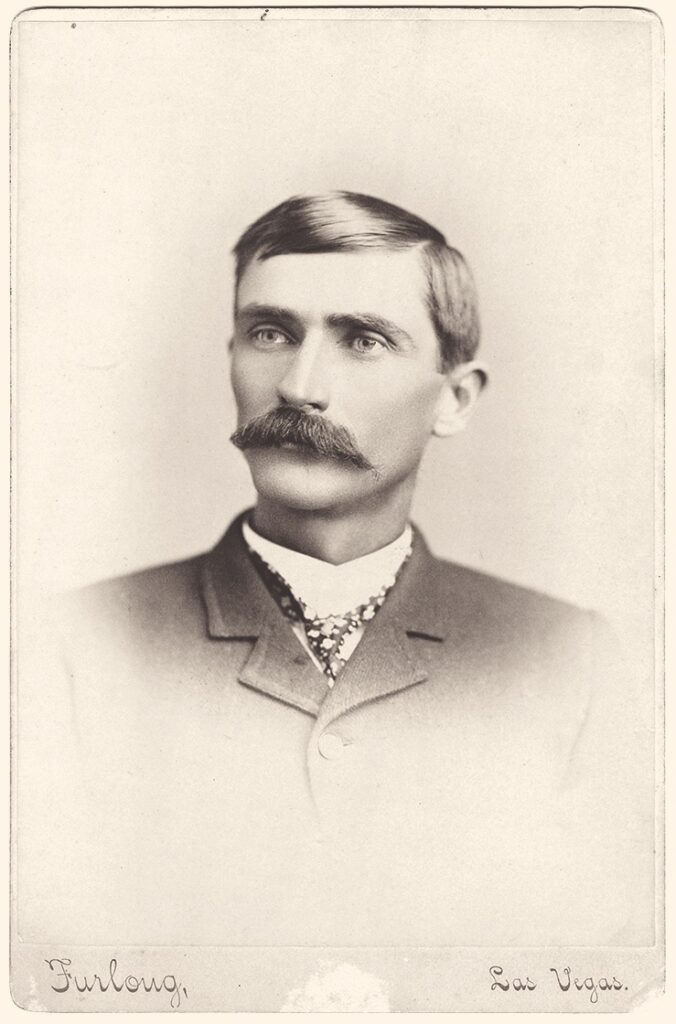

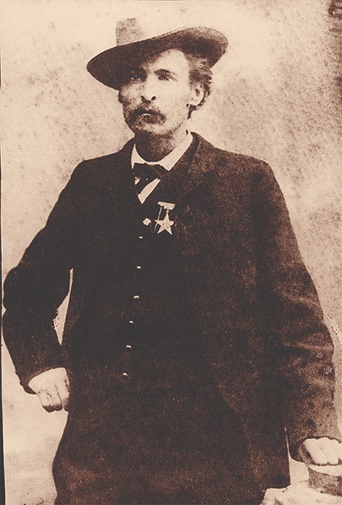

Jim Courtright

Most equate this lawman-outlaw on the other side of the badge, but for a time, Jim Courtright was a deputy U.S. marshal serving in Fort Worth, Texas. His image was not unlike Gen. George A. Custer or Wild Bill Hickok. His short stint as a lawman saw a famous gun battle in Texas. Finding himself on the wrong side of a shoot-out in 1878, Courtright met his end on the street.

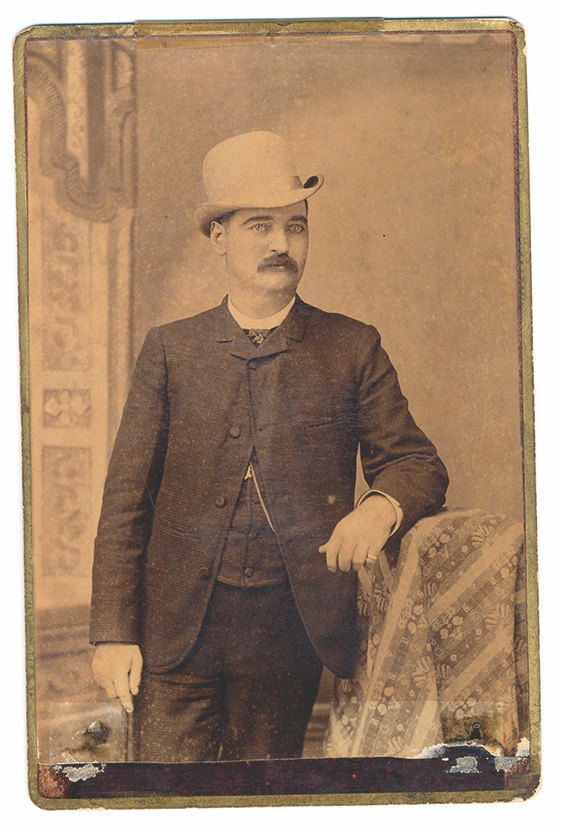

Special Mention—William “Bat” Masterson

Masterson was known for his exploits in the Old West, but as city marshal in Dodge City and elsewhere. He was often mistaken as a federal officer, but he was not actually a deputy U.S. marshal until 1905 in the Southern District of New York. His brother Jim was indeed in our service during the Ingalls fight against the Dalton Gang in the Indian Territory. Bat went on to become a famous sportswriter. Still, his trademark bowler hat, a sign of prestige, is media wildfire.

Ten U.S. Marshals or Deputy U.S. Marshals You Should Know About (1789-1930)

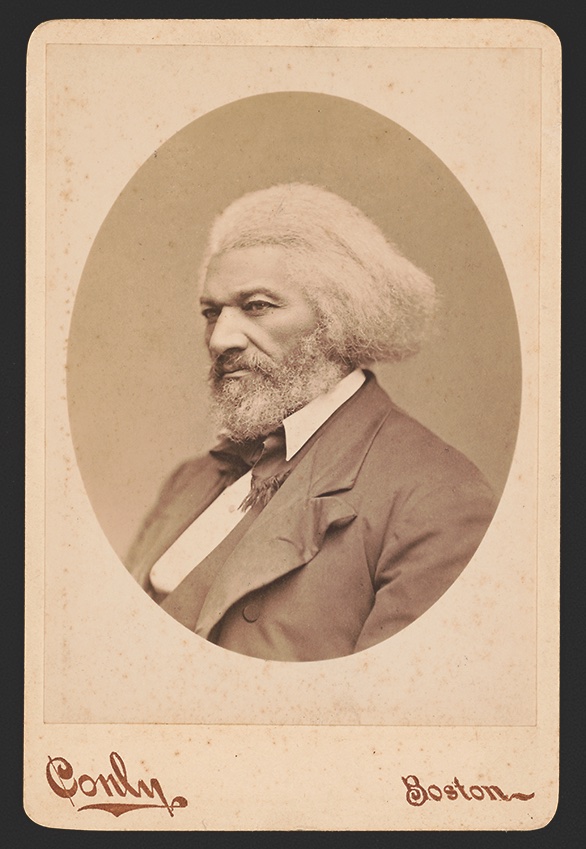

Frederick Douglass

More known as an orator and statesman, Douglass was the first Black U.S. Marshal in 1877. Although he was back east, in the District of Columbia, U.S. Marshal Douglass broke barriers in wearing the star. He proved a popular leader, reorganizing the D.C. jail and even earning the respect of the family that formerly enslaved him. He served a full term before moving on to other public offices.

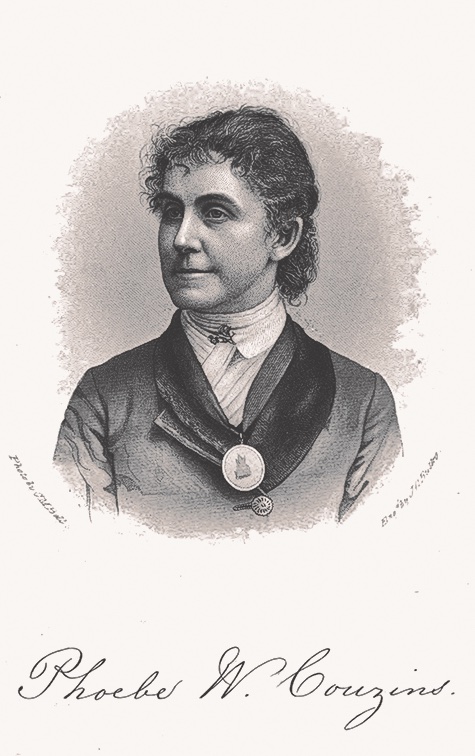

Phoebe Couzins

She was not only the first-known deputy U.S. marshal, but the first female U.S. marshal as well. A contemporary of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Couzins held progressive views in the suffrage movement of the time. Nonetheless, she worked as a deputy for her father, U.S. Marshal John E.D. Couzins of the Eastern District of Missouri, for several years beginning in 1884. Three years later, at the sudden passing of her father in office, Phoebe was appointed on an interim basis. She left the U.S. marshal’s office shortly after the formal appointment of her successor, but reportedly was buried with her badge when she passed in 1913.

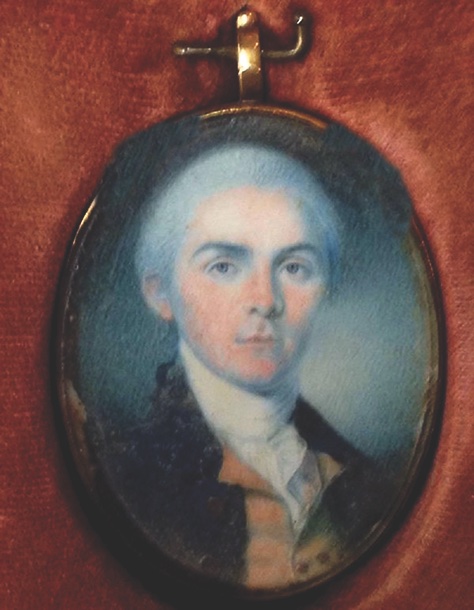

Robert Forsyth

Born in Scotland, Forsyth served in the Continental army during the American Revolution. He later moved to Augusta, Georgia, where he was one of the first 13 U.S. marshals appointed by President George Washington on September 26, 1789. His term as U.S. marshal for the district of Georgia was cut short when he was shot while attempting an arrest in January 1794. His death was the first of those personnel who died in the line of duty. His son John later served as governor and Secretary of State.

Elfego Baca

One of New Mexico Territory’s most notable lawmen, Baca was first Socorro County deputy sheriff, then later a deputy U.S. marshal. From 1888 to 1890, his federal service struck fear into his opposition. Moving beyond the badge into legal practice and politics, he served Socorro County in several public offices.

Ward Hill Lamon

As U.S. marshal of the District of Columbia from 1861 to 1865, Lamon was probably better known as the friend and protector of President Abraham Lincoln. In February 1861, Lamon quietly slipped President-elect Lincoln into Washington, D.C. to prepare for inaugural ceremonies. He became U.S. marshal two months later. Likewise, he accompanied President Lincoln as a de facto bodyguard for the Gettysburg Address and even under fire at Fort Stevens. Sadly, in April 1865, U.S. Marshal Lamon was sent to restore order in newly occupied Richmond, when his friend was assassinated at Ford’s Theatre.

Grant Johnson

While many know of the legendary career of longtime Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves, he was only one of several well-regarded Black deputy U.S. marshals. Reeves often partnered with Deputy U.S. Marshal Johnson, who, like him, was born a slave. His parents, partly of Creek origin, were freed and allowed important opportunities for their son. He worked as a deputy in Western Arkansas and Northern Indian Territory from 1888 to 1906. His goals were often achieved without drawing his gun, and his first fatality was 15 years into his career.

Charles F. Colcord

Kentucky-born Colcord was an Old West “Renaissance Man.” After a youth largely spent on ranches, he developed as a businessman, and after the Land Rush of 1889, a deputy U.S. marshal. Additionally, he worked alongside Bill Tilghman pursuing members of the Dalton Gang. His footprint in Oklahoma City was widespread, reaching from their first police force to real estate development.

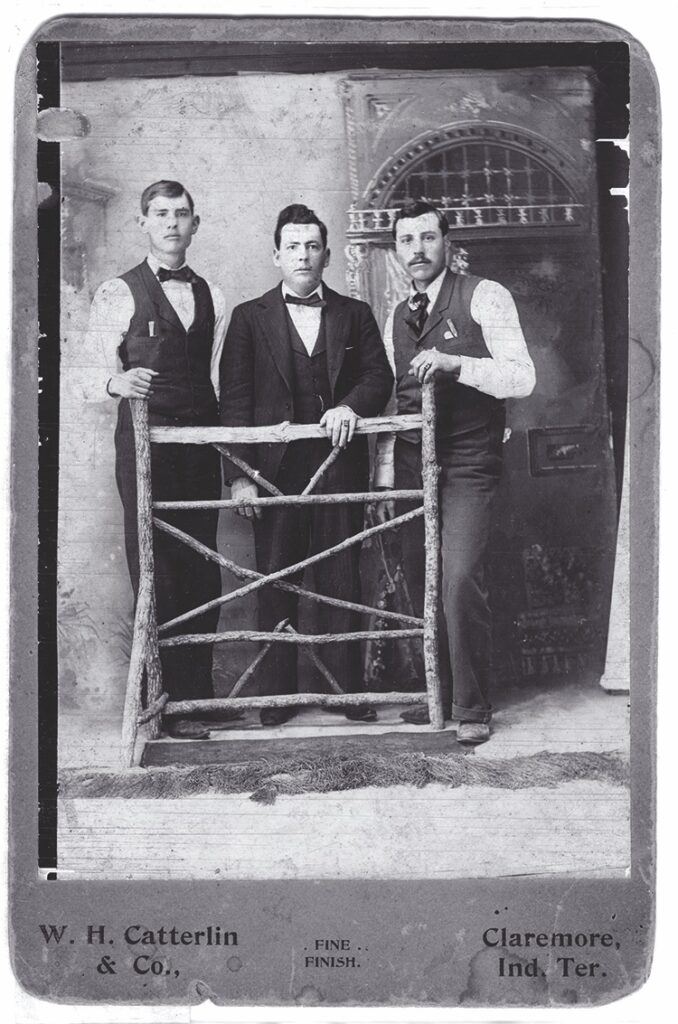

Ed Reed

One of the most interesting contrasts in history was that the famous female outlaw Belle Starr had a son who was a lawman. He was not even 20 years old when his mother was killed in an ambush (some suspected he was the culprit). Although he was engaged in petty crimes early in life, after a stint as a railroad guard he became a deputy U.S. marshal in 1895. Efficient during his short career, he met his end like his mother had, in an ambush at a store in Claremore, Oklahoma.

Jenette “Jenny” Norrish

In an age when female deputies increased markedly, Deputy U.S. Marshal Norrish was the first-known acting chief deputy for the Southern District of Ohio in June 1919. By then, she had several decades on the job and became known across the country. The March 10, 1912, issue of the Buffalo Courier Express announced that Deputy Norrish “could name the big crooks of the country for the last dozen years, and, furthermore, she would know them should she meet them face to face.”

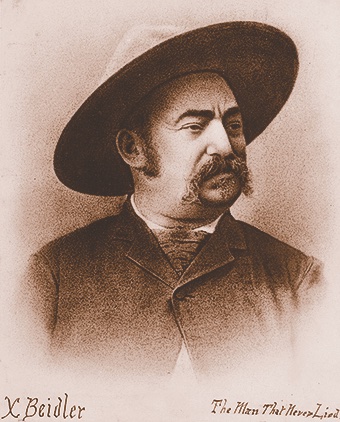

John X. Beidler

More famous for his career as a pioneer and vigilante leader in Montana Territory, Beidler naturally progressed into a federal lawman in the mid-1870s. Until his health failed, he remained a deputy U.S. marshal for the next decade. By then, admirers financially supported him and later, after his death, memorialized him.

U.S. Marshals Roll Call of Honor

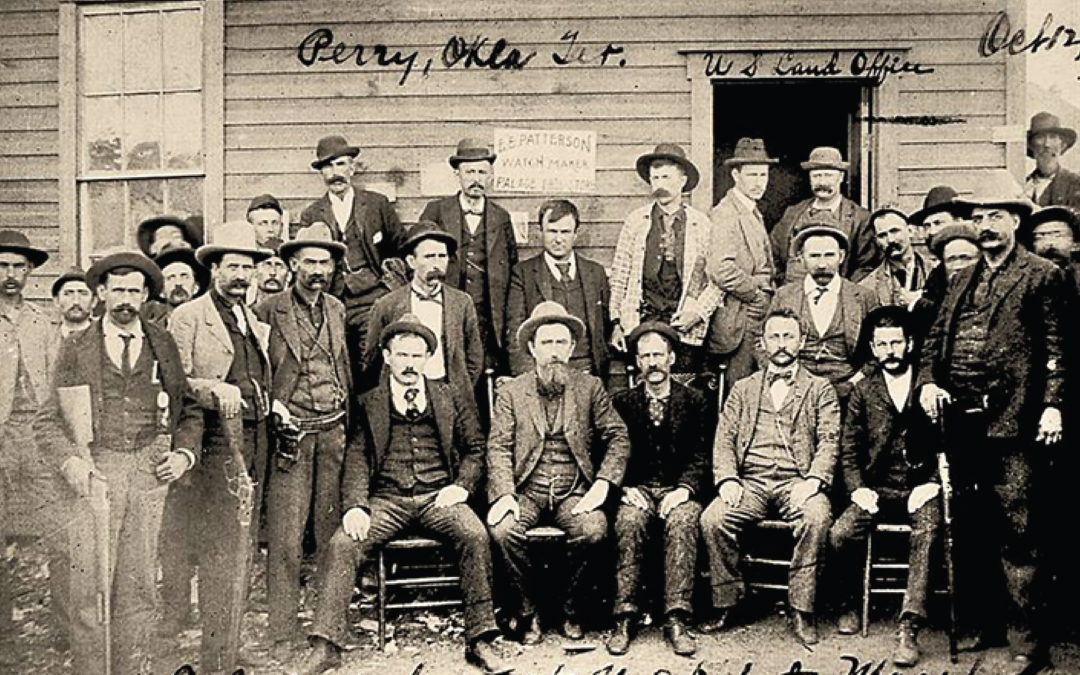

Oklahoma, Indian Territory, and Related Western District of Arkansas

Until 1889, all of present-day Oklahoma was part of the Western District of Arkansas. That year, Indian Territory was created as one district, and in 1895 divided into three additional jurisdic-tions (Northern, Central and Southern Districts). In 1902, Indian Territory, Western District was formed. In 1890, Oklahoma Territory was formed from northern sections (and a strip of modern-day Kansas). With Oklahoma’s statehood, the Eastern and Western Districts became effective in 1907. From February 16, 1872 to May 23, 1935, 104 men were killed in the line of duty in Oklahoma with the U.S. Marshals Service, nearly one-third of the men and women who have died while serving as a marshal.

John Zeke • February 16, 1872 • W/AR

W.T. Bentz • February 22, 1872 • W/AR

Black Sut Beck • April 15, 1872 • W/AR

Sam Beck • April 15, 1872 • W/AR

William Hicks • April 15, 1872 • W/AR

George Selvidge • April 15, 1872 • W/AR

Jim Ward • April 15, 1872 • W/AR

Riley Woods • April 15, 1872 • W/AR

William Beck • April 16, 1872 • W/AR

Jacob G. Owens • April 16, 1872 • W/AR

April 15, 1872, was known as the deadliest day in the history of the U.S. Marshals in the Old West. The Goingsnake Massacre was the culmination of a jurisdictional conflict involving U.S. District Court in the Western District of Arkansas and the Cherokee Nation.

Two months prior, Ezekiel “Zeke” Proctor, a prominent citizen in the Nation, argued with American James Kesterson and accidentally shot his wife, Polly. There was confusion as to jurisdiction, although the laws of the Cherokee conferred adoptive citizenship on Kesterson. He filed a claim with the U.S. District Court in Fort Smith nonetheless, and a warrant was handed to Deputy U.S. Marshals Jacob G. Owens and Joseph Peavey. Their posse, which numbered about 15 people, rode to the Whitmire Schoolhouse in Christie, Indian Territory, where Proctor was being tried. Accounts vary, but the deputies came under fire with little cover. Six of the posse members perished that day, and two more, including Deputy Owens, died the next day. After President Ulysses Grant intervened, charges against Proctor were dropped. In a strange twist of irony, Proctor later became a deputy U.S. marshal himself.

Marcus L. Parker • March 22, 1873 • W/AR (killed in KS)

Perry Duval • November 2, 1873 • W/AR

William Spivey • August 6, 1874 • W/AR

Willard Ayers • August 11, 1880 • W/AR

Thomas Young • August 25, 1882 • W/AR

Dave H. Layman • April 10, 1883 • W/AR

John McWeir • July 2, 1883 • W/AR

In September 1882, a couple driving a wagon near Shawnee, Indian Territory, was ambushed. The man on the wagon was killed, and the assailant was identified by his companion as young Johnson Foster. After members of the Seminole Lighthorse captured Foster, Deputies McWeir and Wilkinson, along with a cook/guard, were sent to Fort Reno to bring the prisoner back to Fort Smith. On the return trip, Wilkinson and the cook left the prisoner with McWeir while they sought supplies. Upon their return, they found Foster gone and McWeir dead. The prisoner was later killed by citizens of the Creek Nation.

Addison Beck • September 27, 1883 • W/AR

Lewis Merritt • September 27, 1883 • W/AR

William Leech • April 10, 1884 • W/AR

Bud Pusley • November 9, 1884 • W/AR

Jim Guy • May 1, 1885 • W/AR

Bill Kirksey • May 1, 1885 • W/AR

J.E. Richardson • March 29, 1886 • W/AR

Henry Miller • April 9, 1886 • W/AR

William Irwin • April 13, 1886 • W/AR

Sam Sixkiller • December 24, 1886 • W/AR

William Kelly • January 17, 1887 • W/AR

Mark Kuykendall • January 17, 1887 • W/AR

Henry Smith • January 17, 1887 • W/AR

William Fields • April 10, 1887 • W/AR

Dan Maples • May 4, 1887 • W/AR

Frank Dalton • November 27, 1887 • W/AR

Deputy U.S. Marshals Dalton and Cole were sent across the river from Fort Smith to arrest David “Baldy” Smith, wanted for murder and encamped nearby. As Dalton walked to Smith’s tent, his quarry emerged and shot him. Although several of Deputy Dalton’s brothers also served as deputy marshals after their brother’s death, it was late or missing pay that turned them to a life of crime to bring in cash.

E.A. Stokley • December 3, 1887 • W/AR

John Trammel • June 26, 1888 • W/AR

John Phillips • June 30, 1888 • W/AR

William Whitson • June 30, 1888 • W/AR

Mose McIntosh • November 9, 1888 • W/AR

Z.W. Moody • March 15, 1889 • W/AR

Jim Williams • June 5, 1889 • W/AR

Robert Cox • April 14, 1890 • IT

Jim Billy • July 13, 1890 • EDTX (killed in later Indian Territory jurisdiction)

David Sigemore • July 31, 1890 • W/AR

Marion Prickett • December 15, 1890 • W/AR

Steve Pensoneau • February 6, 1891 • OT

Bernard Connelley • August 19, 1891 • W/AR

Ed Short • August 23, 1891 • OT

Deputy U.S. Marshal Ed Short was one of the many lawmen told to be on the lookout for the Dalton Gang, who had recently held up a train. As gang member Charley Bryant sought medical attention, the deputy recognized him. He arrested the outlaw and arranged for travel to take him to prison facilities. While en route, Deputy Short gave a railway clerk one of his two pistols and momentarily left the clerk in charge of the prisoner. Unfortunately, the clerk literally put away the gun and ignored Bryant, who grabbed the gun and followed the deputy onto a platform. He shot Short there, but not before the lawman returned fire. Both died.

Joseph S. Wilson • September 23, 1891 • IT

R.L. Taylor • October 1, 1891 • OT

George Thornton • October 28, 1891 • OT

Josiah Poorboy • December 8, 1891 • W/AR

Thomas Whitehead • December 8, 1891 • W/AR

John B. Pemberton • February 20, 1892 • W/AR

John Fields • October 12, 1892 • W/AR

Tom C. Smith • November 4, 1892 • EDTX (killed in later Indian Territory jurisdiction)

Floyd Wilson • December 13, 1892 • W/AR

Sherman Russell • July 12, 1893 • W/AR

Joe Gaines • August 22, 1893 • EDTX (killed in later Indian Territory jurisdiction)

Richard Speed • September 1, 1893 • OT

Thomas J. Hueston • September 2, 1893 •

Lafayette Shadley • September 3, 1893 • OT

Bill Harrison • May 9, 1894 • OT

Thomas L. Martin • June 4, 1894 • W/AR

Abner D. McLellan • July 20, 1894 • IT

M.W. Joe Nix • August 3, 1894 • IT

Lincoln Keeney • November 24, 1894 • IT

Newton LeForce • December 5, 1894 • IT

John Beard • December 9, 1894 • W/AR

Jim Nakedhead • February 27, 1895 • W/AR

W.C. McDaniels • March 16, 1895 • W/AR

Lawrence Keating • July 26, 1895 • W/AR

John Garrett • July 30, 1895 • N/IT

John Davis • August 1, 1895 • W/AR

Edward Thurlo • February 10, 1896 • S/IT

Thomas R. Madden • April 19, 1896 • W/AR

A.W. Johnson • October 21, 1896 • S/IT

Bill Arnold • March 17, 1898 • N/IT

J. Boley Grady • July 17, 1898 • C/IT

L.S. Hill • July 17, 1898 • C/IT

Joseph Heinrichs • March 15, 1899 • N/IT

Hickman Bruner • June 22, 1899 • N/IT

Henry Peckenpaugh • November 27, 1899 • C/IT

Deputy U.S. Marshal Peckenpaugh met his end when bravely coming to the aid of Wilburton, Indian Territory, Postmaster W.A. Cox, who was being robbed by two men in slickers. The two thieves, who had relieved Cox of his daily receipts, ran into the path of Peckenpaugh and a companion. He grabbed one of the men by the slicker but lost his grip. Both drew their weapons, but the deputy’s opponent was able to fire first. The two suspects ran but were later captured. Peckenpaugh left a widow and five children.

Herbert M. Goddard • August 14, 1900 • C/IT

Tom Taylor • October 13, 1900 • OT

John Poe • September 25, 1901 • S/IT

Lute Houston • October 20, 1902 • OT

John B. Jones • July 3, 1903 • OT

Edward D. Fink • November 28, 1904 • W/IT

J. Henry Vier • February 20, 1905 • N/IT

Deputy U.S. Marshal John Henry Vier and a posse went to a double log house near Oaks, Indian Territory—the home of a Cherokee citizen—on a charge of larceny. Deputy Vier dismounted, stood at the door, and turned to instruct the group with him. As he did, someone inside the home shot him. Several of the posse members, including Vier, were able to return fire until they ran out of ammunition. It was believed that the owner was not the assailant, but John and his brother, Charley Wickliffe, who was also wanted on outstanding warrants. Deputy Vier died shortly after the gunfight.

Ike L. Gilstrap • March 12, 1906 • N/OK

James Bourland • May 24, 1906 • OT

James H. Bush • June 27, 1906 • W/AR (No OK Territorial ties)

Sam Roberts • July 5, 1907 • C/IT

John Morrison • July 17, 1907 • W/IT

L.P. Dixon • July 19, 1907 • W/IT

George Williams • November 16, 1907 • N/IT

A.W. Holden • May 7, 1909 • E/OK

Holmes Davidson • July 23, 1914 • E/OK

Deputy U.S. Marshal Holmes Davidson was well-known in the region from Muskogee to Tulsa, Oklahoma. At 52 years old, the Missouri native was a widower with a grown son who was also a deputy marshal. He had already “cleaned up” the town of Sapulpa from various alcohol violations. With Deputy U.S. Marshal William “Ed” Plank and a revenue agent, Davidson searched the Tulsa County home of William Baber for contraband liquor. The two deputies were fatally shot at point-blank range by the owner, who turned himself in.

William E. Plank • July 23, 1914 • E/OK

Robert Logan • March 9, 1915 • E/OK

George W. Adair • September 11, 1921 • E/OK

J. Walter Casey • July 16, 1923 • W/OK

Robert Sumter • August 9, 1933 • E/OK

Charles T. Warner • May 23, 1935 • N/OK

Reference Index

IT: Indian Territory

EDTX: Eastern District of Texas

OT: Oklahoma Territory

W/AR: Western District of Arkansas

E/OK: Eastern District of Oklahoma

N/OK: Northern District of Oklahoma

W/OK: Western District of Oklahoma

N/IT: Northern Indian Territory

S/IT: Southern Indian Territory

C/IT: Central Indian Territory

W/IT: Western Indian Territory

The U.S. Marshals Museum

Decades in the planning, the grand center opened Independence Day weekend.

The grand opening of the U.S. Marshals Museum was on July 1, 2023. Built on a bluff above the Arkansas River just a mile from Fort Smith National Historic Site in historic downtown Fort Smith, Arkansas, the museum is open seven days a week for visitors to rediscover America through the history of the nation’s oldest federal law enforcement agency. Explore the five exhibit galleries and learn how the U.S. Marshals Service has evolved from colonial and frontier days to the present day. All ages will enjoy educational programming through the museum’s National Learning Center. And before leaving, take time to tour the Samuel M. Sicard Hall of Honor, which honors more than 350 marshals killed in the line of duty since 1789.