Growing up in the Texas Pan-handle, I often visited a cousin who worked at the 6666 Ranch, one of the old historic outfits in Texas, so I am quite familiar with the cowboy lifestyle. Though I’ve never been drawn to doing the actual work of a cowboy, I do connect with some of the essentials they hold dear: raw land, solitude, self-reliance, trusting those you work with, earning respect and being your own boss. Many of them might laugh at my comparison between common threads we share, since their work is so much more physical, dangerous, and less rewarding financially, but I think some of the ranching men and women I’ve gotten to know over the years would understand.

I have been drawn to photograph cowboys for 25 years—in tintype for the past six years. The tintype process takes me even closer to the cowboys in important ways, I believe. It requires more patience, and making each plate by hand has shown me that I’m not always in control—environment, weather and chance always play a part in the final product. In this world of yesterday deadlines and “perfect digital photography,” I find a renewed awareness that patience and serendipity are important gifts. I would like to thank all those who gave me time and tolerance, allowing me to photograph them in this arcane style of photography that slowed us all down so we could get to know each other a bit better.

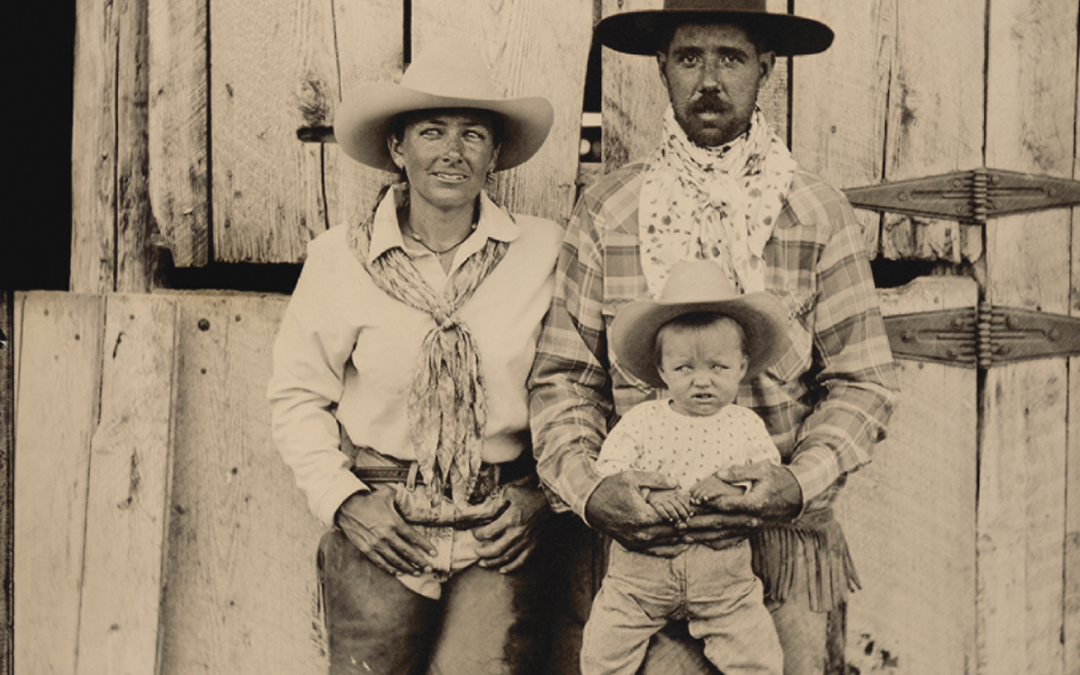

People who have seen my cowboy photos often ask if I have “styled” the cowboys. Did I tie their scarves just so? Did I ask them to put the leather brush cuffs on their arms? Did I turn up their shirt collars like that? The answer to all these questions is a clear “no.” I did not have to do anything to their clothes or their look. I photographed the men and women exactly as I found them. These are their ordinary, workaday outfits—not costumes, not dress up. Every piece and feature serves a purpose in their jobs. It’s amazing and refreshing that in the early 21st century there are still people who get to go to work dressed like this.

In Minden, Nebraska, I met Tom Kelly and his two daughters on their small family ranch—one of the increasingly few family ranches left in the West. I made my first mistake with Tom by inadvertently running my trailer tires about a foot off the driveway onto his grass. Tom was visibly upset, but he gently informed me that he considered grass absolutely precious. It was hard to grow and keep in the dry plains of Nebraska and it was the thing that kept his ranch going, the thing that fed his cattle, from which the family earned their living. I felt terrible, but Tom quickly forgave me and made me feel very welcome at his home. When it was time to leave the Kellys, Tom, who’s raised his daughters to be excellent horsewomen and ranchers, pulled me aside and said, “Robb, please promise me one thing. That you’ll get it right.” I knew exactly what he meant. His way of life is misunderstood in many ways. Cowboys are sometimes thought of as a brutish, drinking lot with little respect for the environment. The truth as I saw it was that these are kind, family-centered people with great respect for nature, animals, and God’s gifts and for a hard day’s work. I’m sure Tom will let me know if I succeeded or not.

Excerpt and tintype photographs from Still: Cowboys at the Start of the Twenty-First Century by Robb Kendrick and Marianne Wiggins published by the University of Texas Press. The book is available at bookstores everywhere and directly from the press at 800-252-3206.

Robb Kendrick is a sixth-generation Texan who contributes regularly to National Geographic and focuses his efforts on in-depth projects that use historic photographic techniques such as the tintype process. He currently resides in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

Faithe, with her husband Merlin Rupp, a lifelong range worker from Burns, Oregon, who retired a few years ago after a horse fell under him and broke his neck, knocking him out for three weeks

Martin Anseth, with Jiggs and Patches, at EZ Ranch in St. Xavier, Montana

Kendrick…

Towed a Mennonite-built trailer that he used as a darkroom for six years to 14 Western states covering more than 40,000 miles visiting more than 50 ranches.