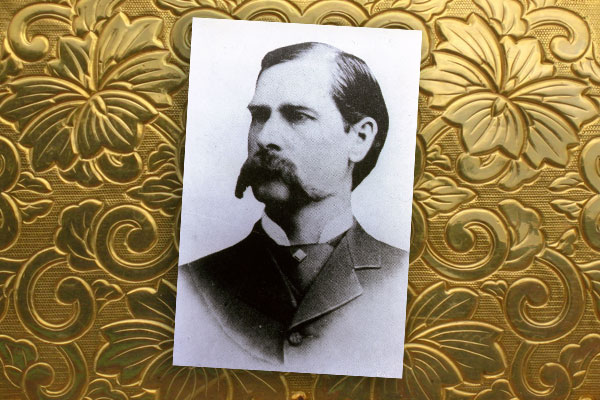

Following the death of her husband, Wyatt Earp, in 1929, at the age of 63, Josephine Sarah Earp, who Wyatt called “Sadie,” spent a great portion of her life defending the old lawman’s reputation. For years, writers and film makers attempted to tell the famous Kansas and Arizona peace officer’s life story, but Josephine’s efforts to control the story of Wyatt’s life and the part she played were successful for over 120 years.

Following the death of her husband, Wyatt Earp, in 1929, at the age of 63, Josephine Sarah Earp, who Wyatt called “Sadie,” spent a great portion of her life defending the old lawman’s reputation. For years, writers and film makers attempted to tell the famous Kansas and Arizona peace officer’s life story, but Josephine’s efforts to control the story of Wyatt’s life and the part she played were successful for over 120 years.

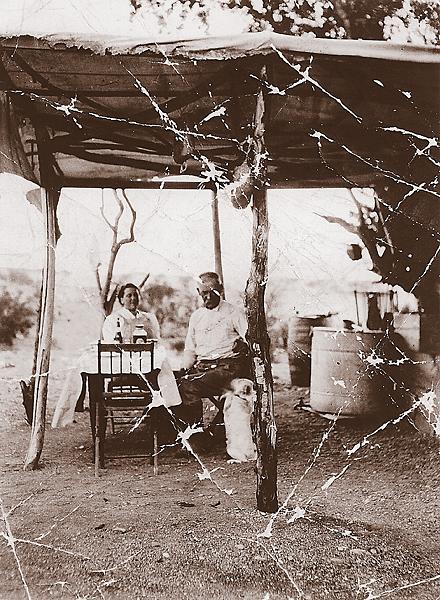

She was a woman who was ornery and frustrating to some but fun-loving and thoughtful to others. She exhibited a dependency toward gambling and displayed a habit of wrapping dollar bills in rolls of toilet paper but, despite her oddities, she was a woman with whom Wyatt Earp chose to spend over 47 years.

Josephine Sarah Marcuse was born in New York, sometime between the latter part of 1860 and early 1861. Her father, Carl-Hyman Marcuse (later changed to Henry Marcus), married Sophia Lewis, a widow eight years his senior with a three-year-old daughter by the name of Rebecca. Their first son, Nathan was born August 12, 1857. Their last child, Henrietta, was born July 10, 1864, a special event for three-year-old Josephine as the two would share a close bond throughout their lifetimes.

The Marcus family remained in New York for approximately five more years when news of a prospering city and the promise of financial security would lead them across the Pacific Ocean, by way of the Panama Canal to the shores of San Francisco. By the time they arrived, the city was recovering from the disastrous earthquake that hit on October 21, 1868. In addition, the transcontinental railroad was nearing its completion causing unemployment to rise as literally thousands of men began to return from building the railroad. At the same time, droves of people were pouring in from other countries.

By 1870, the population reached 149,473, causing overcrowding of apartment buildings and large homes turned into rooming houses. Still, it was a prosperous time for San Francisco since jobs were plentiful and the city was experiencing a healthy economy.

While Henry worked as a baker, Sophia took over the responsibility as wife and mother. It was also a time to celebrate Rebecca’s marriage to 29-year-old Aaron Wiener, an insurance salesman from Prussia. The thriving economy not only offered the promise of a comfortable future, but, by 1873, the greatest silver vein of all time hit causing the stock market to soar.

Everyone in San Francisco was investing in Silver Mania. It was a prosperous time for all, including the Marcus family who could afford music and dance classes for Josephine and Henrietta (Hattie). Both girls were enrolled at the McCarthy Dancing Academy, a family-owned business whose teachers taught both children and adults. It was the juvenile classes Josephine recalled in later years:

“Hattie and I attended the McCarthy Dancing Academy for children on Howard Street (Polk and Pacific). Eugenia and Lottie McCarthy taught us to dance the Highland Fling, the Sailor’s Hornpipe, and ballroom dancing.”

Music lessons were taught by “Mrs. Hirsch,” whose daughter, Dora would become Josephine’s best friend and confidant. She would also become an influential figure that would alter the direction of Josephine’s life. But Josephine’s world would soon change when the vein of the Comstock silver would become depleted causing the stock market to crash. She would later recall this period as the “roller coaster years.”

“I grew up in San Francisco in the seventies — the more extravagantly reckless and disastrous period of the city’s history. This decade saw the rise of the railroad and the bonanza kings and the erection of their enormous wooden castles on Nob Hill. The whole populace enjoyed a few years of feverish delirium brought about by a new strike in the Comstock Lode of Nevada. Those who did not leave town to engage in the hard work of prospecting gambled in the stocks of the mines. But in the latter part of the decade, when this source of wealth began to dry up, when crops failed, and markets crashed, cold sanity returned to town along with poverty.”

By 1874, San Francisco had become a divided class. The occupational progressions were confined to the white-collar sector. Henry’s earnings as a baker were not enough to provide for his family. He and Sophia moved in with their daughter and son-in-law, who, by now, had begun a family of their own.

At the vulnerable age of 13, Josephine’s view of the world and her surroundings would leave a distinct impression in later years that would lean toward histrionic fantasies by claiming her father ran a prosperous mercantile business. She would also describe her home as a “comfortable, prosperous house in a neighborhood where many other Jewish families lived.”

It was an extreme exaggeration from reality, at least during this period in her life. In fact, the crowded wooden cottage (tenement), where the two families shared living quarters was located in the flatlands south of Market Street, also known as “the slot”—a working class, ethnically-mixed neighborhood, where smoke from factory chimneys and the sounds from foundries filled the air; an area surrounded by slums, laundries, machine shops and boiler works. Close by, was South Park and the embarcadero where ships would bring immigrants who would look for work and housing in an area that was already overcrowded.

Years later, one resident and teacher at a local grammar school wrote about the neighborhood: “The scene is a long busy street in San Francisco. Innumerable shops lined it from North to South; horse-dawn street cars always crowded with passengers, hurried to and fro; narrow streets intersected the broader one, these built up with small dwellings, most of them rather neglected by their owners. In the middle distance were other narrow streets and alleys where taller houses stood. And the windows, fire escapes, and balconies of these added great variety to the landscape, as the families housed there kept most of their effects on the outside during the long, dry season. Still farther away were the roofs, chimneys and smokestacks of mammoth buildings – railway sheds, freight depots, powerhouses and the like – with finally a glimpse of the docs and wharves and shipping. All the most desirable sites were occupied by saloons and it was practically impossible to quench the thirst of the neighborhood.”

While the 1870s brought an increasing number of immigrant families who suffered from hunger and sickness, they brought with them a new class of vagrant children who threatened the future order of society. Newspapers printed stories, almost daily, about the problem of “Hoodlumism,” (sic) whereby one or sometimes an organization of young men were caught pilfering houses in certain portions of the city, or would take out their frustrations by harassing the Chinese and smashing business property.

Despite the turbulence within the city, Josephine found solace through two families whose children were her playmates. The Belascos and the Frombergs had enough children between the two families to take up a whole neighborhood. One side was Isaac and Sarah Fromberg with five daughters and two sons. Next door was Abraham and Rayna Belasco with their lot of 10, whose eldest Son David would eventually become a famous playwright.

Josephine’s childhood appeared to be similar to that of other children during these turbulent years, although she claimed to have matured at an early age noting, “there was far too much excitement in the air to remain a child. She described the schools of San Francisco as “inconsistent of a tolerant and gay populous acting as mercilean and self-righteous as a New England village in bringing up its children.” She felt the discipline she received was rather harsh considering the offenses. Whether it was the “sting of rattan” or “being slapped for tardiness” that motivated the 14-year-old girl to run away from home, it was also a turning point in her life, one she would continue to regret throughout her lifetime.

While dictating her memoirs in later years, Josephine related a story of how she and her best friend, Dora Hirsch, ran away with the Pauline Markham Pinafore troupe:

“I kissed my mother good-by [sic] as usual but instead of going to school I went to my friend’s house. The door opened before I knocked. Dora was fully dressed, waiting for me, and ready to go.”

Josephine would relate a story that she and Dora sailed down the coast with the Pauline Markham Pinafore troupe, stopping in Santa Barbara on their way to Arizona. Her detailed account lends some merit however, what Josephine failed to realize was the Markham troupe, consisting of six members, left for Arizona in October of 1879 by the Southern Pacific Railroad, and not by ship. Furthermore, by 1879, at the age of 18, Josephine was old enough to have left home without having to run away. While the story of leaving home offers credibility, the dates of her departure have been misconstrued for many years. Josephine’s memoirs and other sources indicate her departure may have been as early as October of 1874.

After leaving San Francisco, Josephine claimed she and Dora arrived in Santa Barbara where they stayed one night at the Arlington Hotel. The following day, they boarded a stagecoach (in front of the hotel) bound for San Bernardino where they would board another coach headed toward Arizona.

After crossing the Colorado River by ferry, they landed at Ehrenburg where talk of Apache Indians became the main topic of conversation among the passengers. Josephine recalled the frightening event stating, “some renegade Yuma-Apaches had escaped from the reservation to which they had been consigned and had returned to their old haunts on the war-path.”

On October 24, 1874, the Arizona Miner reported, “Al Zieber (Sieber), Sergeant Stauffer and a mixed command of white and red soldiers are in the hills of Verde looking for some erring Apaches, whom they will be apt to find.” Josephine’s recollections of meeting the famous Indian scout, who she claimed led them to a ranch house, described Sieber as having, “sharp deep set eyes, grey buck-skin [sic] garments, alert and full of good-humor, a strong man astride a strong horse.” Although Josephine’s description of Sieiber was fairly accurate, it is doubtful she met him at this time because he (Sieber) would claim in later years that he never wore buckskin garments while chasing Indians. In fact, the only time he would admit to the costume was while posing for a photograph. Nonetheless, Josephine relates the story that Sieber and his scouts led the stagecoach and it’s passengers to a nearby adobe ranch house where they would spend 10 days sleeping on the floor. According to Josephine, it was while being confined at the ranch house when she first met “Johnny Behan” (John Harris) who she described as, “young and darkly handsome, with merry black eyes and an engaging smile.”

John Harris Behan had been nominated sheriff on September 26, at the democratic convention in Yavapai County. It was reported in the Prescott Miner on October 6th that “J.H. Behan left on an “electioneering” tour toward Black Canyon, Wickenburg and other places.” By November 11, he was back in Prescott where he would lose the nomination. However, the 35-day campaign trek could have offered ample opportunity to meet the young Josephine Marcus.

During the 10-day confinement, Behan’s charming personality and attentions were engaging enough that Josephine would later admit, “my heart was stirred by his attentions as would the heart of any girl (would) have been under such romantic circumstances. The affair was at least a diversion in my homesickness though I cannot say I was in love with him.”

It was after leaving the ranch house that Josephine claimed she and Dora went back to San Francisco with the help of Sieber. It was also a time in Behan’s life when his marriage was failing and his political career wasn’t going as well as anticipated, giving him plenty of motivation to keep Josephine from returning home.

During the month of December, Behan was seen by neighbors, on more than one occasion, entering a “house of ill fame,” located on Granite Street, near Gurley in the town of Prescott. The scandal that was the cause of Behan’s divorce months later, also included talk of Behan’s visits and “relationship with” a 14-year-old prostitute by the name of Sadie Mansfield who was residing in the house under the watchful eye of Madam Josie Roland. In addition to similarities in age, records indicate other parallels that would explain why Josephine looked back upon this time in her life as “a bad dream,” and later commented, “the whole experience recurs to my memory as a bad dream and I remember little of its details. I can remember shedding many tears in out-of-the-way corners. I thought constantly of my mother and how great must be her grief and worry over me. In my confusion, I could see no way out of the tragic mess.”

On February 6, 1875, criminal charges were filed against Sadie Mansfield for Petty Larceny. The complaint stated that “one set of German table spoons were stolen from the store of H. Asher and Company in the village of Prescott, Yavapai, A.T.” After a search by Sheriff Ed Burnes was conducted at the residence of Sadie Mansfield, the sheriff confiscated the spoons. The case went to trial the same day with one witness for the defense, Jennie Andrews. The jury of nine men returned a verdict of “not guilty.”

If Sadie’s attempts at taking the spoons (valued at $162.00), was a way to buy her way home, this may have been the time Sieber helped her. He was a popular figure in Prescott and well liked by the town folks. According to Josephine, Sieber contacted her brother-in-law through military telegraph (located at Fort Whipple). Josephine and Dora left Prescott, escorted by a family friend to San Bernardino. When they arrived, Aaron Wiener was waiting to take them home.

The exact date of Josephine’s return home is unclear but she stated she was in San Francisco in time to attend the Grand opening of the Baldwin Theater on March 6, 1876. Her family wanted to keep her “escapades from the public.” In her memoirs she wrote, “the younger children (niece and nephew), and our friends were told that I had gone away for a visit. Mrs. Hirsch, because of Dora’s part in it was as anxious as my people (family), to keep it a secret. The memory of it has been a source of humiliation and regret to me in all the years since that time and I have never until now disclosed it to anyone besides my husband (Wyatt).” The experience, she claimed was so exhausting, she was not able to attend school again.

By November of 1879, Johnny Behan had gone into the saloon business in a silver mining town known as TipTop in Arizona. The town had six saloons with five courtesans, Johnny’s being the one short. By February of 1880, Sadie Mansfield was on her way to TipTop. According to Josephine, Johnny’s proposal of marriage was a good excuse to leave home. She wrote, “life was dull for me in San Francisco. In spite of my bad experience of a few years ago the call to adventure still stirred my blood.” By now, The Pauline Markham Pinafore troupe was performing in Prescott on Whiskey Row.

In September of 1880, Johnny Behan left TipTop for Tombstone where he would become a partner in a livery stable, the Dexter Corral. He would also keep his bartending skills sharpened while serving drinks at the Grand Hotel, a convenient establishment that could offer comfort for anyone, including Sadie. By November, Johnny had been appointed deputy sheriff under Charles Shibell and was a back-slapper among the political arena in Tombstone. With Sadie working for Behan at the Grand Hotel, it wouldn’t have taken long for Wyatt to become acquainted with Behan’s girl. Furthermore, in all likelihood, Wyatt’s relationship with Mattie (possibly a common-law marriage) was disintegrating when the striking Sadie caught his eye. Wyatt’s attentions toward Sadie may have prompted Johnny’s decision to set up housekeeping with Sadie.

It was also an added convenience to use her as a full-time baby-sitter for his 10-year-old son, Albert, who had arrived in Tombstone on May 2, 1881, registering as a guest at the Grand Hotel.

According to Johnny’s former wife Victoria, Johnny had a side to his personality that, while under the influence of alcohol, he became “cruel and abusive.” This may have been why Sadie left Behan and moved into a boarding house until the summer of 1882. In the meantime, Wyatt left Tombstone after the historic O.K. Corral shoot-out and eventually ended up in San Francisco with his brothers Virgil and Warren where he would wait for Sadie. By January of 1883, Sadie left San Francisco for the last time. She and Wyatt would head for the mining camps in various parts of the country until their retirement in Los Angeles in the 1920s. After Wyatt died, Josephine refused to let anyone call her Sadie.

By February of 1937, Josephine Earp left Los Angeles for Tombstone Arizona for the purpose of gathering information to begin her memoirs. After she registered at the Tourist Hotel she sat in a small room overlooking Fifth and Allen Streets where it all began:

“The years rolled back on my shoulders, and my friends departed. I was alone — alone in the dark hotel room, looking out to the drug store where Wyatt Earp had once been an owner of the luxurious Oriental gambling palace. Tears were coursing silently down my cheeks as I looked onto deserted streets with its neon signs. I don’t know how long I stood there, dreaming. The old scene had faded — all had gone except one — the figure of a quiet, dignified man standing there so quiet and lonely.”

Josephine Earp died on December 19, 1944. Her ashes are buried beside her husband Wyatt Earp, in Colma California.

Photo Gallery

– courtesy Jeff Morey –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin collection –