— Courtesy Karges Family Trust —

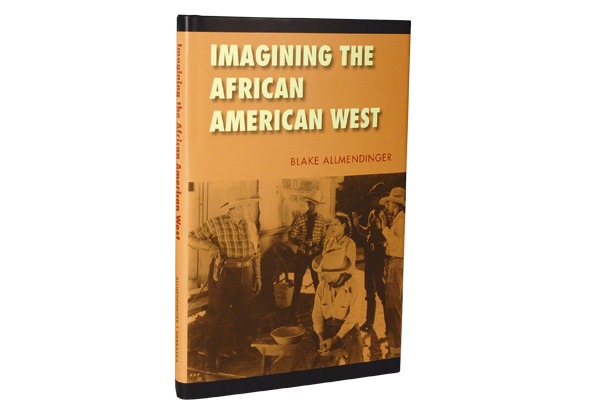

“Maynard Dixon’s American West” is based on Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West’s “Maynard Dixon’s American West” exhibition, which debuts October 14, 2019, and Mark Sublette’s accompanying catalog Maynard Dixon’s American West: Along the Distant Mesa (Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona, 2019).

Maynard Dixon

Under the Sign of the Thunderbird

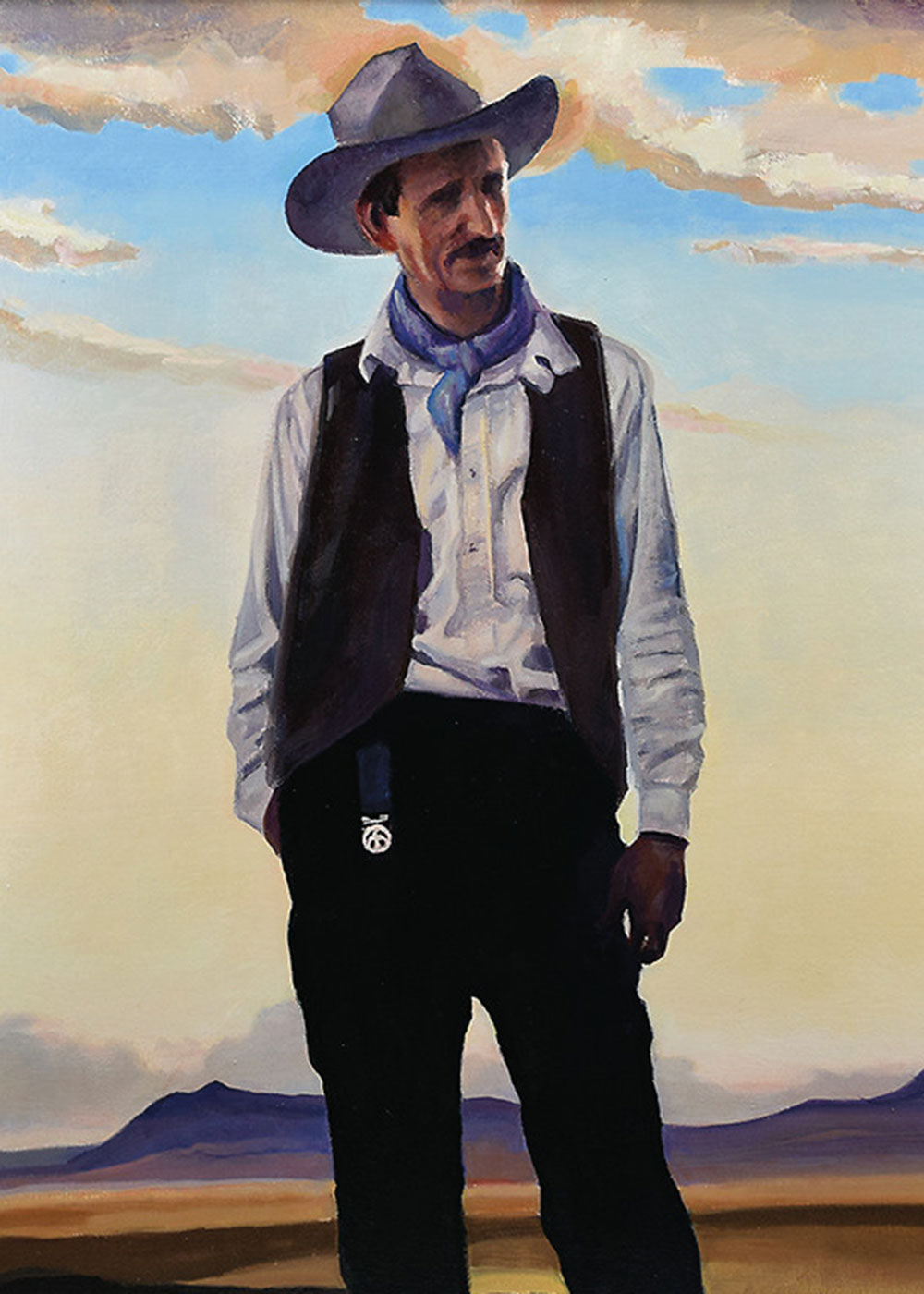

Maynard Dixon, born on January 24, 1875, in the budding cattle town of Fresno, California, grew up during the twilight of the frontier American West. During his childhood the Indian wars still raged, cowboys rode the range, rodeos emerged, a new artist named Fredric Remington appeared on the scene, great stretches of untouched wilderness remained, and the “Vanishing American” did anything but vanish.

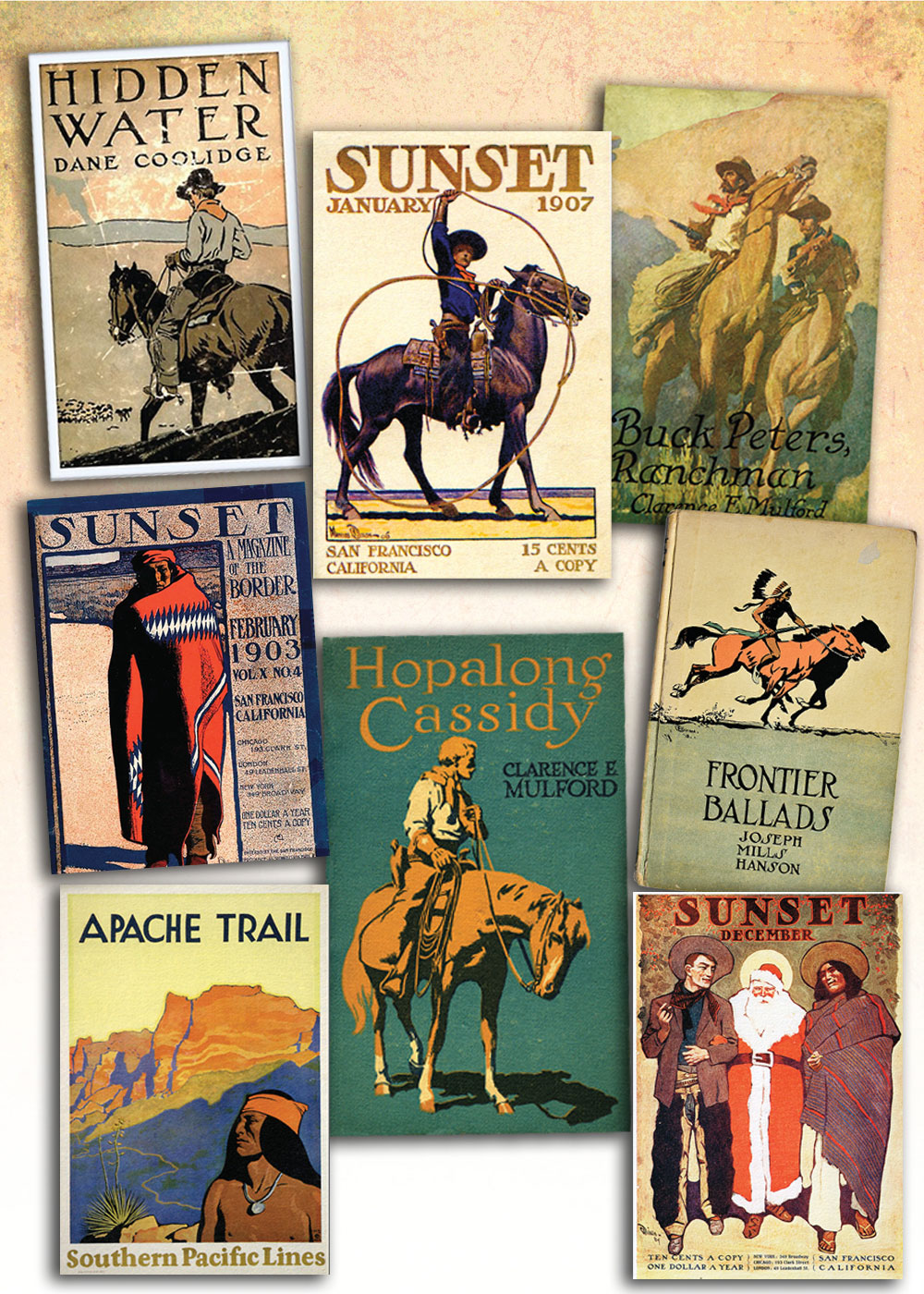

Young Dixon observed, became intrigued by, and in due course captured much of what he experienced firsthand, continuing to do so for decades thereafter. Although he became known for his stunning landscapes, Dixon’s art and illustrations often depicted the mosaic of the men and women who peopled the West. During the course of his prolific career, Dixon managed to produce a great catalog of highly collectible and critically acclaimed art. He also realized, like master artists Remington and Charles M. Russell, that he could make a steady income as an illustrator. Dixon rendered dozens if not hundreds of magazine covers and illustrations for popular novels, such as Clarence Mulford’s Hopalong Cassidy series that launched in 1904.

— All Images Courtesy Mark Sublette’s “Maynard Dixon’s American West”, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona, Unless Otherwise Noted —

Starting in 1900, Dixon crisscrossed the Southwest, when he visited Arizona and New Mexico.The following year, he took a rugged horseback trip with artist Edward Borein through several other states. He did more than pass through the landscape, which had long captivated him. Except

for a short stint in New York City, Dixon resided in San Francisco, California, making frequent forays to such inspirational locales as Zion National Park and Mount Carmel, Utah, a hamlet where eventually he periodically escaped to his cabin-studio retreat.

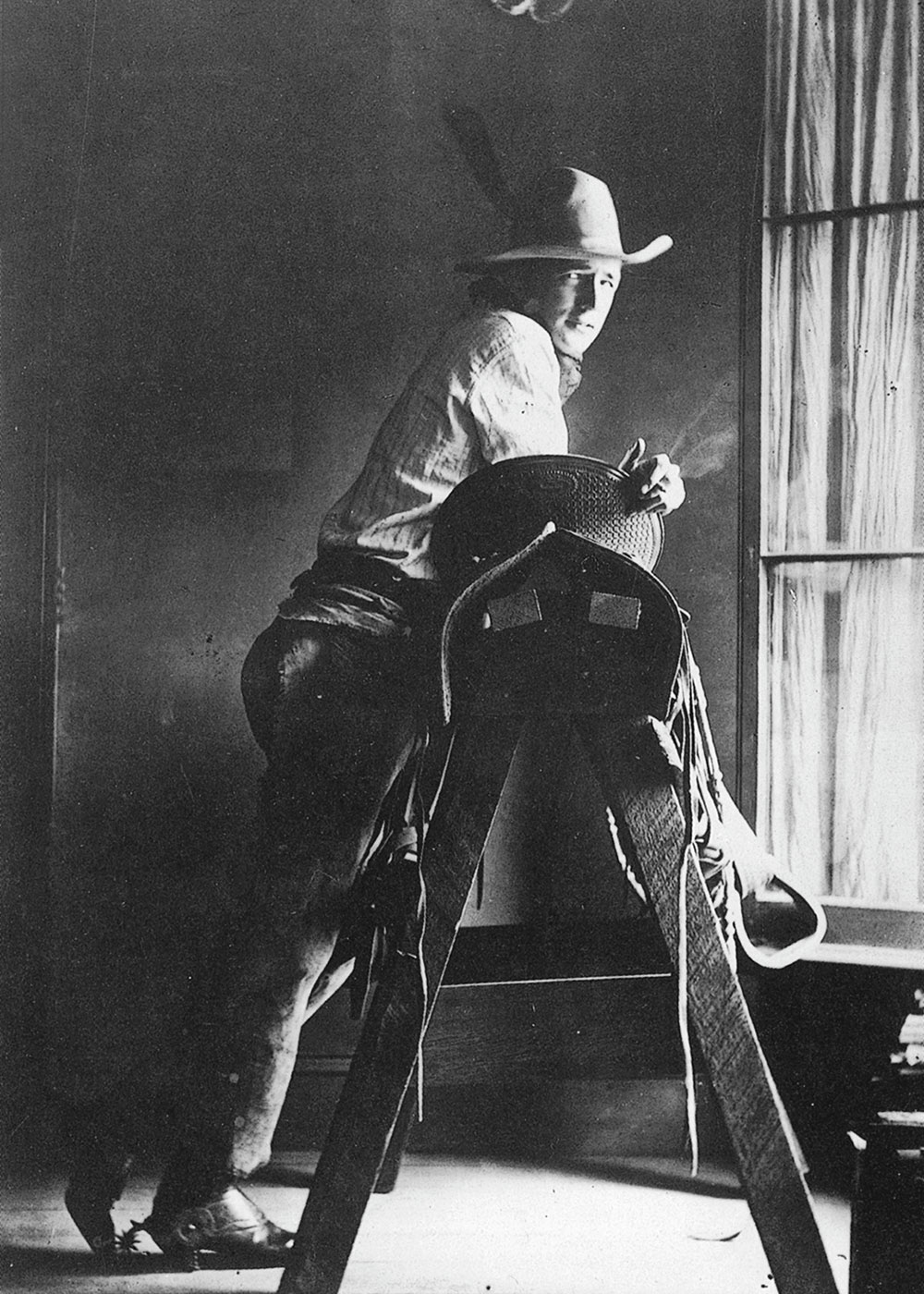

Often donning cowboy boots and a tall crowned Stetson, along with adopting the symbol of the Thunderbird as his personal talisman, the rawboned Dixon remained ever the Westerner. Indeed, he spent his final days in Tucson, Arizona, gazing out of the large picture window in his parlor that framed the Catalina Mountains as an inspiration. There, Maynard Dixon died on November 11, 1946. His vison lives on in the Maynard Dixon Museum in Tucson and the Maynard Dixon Living History Museum in Mount Carmel, in museum collections around the world, in the homes of individual collectors and in select galleries that highly prize his work nearly 75 years after his death.

— Courtesy Zaplin Lampert Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico —

As director of research and publications at the Autry Museum of the American West, John Langellier oversaw the compiling and editing of The Thunderbird Remembered (1994). He presently is completing a study of the intersecting lives of Lieutenant Powhatan, 10th U.S Cavalry and Frederic Remington.

— Courtesy California Historical Society, Sacramento, California —

The Wandering Lunatic

As a mere boy, Maynard Dixon, 16, sent some of his drawings to his hero, Frederic Remington, and got this reply: “You draw better at your age than I did at the same age—if you have the ‘sand’ to overcome difficulties you could be an artist in time.”

The term “sand” is an American frontier expression conveying stamina and courage.

Leaving his home in Fresno, California, Dixon traveled down to El Alisal, on the Arroyo Seco, six miles out of Pasadena and met Charles Lummis who assigned him to take a road trip east, to find the true West.

— Courtesy collection of the California State Library at Sacramento —

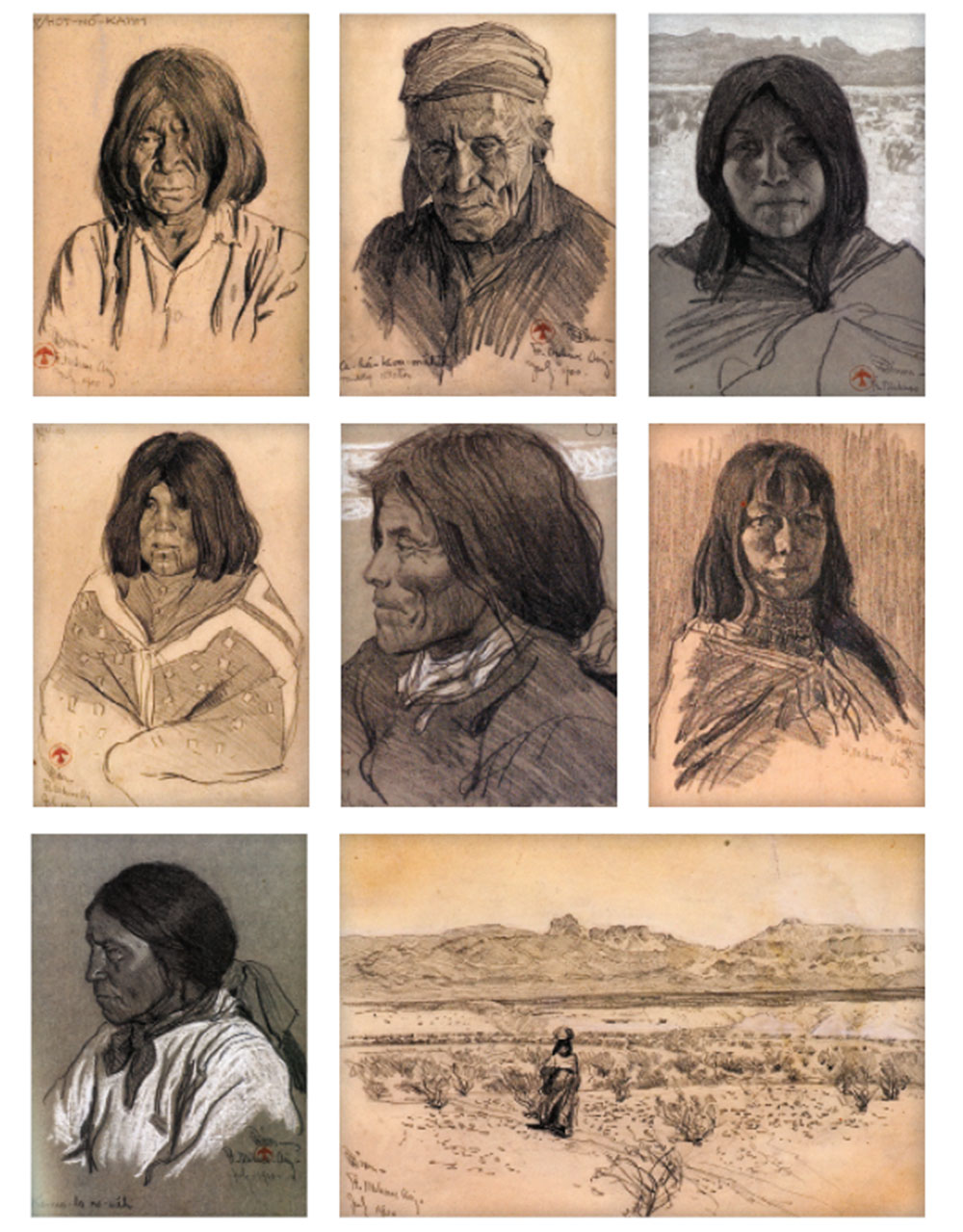

Maynard launched himself east, by train, and landed in Needles, California, in July of 1900. He was determined to draw the people he met, especially the Mojave Indians and he found them, up the Colorado River, at Fort Mojave where the average temperature in the shade was 120 degrees! Here are a few of the sketches he made (opposite), on the banks of the Colorado River.

From Fort Mojave, Dixon went further into Arizona (still a territory!) and sketched his way from Prescott (where he stayed with the family of Arizona historian Sharlot Hall), down to Jerome, Camp Verde and Phoenix. Everyone he met thought he was crazy.

“In those days in Arizona being an artist was something you just had to endure—or be smart enough to explain why. It was incomprehensible that you were just out ‘seeing the country.’ If you were not working for the railroad, considering real estate or scouting for a mining company, what the hell were you? The drawings I made were no excuse and I was regarded as a wandering lunatic.”

—Maynard Dixon

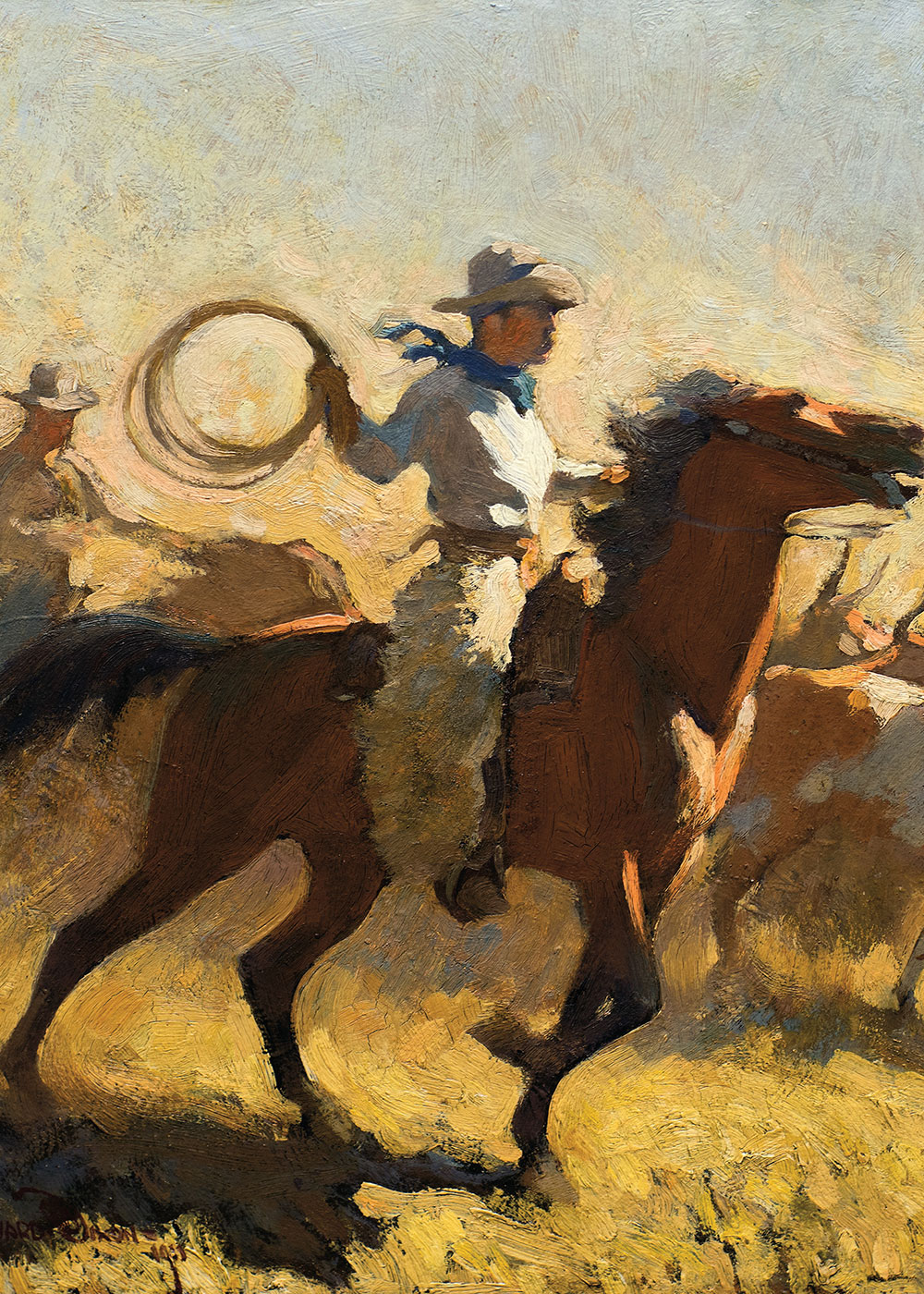

On the Cowboy Trail

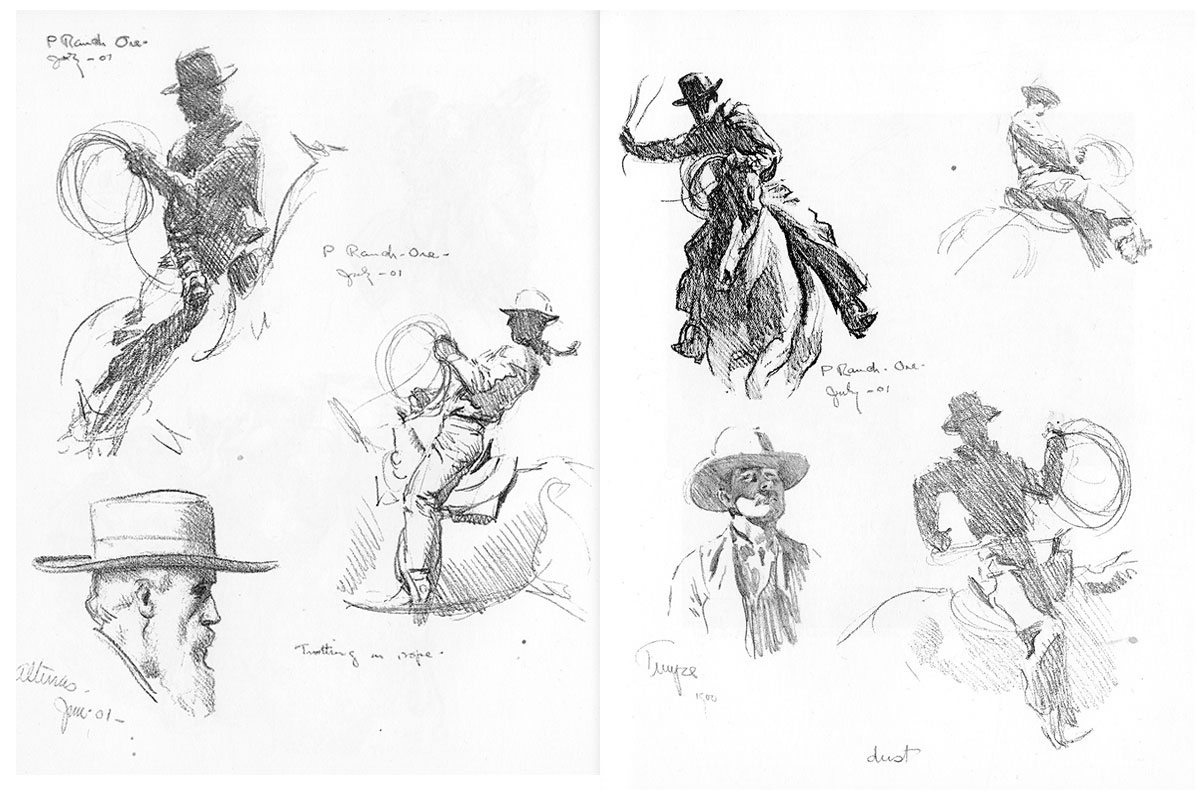

In May of 1901, Maynard and his artist friend, Edward Borein, took off from Oakland on horseback, bound for Montana. Averaging 25 miles a day, they rode through Carson City and Reno, Nevada. From there they headed north into southeastern Oregon. They spent two months on isolated ranches, including the P Ranch, where Dixon made rapid pencil sketches. These gesture drawings are brilliant in their simple lines with dashed off detail done with precision and skill.

— Courtesy American Museum of Western Art, the Anschutz Collection, Denver, Colorado —

— Courtesy Private Collection —

— Ulrike Kantor Collections from Donald J. Hagerty’s The Art of Maynard Dixon —

The Cover Boy

Over the span of several decades, Dixon’s strong design sense and captivating artwork appeared on dozens and dozens of magazine covers and numerous book jackets.

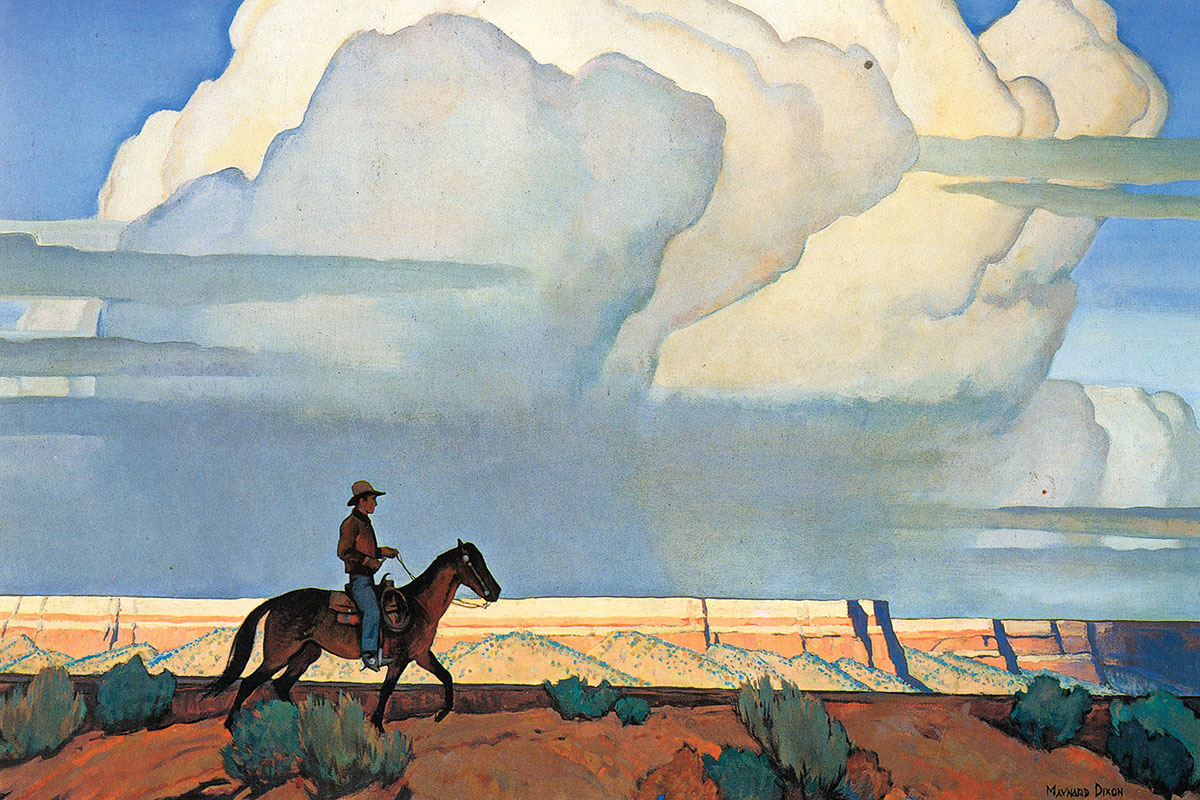

Dixon didn’t shun modernist views in art. In fact, he resigned from the influential Bohemian Club in San Francisco because of the criticism of his modernist infusions into his artwork. Dixon was a progressive leader in the San Francisco art world in the 1920s. As Dixon’s biographer, Don Hagerty put it, “Dixon believed in the sure inspiration of nature, but also made emphatic statements that championed abstract painting.” This is exactly what gives his artwork power and why it resonates to this day.

The Muralist

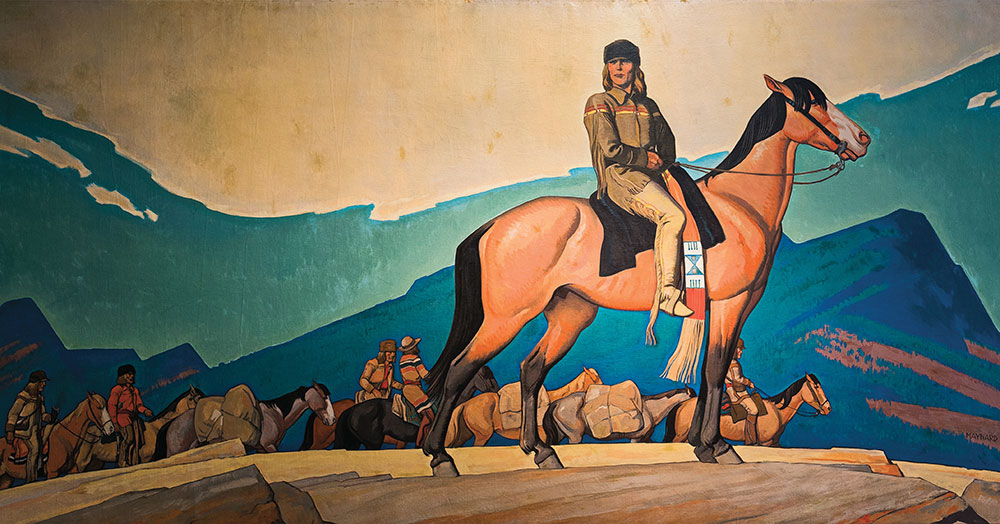

During his career, Maynard Dixon painted between 25 and 30 murals. Two were on steamships that have been lost and several have disappeared through the years. In addition to murals at train stations in Tucson and Los Angeles, Dixon painted two huge murals for the Kit Carson Grill in San Francisco, California. Fortunately for preservationists, the murals were painted on canvas and then glued to the wall. Both murals have been saved and one of them is in the Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West in Scottsdale, Arizona, and the other is at The Booth Museum in Cartersville, Georgia.

Maynard spent some time in New York and was successful there, but he didn’t like how Western publishing and storytelling had become so exaggerated. He wrote to Lummis, “I’m being paid to lie about the West. I’m done with all of that. I’m going back home where I can do honest work in my own way.”

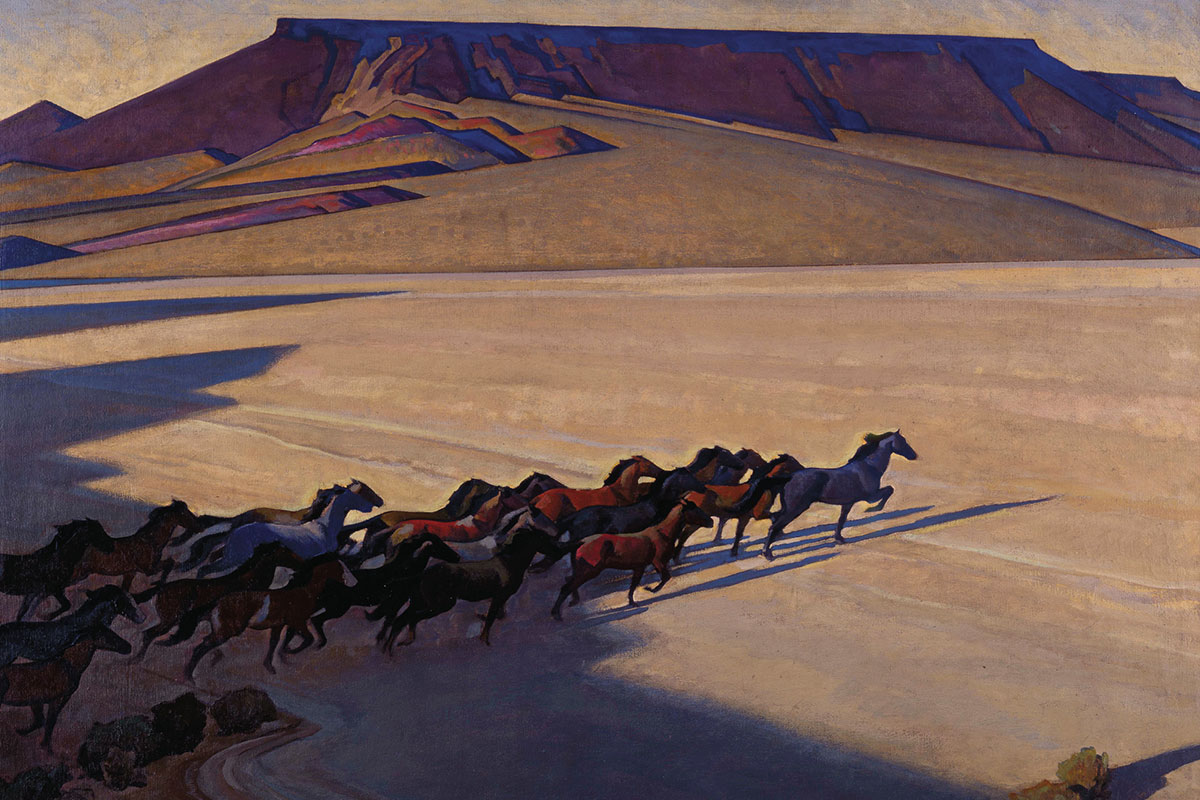

The Monumental Murals at the Kit Carson Grill

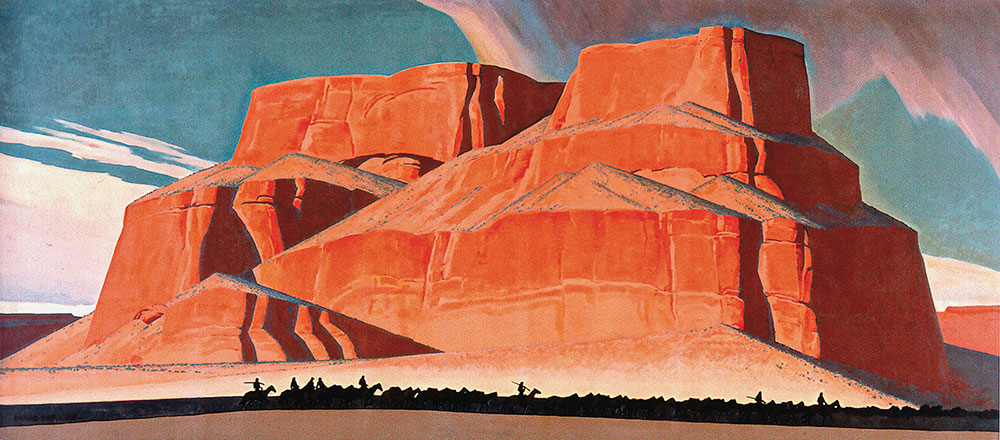

Near the end of 1935, Maynard landed two big mural commissions at the Kit Carson Grill in San Francisco’s theater district. The first, Kit Carson with Mountain Men, and the second mural, Red Butte with Mountain Men, also covered an entire wall in the restaurant.

Distinctive teepee place mats were at each table and could be folded and mailed as a postcard. These unique items told the story of the murals that were the major attraction of the grill. The Kit Carson Grill closed (but fortunately its Dixon murals were saved) to be replaced by a string of new eateries. Today this prime space next to Union Square is occupied by the 398 Restaurant and Bar.

—Courtesy the Peterson Family Collection, Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West/Photo by Loren Anderson Photography —

The Long Road to the Booth

In 2001 the Booth Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, was just getting off the ground when Executive Director Seth Hopkins was contacted by an art dealer out of Florida who offered two murals by Maynard Dixon done for the Kit Carson Grill in San Francisco. Originally, the two were to be sold together, but, according to Hopkins, the Booth chose Red Butte and then built one of the galleries around the painting, which measures a staggering 8 feet by 18 feet. Visitors often sit in front of it for long periods, studying the scale and the details. They say it’s worth flying across the country just to see it. In person you can make out every single horse in the long procession.

— Courtesy Booth Western Art Museum, Cartersville, Georgia —

The Fine Artist

Maynard Dixon earned his spurs on several fronts. He did his due diligence (see the Wandering Lunatic, page 68), he escaped the ghetto of being labeled an “illustrator” and he showed his skill on a couple dozen monumental murals. But, more importantly, he blew the roof off of Western art and took the genre to a new and modern level that Remington and Russell did not. As Dixon himself put it, “The artist’s job, as I see it, is to try to widen people’s horizons—show them the wonder of the world they live in.” You might make a case that there are better painters, but in the end, Maynard Dixon is the West’s greatest artist. He made the transition to modern art with integrity and authenticity.

Oh, and he had sand.

— Courtesy “Maynard Dixon’s American West,” Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona —

“The melodramatic Wild West idea is not for me the big possibility. The nobler and more lasting qualities are in the quiet and most broadly human aspects of western life.” –Maynard Dixon