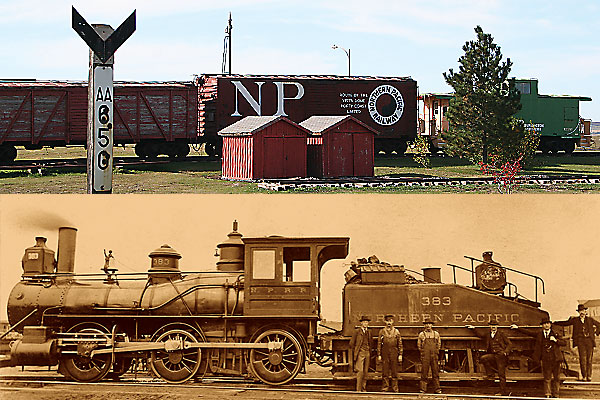

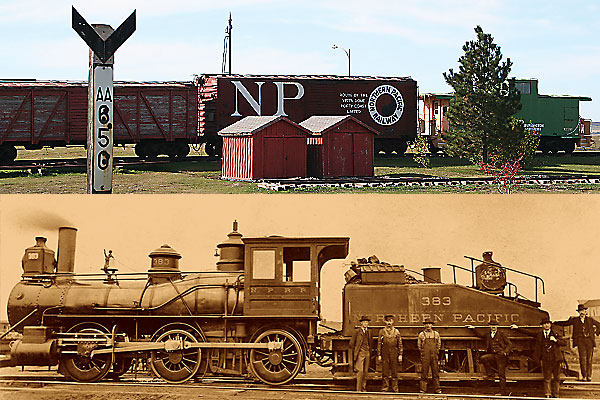

St. Paul, Fargo, Jamestown, Bismarck, Glendive, Billings, Livingston, Bozeman, Missoula, Sandpoint, Spokane, Yakima, Tacoma. These are some of the largest towns in the Northern Plains and Northwest, all either spawned—or given a growth hormone—by the construction of the Northern Pacific Railway that went into service 125 years ago.

President Abraham Lincoln chartered the line on July 2, 1864, as the first northern transcontinental railroad through a region where few communities existed. The twin rails eventually stretched west from the Great Lakes to Puget Sound, traversed the North Dakota Badlands and Montana’s eastern prairie, and climbed across (or through) the Continental Divide separating western Montana and Idaho and the Cascades in Washington. Once construction started, 20 years passed before the line overspread the general route pioneered by Lewis and Clark. [view map]

Like the rugged terrain, the railroad development itself had peaks and valleys. It was affected by financial swings including the Panic of 1873, takeovers and reorganizations. When the final spike linking the road was hammered home at Gold Creek, Montana Territory, on September 7, 1883, the Northwest still had vast areas populated by few people. Much of the area remained territorial-statehood would come in 1889 for North Dakota, Montana and Washington, and in 1890 for Idaho. Minnesota had been a state since 1858.

Groundbreaking for the eastern section of the line started in 1870 near Carlton, Minnesota. During the next three years, crews pushed west from Duluth to Bismarck, in Dakota Territory. Simultaneously western crews began building from Kalama to Tacoma-a town organized to serve the railroad-in Washington Territory. Jay Cooke, the Civil War bond financier, played the first pivotal role in the development of the Northern Pacific, pushing the line west across Minnesota and into North Dakota during his three years of company management.

To follow this route, we will begin in Minnesota where the first trains began running between St. Paul and Forest Lake on December 23, 1868. With new bonds issued and under Cooke’s fiscal control, construction picked up. Two years later, the 155-mile run between St. Paul and Duluth was in place. By 1871, the line had been completed across Minnesota and had spanned the Red River at present-day Fargo.

The eastern terminus was at the confluence of the Minnesota River with the Mississippi-the present-day city of St. Paul. Fort Snelling (first called Fort Anthony), completed along the riverbank by 1825, became an important American outpost leading to settlement of the Northwest frontier. Dakota and Ojibwe Indians traded at the post, as did fur trappers and traders. In time, it became the supply base and headquarters for the army’s Department of Dakota.

By 1851, much of Minnesota Territory had been opened to settlement and newer forts established as Fort Snelling became a supply depot. Today, the re-created post offers living history programs on the frontier and Civil War military. (The Upper Bluff contains 28 original buildings, which were listed as among the most endangered historical sites by the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 2006.)

As the tracks of the Northern Pacific overspread the prairie and pushed into lands occupied by the Sioux, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered military troops into the field to protect crews both surveying and building the line. In May 1872, troops from Fort Ransom, Dakota Territory, marched west, carrying 40 days’ rations. The soldiers camped where the Northern Pacific rails would transverse the James River. They were on the lookout for Sitting Bull and his Hunkpapa followers, whose last hunting grounds was the very same Yellowstone Valley where tracks were being laid.

Protecting North Dakota

My route heads west across North Dakota on Interstate 94, a highway nearly as straight as a rail line, before it sweeps through farmland west of Fargo. My first major stop is at Jamestown, situated along the James River. The troops ordered there to survey and protect track layers established Camp Sykes, named for Col. George Sykes of the 20th Infantry but soon called Fort Cross and then renamed Fort William H. Seward on November 19, 1872. This final and permanent name for the post came to recognize the Secretary of State during the Lincoln administration (and the man responsible for purchasing Alaska from Russia).

Built on a ridge above the James River, Fort Seward consisted of more than 30 buildings including barracks, a company kitchen, mess room, hospital, guard house, three officers’ quarters and four sets of laundresses’ quarters. No original buildings remain at Fort Seward, which was in use from 1872 to 1877, but you can see the locations of building foundations and learn about the post at the Fort Seward Interpretive Center.

Jamestown is also home to Frontier Village, a collection of historic buildings from the region that now sit adjacent to the National Buffalo Museum, where you will have an opportunity to see White Cloud, a white buffalo revered by area Indian tribes.

From Jamestown, continue west on I-84. The rails reached Bismarck in 1873. Indian villages had been situated at this site along the Missouri River for many generations, at places such as the Double Ditch Indian Village and Chief Looking’s Village, where you will see indentations in the earth indicating the former locations of lodges.

At On A Slant Village, west of the Missouri in Mandan, reconstructed earth lodges show visitors what the village would have been like when occupied by the original inhabitants beginning in about 1575. Situated in a protected area with the Missouri River to the east and a cut bank on the north, On A Slant once was the home of Sheheke, a Mandan chief born about 1766, who had met early explorer David Thompson in 1897 and also provided aid to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark when they reached the area in 1804. By that time, the Mandans had abandoned On A Slant (doing so after a smallpox epidemic in 1781) and relocated to a new village upriver.

Camp Hancock, now a state historic site in Bismarck, was established in 1872 in advance of the railroad track layers. This camp was expected to be a temporary post that would serve the Northern Pacific crews as they moved across North Dakota, but Cooke’s efforts to build the line failed on September 18, 1873, when his banking company, having overextended itself, closed, precipitating the Financial Panic of 1873.

Since it was at the end of the tracks, Camp Hancock soon became a supply depot for nearby forts and the Northwest Territory. Today, its exhibits share how pioneers used it as a railroad supply point and a weather monitoring station.

Across the Missouri, in 1872, the military established Fort McKeen, building blockhouses and other structures to better serve the troops who preceded the Northern Pacific survey teams and tracklayers. Fort McKeen’s blockhouses have been rebuilt on the hillside above the Missouri River, giving a commanding view of the region. This post predated nearby Fort Abraham Lincoln where original buildings are restored.

In 1873, Fort Lincoln became head-quarters for the Seventh Cavalry and home to Lt. Col. George A. Custer and his wife Libbie. A central hub during the railroad survey and construction era, this post acted as a distribution point for supplies brought into the region on steamboats plying the Missouri River.

Facing financial difficulties, the tracks dead-ended at the Missouri River in 1872. When construction resumed, the workers ferried railroad supplies across the river. During winter, they laid the tracks right on the ice. By 1882, the company had reorganized as management shifted from Cooke to Henry Villard. That year, the railroad bridge across the Missouri River was completed at Bismarck. This original bridge still spans the Missouri between Bismarck and Mandan, providing a tangible link to the past for both communities.

Down the Line to Montana

Railroad surveys and track construction pushed across the Dakota Badlands and into Montana Territory at Glendive. My route through western North Dakota and across the Badlands is on I-84. From Glendive, the tracks followed the Yellowstone River toward the west. I take Interstate 94 and then Interstate 90 toward Billings, named for railroad president Frederick Billings. I?then head on to Livingston, where the rail line arrived in January 1883.

Take time to visit the Makoshika State Park near Glendive, an area of badlands and dinosaur remains. Near Billings, view Pompey’s Pillar, so named by William Clark when he and some members of the Corps of Discovery spied the rock outcrop on their return journey of 1806. Livingston became an important stop on the early Northern Pacific, especially after company officials established the Yellowstone Branch of the line, providing easy access to Yellowstone National Park, America’s first national park, established in 1872 with support from Jay Cooke and other Northern Pacific representatives.

You will find a good meal at the Stockman in Livingston, and this is an ideal place for an overnight stay as well (I recommend the Murray Hotel in Livingston or the Grand Hotel in nearby Big Timber). Visit the Livingston Depot Center, a building constructed by the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1902, which now houses a museum with exhibits and photos about the line.

Railroad construction crews-including more than 4,000 men, some 2,600 of them Chinese laborers-found it difficult to build the line through western Montana, digging or blasting cuts and tunnels, as the tracklayers crossed Bozeman Pass to the town named for John Bozeman and pressed on to Missoula.

Northern Pacific Railway construction began at both eastern and western terminuses, and the two ends joined near Gold Creek, Montana Territory, about 60 miles east of Missoula on August 22, 1883 (although the official celebration of the road’s completion did not take place until September 8). While Northern Pacific officials attempted to keep secret the earlier joining of the rails, about 500 people gathered on that day in August when the “unofficial” completion occurred. They arrived in “carriages and dashing turnabouts,” and were “flitting hither and thither over the freshly mowed greensward,” a Missoula newspaper reported. Upon the joining of the rails, a boxcar from Seattle traveled east over the line. The first east-to-west-bound transcontinental train arrived in Portland on September 11, 1883, marking the official beginning of service on the entire length of the Northern Pacific.

From Missoula, drive Highway 200 northwest along the Clark’s Fork River to Sandpoint, Idaho. This is one of the more scenic areas of the Northern Pacific route, which passes through tunnels, follows the river and skirts Lake Pend Oreille. In Sandpoint, you will find plenty of shopping, dining and lodging opportunities.

Stampeding to Washington

From Sandpoint, take U.S. Highway 2 and descend into the Spokane Valley of eastern Washington. Explore Riverfront Park before you continue west. Take I-90 west to Ellensburg and then Seattle and Tacoma.

The railroad headed toward Pasco and then chugged through the Yakima Valley on the way through the Yakima Canyon to Ellensburg. When the line reached the Cascades, it became necessary to build switchbacks in the steepest sections over a route known as Stampede Pass (so named when workers “stampeded” back to Seattle after hearing they would be forced to work even harder). The Stampede Pass line was in place on June 1, 1887, but the following year, workers hired by Nelson Bennett of Tacoma completed the “Stampede Tunnel,” eliminating the switchbacks.

Unlike the Union Pacific, the Northern Pacific Railway received no government loans to effect construction, although 44 million acres were provided in the largest land grant ever approved for a single rail line development. The railroad financiers promoted the land-beginning with Jay Cooke who advertised a temperate climate and attracted hundreds of Scandinavian families to North Dakota. German settlers also took advantage of the land grants, settling across both North Dakota and Montana. In Washington, railroad financing came in part through sales of land grants to logging companies.

Amtrak offers three routes that make up the Northwest’s major railroad offerings today: the Cascades, Coast Starlight and Empire Builder.