Romaine “Romy” Lowdermilk, the “Father of Dude Ranching in Arizona,” blossomed into one of the West’s greatest early balladeers.

Born in Kansas in 1890, he was three when his father died. By age 15, he was taking care of a remote windmill and the cattle water tank on a New Mexico ranch. His love for wide open spaces brought him to Arizona, where he hired out as a cowhand for $30 a month. There, he taught himself to play guitar and began learning old-time cowboy songs.

At the age of 21, he homesteaded with his mother, Katherine, naming their 160 acres on the banks of the Hassayampa River, north of Wickenburg, for her: Kay El Bar. Romy turned his one-man working ranch into a dude ranch, the first in Arizona.

In his spare time, Romy wrote a weekly column on humorous cowboy philosophy for a newspaper in Prescott, as well as Western tales for pulp magazines. He strummed his guitar and sang cowboy songs for locals and visitors. When he tired of warbling tunes, he whipped out a lasso and exhibited his rope spinning skills. For added entertainment, he spun the rope while walking on a tightwire.

One night in 1922, Romy, with two friends, performed a song he had written, “Big Corral,” at a talent show in Wickenburg. Meant to be a joke about the chuckwagon cook, the whimsical tune came from a gospel song, “Press Along to Glory Land.”

Cowboy songwriters sometimes failed to copyright their works, as was the case with Gail Gardner, on “Sierry Petes (or, Tyin’ Knots in the Devil’s Tail).” Since Romy did not put his name on “Big Corral,” folks thought it was a traditional song.

In 1924, he had a brief fling with Hollywood when one of his novellas, Tucker’s Top Hand, became a silent movie. He wryly commented, some 40 years later, “The less said about my horse opera the better.”

The year 1924 was also when Romy became friends with John I. White, a University of Maryland graduate who was visiting his brother in Wickenburg. Romy introduced White to John Lomax’s Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, and the pals exchanged songs while sitting around the corral or beneath the shade of a mesquite tree.

Romy continued to write more than 100 Western songs. One of his most famous, “Back to Old Arizona,” is better remembered as “Back to Montana,” recorded by Patsy Montana in 1935.

“Patsy liked it,” Romy explained, “and wanted to sing it on her road appearances, so I just called it ‘Back to Old Montana.’ She recorded it for Victor, and it was on the jukeboxes for quite a spell. You can sing it ‘Back to California,’ or Oklahoma or Wyoming—or any damn place you want to go back to.”

Romy sold the Kay El Bar in 1927. The following year, his friend White sang as the “Lonesome Cowboy” at the Madison Square Garden rodeo. Before long, with the help of radio, White was introducing the genre to millions of Americans.

Meanwhile, Romy ranched at Soda Springs, Coyote Basin and Rimrock. In the late 1920s, he worked a two-year gig with the Arizona Wranglers at the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, during which he performed “Back to Old Arizona.” The Wranglers headed to Los Angeles and, in 1931, recorded Romy’s song.

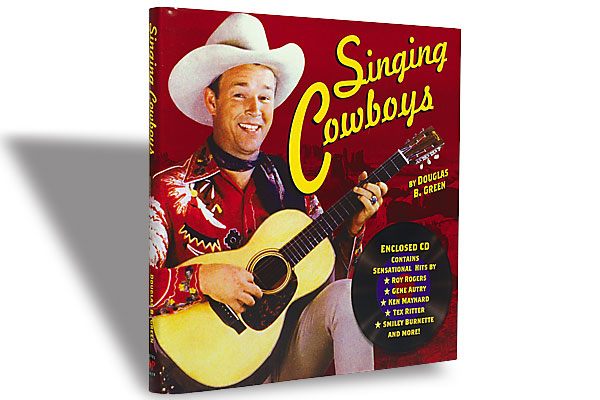

During the mid-1930s, Romy performed on the popular WLS National Barn Dance in Chicago. He not only sang the songs, but also, in the tradition of folk music, explained their meaning. For instance, Gail Gardner once explained how singing cowboys “bitched up” the lingo in his “Sierry Petes.” Singing cowboys of the 1920s did not know the meaning of “seago” from the line: “Now one fine day ol’ Sandy Bob, he throwed his seago down, said, ‘I’m sick of the smell of this burnin’ hair and I allows I’m a goin’ to town.’”

A seago is short for a seagoing rope, but the ignorant singing cowboys substituted words unrelated to ropes. Gardner described ’em as, “They didn’t know which end a cow gets up first!”

In the early 1940s, Romy bought the Howard Ranch in Cave Creek and renamed it Rancho Manana. Today, the Tonto Bar and Grill is located on the ranch site.

While the songs Romy performed brought him a little money and fame, he never made a dime off of “Big Corral.” Even his friend, White, failed to credit him as the writer in White’s 1929 folio of traditional cowboy songs. Romy had to wait until a 1967 article published by The Arizona Republic before he was recognized as the author. Nearly a century later, the song remains a staple for Western singing groups.

Musicologist Charles Haywood listed “Big Corral” as one of only five authentic cowboy folk songs in the 1951 edition of A Bibliography of North American Folklore and Folksong. The other four were “Home on the Range,” “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” “Goodbye Old Paint” and “Echo Canyon.”

A humble man, Romy claimed he never made any commercial recordings, published in White’s 1975 anthology, Git Along Little Dogies: Songs and Songmakers of the American West. Romy had already met his maker by then, having died in Phoenix in June 1970 at the ripe-old age of 80.

In the 1990s, that windy unfurled. Stephanie Hall worked at the American Folklore Center at the Library of Congress. When she told the director, Alan Jabbour, that her brother knew a man in Austin, Texas, who owned a recording by Romy Lowdermilk, the director exclaimed, “Romy Lowdermilk! Who’s got a record by Lowdermilk?”

Sometimes that’s the way treasures are discovered. The American Folklore Center wound up owning the 33 rpm acetate disc featuring 13 of Romy’s songs. For years, the center believed it was a one-of-a-kind disc.

Then came Clay Thompson’s November 2006 column for The Arizona Republic. Norm Johnson had written in to find out more information about an LP by Romy. When researcher Stephen Winick read the article, he got in touch with Johnson and found out his disc was identical to the one at the center. Romy had recorded both at Ramsey’s Recording Studio, in Phoenix, which became Audio Recording Studio in 1957.

During Winick’s search for Romy’s music, the Arizona Music and Entertainment Hall of Fame put the researcher in touch with Arizona music historian John P. Dixon. Romy had performed in at least two recording sessions, in 1951 and 1955, Dixon recalled, one with 13 songs and the other, 10.

Each session contained two versions of several songs, including songs never cut to an acetate. Dixon believes Ramsey made a master tape of the songs that Romy wanted his fans to hear, and those were the songs recorded on acetates, which Ramsey cut on a lathe in real time according to customer orders.

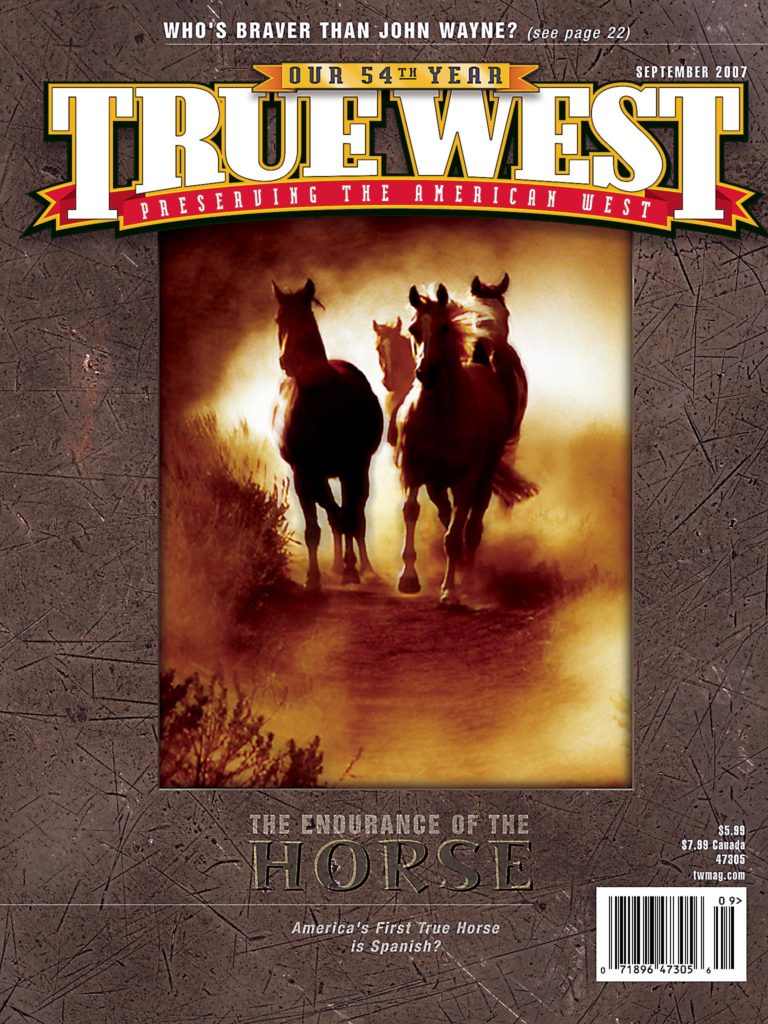

Released for the first time ever, the True West exclusive CD features 18 Romy songs from both of his Ramsey sessions and will be given away with new True West subscriptions this holiday.

“I was just born early enough to get acquainted with some of the cowboys who had worked the ranges through the 70s and 80s, to see occasional longhorns on open range,” Romy wrote in a 1967 letter to White that summed up the cowboy balladeer’s career.

“I saw big roundups and drives; saw the old backyard cow re-union commercialized into the modern rodeo; saw bands of wild horses on mountain and plain and the gradual change from the genuine Spanish mustang through the bronco era to fine quarter-horses.

“Have seen altered brands, horse thieves, blackleg, ticks, pink-eye, screw worms, bad men in high places and good men on the dodge, stampedes, range arguments, water troubles, storms, droughts, lots of bright sunshine and fair weather. Everything’s lovely and nothin’ is wrong.

“And I’m just lazy-like, lopin’ along.”

Marshall Trimble, Arizona’s official historian and vice president of the Wild West History Association, writes True West’s column Ask the Marshall. His latest book is Arizona’s Outlaws and Lawmen (History Press, 2015).