The Real Story Behind the Gun that Killed Billy the Kid

They say history is written by the victors, but sometimes it’s pawned, litigated, forgotten—and eventually sold for over $6 million at auction.

That’s the real story behind the most infamous pistol in Western lore: the one Pat Garrett used to kill Billy the Kid.

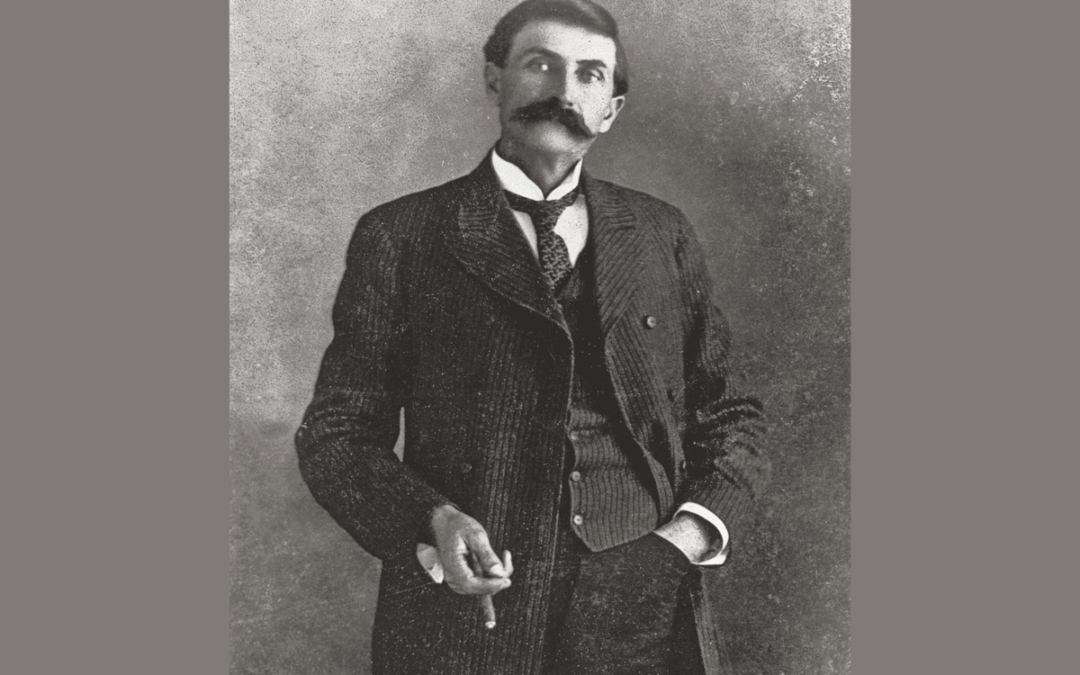

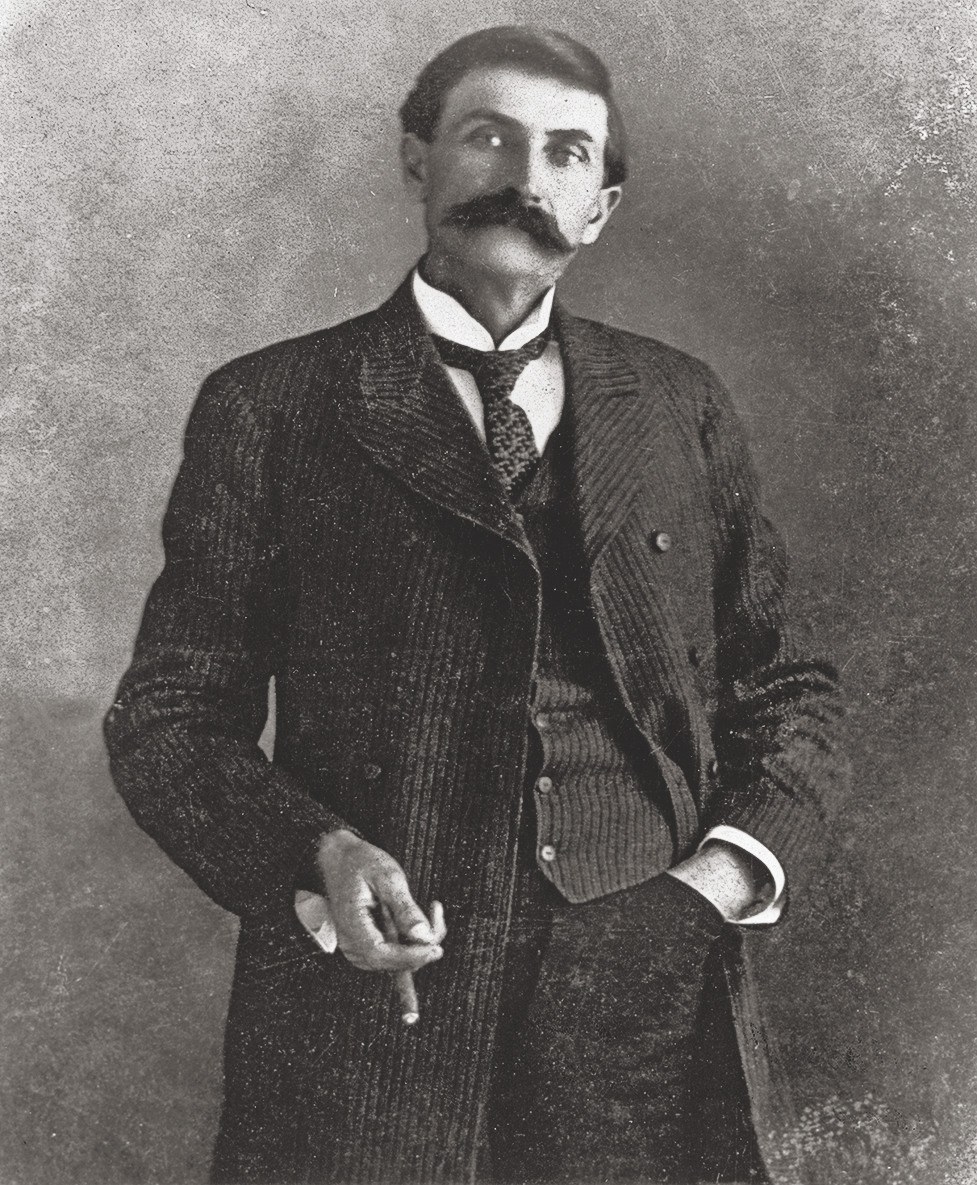

It started not in a saloon or a dusty street duel, but in a frozen standoff at Stinking Spring, New Mexico, on December 23, 1880. Garrett, newly elected sheriff and backed by Texas cowboys hired by cattleman John Chisum, had cornered Billy the Kid and his gang inside a rock house.

At dawn, the posse gunned down Charlie Bowdre, mistaking him for the Kid. With Tom Folliard already dead, the gang’s luck had run out. Billy, along with Dave Rudabaugh, Tom Pickett and Billy Wilson, surrendered after the siege. Somewhere in the aftermath, Garrett helped himself to Wilson’s Winchester rifle and Colt revolver—a common practice among lawmen of the era.

As for Billy’s own arms, they were scattered. His Winchester went to Beaver Smith, his horse to Frank Stewart, and his pistol, according to legend, was gifted to Mike Cosgrove, the brother of the mail carrier.

By the time the Kid escaped jail, killed two deputies, and fled back to Fort Sumner, Garrett still had Wilson’s pistol—a 7½-inch, .44 caliber Colt Single Action Army revolver.

On July 14, 1881, Garrett used that very gun to shoot Billy in a darkened room at Pete Maxwell’s house. One shot to the chest ended the legend in real-time—but began one of the longest-running sagas in Western history.

Fast forward 141 years: how do we know the pistol Garrett used to kill Billy the Kid is the same one that sold at Bonhams Auction in Los Angeles for $6,030,313 in 2021?

It’s all about provenance—and a bit of courtroom drama.

First, we have Garrett’s own habits. Like many lawmen, he kept souvenirs. Wilson’s revolver stayed with him for decades, until his own fortunes turned south. After being fired from a prestigious federal post—Collector of Customs in El Paso, appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt—Garrett’s life began to unravel. The final straw? Introducing his saloon-owning friend

Tom Powers as a “cattleman” during a luncheon with Roosevelt. The press had a field day. The President, feeling duped, never forgave him.

Garrett, drinking more and spending less wisely, eventually turned to Powers for money. The Colt revolver was either put up as collateral, loaned or sold outright to Powers, who displayed it in his Coney Island Saloon in El Paso.

Here’s where the tale takes a twist worthy of pulp fiction. In 1915, reporter Walter Noble Burns, covering the Pancho Villa raid in Columbus, New Mexico, visited the Coney Island Saloon. He asked about the old pistol behind the bar. The bartender casually said it was the gun that killed Billy the Kid.

Burns published The Saga of Billy the Kid in 1924—and suddenly, the Kid was back on the map. Garrett’s gun wasn’t just a relic; it was a legend.

By 1930, Powers—now rich but ailing from cancer—shot himself in the heart. Amazingly, he survived for three months before dying in 1931.

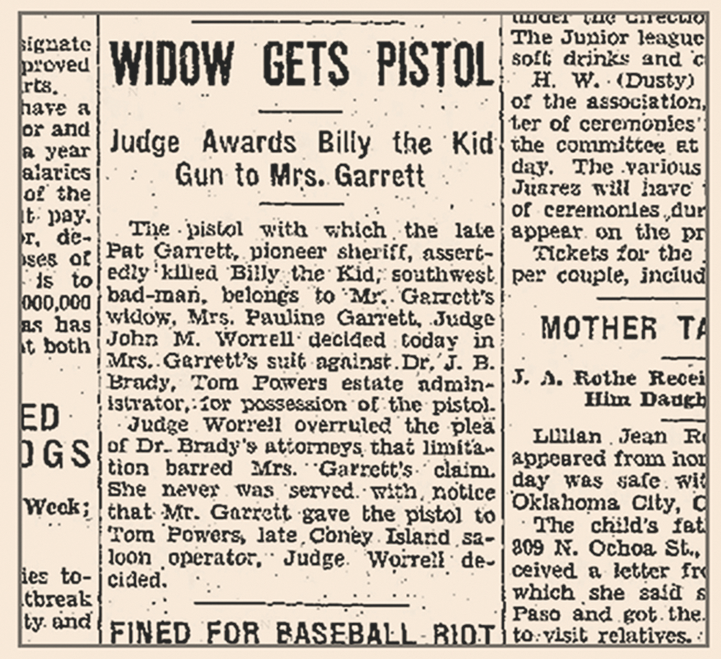

Then came the lawsuit. Apolinaria Garrett, Pat’s widow, sued the Powers estate to get the pistol back. Powers’ heirs claimed it had been payment for a loan. The case dragged on until the Texas Supreme Court ruled in Apolinaria’s favor on October 7, 1934, noting her husband couldn’t legally transfer the pistol without her consent.

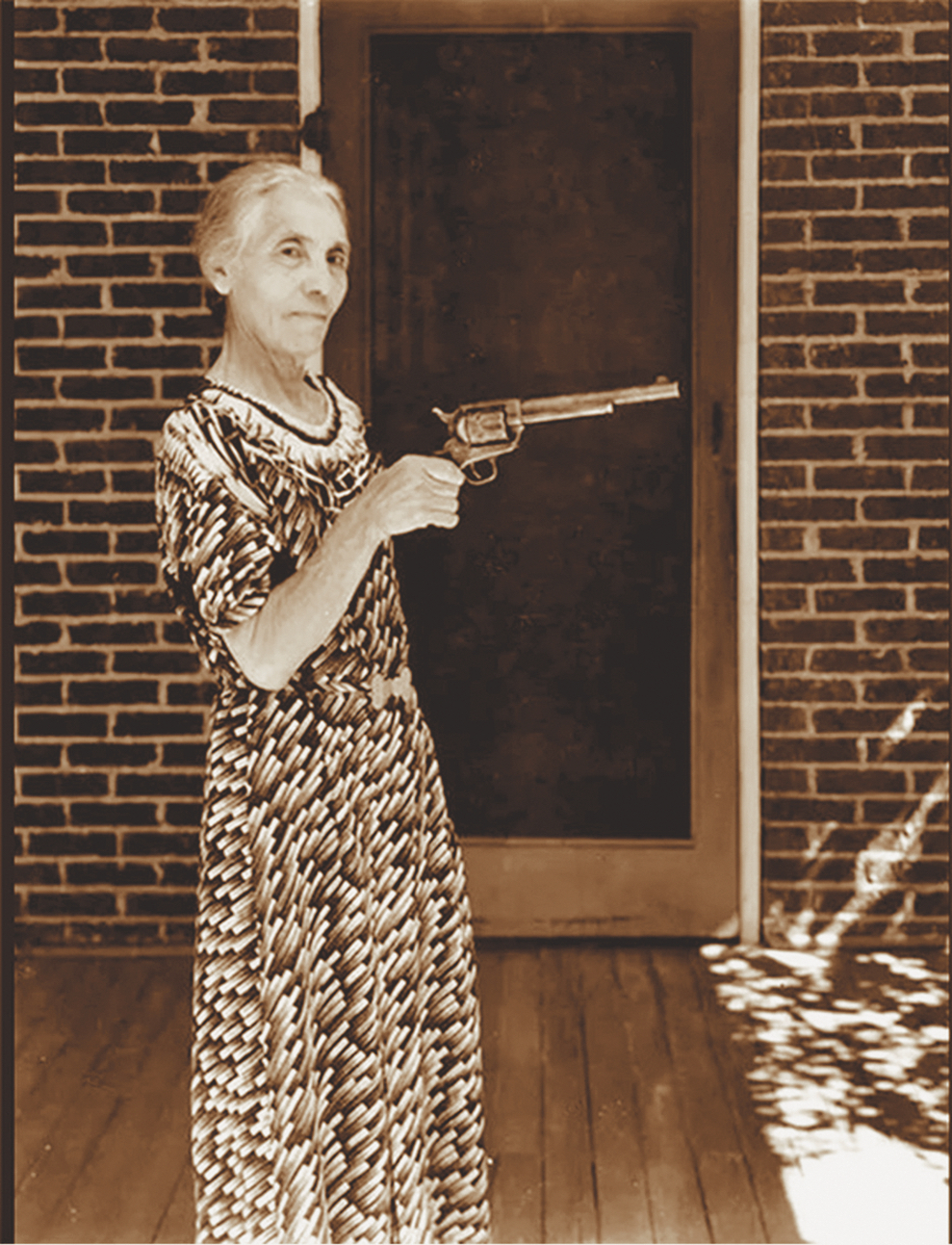

She posed with the revolver on her front porch in Las Cruces, comforted by a friend’s remark that it could be worth as much as $500.

Two weeks later, after serving as grand marshal in the Roswell parade, she died.

The Colt stayed in the Garrett family until 1983, when it was sold by Jarvis Garrett to a private collector. Eventually, it ended up in the hands of Jim and Theresa Earle of College Station, Texas—also owners of the Wilson Winchester rifle.

Upon Jim’s passing, his daughters placed both firearms up for auction. On August 27, 2021, history was made: Garrett’s Colt hammered for over $6 million, setting a world record for the sale of a firearm.

That part is still a mystery. The buyer, bidding by phone, requested anonymity.

But those in Western history circles have their suspicions. One name consistently surfaces—a high-profile collector known to own the only confirmed photo of Billy the Kid (another multimillion-dollar artifact). If he now owns both the photo and the gun, the collection becomes not just iconic, but unmatched.

And, yes, we hope it’s him. Because in a world flooded with counterfeit “Billy the Kid” pistols, this one stands tall—backed by history, paper trails and a curious little bartender’s story more than a century ago.

Garrett may have killed Billy with a single bullet, but it took a posse of decades, lawsuits, barroom storytellers, reporters and collectors to bring the full truth of that shot to light. And while the Kid didn’t live long enough to cash in on his notoriety, the gun that ended his life did—with a million-dollar muzzle flash heard round the world.