Some outlaws had their lives glorified on the silver screen. Others are mere footnotes in history. A few years ago I wrote a story about an outlaw named Bill Smith and shortly thereafter received a letter from one of his descendants thanking me for keeping memory of him alive. It wasn’t too long ago that folks tried to disassociate themselves from outlaws in the family. Now days they point with pride to some old rascal of an ancestor in the family that a century ago was shunned by his relatives.

The Bill Smith Gang was one of the wildest bands of desperadoes who ever rode those outlaw trails of Arizona and New Mexico. Maybe Hollywood wasn’t interested in an outlaw named Smith when they had names like Ringo, Hardin, Bonney and Jesse James to choose from. Smith and his wild bunch would have been a match for any of them.

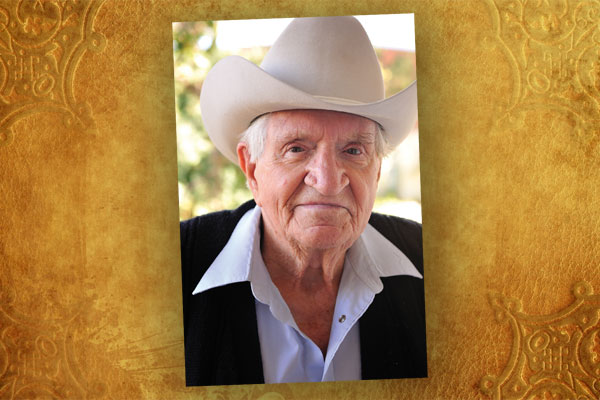

Captain Burt Mossman, of the Arizona Rangers, knew Smith about as well as anyone and according to him the outlaw chieftain had once been an honest cowpuncher who’d gone bad. According to Cap Mossman, nobody seemed to know why Smith turned his back on the law. Something he didn’t spurn, as we shall see, was the chivalrous cowboy code of honor. He stood about six feet tall with a slender, muscular frame with dark eyes and thick, course hair. The only flaw in his handsome features was a gap between his two front teeth. He was described as the kind of man who would arouse the interest of a “romantically inclined maiden.” He was about thirty-five years old when he decided to turn outlaw. The ex-cowpuncher gathered around him a band that included two brothers, George and Al, along with four other hard-bitten border desperados who would have followed him into the jaws of hell itself.

The story is told that Bill Smith had drifted into the Oklahoma Territory in his younger days and ridden with the Dalton Gang. He was back in Arizona by 1898. He was caught rustling cows in Navajo County and jailed in St. Johns. His younger brother Al was able to slip a pistol into the jail and one morning Bill appeared to be sleeping late when the jailer, Tom Berry brought his breakfast. Berry leaned over to awaken the outlaw and found himself looking into the receiving end of a .44 Colt. Smith locked the jailer in his own cell and slipped out the back way to a woodshed where Al had left a Winchester and some shells.

After his escape from the St. Johns jail, Bill Smith headed for New Mexico.

During the winter of 1900, the Bill Smith Gang terrorized most of southwestern New Mexico, holding up travelers, and robbing stores. The brazen outlaws raided ranches and rustled livestock in broad daylight. Their fame spread far and wide and before long they were being accused of every killing and foul deed that occurred in the territory.

Finally, in desperation the citizens of southwest New Mexico grew weary of lawful efforts to apprehend the gang and formed a vigilance committee that numbered several hundred (New Mexico didn’t have a territorial ranger force until 1905.) The man hunters were in the saddle constantly scouring the rugged country along the Arizona-New Mexico line. Persistence paid off as the relentless pressure soon drove the lawless bunch into Arizona. A new base of operations was set up in the remote Blue River country in northern Graham County where Bill, along with his younger brothers, Al and George, were staying at their mothers place. When word spread that the Smith gang was now operating in eastern Arizona, Mossman dispatched four Rangers to the White Mountain area.

In early October, members of the gang were seen around Springerville. According to informants they had robbed a Union Pacific train in Utah. On the way back to their lair on the Blue River, stole a bunch of horses from a rancher named Henry Barrett. Barrett organized a small posse and rode to Greer where they joined up with Arizona Rangers, Carlos Tafolla and Duane Hamblin. Someone had spotted the gang near Springerville, heading south and one of the Smith brothers was seen buying supplies in St. Johns.

They picked up the trail near Sheep Crossing, on the Little Colorado River and followed it over to the Black River. At Lorenzo Crosby’s ranch, they recruited three more men, Crosby, Bill and Arch Maxwell. The Maxwell brothers, from Nutrioso, were experienced trackers and had been friends with Bill Smith until he’d stolen some livestock from them.

The posse followed the rustlers south, past Big Lake and from there back to the Black River. An early winter storm had buried the White Mountains under a thick blanket of snow. On the afternoon of October 8, they heard three rifle shots. The posse headed off in the direction of the shots and found patches of blood in the snow. The trail led towards a steep gorge.

Meanwhile, in a canyon near the headwaters of the Black River, Bill Smith and his gang had made camp. The boys were busy skinning a bear one of them had shot late that afternoon when one of the bloodhounds picked up a scent and started howling. Bill climbed to the top of the rim for a look and saw riders coming. He charged back to camp and sounded the alarm.

Meanwhile, the posse men picketed their horses some distance away and moved stealthily towards the abyss. The Rangers, Tafolla and Hamblin, along with Bill Maxwell, headed out across a clearing while the other six took up positions on the edge of the rim. Barrett sized up the situation and called out for them to take cover. Hamblin dropped to the snow but the other two kept moving across the clearing.

Tafolla and Maxwell found themselves caught out in the open looking down the rifle barrels of seven desperate men not over forty feet away.

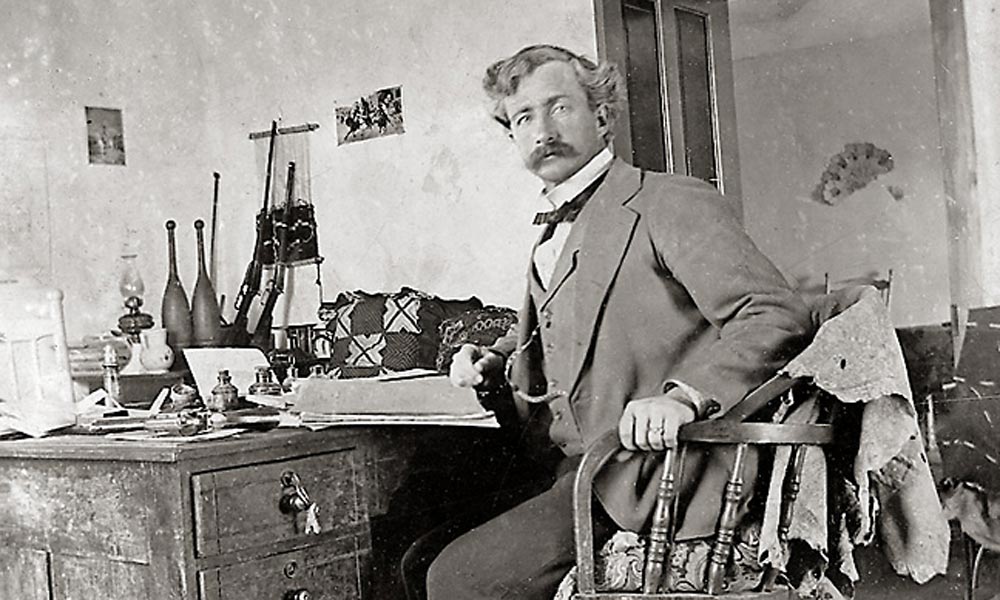

Arizona Ranger Harry Wheeler, during an interview years later with the Tucson Citizen, gave a romanticized account of the conversation between Bill Smith and the two lawmen. According to Wheeler, Maxwell and Tafolla were alone when they heard three gunshots and, going to investigate, found blood on the snow where two men had killed an animal. They followed the trail to the outlaw’s camp:

“The two parties were now within forty feet of each other, Tafolla and Maxwell standing wholly unprotected by even a shrub, two dark spots against a snowy background of white. The outlaws were invisible except where each exposed a slight portion of his arm from behind the trunk of a great tree, supporting the protruding rifle barrels which were now leveled at the two exposed men. There was silence for a few moments as the two gazed coolly and calmly into the mouths of seven guns beaded upon them. Maxwell was the first to break silence,

‘Bill Smith,’ he said, ‘we arrest you in the name of the law and the territory of Arizona, and call upon you and your companions to lay down your arms.’

“By this time standing erect, their bodies straight and motionless, their minds still cool and calm and their voices without a tremor, the utter fearlessness of the two officers, now wholly at the mercy of the outlaws, must have touched a spark of gallantry in the outlaw chief to which we have already referred. In Tafolla he had recognized a former companion of his days on the ranch, where they had worked together upon the range. Calmly he addressed his words to that officer.

‘Tafolla,’ he said, ‘we know each other pretty well, I believe. We have ridden the range together in times past in better days than these–better than any which can ever come into my life again. We have spent many an hour of weary toil and hardships upon the plains and we have enjoyed many pleasures together. I liked you then and I like you still. For your own sake, for the sake of your wife and your babies, I would spare you now. I would also spare your companion. Go your way Tafolla. Give me the benefit of one day and I will leave here and never trouble this country again. But do not try to take me, for by God! I will never be taken – neither I nor any member of my party. Your decision must be made immediately for it is getting dark.’

“There was not the slightest deviation in the tone of Tafolla’s voice from that used in demanding the surrender of the men when he made reply to the outlaw chief’s proposal. If anything he spoke more slowly and more calmly than he did in the first instance.’

“‘Bill, this friendship between you and me is a thing of the past. As for offering to spare our lives we may thank you for that and no more. For thirty days we’ve followed you, half starved and half frozen. Now we stand together or fall together. The only request I have to make of you – and I make that for old time’s sake – is that if Maxwell and I shall forfeit our lives here you will send to Captain Mossman the news and manner of our death.’

“Let him know that neither he nor the other members of the force need feel ashamed of the manner in which we laid down our lives on this spot this day. There is no more to be said; Bill, merely remember that a Ranger is speaking, and command you for the last time to surrender.’

“There was a brief fusillade of shots and all was over. The forms of Ranger Tafolla and Deputy Sheriff Maxwell lay huddled together in the snow. The men lived long enough to fight until their rifles empty, for Smith for some reason perhaps he could not have analyzed himself, evidently strove to spare the men’s lives, who so willingly died in trying to take his life. Dead shot that he was, he had placed three bullets in the hat of each man, just above the scalp, hoping, no doubt, that he would frighten the men into retreat without his having to kill them. But finding that he was dealing with men who had no fear of death, and having himself finally received a wound in his foot, he reluctantly lowered the range of his rifle.”

Harry Wheeler, last captain of the Arizona Rangers told the Tucson Citizen in 1907 he’d gathered the information from “Captain Mossman and others connected with the fight and pursuit.” Part of Wheeler’s story doesn’t jive with other accounts. It’s hard to say what really happened in those frenzied moments before the fight.

Henry Barrett’s account of the battle saw it a little differently.

According to Barrett, Maxwell called for the gang to surrender.

“All right,” Bill Smith replied. “Which way do you want us to come out?”

“Come right out this way,” Maxwell ordered.

Bill Smith walked boldly into the clearing dragging his rifle, a new .303 Savage, behind, cleverly concealing it from the lawmen.

When he was about forty feet away, Smith jumped behind a tree, quick as a flash, raised his rifle and fired a round, hitting Tafolla and the belly. His rifle blazed again, the second shot hit Maxwell in the head. The fighting became general. A furious fusillade of gunfire echoed through that snowy basin. The rest of the posse opened fire from the rim. Smith dove for cover and returned fire with his men from behind trees. Hamblin was able slip around to where the outlaws had picketed their horses. He turned loose nine saddle horses and a pack mule, leaving the gang afoot. The posse poured a withering fire down on the rustlers forcing them to retreat into the thick woods as night fell.

When the smoke lifted and the outlaws had fled, the posse moved in. Maxwell lay dead in the snow and Tafolla; hit twice in the belly lay mortally wounded, begging for water. Tafolla, game to the end kept firing his Winchester until he was out of shells. He would live in painful agony for several more hours before dying. Smith and one other outlaw had gunshot wounds. The little clearing would be known henceforth as Battle Ground.

It was said Bill Maxwell’s bullet-riddled hat lay in Battle Ground clearing for sometime afterward as the superstitious cowboys riding through the area refused to go near it.

Captain Mossman was at Solomonville when word arrived of the deaths of the two brave lawmen. He quickly organized a posse and recruited two Apache trackers. Old Josh and Chicken, from San Carlos.

The outlaws made their way to a cow camp on Beaver Creek where they learned from the cowpunchers, the identity of the other man killed in the clearing. Smith claimed to be remorseful at learning one of the men he’d killed was Bill Maxwell: “Well, I’m sure, sure sorry,” he said, “When he stood up that way we thought it was Barrett, he was the one we wanted. We feel mighty sorry over killing Bill Maxwell; he was a good friend of ours. Tell Bill’s mother for us that we’re very sorry we killed him.”

Bill Smith and his gang headed for Bear Valley; east of the Blue River they rode into Hugh McKean’s ranch at supper time and tried to buy some horses. Bill pulled out a roll of bills but McKean wouldn’t sell so they took his horses, saddles, guns and a sack of grub, at gunpoint and headed for New Mexico. Again, Smith said he was sorry he’d killed Bill Maxwell but was glad he’d killed a Ranger.

Mossman’s Apache trackers followed the trail to the McKean ranch, arriving a day after the outlaws had ridden east. Mossman and his Rangers kept up the chase until they were driven back to McKean’s ranch by another snow storm. When the weather broke, the Apaches picked up the trail again, heading towards Magdalena, New Mexico. Mossman stubbornly continued the chase all the way to the Rio Grande before losing the trail for good near Socorro.

The Arizona Rangers persistence paid off. The Bill Smith Gang was driven out of Arizona for good. Smith’s mother later told one of the Rangers that Bill and Al went to Galveston, Texas and took a boat for Argentina. Several years later George turned himself in to Graham County Sheriff, Jim Parks. The only charges against him were in Apache County so he was turned loose. He went back to live on his mother’s ranch near Harpers Mill on the Blue River.

The rest of Bill Smith’s life is a puzzle. Frazier Hunt, Mossman’s biographer said that Smith shot Ranger, Dayton Graham, in Douglas. Graham survived and later hunted down and killed the outlaw. But that seems to be a case of mistaken identity. Did Bill Smith stay in Argentina or did he return and assume a new identity? If his mother knew, she never told.

Hunt also wrote that Bill Smith later sent a letter to Mossman detailing those last brief moments in the lives of lawmen Tafolla and Maxwell. It that’s true, then despite the fact that Bill Smith turned his back on society and became one of the most ruthless desperados of his time, he maintained code of honor that bonded those men of the breed.

I couldn’t find a photo of Bill Smith. For obvious reasons he was camera-shy so I posted Arizona Ranger Captain Burt Mossman.