The Fateful Friendship of Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill

The Showman, the Chief, and the Birth of America’s Wild West Spectacle

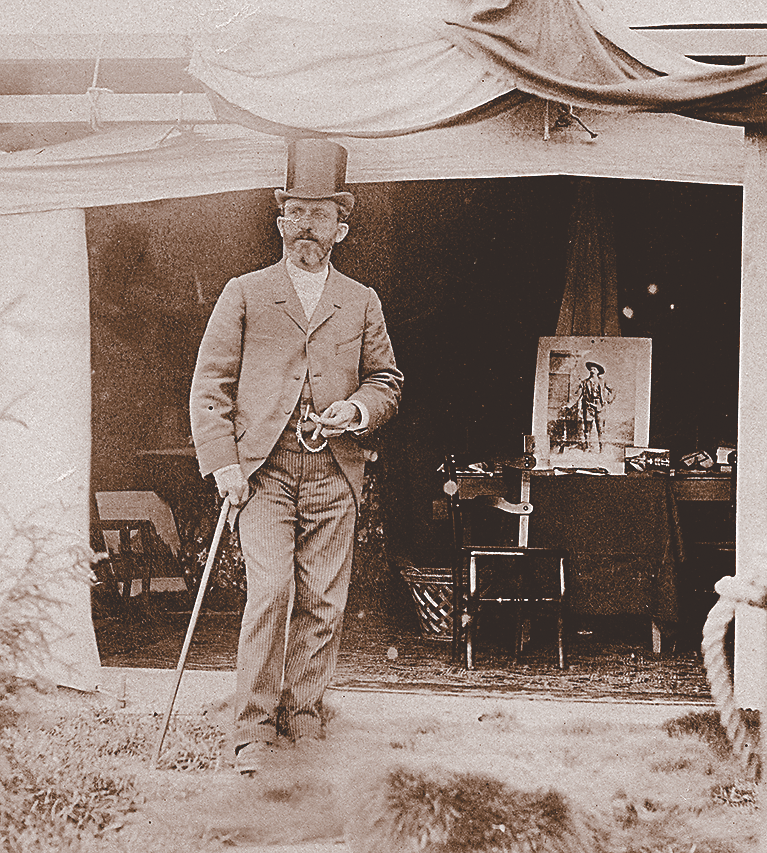

‘Near the end of the 1882 theatrical season, Buffalo Bill Cody had a fateful lunch in New York City at the restaurant adjacent to Haverly’s theater with Nate Salsbury. The conversation drifted to an idea Nate had for an arena show featuring a variety of American horsemen—cowboys, Indians and Mexican vaqueros—in daredevil feats of riding. Such a show needed a headliner and Salsbury felt Cody the perfect man for the part. Cody’s stage career had prospered, although he was growing weary of tramping the boards after 10 years and was anxious for a new challenge. Cody liked the idea and he liked Salsbury. They eventually signed a contract to establish “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West—America’s National Entertainment,” and Nate began to organize the 1884 season.

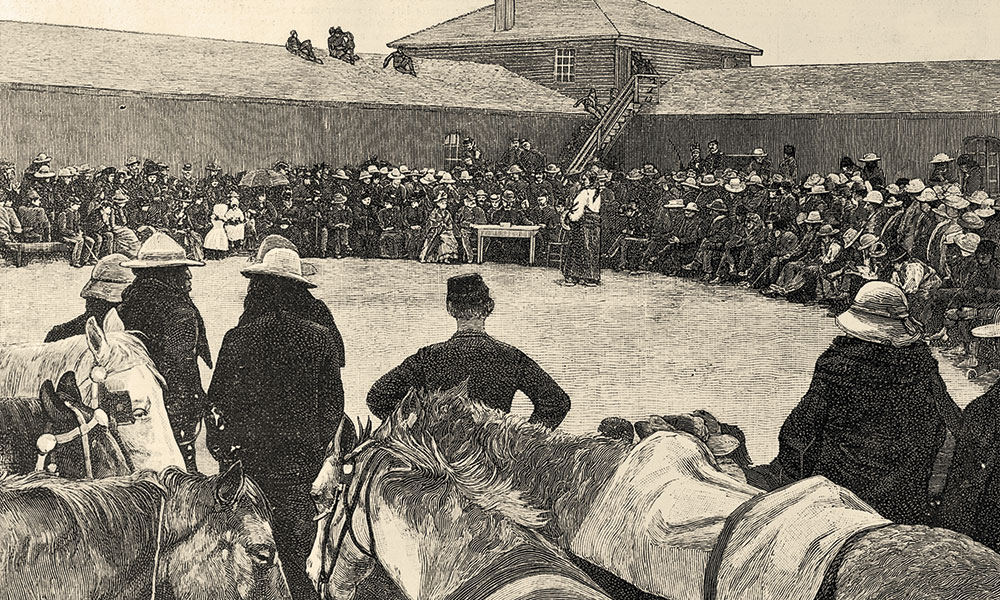

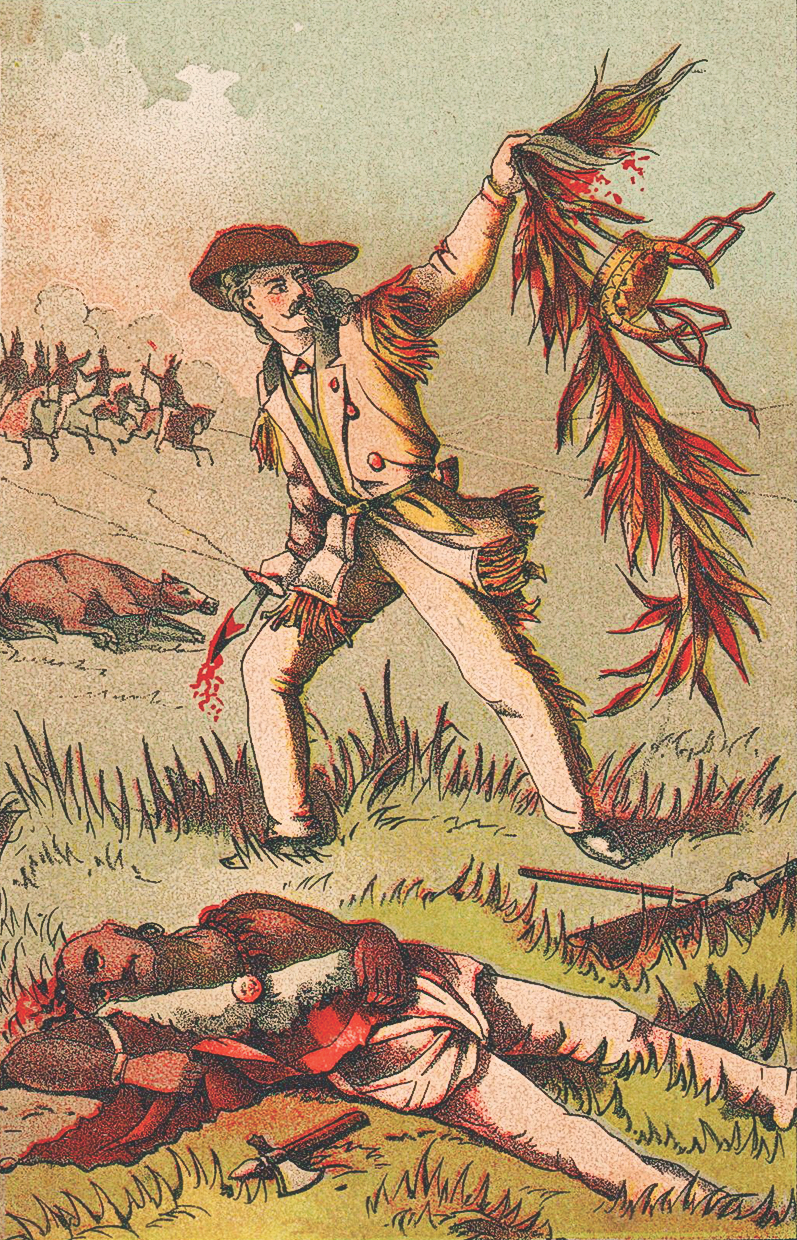

In Nate’s mind Cody would be the star attraction of the Wild West, which he saw as his invention. But Cody took an active role in management and, even more importantly, in the conception of the show. He saw it as a combination rodeo, outdoor spectacle and historical pageant. Combined with steer roping, bronc riding and Western animals including a small herd of buffalo, were historical motifs such as the Deadwood Stage, attack on the settler’s cabin, the Pony Express, Summit Springs, the first scalp for Custer, and even Custer’s Last Stand.

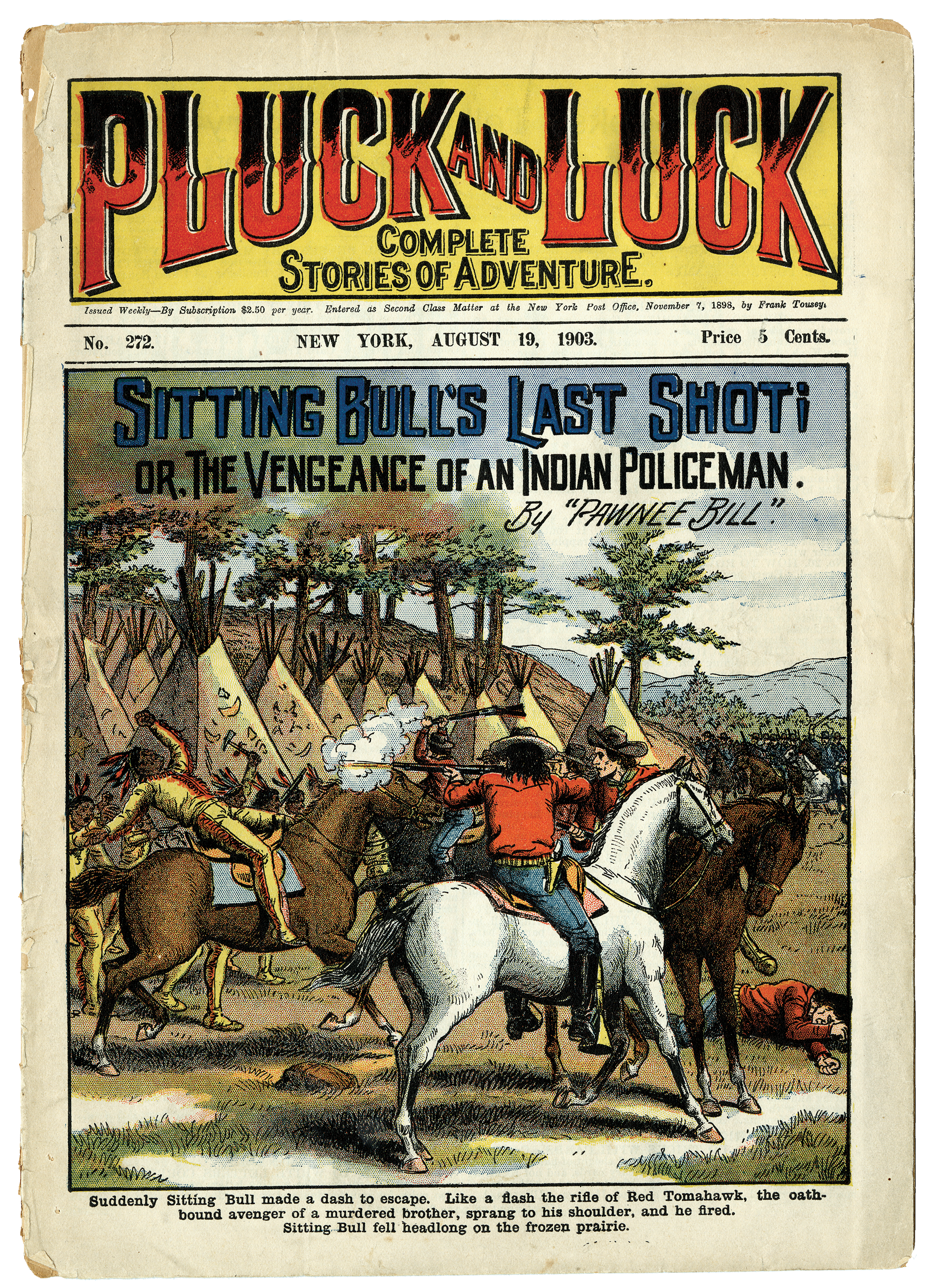

Frontier celebrities, both real and invented, were featured over the years—Frank North, A.H. Bogardus, Dr. Frank “White Beaver” Powell, Pawnee Bill, Lillian Smith, Johnny Baker, Antonio Esquivel, and most importantly, sharpshooting Annie Oakley (Phoebe Ann Moses) who signed on in 1885.

One unique celebrity who Cody was determined to sign was Sitting Bull. “I am going to try hard to get old Sitting Bull,” Cody had written in 1883. “If I can manage to get him our everlasting fortune is made.”

After the Little Bighorn battle, Sitting Bull, hounded by troops under Colonel Nelson “Bear Coat” Miles, had led his people across the “Medicine Line” into Canada. At that time war correspondent John Finerty had written of him: “He has, at least, the magic sway of a Mohammed over the rude war tribes that engirdle him. Everybody talks of Sitting Bull, and, whether he be a figure-head, or an idea, or an incomprehensible mystery, his present influence is undoubted. His very name is potent.”

Potent indeed. When he led his starving people south to surrender at Fort Buford in July 1881 everyone wanted a piece of Sitting Bull. The army had first claim on him. Although promised that if he would surrender he and his people were to be settled at Standing Rock Agency on the Missouri River with those of his people who had surrendered earlier, the army reneged. He and his 167 followers were loaded onto the steamer General Sherman and taken to Fort Randall as prisoners of war. After 20 months, in May 1883, they were finally allowed to go to Standing Rock, where they pitched their tepees near Fort Yates. A year later Sitting Bull was allowed to move south to the Grand River where he, his relatives and close adherents built log cabins.

The Indian agent at Standing Rock was 41-year old James McLaughlin, a 12-year veteran of the Indian Bureau. A somewhat unique figure in the Indian service, he was neither corrupt or a political hack, and unlike most agents, was genuinely committed, in his paternalistic way, to the well-being of his Native charges. His Dakota wife gave him insights into tribal politics that helped to make him a superior agent. He was reasonably secure in his position thanks to the support of the Catholic Church and the humanitarian reformers of the Indian Rights Association. He was also arrogant and condescending with an authoritarian streak. He began to clash with Sitting Bull, who could be equally arrogant and stubborn, almost at once. Most of the Standing Rock Sioux looked to Sitting Bull as their chief and remained loyal to him. This worried McLaughlin, who worked to raise others to power, most notably Gall, the Hunkpapa war chief who had played a leading role at Little Bighorn

“Sitting Bull is an Indian of very mediocre ability, rather dull, and much the inferior of Gall and others of his lieutenants in intelligence,” McLaughlin declared. “He is pompous, vain, boastful, and considers himself a very important personage.”

Despite the agent’s opinion, other people also considered the chief “a very important personage.” When Bismarck was selected as the capital of Dakota Territory in September 1883, McLaughlin agreed to bring Sitting Bull to ride in the procession that included former President Grant, Henry Villard of the Northern Pacific Railroad, and Territorial Governor Nehemiah Ordway. While in Bismarck Sitting Bull also discovered the people would pay two dollars for his autograph.

John Burke was soon at Standing Rock with an attractive financial package for Sitting Bull to tour with Cody’s Wild West. McLaughlin refused, since “the late hostiles are so well disposed and are just beginning to take hold of an agricultural life.”

McLaughlin lied to Burke, for he had already agreed to allow the chief,

one of his wives, and several other

Sioux men and their wives to join Alvaren Allen’s “Sitting Bull Combination.”

To sweeten the deal Allen agreed to em-

ploy the agent’s wife and son as interpreters. They traveled to St. Paul, Phila-delphia and New York with a simple program in which the Lakotas sat around a tepee smok-ing and cooking while a lecturer entertained the audience with stories of Indian life.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs was not amused by reports of the “Sitting Bull Combination” that he read in the newspapers and demanded an explanation from McLaughlin. The agent shifted blame to others and was happy to have the enterprise ended that October and Sitting Bull safely back at Standing Rock.

Cody remained doggedly on the trail of Sitting Bull, determined to have him for the 1885 summer season. He was firmly rebuffed by Secretary of the Interior Lucius Q.C. Lamar, a former Confederate general, until he enlisted the support of General William T. Sherman.

“Sitting Bull is a humbug but has a popular fame on which he has a natural right to bank,” Sherman wrote in support of Cody. The former rebel retreated before the four-star Yankee general.

Burke was promptly off to Standing Rock to strike a deal. The sly old chief played coy, but “Arizona John” was no amateur at this business. Spying a photo of Annie Oakley in Sitting Bull’s cabin he gleefully informed the chief that she had just signed to tour with the Wild West—they would be headliners together on tour. This sealed the deal. Sitting Bull had seen Oakley perform the previous year in St. Paul and had been utterly enchanted. The star-struck chief had sent a request for a photo accompanied by $65 to her.

“This amused me, so I sent him back his money and a photograph, with my love, and a message to say I would call the following morning,” Annie recalled. “I did so, and the old man was so pleased with me, he insisted upon adopting me, and I was then and there christened ‘Watanya Cicilla,’ or ‘Little Sure Shot.’”

Sitting Bull gave his new friend a photo of himself as well as a pair of moccasins that he claimed to have worn at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. This was the beginning of a beautiful friendship, perhaps only possible in the show business.

Sitting Bull still drove a hard bargain. He was to be paid $50 a week with a two-week advance, along with the exclusive right to sell his autograph and photographs, as well as a $125 signing bonus. Five Lakota warriors were to go with him at $25 a month, as well as three women for $15 a month, and reservation interpreter William Halsey at $60. Burke also agreed to pay all round-trip travel expenses to and from Standing Rock. The Sioux entourage joined the Wild West in Buffalo, New York, on June 12, 1885. The combination of Sitting Bull, Annie Oakley and Buffalo Bill proved catnip to audiences. The season played to over a million visitors (at 25 cents for children and 50 cents for adults) and secured the financial stability and future of Cody’s show.

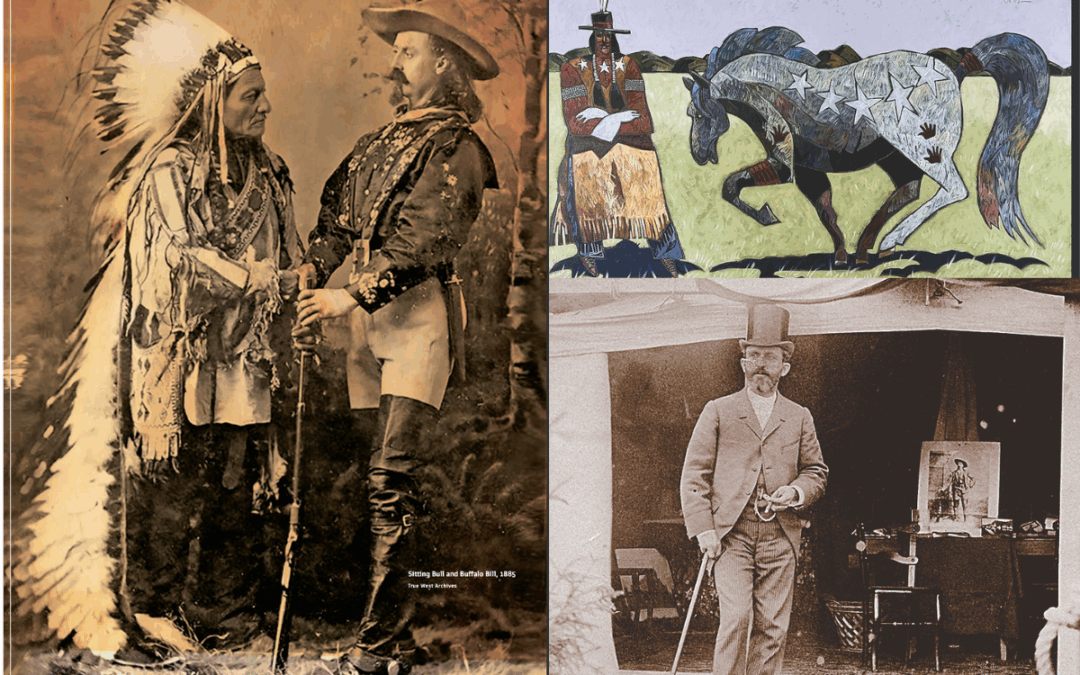

Sitting Bull was presented with great dignity in the Wild West, riding a light gray show horse in parades and in the arena, dressed in all his Lakota finery. Sometimes he was booed in the arena but that was rare “Foes in ’76, Friends in ’85” on advertising posters used a photograph taken in Montreal of Cody and Sitting Bull side by side.

Cody defended Sitting Bull in the press over the Custer battle: “The defeat of Custer was not a massacre. The Indians were being pursued by skilled fighters with orders to kill. For centuries they had been hounded from the Atlantic to the Pacific and back again. They had their wives and little ones to protect and they were fighting for their existence. With the end of Custer they considered that their greatest enemy had passed away. Sitting Bull was not the leader of the Sioux in that battle. He was a medicine man who played on their superstitions—their politician, their diplomat.”

The two old foes formed a bond of true friendship. It was bold of Cody to speak up so forcefully in defense of his new friend just nine years after Custer’s Last Stand. Even as he celebrated the “winning of the West” in his show, Cody came to understand all that had been lost in that great conquest.

When the Wild West played Wash-ington, Cody took Sitting Bull to the White House for a brief audience with President Grover Cleveland. The meeting was unsatisfactory for the chief. They also visited with General Phil Sheridan at army headquarters, although Sitting Bull seemed more impressed with the war paintings on the walls than with his military nemesis.

The season ended in St. Louis that October and Sitting Bull and his Lakota companions returned to Standing Rock. He had not kept much of his show money, sending most of it home to his family and giving the rest to bootblacks, beggars and street urchins. He could not understand how a land so wealthy could also have such poverty. Annie Oakley, who had grown ever closer to the old chief during their four months together noted that his money “went into the pockets of small, ragged boys. Nor could he understand how so much wealth could go brushing by, unmindful of the poor.”

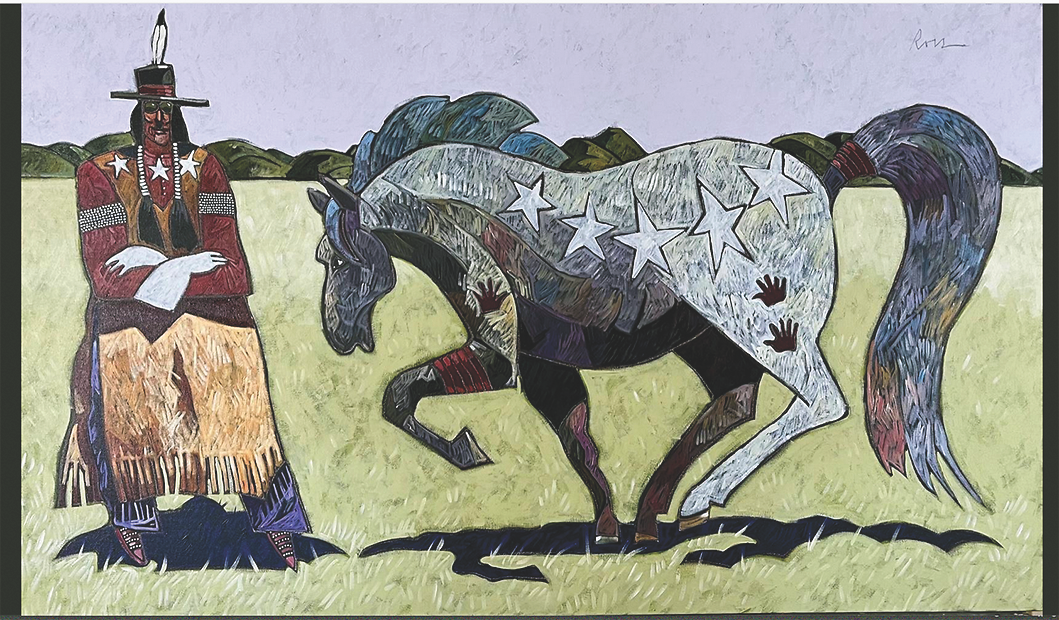

In parting Cody gave Sitting Bull a size 8 white Stetson and the gray prancing horse that he had ridden in the arena. Sitting Bull treasured both. Once when a relative dared to put on the hat he upbraided him: “My friend Long Hair gave me this hat. I value it very highly, for the hand that placed it upon my head had a friendly feeling for me.”

When John Burke returned to Standing Rock to recruit Sitting Bull for another season with the Wild West he found McLaughlin intractable. The agent felt that the previous season with Cody had only added to the chief’s arrogant self-importance.

“He is inflated with the public attention he received,” the agent declared, “and has not profited by what he has seen but tells the most astounding falsehoods to the Indians.”

McLaughlin was also irritated that Sitting Bull had “squandered” all of his show money on feasts and gifts for the Hunkpapas. This was expected of a wealthy chief by the people, but to McLaughlin “he makes no good use of the money he thus earns.” Of course, his gifts enhanced his influence over the people and undercut McLaughlin’s authority. So rather than get rid of this troublesome chief by allowing him to go out with Cody, he preferred to keep him close under his thumb to further humiliate and punish him. Sitting Bull’s show business career was over.

With Sitting Bull and Annie Oakley as headliners the Wild West grossed over a million dollars in 1885 (with $100,000 profit). Salsbury used the money wisely, hiring their own railroad cars for transport, a lighting system for nightly performances, seating and a canvas canopy, and a large Western scenic-painted background. The cast increased to 240 people, with more Indians as well as the addition of several cowgirls. The crew was organized with military precision, with crew bosses to tackle the various set-ups and break-downs.

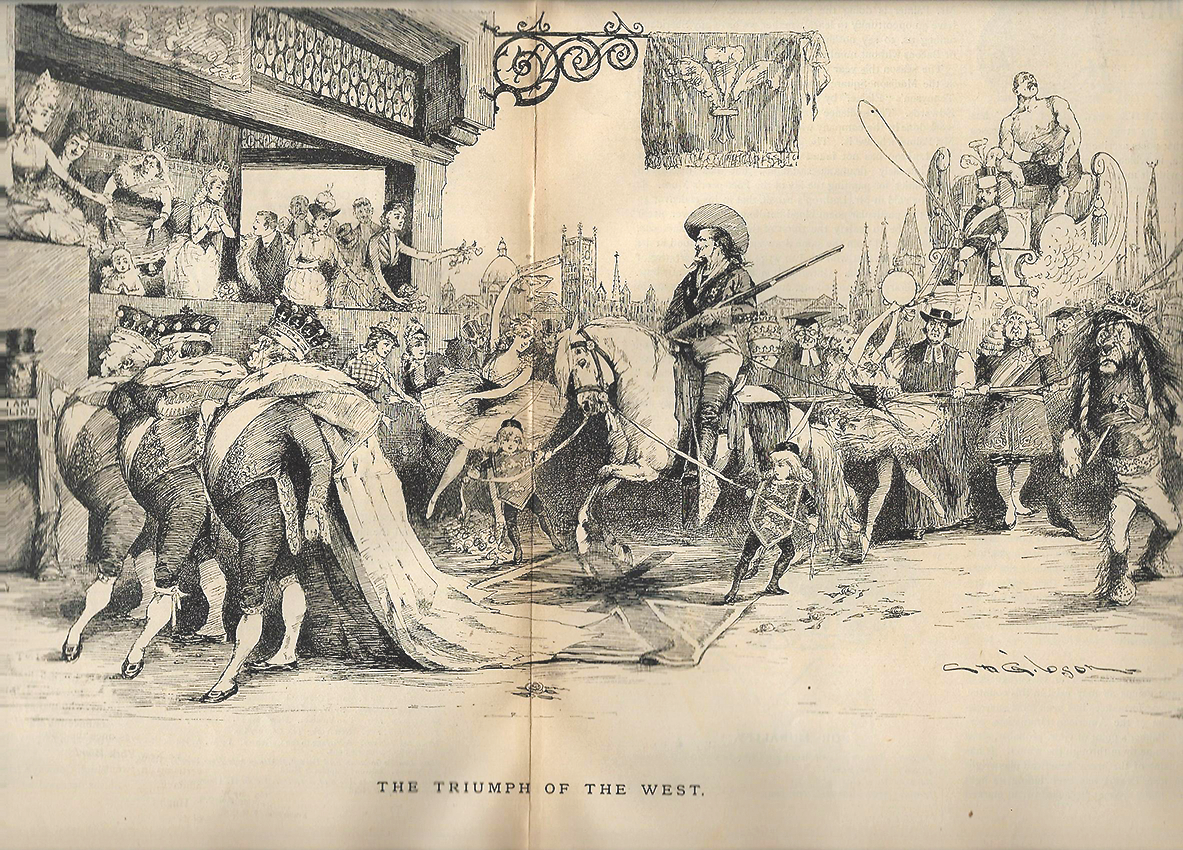

Cody and Salsbury took the Wild West to Queen Victoria’s 1887 Golden Jubilee in London, where it proved to be a sensation. Over two million people would see the show in London. Not since 1066 had the English been so easily conquered. Buffalo Bill gave them, and later other Europeans, a taste of the vanishing frontier that had so enthralled his own countrymen. He exploited the romantic possibilities of the story of the American West making them intelligible to millions who had no other knowledge of the frontier than what he presented. In turn he became a buckskin-clad goodwill ambassador, winning the hearts of Europe as had no American since Benjamin Franklin.

Queen Victoria came to Earl’s Court arena on May 11 for a command performance of the Wild West. When the American flag was presented at the top of the show the Queen rose and bowed toward it, as did her entourage. Cody and the other cast members let out a lusty American war-whoop, for this was the first time a British monarch had ever saluted the flag of the United States. Thus did a century of rivalry and resentment melt away—for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had conquered the heart of the Queen and her people as no army ever could, forging bonds of friendship that would never again be severed.

The Jubilee tour was one triumph after another as the whole country seemed to be caught up in the fascination of all things Wild West. Colonel Cody was feted everywhere (he had now adopted Colonel as his title thanks to an 1887 appointment as colonel in the Nebraska National Guard) and dined with the leaders of British society, including Lord and Lady Randolph Churchill, and their young son Winston.

“He was probably the guest of more people in diverse circumstances than any man alive,” observed Annie Oakley about Cody. “Tepee and palace were all the same to him. And so were their inhabitants.”

The next year the Wild West invaded the continent of Europe with equally spectacular results—financially, diplomatically, and culturally. Salsbury planned the tour to exploit the Paris 1889 Exposition. The President of France attended the opening, as did Thomas Edison who happened to be visiting Paris at the time. French artists descended on the Wild West grounds and all things cowboy became the rage. The show moved on to Barcelona, where five cast members died of the flu, then sunny Naples, and finally Rome where the cast had an audience with Pope Leo XIII. Triumphs followed in Florence, Milan and Venice, where Cody and several Indian companions rode in a gondola. They went north into Germany where the populace became infatuated with the American West. They played in Berlin for a month to overflow crowds. “The show is simply incomparable and unrivaled,” declared a Berlin newspaper. The summer tour concluded with shows in Vienna, Dresden, Leipzig, Bonn, Coblentz, Frankfurt, ending in Stuttgart.

Several of the show Indians became ill and were sent home, which led to unfounded rumors that they had been mistreated. In response, and with the show season over, all the Indians were sent home with Burke. Cody soon followed, anxious to visit Washington and defend his treatment of his Native performers. When he landed in New York he was greeted by reporters who wanted to know what he thought of the Ghost Dance troubles among the Western tribes.

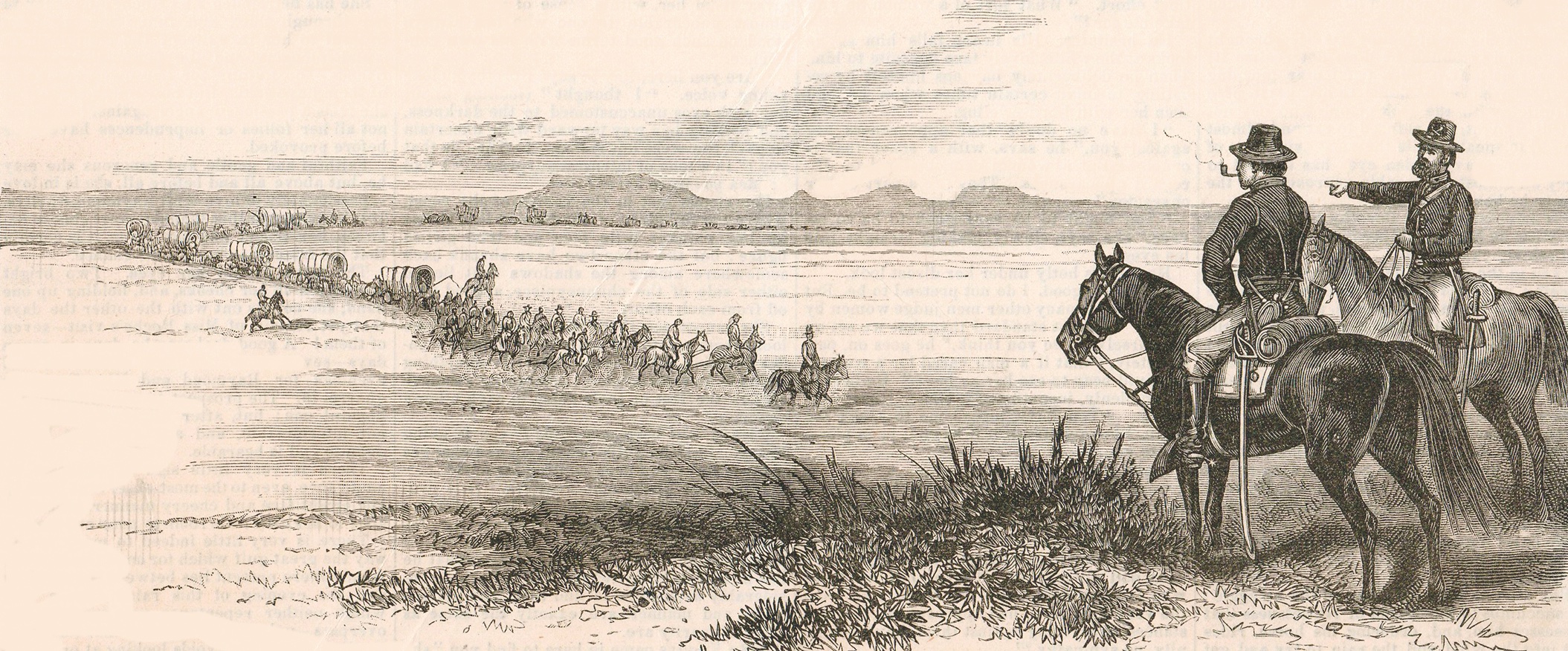

These were hard times on the Sioux reservation. New land agreements resulting from the 1887 Dawes Act had reduced the reservation by 60 million acres. The land was opened to White ranchers and homesteaders while the Sioux were encouraged to take land allotments of 160 acres which would eventually lead to citizenship. The government needed Sioux consent to this under the 1868 treaty, but when that was not forthcoming a commission was sent out led by General George Crook.

In consort with McLaughlin, the general exploited Sioux factionalism and secured the required signatures to sell the surplus land for $1.25 an acre (less after three years for unsold land). Sitting Bull opposed this without success.

“Sitting Bull tried to speak after the signing commenced, but I stopped him,” Crook wrote in his diary. “Then he tried twice to stampede the Indians away from signing, but his efforts failed, and he flattened out, his wind bag punctured, and several of his followers have deserted him.”

Events now moved swiftly. In February 1889 a statehood bill passed bringing North and South Dakota, as well as Montana and Washington, into the Union. Now the two new Dakota states would have even more political clout with the administration of President Benjamin Harrison to demand that surplus Sioux land be thrown open to settlers. At the same time, as an economy measure, the government cut the rations provided to the Indians. In the six new reservations—Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Lower Brule, Crow Creek, Rosebud, and Pine Ridge—hunger stalked the people. Influenza struck that winter with devastating results. The Lakota, now deeply divided by the Indian agents into “progressives” and “nonprogressives,” fell into deep despair.

Now came word that to the west in Nevada a Paiute holy man named Wovoka was preaching a new religion called the Ghost Dance. If the people would perform this dance the buffalo would return along with their deceased ancestors—and the white men would vanish. A Minniconjou named Kicking Bear became the Ghost Dance apostle among the Sioux and won many converts at Rosebud and Pine Ridge. Sitting Bull invited him to preach at Standing Rock, where his sermons won many converts. McLaughlin responded by ordering him off the reservation. It was too late, for now Sitting Bull’s log cabin encampment became the scene of daily dances. Sitting Bull did not dance, but he encouraged others to do so. The tepees of the dancers soon ringed Sitting Bull’s cabins. The dancers often fell into trances and saw their dead relatives. More people began to dance. Sitting Bull once again assumed a leadership role, which further troubled McLaughlin.

McLaughlin remained calm, but the other reservation agents became increasingly hysterical over the Ghost Dance, as did nearby settlers. They called for the army to send in troops to disperse the dancers. On November 20, 1890, troops moved to occupy Pine Ridge and Rosebud agencies with orders to arrest the leaders of the Ghost Dance.

General Nelson A. Miles, son-in-law of General Sherman and the most experienced Indian fighter in the army, now commanding the Division of the Missouri, deluded himself into believing that the Ghost Dance was the greatest crisis since Little Bighorn.

“It was a threatened uprising of colossal proportions,” he wrote, “extending over a far greater territory than did the confederation inaugurated by the Prophet and led by Tecumseh, or the conspiracy of Pontiac, and only the prompt action of the military prevented its execution.”

Cody had just returned from Europe when he received a telegram from Miles asking him to hurry to his Chicago headquarters. He had hoped to join Burke in Washington to answer the complaints from the hacks in the Indian Bureau over false claims of mistreatment of the show Indians, but instead headed to Chicago from New York. He found Miles fretting over a possible war with the Ghost Dancers.

“He asked me if I could go immediately to Standing Rock and Fort Yates, and thence to Sitting Bull’s camp,” Cody recalled. “He knew that I was an old friend of the chief and he believed that if any one could induce the old fox to abandon his plans for a general war, I could.”

Miles wrote out an order on November 24, 1890, marked “confidential” for Cody to “secure the person of Sitting Bull” and deliver him to the nearest military post. Miles hoped to remove the chief from the scene of turmoil and perhaps bring him to Chicago for a meeting. He also handed Cody his card with orders for army officers to assist him scrawled in pencil on the back.

Cody promptly departed for Fort Yates accompanied by show associates Pony Bob Haslam and Frank “White Beaver” Powell, who had been particular friends with Sitting Bull during his season with the Wild West. This colorful entourage arrived at the Dakota fort on November 28. Cody presented his orders as well as General Miles’ calling card to Lieutenant Colonel William F. Drum, the post commander. Drum, who was working closely with the devious McLaughlin, was mortified by these orders. He hurriedly got word off to McLaughlin while he had his officers entertain Cody at the post officers club. The plan was to get him roaring drunk and delay his journey to Standing Rock until McLaughlin could wire the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and have the mission cancelled. They misjudged their man.

“Colonel Cody’s capacity was such that it took practically all the officers in details two or three at a time to keep him interested and busy through the day,” noted the post surgeon.

The officers fell by the wayside as Cody closed down the club and retired in good spirits. The next morning he slept in but was still on the road well before noon. He loaded a buckboard with gifts for Sitting Bull and his family, with an emphasis on candy as he knew the chief had a notorious sweet tooth, and was off on his mission to the Grand River camp.

The increasingly frantic McLaughlin now sent his agency interpreter out to intercept Cody with a false story that Sitting Bull was on his way into the agency by another road. He anxiously awaited a response to his telegram to Washington.

“William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) has arrived here with commission from Gen. Miles to arrest Sitting Bull,” he had written. “Such a step at present is unnecessary and unwise, as it will precipitate a fight which cannot be averted…Request Gen. Miles order to Cody be rescinded and request immediate answer.”

This was a tissue of lies, for Cody and his unarmed party were in no danger. Cody was not about to force an arrest. It was not in his power to do so even if he had wished to—and he did not. A Chicago newspaperman had been in Sitting Bull’s camp the day before taking photographs of Ghost Dancers without any problem. There was no danger.

“If they had left Cody alone, he’d have captured Sitting Bull with an all-day sucker,” noted Buffalo Bill’s cowboy star Johnny Baker.

The Secretary of the Interior hurried to President Harrison with McLaughlin’s telegram and the president promptly recalled Cody. The recall order reached Cody’s party just before they reached Grand River. Cody said that Harrison later admitted to him that his recall was in error and apologized. Well he should, for that order set a great tragedy in motion.

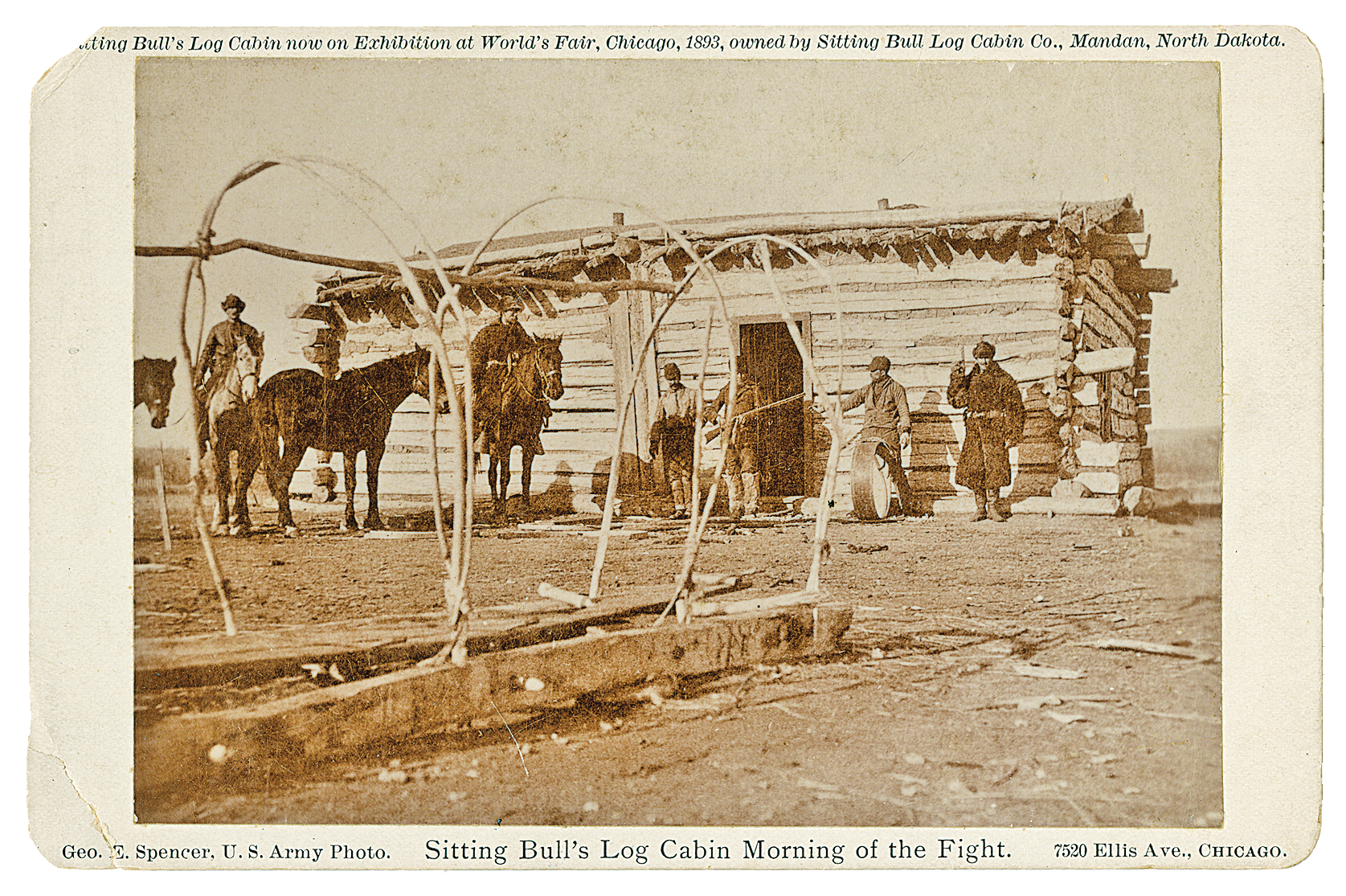

McLaughlin was now determined to arrest Sitting Bull with his Indian police. Colonel Drum agreed to cooperate. He would have two companies of cavalry nearby to assist the Indian police if necessary. On December 15 Captain Bull Head, who had fought with Sitting Bull at Little Bighorn and Rosebud, was to lead 44 Sioux policemen to arrest the great chief. As he made his plan he instructed Red Bear and White Bird to go to Sitting Bull’s corral and saddle the gray show horse in readiness for the arrest. A little before six that morning, under cloudy skies and an icy drizzle, they reached the Grand River village.

Sitting Bull was asleep in one of his two cabins with his wife and 14-year-old son Crow Foot, a small child, and three guests. The rest of his family were in his smaller cabin to the north. They were awakened by barking dogs and a sudden pounding on the cabin door.

The door flew open and dark forms rushed in. A candle was lit.

“Brother, we came after you,” announ-ced Sergeant Shave Head.

“How, all right,” the surprised chief answered as he was seized and drug from under his blankets.

He was naked and demanded to be allowed to dress. The police complied but hurried him along pushing him toward the door. Sitting Bull’s wife began to upbraid the police and then to wail.

Bull Head and Shave Head pushed Sitting Bull through the door and out into the darkness beyond. Sergeant Red Tomahawk walked behind, his pistol in the chief’s back. The gray horse waited, saddled and ready.

The barking dogs had alerted the village and a great crowd now gathered. Angry people shook their fists, some waved rifles. “You shall not take our chief!” went up the cry.

From the doorway Crow Foot called after his father: “You always called yourself a brave chief. Now you are allowing yourself to be taken by the ceska maza [metal breasts-badges].”

“Then I shall not go,” Sitting Bull declared.

Sitting Bull’s friend Catch-the-Bear took aim with his rifle and shot Bull Head. As he fell the policeman shot Sitting Bull in the chest. At the same moment Red Tomahawk fired into the back of the chief’s head. Shave Head went down at the same time, shot in the stomach, while policeman Lone Man killed Catch-the-Bear.

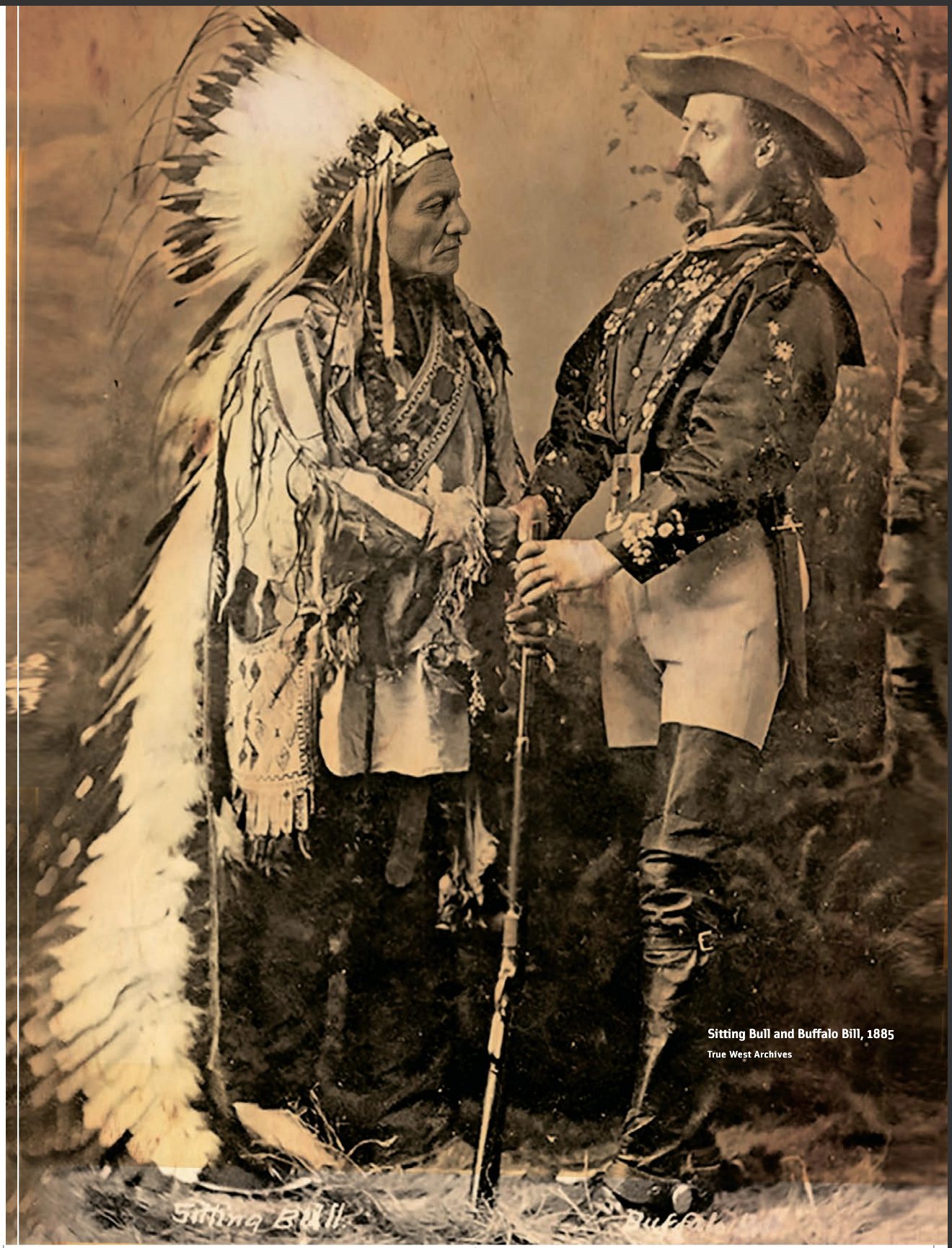

Suddenly the gray horse, trained to perform amidst gunfire, began to prance, it was as if Sitting Bull’s spirit had entered his body. In the dim dawn light, amid the haze of black powder smoke, the horse appeared as if an apparition. He danced around the bloodied body of the great chieftain who had been his master. He danced above the old warriors who had fought beside Sitting Bull on the Yellowstone, at Rosebud, and against Long Hair Custer on the Little Bighorn, all killed now, dead by the hands of their own people. Then the horse sat down on his haunches, raised his hoofs in the air—was it perhaps a prayer of solace for all that was now lost, for the death of the great chief marked the end of the old ways forever? This was indeed a ghost dance. There was a momentary halt in the shooting as all stared in awe at the mystical horse.

Some of the police retreated into the cabin, while others took cover behind it and in the corral. Now they all began to fire again. The Ghost Dancers took cover in nearby timber leaving six of their number dead. The spirit horse stood his ground, untouched by the hail of bullets. As the police pulled their wounded comrades into the cabin they discovered Crow Foot. They asked the mortally wounded Bull Head what to do with the boy.

“Kill him; they have killed me,” he snarled.

Red Tomahawk smashed him across the head with his rifle butt as two other policemen shot him. Red Tomahawk called Hawk Man to his side and ordered him to mount the gray horse and ride to get help from the soldiers. Amid a hail of bullets, he galloped away, but the magic of the gray horse kept him untouched.

At dawn the cavalry arrived and quickly drove Sitting Bull’s people away. Captain Edmond Fechet reported that he “saw evidence of a most desperate encounter” with the bodies of eight dead Indians, including Sitting Bull, in front of the cabin along with two dead horses. Inside the cabin he found four dead policemen and three wounded men, two mortally. He was anxious to depart, a bit unnerved by the constant wails of the women.

Fechet commandeered a nearby wagon and ordered Sitting Bull’s body placed in it. Someone had smashed in the chief’s face, and he looked particularly gruesome as they tossed him into the wagon. The dead Indian policemen were placed on top of him, and the wagon, soldiers, and Indian police rode north up the trail to Standing Rock.

They took Sitting Bull’s mangled corpse to Fort Yates where on December 17 he was buried in the post cemetery. McLaughlin and three army officers supervised the burial. Wrapped in canvas the body was placed in a crude wooden coffin that was too small. The soldiers had to sit on the lid to close it. They lowered him into a pauper’s grave and poured lime on top before shoveling in dirt.

“We laid the noble Old Chief away without a hymn or a prayer or a sprinkle of earth. Quicklime was used instead,” recalled J.F. Waggoner, the soldier who had made the coffin. “It made me angry. I had always admired the Chief for his courage and his generalship. He was a man!”

Cody, furious when news of the death of the great chief reached him in Chicago, told a reporter for the Chicago Tribune that it “was a cold-blooded murder.” Other newspapers echoed this accusation. The Chicago Herald reported that sources at Standing Rock confirmed “a quiet understanding between the officers of the Indian and military departments that it would be impossible to bring Sitting Bull to Standing Rock alive…There was, therefore, a complete understanding from the commanding officer and the Indian Police that the slightest attempt to rescue the old medicine man should be a signal to send Sitting Bull to the happy hunting ground.” Public outrage, especially in the East, led to talk of a congressional investigation but nothing came of it. The House of Representatives decided it was best to leave the matter alone.

Sitting Bull’s death panicked the Ghost Dancers. Hundreds of Hunkpapas fled south to the Cheyenne River Reservation, while some pushed even further south to the Ghost Dance stronghold at Pine Ridge. Big Foot, the leader of the Minneconjous at Cheyenne River, under pressure from his more militant head men, bolted for Pine Ridge with over 300 people, including 48 of the Hunkpapa refugees. Troops, including Custer’s old regiment the 7th Cavalry, were soon in hot pursuit.

Orders from General Miles, now in the Black Hills, were clear. Big Foot’s band must be stopped: “Find his trail and follow, or find his hiding place and capture him. If he fights, destroy him.”

Major Samuel Whiteside, with four companies of the 7th and a battery of two Hotchkiss guns, intercepted Big Foot’s band on Porcupine Creek where the chief, near death from pneumonia, surrendered his 120 men and 230 women and children. Whiteside sent a message to Colonel James Forsyth, who commanded the 7th, to bring up the rest of the regiment to the trading post on Wounded Knee Creek to facilitate the disarming of the Indians. Whiteside had noticed marked hostility among Big Foot’s young men, and hoped this show of force might overawe them. Forsyth, who now took command at Wounded Knee, had over 500 men and two batteries of Hotchkiss breech-loading mountain artillery.

On the morning of December 29, 1890, Forsyth dispersed his troops, with the Hotchkiss guns on a hill above Big Foot’s village and moved in to disarm the Indians. The Sioux surrendered only a few old guns, so it was decided to search the village. Forsyth ordered the assembled warriors to remove their blankets where he thought their Winchesters were concealed.

A Ghost Dance leader named Yellow Bird, who had been dancing and singing the whole time, suddenly tossed two handfuls of dirt into the air. Several young men threw off their blankets and leveled their rifles at the soldiers. Both sides opened fire at point blank range. Among the first to fall was Big Foot. Within five minutes twenty warriors and thirty soldiers were dead or wounded on the ground. As the Indians broke through the soldier line, Forsyth raced up the hill to the artillery and gave the order to fire. The officers at the guns had hesitated for fear of hitting their own men but now opened up. When it was over at least 153 Sioux—many of them women and children—were dead and 44 wounded, along with 25 soldiers killed and another 39 wounded. It had been a perfect slaughter with large numbers of women and children, as well as several soldiers, indiscriminately cut down by the Hotchkiss guns. General Miles termed it “a massacre.”

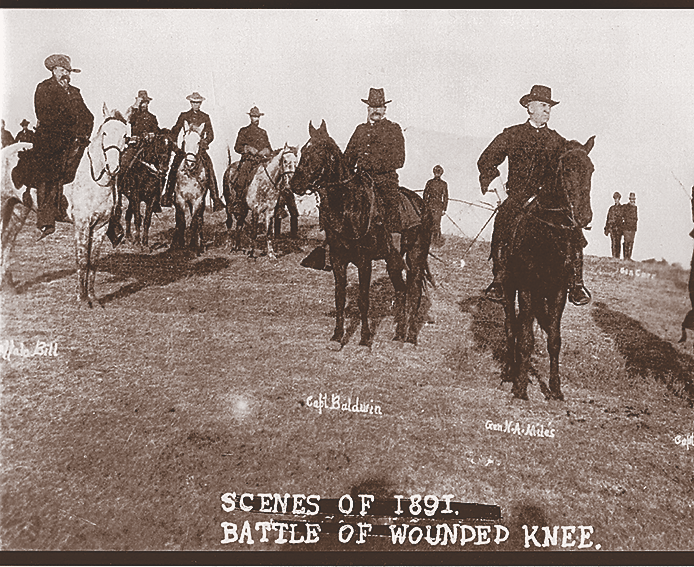

The campaign, the last of nearly four hundred years of conflict since Columbus first landed, came to its sad end. Buffalo Bill Cody was there, promoted from colonel to general in the Nebraska National Guard, and sent by the state governor to confer with Miles. He reported all quiet on Pine Ridge and urged respect for Indian rights: “I think it looks like peace, and if so, the greater the victory.” Many of his show Indians were employed as police at Pine Ridge and he fretted over their safety. He also worried about the Ghost Dancers, and when Miles sent 19 as prisoners to Fort Sheridan at Chicago, Cody interceded and had them released to his custody to accompany the Wild West to Europe in the spring.

It all came to a colorful but melancholy end on January 21 in a grand review of over three thousand soldiers at Pine Ridge. Cody sat his horse next to General Miles as the troops passed in review amidst a blinding sandstorm. Guidons whipped in the wind as one by one the regiments passed in review. As Whiteside led the 7th in review the band struck up “Garryowen,” Custer’s regimental air, and Miles, overcome with emotion, removed his hat in a quiet salute.

Cody had one last mission to undertake. He sought out the family of Sitting Bull to ask if he might purchase the chief’s gray horse from them. They agreed. And so the dancing horse returned to the Wild West.