A strange and heartbreaking moment transpired outside Sitting Bull’s cabin in 1890, while he was being assassinated during an attempted arrest at Standing Rock Reservation.

At the sound of gunfire, a horse tethered to a railing started to “dance,” trained to do so while he was in the Wild West, “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s famous spectacle of which Sitting Bull was a part for four months during 1885. Cody had presented the horse to the Lakota holy man when he left the show to go home.

The image haunted me for a long time, and I called Chief Arvol Looking-Horse, 19th-generation keeper of the sacred white buffalo pipe for the Lakotas, to seek his views on the matter. “It was the horse taking the bullets,” he said. “That’s what they did.”

On November 24, 1890, Cody had received a telegram from Gen. Nelson Miles asking him to proceed to Standing Rock, where a tense situation was unfolding. Miles authorized Cody “to secure the person of Sitting Bull, and deliver him to the nearest Commanding Officer of US Troops.”

The general hoped Cody could convince his friend to surrender—for the last time. The holy man had made enemies as the last roadblock in establishing the Great Sioux Reservation. Even though Sitting Bull never signed, the Dawes Act became federal law.

On Thanksgiving, Cody arrived in Mandan, North Dakota, with Lt. G.W. Chadwick and two cast members, Dr. Frank “White Beaver” Powell and former Pony Express rider “Pony Bob” Haslam. They planned to go to Standing Rock the following day.

Then Cody received a telegram. His ornate, three-story house in North Platte, Nebraska, was on fire. Friends and neighbors were trying to save it with a bucket brigade. “Save Rosa Bonheur’s painting,” he wrote back. “The rest can go to blazes.”

The house was destroyed, but not that famous portrait of Cody that Bonheur had painted when the Wild West was in Paris, France. Even as his wife and daughter were trying to save his home, Cody’s friendship with Sitting Bull came first.

Yet when Cody reached Fort Yates on the reservation, he was drunk. Powell and Haslam later learned that Agent James McLaughlin’s officers had plied the showman with liquor to prevent him from heading to Sitting Bull’s cabin. The fact that his beloved home on the Platte was aflame may have contributed to his urge to knock himself out.

The next morning, sobered up, Cody left to see Sitting Bull. Joseph Primeau, McLaughlin’s interpreter, told Cody’s party that Sitting Bull was not home, but headed to Fort Yates, on another trail. Cody changed course.

As he camped along Four Mile Creek, Cody received the news that President Benjamin Harrison had rescinded the order for Cody to bring in Sitting Bull. Cody left town.

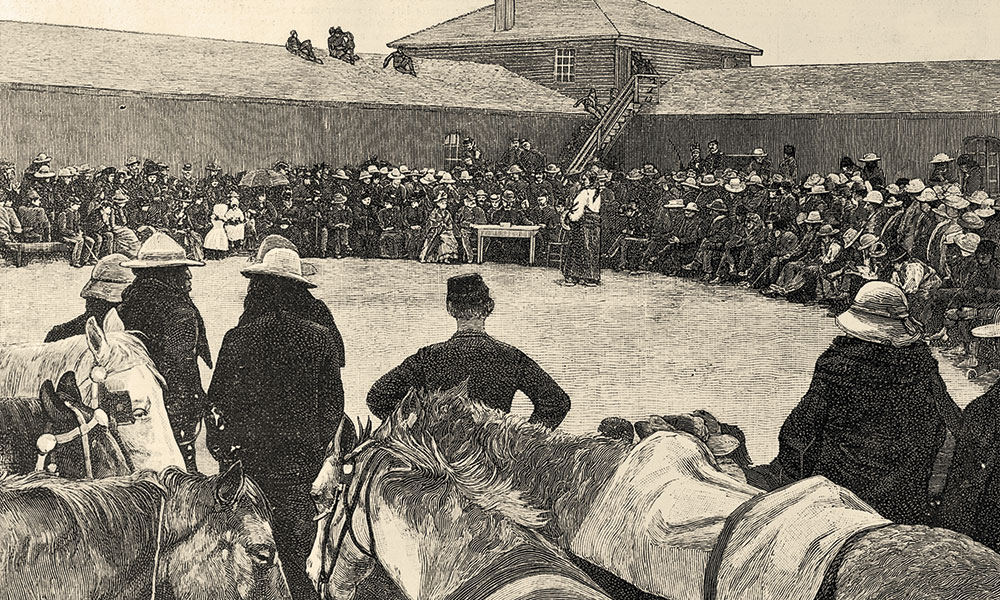

On December 15, at Bull Head’s home, 28 Indian policemen gathered. “The moment was somber; some had fought with Sitting Bull at Rosebud and the Little Big Horn. Others had starved with him in Canada,” Sitting Bull biographer Stanley Vestal reported. All were aware that they stood on hallowed ground; Bull Head’s home was nearly the exact site on Grand River where Sitting Bull had been born 59 winters before.

Sitting Bull was sleeping on his pallet with the elder of his two wives and one of his two small children when police arrived. As he got dressed, he sang a farewell song to his family. Then he walked out of his cabin.

A crowd erupted, shouting, “You shall not take our chief.”

In the frenzy, Catch-the-Bear shouldered a Winchester, aimed and fired. Bull Head’s right side ripped open. As he fell, he grabbed his revolver and shot Sitting Bull in the chest. Red Tomahawk fired into the back of the head, killing Sitting Bull.

During Sitting Bull’s assassination, his horse arched his neck and pranced in a circle. He bowed, then stood up and pawed the ground, reared up and leaped into the air. He cantered around and around in a circle. He did all of this while the battle raged around him, never touched by a bullet. Or so goes the legend.

His famous costar dead and gone, Cody bought the horse from Sitting Bull’s widows. “Sitting Bull’s horse has been shipped from Mandan to New York by express,” reported the Aberdeen Daily News on June 17, 1891.

In 1893, the horse appeared at the Columbia Exposition in Chicago, Illinois. On the midway, Sitting Bull’s cabin was on display, dismantled and shipped from the Plains. Inside, two women said to be Sitting Bull’s widows sold baskets and moccasins. The exhibit netted the exposition company a hefty sum of $2,575 (roughly $70,000 today). The frontier crime scene had become a bonanza.

President Harrison would later tell Cody he regretted rescinding the order. He explained that philanthropists had convinced him that a visit from Cody would have caused Sitting Bull’s death. “So,” Cody wrote, “it was to spare the life of this man that I was stopped!”

All for a political donation. Sitting Bull would not have been surprised.

Deanne Stillman is the author of this edited excerpt of Blood Brothers: The Story of the Strange Friendship between Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill, published by Simon & Schuster, in October 2017.