The Ghosts of Mountain Meadows

“The scene of the massacre, even at this late date, was horrible to look upon. Women’s hair, in detached locks and in masses, hung to the sage bushes… Parts of little children’s dresses and of female costume dangled from the shrubbery or lay scattered about and among these…there gleamed bleached white by the weather, the skulls and other bones of those who had suffered.” —Major James Carleton

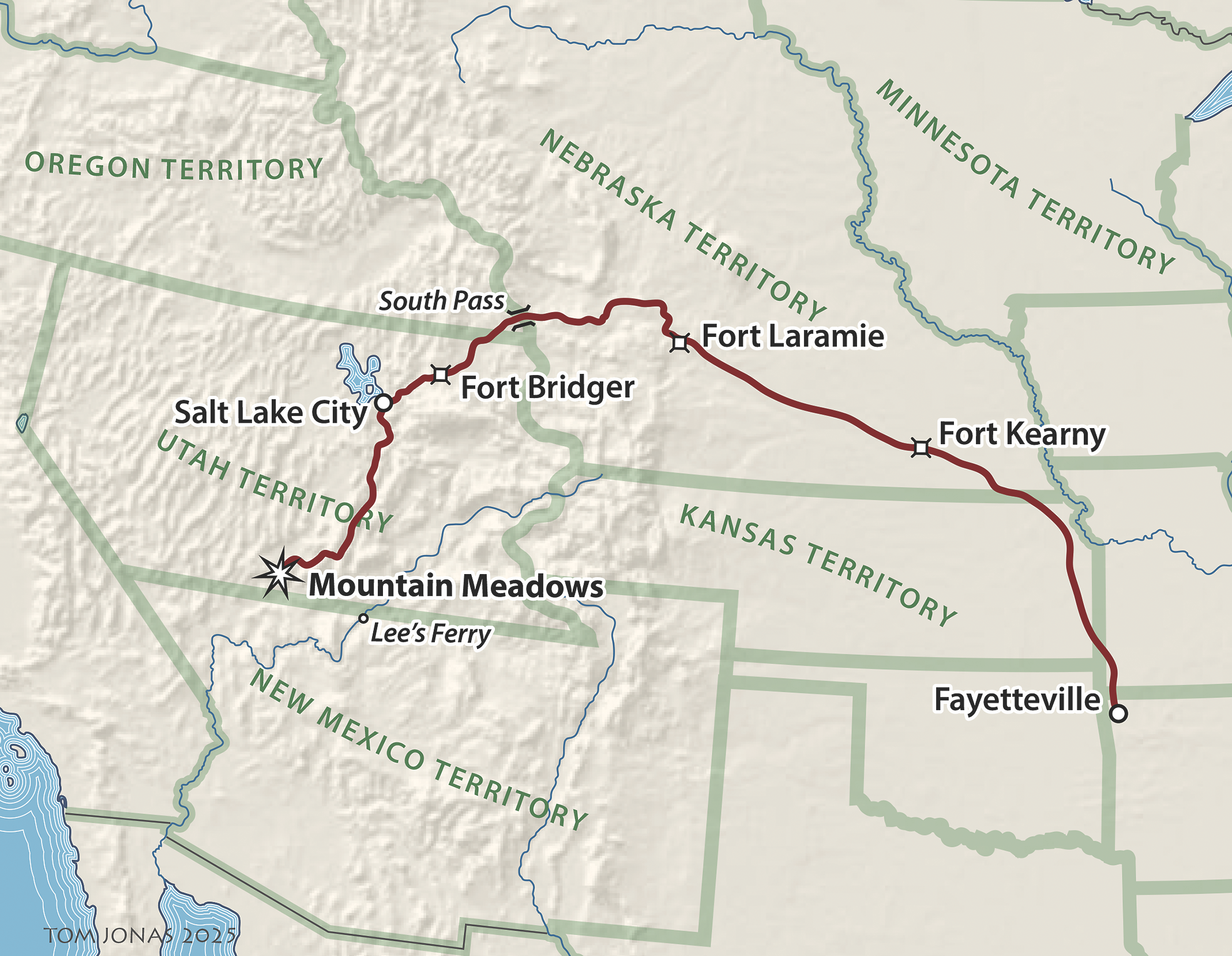

In September 1857, the members of the Fancher Wagon Train, enroute from Arkansas to southern California via the Old Spanish Trail, encamped in an idyllic oasis high in the mountains of southwestern Utah Territory, on the very cusp of the Great Basin. It was a well-off party of over 120 souls, rumored to be carrying a large sum of gold coins, and they needed to rest their horses before the terrible desert crossing to the Meadows (Las Vegas) that lay before them. At dawn on Monday, September 7, as the emigrants awakened to boil coffee and cook breakfast, they were suddenly attacked by unknown assailants from the surrounding hills and ravines. The determined pioneers corralled their wagons and drove back the assailants. Without water and with many dead and wounded to contend with, the Fancher party boldly defended their position from attack after attack, inflicting heavy casualties on their supposed Indian foes. They sent messengers out under cover of darkness to the Mormon settlements to the north and to the trail toward California to the south. They were all killed. Finally, on September 11, 1857, Captain John D. Lee of the local Mormon militia approached the desperate defenders under a white flag. He promised to protect them from the Paiutes if they will surrender their arms and accompany his militiamen to nearby Cedar City. The emigrants were divided, but with no water, little remaining ammunition, many dead and several wounded companions, and over 80 women and children to care for, they accepted Lee’s promise of protection. Divided into three groups by Lee—with the wounded and youngest children in wagons—the women emigrants were marched a few hundred yards before a command was given, a single gunshot fired, and a ghastly slaughter ensued. All—save 17 children (under the age of six)—were murdered by the Mormons.

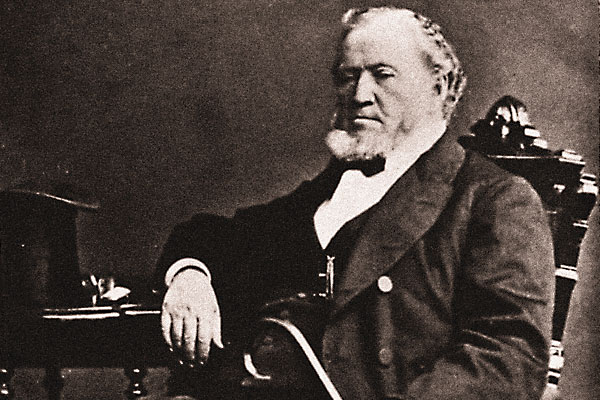

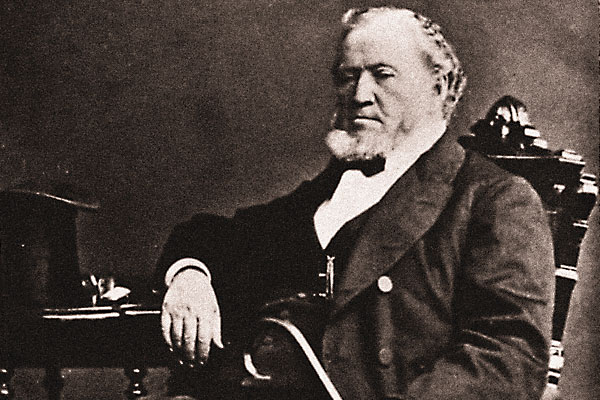

The loot and cattle from the train were divided amongst the murderers and their Paiute allies, and the young survivors were adopted into local Mormon homes. It is the only large wagon train ever wiped out in all of Western history and the greatest mass murder of the 19th century, yet it remains little remembered today. Only one man—John D. Lee—was ever punished for the crime. An elaborate cover-up protected the murderers and those who gave the orders for 140 years. Then, in August 1999, a backhoe operator employed by Mormon Church officials to repair a deteriorating marker at the site unearthed a mass grave of 28 victims. The bones were taken to the University of Utah where forensic anthropologist Shannon Novak and her team made some surprising discoveries before the governor of Utah (a descendant of the murderers) ordered the bones immediately reburied. But the ghosts of Mountain Meadows had already spoken—casting a new light on a forgotten atrocity. Now, through Novak’s studies, as well as books by Will Bagley (Blood of the Prophets, 2002), Sally Denton (American Massacre, 2003), and Jon Krakauer (Under the Banner of Heaven, 2003), a new story had emerged—one that made it clear that White men, not Indians, were the killers at Mountain Meadows, and that the order for the great September 11 mass murder may have come from the highest of religious authorities. Brigham Young, a charismatic and powerfully built New York carpenter, emerged as the leader of the Mormons after a bitter power struggle after the murder of church founder Joseph Smith. This American Moses led his people westward to the Salt Lake Valley of Utah—then Mexican territory—in 1847. The people, more zealous than ever after Smith’s martyrdom, followed Young to the new Zion in one of the most remarkable and heroic human migrations in history. In the vast wasteland of the Great Basin, Young attempted to form his perfect theocracy apart from the evil and corrupt U.S. government to the east. He sent settlements south to control the trails and streams of southwestern Utah, and to convert the Lamanites (as the Mormons called the Indians—who they considered the Lost Tribe of Israel). But the United States soon caught up with Brigham Young. The American victory over Mexico in 1848 added Utah to the new continental nation, and the newly elected President Zachary Taylor was stridently anti-Mormon. His sudden death in 1850 put the weak Millard Fillmore in office, and he appointed Young territorial governor, thus legitimizing the theocracy already in place. President Franklin Pierce continued Fillmore’s policy so that Young’s power in Utah was totally unchallenged. The California gold rush allowed the Mormon settlements to prosper as they furnished supplies to the emigrants passing through, but it also led them into conflict with the “Gentiles.” In 1853, Captain John Gunnison and his seven-man surveying party were killed in southeastern Utah, supposedly by Indians, but it was widely rumored that the murderers were Mormons disguised in warpaint and feathers.

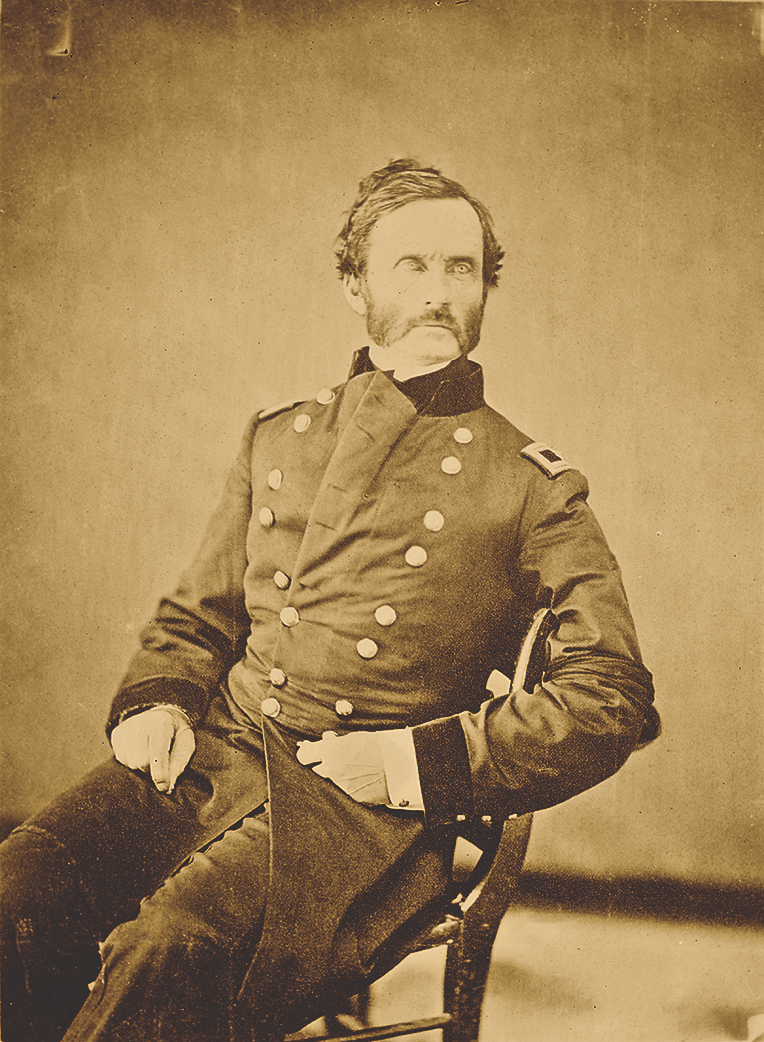

President James Buchanan, anxious to divert attention from the heated sectional rivalry over slavery and outraged by the flight of all federal officials from Utah in 1856, ordered General Albert Sidney Johnston (soon-to-be-famous Confederate officer) to Utah with 2,500 troops to suppress the Mormon rebellion and reestablish federal authority. At the same time, Brigham Young was exhorting his people to a grand “reformation” of their faith. Religious fervor was never higher as Young’s so-called “Avenging Angels” moved through the settlements, enforcing conformity. Into this simmering cauldron came the Fancher wagon train, some 40 wagons strong, in August, 1857. They encamped near Salt Lake City hoping to resupply, but nobody would sell them anything. A Mormon emissary approached Captain Alexander Fancher and urged him to turn south where they would find good grazing for their stock. On August 5th, the wagon train headed south out of the Salt Lake Valley. Brigham Young felt assailed by enemies from every quarter in the dark winter of 1856-1857. Apostates within his own church—which he ruled with absolute, unquestioned power as “Prophet, Priest and Revelator,” answerable only to God—were challenging his authority, recalcitrant federal officials had fled the territory claiming their lives to be in danger, and now a 2,500-man federal army was marching westward to enforce federal rule over the Utah theocracy. Young struck against enemies both internal and external. Whipping his followers into a religious frenzy with a “reformation,” with backsliders and apostates to be eliminated by his special army known as the Danites, or “Avenging Angels.” While Danites burned down Fort Bridger and the Wyoming grasslands to slow the army, others in the south—most notably John D. Lee and Jacob Hamblin—were ordered to ensure that the local Indians would fight alongside their Mormon friends against the American enemy.

Into this climate of hate and paranoia blundered the Fancher wagon train. Many considered this the wealthiest party to ever cross the plains, for the Fanchers and Bakers had converted everything into gold and cattle—with $100,000 hidden in their wagons and a large number of cattle and horses to stock new herds in California. “A prize to tempt unscrupulous men,” noted one Arkansan. The party of 40 wagons was mostly made up of the families of Alexander Fancher and John Baker from Arkansas. They found the locals hostile and suspicious. Salt Lake City had become the resupply center for wagon trains on both the Oregon and California Trails and indeed the city’s prosperity was built around this commerce, but now no one would sell anything to the Fancher party. Mormon hostility to outsiders was at a fever-pitch, but further compounded for the Fancher train by the arrival a month before news of the shocking murder of Parley Pratt—one of Joseph Smith’s original 12 apostles—in Arkansas (although shot by a jealous husband whose wife he had seduced and married, Pratt was promptly anointed by Young as a new martyr to the Mormon faith). A leading Mormon, Charles Rich, approached Fancher and ordered the train to leave the next day. He urged them to depart from their planned route westward across to the Sierra and instead take the southern route where they would find better grass. Twenty years later Young would claim that Rich had said just the opposite—it is a critical point, for some believe that the order to unleash Indians on the Fancher train had already gone south. Certainly Apostle George A. Smith, who had originally organized the southern Utah militia left Salt Lake City on the day the Fancher train arrived with orders from Young for all settlements to hoard their provisions and crops, not trade with any gentiles, collect their guns and ammunition, and prepare for war. Smith and John D. Lee met with Paiute leaders some 35 miles west of Mountain Meadows to make certain that they would join with the Saints against the Americans. Smith left satisfied with the loyalty of the Indians and the burning fervor of the southern Mormons.

The Fancher train departed Salt Lake City on August 5 (with four wagons splitting off and heading west). At Lehi, Provo, Nephi, Fillmore, and every other town they were denied supplies. Finally, at Corn Creek, the Pahvant Indians sold them 30 bushels of corn. Mormons would later accuse the emigrants of poisoning the Indians with tainted cattle, but the story has no foundation. On September 1, Paiute chiefs who had come with Apostle Smith to meet with Brigham Young departed Salt Lake City for the south. They seemed in a hurry.

Smith’s party had camped but a few yards from the Fancher train at Corn Creek. Fancher met with Jacob Hamblin, inquiring why the Indians were traveling with his party. By now the Fanchers had been joined by several apostate Mormons seeking passage to safety in California and they were quite wary. The Fancher train picked up its pace, moving rapidly southward, although they now faced the difficult climb to the 6,000-foot mountain passes that would deliver them beyond the Mormon settlements and into the Mojave Desert.

At Parowan they again tried to purchase supplies without success. Little did they know that within the walls of the nearby earthen fort William Dane was drilling the local militia in preparation for battle. Pushing on to Cedar City, they found a Mormon who agreed to grind their Indian corn. He was ordered to stop by the local Mormon bishop, and when he refused, he was excommunicated. The wagon train hurried on, crossing the rim of the Great Basin on Friday, September 4, and reaching the much-anticipated oasis of Mountain Meadows the next day. Captain Fancher, as if overwhelmed with the joy of reaching the supposed sanctuary of the meadows, allowed the wagons to make camp far apart, posted no guards, and settled in for a much-needed rest under a full moon. Fancher planned to rest and refit at the meadows before pushing over the final mountain pass to the great desert beyond. His people enjoyed a restful sabbath, praying together in a large tent they transported solely for that purpose. The cattle and horses grazed while the people prayed and sang. In the surrounding hills, John D. Lee and members of the Mormon militia carefully painted themselves to look like their 100 Indian allies.

At dawn on Monday, September 7, as the emigrants cooked breakfast, the Mormons and Indians attacked. At least seven men fell in the initial volley with another 20 wounded— including Captain Fancher. Strung out and completely taken by surprise, the pioneers nevertheless rallied under the command of Fancher’s son and drove the enemy back. They quickly corralled their wagons and dug rifle pits. Assuming that they had been attacked by Indians, they prepared to defend themselves until rescue came from the nearby Mormon settlements. Atop a hill above the meadows, John D. Lee counted his casualties—which included two of the Indian chiefs, and contemplated his next move. The Mormons contented themselves with long-range sniping and with making off with the cattle herd on Tuesday. On Wednesday, the emigrants—cut off from water and running low on ammunition—sent two messengers north to Cedar City for help. They escaped only to be attacked by Mormons near Richards Spring. One was killed but the second man, although wounded, made it back. Now the emigrants had a new and even more terrible understanding of their predicament.

John D. Lee’s Indian allies began melting away. Siege warfare was not their style. Soon with but 40 warriors left, he called for reinforcements. At least 100 members of the Mormon militia joined him, while others waited in reserve at Jacob Hamblin’s nearby ranch. Late Thursday evening, three of the healthiest and boldest of the defenders crept through the enemy lines with the forlorn hope of reaching California-bound trains to the southwest and seeking help. Lee’s Paiutes were soon hot on their trail. Two men were killed quickly, but the third made it to the Mojave before the Paiutes caught him. On Friday, September 11, John D. Lee came into the emigrant stronghold under a white flag. He told them that he has come with a rescue column of Mormon militia and that the Indians have agreed to let them take the Whites away if they will give up their arms. Captain Fancher, desperately wounded and near death, gasped out a last order not to surrender. The desperate pioneers, grasping at whatever straw was available, simply cannot imagine that what they believed to be fellow Christians would not protect them. They agreed to Lee’s proposition. All the children under the age of eight—the Mormon doctrine age of so-called “innocence”—were placed in a wagon. The wounded men were placed in a second wagon and were directed north by Lee. The women and children follow. The final group of men are each escorted by an armed Mormon militiaman. They walk a few hundred yards toward a nearby hill rising out of the meadow. “Halt—do your duty!” came the command, accompanied by a single pistol shot. Each militiaman turned and shot his prisoner. Nephi Johnson recalled that it all took less than five minutes. Mormons, some of them disguised as Indians, with their few remaining Paiute accomplices, descended on the women and children and butchered them. Lee personally directed the murders of the wounded men, women and children in the wagons. Lee expended considerable energy making sure that his Paiute allies did not make off with much treasure. His orders are clear that the wealth from the Fancher train is to enrich the Church. Later emigrants will notice the great improvement in clothing, furniture and armaments of the once-impoverished Mormon settlements around Cedar City. But the wealth is concentrated in the hands of but a few ecclesiastical leaders. Resentment over this, and horror over what has happened in the Meadows, led many to soon depart the settlements for California.

Lee wrote a report of the horrible massacre at Mountain Meadows and sent it north to Brigham Young. He blamed everything on the Indians, but was so careless that he misdated the massacre by a week. He had only recently received a written order from the Prophet not to molest any wagon trains. Young had negotiated a deal with the U.S. Army to avoid bloodshed and now wanted no trouble. But why does he need an order not to attack them unless there was an original order to attack? After stripping all the bodies of clothing and valuables and carefully collecting the goods from the wagons, the Mormons gathered around their Bishop—Philip Klingensmith—to take a blood oath to blame the massacre on the Indians alone, to never speak a word of what had really happened—and to kill any man who did. The 18 children from the train were taken to Hamblin’s nearby ranch (where one died). Some of the little children are wounded. One of the Mormon murderers recalled how bothered he was that the children cried all night long. Among them was Christopher “Kit” Carson Fancher, age five, who had witnessed his father shot as he lay in his cot, and his mother hacked to death with an axe, while his six brothers and sisters were being slaughtered nearby. Two years later he recalled: “My father was killed by Indians. When they washed their faces they were white men.” The secret could not be kept for long. Major James Carleton proceeded from Fort Tejon, California, with a company of U.S. dragoons, under orders to bury the dead at Mountain Meadows, arriving on May 16, 1859. It had taken months for rumors of the crime to reach the outside world, and far longer for its enormity to sink in. It was difficult for Americans to believe such a thing was possible. Much effort was expended in rescuing the children. By 1859, 17 were returned to relatives in Arkansas. Brigham Young billed the federal government for the two-year food and lodging provided to the children. The government paid, the indecisive Buchanan administration having no stomach for conflict and facing a far greater challenge from the restless South over slavery. While his government might lack conscience, Major Carleton did not. The scene at Mountain Meadows horrified him. “The scene of the massacre, even at this late date, was horrible to look upon. Women’s hair, in detached locks and in masses, hung to the sage bushes… Parts of little children’s dresses and of female costume dangled from the shrubbery or lay scattered about and among these… there gleamed bleached white by the weather, the skulls and other bones of those who had suffered.”

Nearly every skull Carleton retrieved in his careful examination of the field “had been shot through with rifle or revolver bullets.” This was no pell-mell Indian massacre, it was a carefully planned mass murder, the major concluded. Carleton had his troopers gather all the bones. He interred them and raised a 12-foot rock cairn above the mass grave upon which was written: “Here 120 men, women, and children were massacred in cold blood early in September, 1857. They were from Arkansas.” A rough-hewn cross was placed over the grave on which was carved “Vengeance is mine. I will repay, saith the Lord.” But there was to be no vengeance, or justice. As the nation plunged into the Civil War, the Utah troubles were quickly forgotten. Brigham Young, delighted with the destruction of the Union, traveled to Mountain Meadows in May 1861. Seeing Major Carleton’s cairn, Young responded to the inscription by declaring “Vengeance is mine and I have taken a little.” He then gave a Danite signal by raising his right arm toward the sky, and one of his aides threw a rope around Carleton’s cross and pulled it down. Within minutes the cairn was dismantled. A year later, U.S. soldiers would rebuild the rock cairn, only to have it again dismantled by the Mormons. Efforts to erase the past, however, proved ineffectual even for Brigham Young. Much to the prophet’s chagrin the Union triumphed in the Civil War, and the victorious Republicans had little use for Mormonism. Young, ever the survivor, now distanced himself from his adopted son John D. Lee. He ordered the 58-year-old to depart his prosperous ranch near Cedar City and move south to the Arizona desert. In 1870, Lee—a devout Mormon for 32 years—was excommunicated. All but seven of his 19 wives deserted him as he moved to the confluence of the Colorado and Paria Rivers to operate a ferry. Today, the place still bears the name Lee’s Ferry. Lee’s fate had already been sealed by the confession of Bishop Klingensmith on April 10, 1871, in the Nevada district court (where he had fled for safety). He revealed that it was the Mormons, not the Indians, who had killed the emigrants. The leader of the Mormon militia, reporting directly to Brigham Young, was John D. Lee. The official Church party line that the Indians did it crumbled, and the authorities in Salt Lake City now focused on a new villain—that unfortunate zealot John D. Lee. Brigham Young died soon after in 1877, leaving behind 23 wives (out of 56), 57 children, and a deeply troubled legacy. The question of who ordered the murders at Mountain Meadows died with him. The question of how to deal with the historical legacy of the murders did not.

The Church believed that in sacrificing Lee they had solved their problem. Indeed, the massacre faded almost entirely from national memory. To dredge it up smacked too much of religious intolerance to 20th-century Americans. Utah finally abandoned polygamy and was admitted to statehood, as Mormonism moved from outside the American mainstream to embracing the most American of values. No one wanted to rock the boat. In 1932, the Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Association erected a neutrally worded monument at Mountain Meadows. Strangely, the state provided no road signs to the site and soon the dirt road to it became impassable. The massacre haunted southern Utah. The ghosts could not rest. In 1919, young schoolteacher Juanita Leavitt—a descendant of a participant—was approached by old Nephi Johnson. He wanted to tell her a story and he wanted her to write it down before he died. But they never found the time. She heard that Johnson was dying and rushed to his home. She found him delirious. “Blood! Blood! Blood!” he cried, over and over. The teacher asked a relative what was the matter for he acted as if he were haunted. “Maybe he is,” came the reply, “for he was at Mountain Meadows.” Nephi Johnson died at age 86 on June 6, 1919. He never fully told his story. But the schoolteacher who he confided in went on to write a book that challenged the authority of the church she loved and brought a forgotten tragedy back into the public conscience. Juanita Leavitt Brooks spent nearly five decades researching the story of the Mountain Meadows massacre. She suffered the condemnation of her neighbors and of the Church authorities, but her 1950 book—The Mountain Meadows Massacre—restored that fatal moment in time to the historical record. Eastern publishing houses turned it down, but Stanford University Press finally published it. When a movie deal seemed eminent, Church authorities applied pressure to kill the deal. But the book had legs, remaining in print to this day. Despite her hesitancy to blame Brigham Young, and her too ready acceptance of the lies of Indian complicity, Brooks’ efforts to vindicate John D. Lee and expose the collective guilt for the tragedy became a classic. Interest in the tragedy was renewed, although many historians preferred to ignore such an unpleasant story. Among Mormon historians, the party line remained that “the Indians made us do it.” In 1961, Lee was restored to the Mormon Church, Brooks had won her battle, but a greater one remained.

The True Hero of Mountain Meadows

Juanita Leavitt Brooks

Everyone still puzzles over the simplest of questions—the one that defied an answer— Why? The doctrine of blood atonement? Religious fanaticism? The orders of Brigham Young? Simple greed? How could such supposedly decent, devout men commit such an unspeakable crime? Standing on the hill above the green valley known as Mountain Meadows, one has a sense of loneliness and isolation. Looking down, you can see the sterile but elaborate 1999 LDS memorial already sliding into a rapidly eroding ravine. Bones occasionally appear in the ravine. Looking to the north,

you can follow the path from the wagon siege site (where the monument is) to the low hill where the militiamen murdered their victims. The hush is chilling. The ghosts of Mountain Meadows remain—still seeking justice.