Jedediah Smith is considered one of the great Western explorers, blazing trails from Missouri to California in the 1820s. He was the first to enter California from the east. And then he and his company turned north, moving to Oregon before returning to St. Louis.

Less-known is Smith’s second-in-command during his expeditions of 1826 and 1827. We know virtually nothing about Harrison Rogers—how old he was, where he came from, why he was given such an important role in the Smith journeys. But one of his tasks has had long-lasting impacts.

Rogers was the clerk, the man who kept journals of everyday experiences. Each evening, he took pen to paper to record what had happened in the preceding hours. Some entries were vitally important, recording the paths taken, the Indians that were encountered, native flora and fauna, and more. Some were pretty mundane.

For example, the expedition was held virtually captive by Spanish officials in California in 1826. Very little happened as Smith tried to convince the territorial governor to let the American group return home from their “base” at the San Gabriel Mission. Here, on December 6, 1826, Rogers wrote, “Early this morning I presented the old priest with my buffalo robe and he brought me a very large blankett and presented me, in return, about 10 o’clock. Nothing new. Things going on as they have been heretofore; no answer from the governor as yet; we are waiting with patience to hear from the governor.”

The governor finally let them go. And they broke their word, heading north instead of east.

The tale of the journals is itself extraordinary. Smith and Rogers and company undertook another expedition in 1827; Smith was tasked with keeping the journals. Again, this trek went to California before heading north to Oregon. On July 14, 1828, Rogers and most of the group were killed by Umpqua Indians. For whatever reason, the Natives took Rogers’s journals from his body. Smith desperately wanted them back, so he went to British authorities in Vancouver who were on good relations with the Umpqua. After a few months of negotiations, the journals were returned to Smith, who in turn took them back to St. Louis.

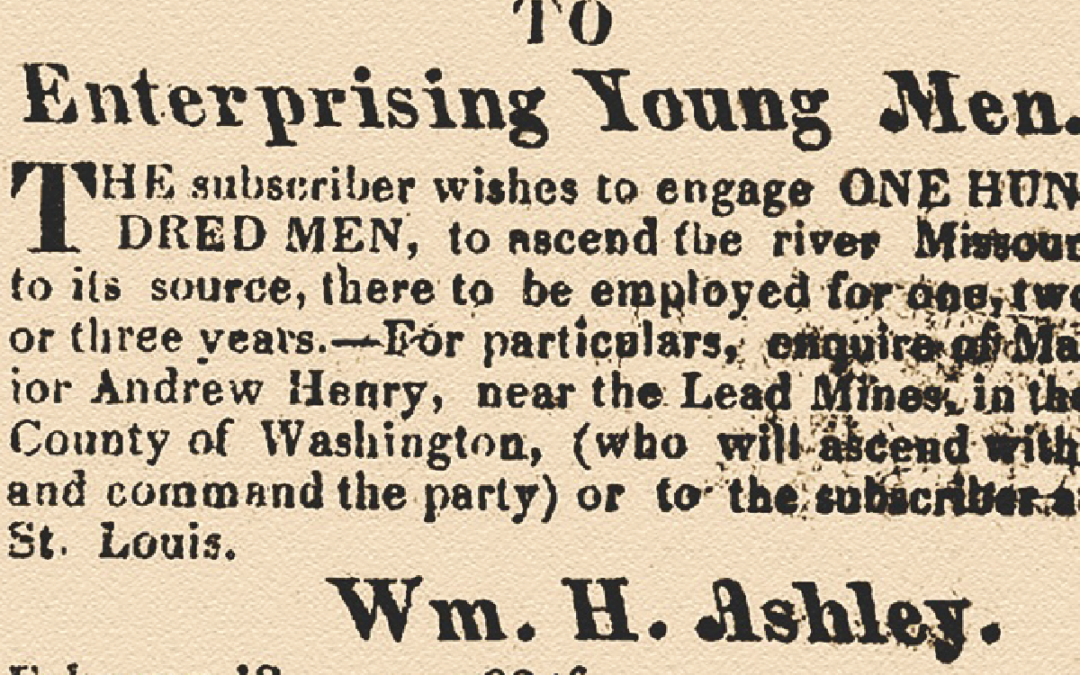

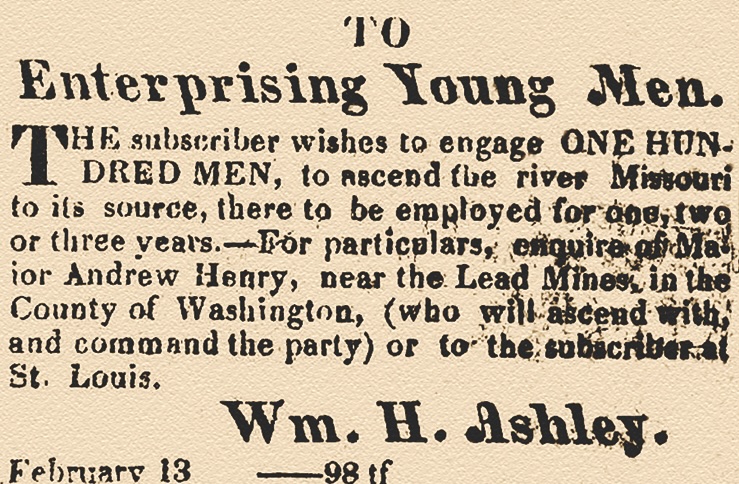

Before heading out on yet another expedition, Smith left the papers in the care of partner/executor William Ashley. Smith was killed in 1831. Ashley preserved the journals, then handed them down through his descendants. Around the turn of the last century, the journals were donated to the Missouri Historical Society, but they were primarily available for research purposes only.

They were finally published in 1918—90 years after Rogers’s death and the end of his adventures. His journals had their own adventures and stories to tell.