Long before the “ordinary” white men braved the arduous task of crossing into the “Great American Desert” and beyond. Long before latter day explorers “discovered” the mountain passes through the Rockies, Sierra Nevada and Cascades to California and Oregon. And long before the cowboys drove the longhorns north or the miners and prospectors went west to dig for precious metals the mountains held, a fearless intractable, reckless breed of men challenged the vast unknown for another kind of treasure.

The market for beaver furs in the first half of the 19th century provided the incentive for businessmen in search of wealth and young men in search of adventure. From the now-famous advertisement run by William Ashley in 1822 when he sent out a call that attracted such storied names in the annals of trapping as Jim Bridger, Tom Fitzpatrick, David Jackson, Jim Beckwourth, Hugh Glass, Antoine Leroux and Jedidiah Smith…..”to all enterprising young men.” All were part of what became known as “Ashley’s Hundred.”

Until it went into decline and the near extinction of the beaver in 1840 the fur trade was one of the vanguards of American industry. John Jacob Astor was comparable such latter-day giants of industry as John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford and Cornelius Vanderbilt.

It was a time when every man wore a hat and every hat was made from the hide of the beaver.

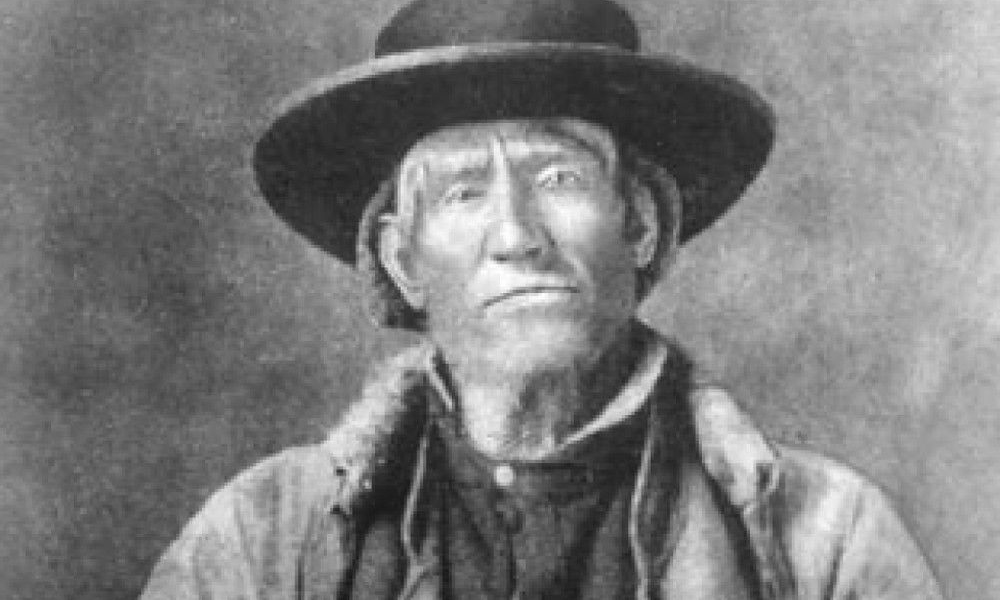

The men who took part in the fur trade left an impact on the Far West that is immeasurable. Not many were literate so the details of their adventures are scarce and few records were kept. The West at the time was a vast social outlet and some of the trappers, ostracized from their former societies, went native in the new land marrying into Indian tribes, adopting their cultures and never went home again. They were described as men with “little fear of God and none at all of the devil”

The even developed a descriptive, colorful lingo some borrowed from the Indian and some of their own; winter was known as “freezin’ time,” a celebration was a “big dance” and to run was to “make tracks.” A man was a “chile,” “hoss,” or “coon.” To scalp a foe was “to tickle his fleece” and a friend who died or was killed had “gone under,” or had been “rubbed out.”

Not all were uneducated and informal gatherings to discuss, argue or debate was dubbed the “Rocky Mountain College,” where those who were literate, read from the works of Byron, Shakespeare and Scott. They might even discuss such topics as geology, chemistry, philosophy and Bible scripture. Those who couldn’t read enjoyed listening.

For most, the life of a mountain man was a half-civilized and half savage existance. Some crossed that line that separates a man living a man living a savage-like life to one who became a savage. Take for example Ed Rose, a moody, sullen, misfit who joined the Crow tribe and became a chief. In 1834 another trapper witnessed him lead Crow warriors against a band of Blackfoot. He whipped his followers into a bloody rage, hacking the hands off the wounded adversaries and mutilating the corpses of the dead.

Charlie Gardner was nicknamed Phil because he hailed from Philadelphia. He once rode into the mountains with an Indian companion. There was a violent storm and the two were given up for dead. A few days later Phil rode into camp alone. He pulled a piece of a human leg out of his pack, tossed it aside and said. “There damn you; I won’t have to gnaw on you anymore.”

Thereafter his friends called him “Cannibal Phil.”

It was claimed that sometime later he spent another frigid winter in the mountains; this time the object of his culinary work was his Indian wife.