This idol of millions spent his last evening on earth with old friends, old memories—but new hopes. And no Hollywood premiere was ever more dazzling than the Arizona sky which was his final backdrop…

Illustrated by L. A. Wolfe

I WAS SHORE RIDING the old gravy train writing Western stories for the pulp paper magazines, getting high rates per word and averaging two and three thousand words a day, keeping my blunt nose to the grindstone six days a week, getting up at sunrise and working four or five hours before calling it a day, and never missing a deadline. A far cry from punching cows for 40 dollars a month and beans.

I was living high on the hog, spending money like a cowboy in town, always bearing in mind the trite old saying that there’re no pockets in a shroud. Most mebbe I had a mild case of what the cowboys call Stetson Fever. Buying drinks for the house and enjoying life to the hilt. As the feller says, spending my money on houses and lots. The houses being saloons and lots of booze.

It was my thrifty wife who saved enough money to buy a tract of land in the Catalina Foothills Estates in Tucson, Arizona. Sixteen acres on a hill that commanded a view from all compass points of five mountain ranges, the Santa Catalinas, the Rincons, the Tucson Mountains, the Santa Ritas and the Tortillas, and on a clear day you could see plumb into Old Mexico. We contracted for the building of a Spanish-type house constructed of burnt adobe, and by the time it was completed by builder John W. Murphey and architect Joseph Jossler, it was really a showplace. The glassed and screened front porch was 66 feet long, with the master bedroom on the east end and a guest room on the west. The living room, game room and den were in between, with servants quarters and laundry and storeroom in the rear.

We furnished the entire house with black walnut furniture, handmade and hand-carved by a master craftsman, E. Garrett Anderson of California. Each piece of furniture was made separately, and it took almost five years to complete the furnishings. The switch plates throughout the house were made of hand-hammered Arizona copper; the doors were all hand-carved by a Mexican wood carver and decorated with antique iron hinges and locks. The floors were of polished tile from Mexico, the drapes hand-woven and hand-painted by local artists. The patio in the rear was flagstone with a large sunken firepit and a three-foot burnt adobe wall around it. Giant saguaros and other cacti and native shrubbery covered the 16 acres, and below and out of sight from the main house, was my one-roomed adobe workshop with a large picture window that offered a view of the Santa Catalina Mountains to the north.

There was a corner fireplace, flagstone floor, and a small porch facing south, and the door was a divided stable type, so that during warm weather the top part of the door could be opened to let the sun in. There were no electric lights, no bothersome telephone, thus affording the privacy I needed. Plumb out of sight and beyond earshot of any visitors who might drive up of a morning. Anyone who tried to reach me by telephone could leave a message for me to call back when I came up to the house for lunch, the day’s work done and the stable door of my shack closed. The word “studio” I never used in connection with my workshop. I called it my shack and that went as she laid. All this gives the reader a sort of background for the story that follows.

THAT warm sunny day in October 1940 when I closed the stable-type door of my shack and came up to the house about noon was destined to remain branded in my memory for all time.

My wife had gone to town and had left a message on the telephone pad in the den. The message was from Sheriff Ed Echols saying that he was bringing Tom Mix out that afternoon for a drink, As a rule when I’d finished work and had lunch I headed for Bill Coleman’s barn where I kept the buckskin cowpony Tex that Bill had given me. I would saddle up and ride until suppertime. Once I rode into the foothills I could relax and forget the story I carried inside my boneheaded skull. Tex was strictly a one-man horse and always those yellow eyes were watching for something to spook at, with his short black ears cocked forward to listen. When a flock of quail winged off with a whirring sound a few feet ahead, Tex would whirl and jump sideways and charge off through the mesquite and catclaw brush. You shore as hell had to keep awake when you forked old Tex. It had gotten to be a game we played, me’n Tex, and both of us enjoyed every minute of it. Tex had a keen eye and if he saw a bunch of stray cattle grazing he’d head for them, expecting me to rope a calf just for the hell of it.

But with company due to show up I would have to miss that afternoon ride. I took a shower and shaved and got dressed in my town gabardine riding pants and new pair of alligator boots, and then went to the kitchen to grab a ham sandwich.

I had just finished eating when the front doorbell rang, and when I got out on the screen porch there stood Sheriff Ed Echols and Tom Mix, and the sheriff’s car was parked on the gravel driveway in front of the long hitchrack.

The bell was originally an altar bell from some old mission in Mexico, and it was attached to a coiled spring with a rawhide rope for a pull. Tom kept giving the rope a little yank and listening to the deep tone of the bell and its soft echo. He’d cock his head sideways, his white Stetson at a jackdeuce angle, a sort of half smile on his lips as he kept ringing the bell. Years of erosion had almost obliterated the date of 1780 on the rough bronze casting.

“If you ever take a notion to sell that old bell,” Tom said as I opened the door and let them in, “I’d like to have it. Where the hell did you ever get it?”

“My wife brought it back from Sonora, Mexico,” I explained. “When all Catholic churches and missions in Mexico were closed and the priests and nuns were run out, some of the faithful Mexicans took all the santos and priest’s robes, all bells and bronze baptismal fonts, and buried them in the ground. My wife gave it to me as an anniversary present, so it isn’t for sale, Tom, for sentimental reasons. Or I’d give it to you.”

“When a man’s been married half a dozen times,” Tom Mix smiled sardonically, “any sentiment about wedding anniversaries is cold as the ashes of last year’s campfire. Payin’ all them alimonies sorta drowns out the romance.”

I led the way into the bar, and the three of us had a drink. Again Tom Mix’s attention was fixed on a genuine old oxbow complete with wooden hoops that once fitted over the necks of oxen. I explained that it was a present from Tex Wheeler, the sculptor and artist. Wheeler was born and raised on his father’s ranch in Florida, and he and our neighbor, Rubin Jelks, who bred racing quarter horses, had gone to Florida for a visit and had brought the oxbow back tied to the front bumper of their car. I’d had the electrician convert a couple of old railroad lanterns to electric lights and they now hung from the oxbow over the pool table in the game room.

Tom was also interested in the small disappearing bar behind doors which were covered with cowhide and studded with hand-hammered Arizona copper nails. He insisted on a guided tour of the whole house and my shack, which took about an hour.

Back on the porch we made ourselves comfortable, with our drinks resting on the broad arms of rawhide-laced and cushioned chairs. We rolled our own cigarettes, not with Bull Durham but from a caddy of English Three Castles tobacco I ordered from the London Pipe Shop in Los Angeles.

WITH cigarettes lit—and warmed by good whiskey—Tom Mix and Sheriff Ed Echols began swapping yarns. Ed had the cowpuncher brand of dry humor that had won fame and big monied glory for the one and only Will Rogers, an old-time friend of the three of us. Ed Echols had operated a cow outfit in Arizona before he became sheriff of Pima County. Both Mix and Ed had worked as cowhands, and Mix had won the bulldogging at the Seattle, Washington, rodeo in 1909, and Ed had won the steer roping at the Calgary Stampede in 1912.

Ed and Tom got to telling about traveling with the Zach Miller 101 Wild West Show, and about all the cowhands who rode broncs and roped steers and bulldogged—men such as Bill Pickett, Neal Hart and Henry Grammer.

“I worked on the spring roundup,” Tom Mix said, “up in your part of the Montana cow country, Walt. Punched cows for forty-a-month for the Circle Diamond when Johnny Survant was the wagon boss, along about 1904-1905. Me’n Henry Grammer hired out to work for the outfit.” Tom sloshed some whiskey into his tall glass to cover the ice cubes. You recollect the time Grammer shot that sheepshearer in a saloon ruckus in Malta?” He asked me.

I said I was at the Circle C ranch at the time and had heard the story from Jake Myers, the Circle C wagon boss who had been born and raised in Oklahoma where Grammer came from. Jake claimed Henry Grammer was a good cowhand and one of the best ropers in any man’s cow country—that Grammer was on the wild side and tough as a boot. Jake said that the spring roundup was just over with and the Circle Diamond outfit had just pulled in at the home ranch. Henry Grammer had gone to Malta and had killed some sheepshearer who had been bothering some old sheepherder. The sheepshearer, tough in his own right, had pulled a knife and made a pass or two at Grammer. Grammer was unarmed, having left his six-shooter on his bed at the ranch on Milk River. The sheepshearer’s knife had slashed the front of Grammer’s shirt across the and he had cussed out the Oklahoma cowpuncher, telling him that he was going to spill his guts out. Henry Grammer then jumped over the bar and grabbed the bartender’s gun and killed the sheepshearer.

Grammer, still armed with the bartender’s six-shooter, was buying drinks for the house when the constable at Malta came in to arrest him. Grammer told the deputy that nobody but Sheriff Puck Powell was going to put him under arrest. (At that time Puck Powell was sheriff of Velley County and stationed at Glasgow, the county seat.) Grammer told the constable to get in touch with Powell and tell him that he (Henry Grammer) would be at the Circle Diamond ranch on Milk River, a few miles from Malta, where he would give himself up without any trouble. And that’s what happened.

Johnny Servant, the Circle Diamond wagon boss, foreman and ramrod for the Bloom Cattle Company who owned the Circle Diamond outfit, hired the best criminal attorney in Montana and laid cash on the line for bail bond money. At the trial Henry Grammer’s plea was self-defense, and he was sentenced to three years in the state penitentiary at Deer Lodge. He served out his sentence, with time off for good behavior.

So I was familiar with the story of that shooting scrape of Grammer’s, although I was a kid at the time. I remembered there had been many different” versions of the killing. One was that instead of a knife, the sheepshearer packed a heavy railroad spike sharpened to razor’s edge on a grindstone—

that the husky, tough sheepshearer had cut and slashed the unarmed Oklahoma cowpuncher until he had hollered quits. “I’m going out to get my gun,” Grammer was said to have told the sheepshearer. “I’ll be back directly and you’d better have a gun in your hand, because I aim to gut shoot you.”

As the three of us sat on the porch I told them of the different versions I had heard. Tom Mix said he wasn’t there when Henry Grammer killed the sheepshearer who had abused an old sheepherder and Grammer had played out the old man’s hand with a six-shooter. Mix said that when Grammer had served his time in the pen he had headed south to Oklahoma to join his roping pardner. Clay McGonigal—that at one time or another both these men had held steer roping records, as well as team tying records, at all the big rodoes.

I WAS CONTENT to just sit back and listen while Tom and Ed talked about rodeos, with humorous anecdotes about different bronc riders, ropers and bulldoggers who had hired out to the Wild West Show. Then they went on to talk about the big rodeos and the Calgary Stampede, from the time of the first cowboy contest, claimed by Prescott, Arizona, in 1888, up to the present era.

One of Tom Mix’s daughters had married Harry Knight from Calgary, Alberta, one of the top bronc riders of all time. Harry Knight was then living at Florence, Arizona, where he was in the cattle ranching business with Twain and Bill Clemens (descendants of Mark Twain). Despite the fact that the champion bronc rider and Mix’s daughter had agreed to split the blankets, Tom Mix and Harry Knight were close friends, and Tom said that he was going to stop at Florence to see Harry on his way to California.

Tom had presented me with a small paperbound book he had written about himself. It was titled Ropin’ A Million and there was a head-and-shoulders sketch of Mix on the cover, with his long rope outlined around the sketch and fastened to a sack marked $1,000,000. The story had been reprinted from Photoplay Magazine. I still have in my possession the book he autographed on that October day in 1940.

Tom said he had had it made to make a million, and he’d got the job done and had had a hell of a good time spending a lot of the money.

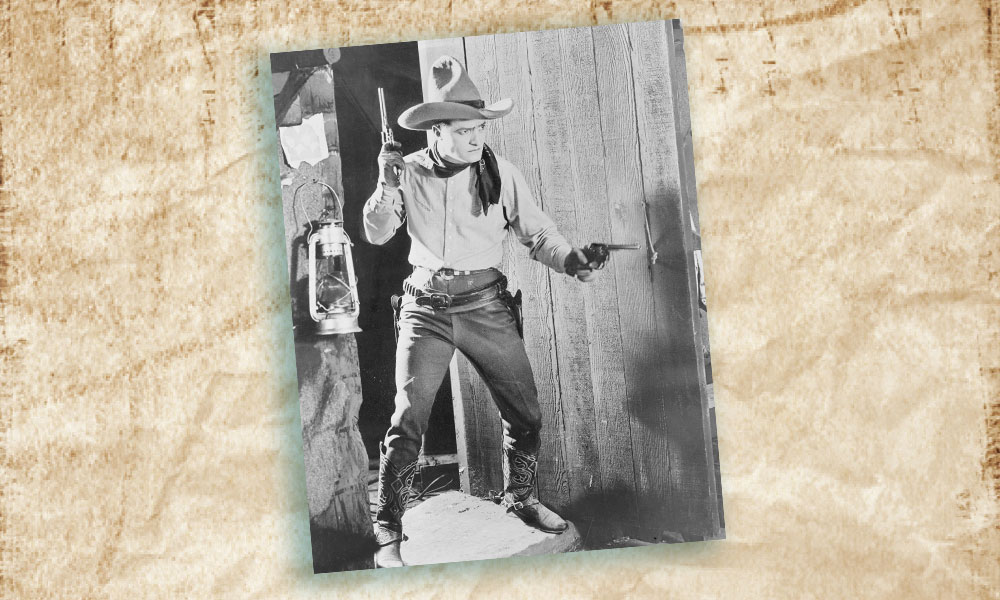

In the book Tom said he had made over 370 moving pictures. Never used a double or stand-in for the dangerous stunts he performed. As a result he had over 150 stitches taken in his hide, plus suffering 23 broken bones and cracked ribs.

“I never claimed to be an actor,” Tom said. “But some newspaper writer claimed I was the best showman on earth, even better than Buffalo Bill Cody who never made a movie in his life. From the start when I made my first starring picture for Fox, I made it a rule to never smoke a cigarette, take a drink, or gamble in any picture I ever made. A lot of youngsters made up a big part of the audience and I aimed to set a good example for them. Instead of using a six-shooter and doing a lot of shooting, I used my fists or a ketch rope, and I kept my pictures clean.” His pictures had made more than five million bucks.

Tom Mix changed the subject to Hollywood script writers. “You’d never believe some of the scripts those white-collared screen writers handed me. Some of the scenes were plumb ridiculous. The motion picture studio conferences were a big joke. All those dude writers ever did was to increase the overhead of the five-reel pictures.”

The following is taken from Tom Mix’s Ropin’ A Million.

“These story conferences are usually run off somethin’ like thisaway:

“Around a long mahogany table, a heap better than Napoleon ever ate off’n, an’ in a room with more furniture than John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford have got in their offices, gather the star, the chief scenarist and three or four of his assistants: This head bird is likely to be drawin’ $1,000 a week; first assistant gettin’ not less than $660 an’ the remainin’ three $500, $360 and $200.

“The $500 an’ $360 a week birds probably were former song an’ dance men, and the $200 man a young chap who wrote an’ achieved doubtful fame as an author of that popular melody ‘Missouri Blues’ or ‘A Lonesome Bird in a Cottonwood Tree.’ Personal, these here scenario writers ain’t never been much help to me because I don’t read music. “But to get back to the story conference. Any conference lastin’ less than three hours ain’t no good. Not that anythin’ is decided upon that gets in the picture but it fills in the day until time to go out and shoot a few holes of golf, the latter bein’ a by-product of the movin’ picture business.

“At these here story conferences all of ’em talk an’ talk an’ talk, but none of ‘em says anything. They seem to get nowhere. Any sµggestions that I may make an’ me a-knowin’ the West, is properly squelched as bein’ out of order. Anytime I talk I am a-speakin’ out of my turn. About the second hour I give up, fix myself comfortable in the big overstuffed leather chair an’ snooze it out, leavin’ them to themselves an’ their own vacuum.”

SO TOM MIX finally decided to write his own script, direct his own pictures, and furnish his own horse for $1,000 a week. Then came the day when the era of silent pictures was out like Nellie’s eye. Replaced by talking pictures, Tom Mix, the King of Western movie stars, was over and done with. And for Tom Mix, the cowboy hero of clean, silent pictures, it was a heavy blow.

Tom Mix had spent the million dollars he’d made with the same reckless, carefree prodigality of a 40-a-month cowpuncher on a town drunk.

In a sort of roundabout, lesser manner, the career of Tom Mix, star of the silent Westerns, and my own career as a writer of pulp Western yarns had something in common. Both of us had come up the hard way from a common cowhand, and at that time I was making more money than I could spend. Tom Mix had pointed out when he was getting a guided tour of the house, that it was a mighty fancy bunkhouse for a cowhand.

It was Sheriff Ed Echols who made the comparison, telling Tom that a month or two before there had been in a local newspaper a picture of me and my horse Tex at the hitchrack in front of our house in the Catalina Foothills Estates, declaring me the King of Western Story Writers.

“There’s times when this young feller goes hawg wild,” Sheriff Ed told Tom Mix. “When him and cowhands like Roy Adams and Buckshot Sorrels and some others take the notion to head for Nogales across the border, it’s always up to me to ride herd on him. Walt and me has made a deal. When he’s likkered up he calls me up and I dispatch a sheriff’s car and a deputy to take him in tow. In a lot of ways you two are alike, Tom, wild and careless.”

All the time Sheriff Ed Echols was talking in his habitual soft tone of voice, there was a sort of grin on his face and a twinkle in his eyes.

“There was a time, Ed,” Tom Mix reminded the sheriff, “when you sowed a goodly crop of wild oats yourself. When you were wild and reckless and didn’t give a damn.”

Sheriff Ed chuckled softly. “Shore thing, Tom. But wearin’ a sheriff’s badge saw’ed my horns off. I had to slow down. But a cowpuncher wearin’ a sheriff’s badge takes care of his own kind, regardless.”

That summed it up in a nutshell, and in my book and Tom Mix’s book Ed Echols was the best sheriff Tucson ever had, and we so declared ourselves and it called for another drink.

After we were again comfortably settled in our chairs on the porch, Ed Echos told us that in April 1907, he had hired out to Miller Brothers 101 Wild West Show. Tom Mix was with the show at the time. It was there that Ed met Will Rogers and they got to be mighty good friends. It was years afterwards when Will Rogers was making pictures in Hollywood and Ed was running the first time for sheriff of Pima County, that Will wired Ed that he’d take a day off and fly over to Arizona to do a little stump-speeching in Ed’s behalf. Which he did.

Will had his pilot set him down in what he thought was a likely town to gather votes for Ed and he made the kind of speech that only Will Rogers knew how to make. Then he flew back to Hollywood where he was in the middle of a picture.

Ed wrote and thanked Will. “But the hell of it was, Will,” Ed wound up his letter, “they throwed out all them votes you corralled for me. You landed in Cochise County instead of Pima!”

We all got a chuckle out of Ed’s story. and after fixing another drink, we were back on the porch talking this and that.

Tom said that he had for a while vanished from the familiar stomping ground of Hollywood to put on his own Wild West Show. For three years Tom Mix’s Wild Animal Show had been a smash hit. He had played 220 stands throughout the country in ten months, still doing his own riding. Now he was returning to Hollywood and the movies. Tom said that during those same years he had been involved in expensive lawsuits. Zack Miller of 101 fame was suing him for a breach of contract. He was also involved in lawsuits over alimony. And as Tom talked, a note of bitterness crept into his rambling. Once a man was beset by troubles, some men he had once called friends were trying to tromp his guts out. But Tom Mix was never a man to call quits. The image Tom Mix had built up throughout the years as a cowboy hero was still intact.

THAT MEMORABLE late afternoon of October 11, 1940 was destined to have one of those rare southwest sundowns that artists depict on canvas. The setting sun was a fire colored crimson in a war painted sky. The distant mountain ranges were a deep purple, the desert haze lingering with the last heat waves stretching into Old Mexico. There was a hushed silence except for the call of the quail as they came from the brush to feed on the grain I had scattered on the feeding ground. Mourning doves crone to feed, and cottontail and jackrabbits came to join the quail and doves. Kit foxes would soon appear at the feeding grounds, as well as chipmunks who chirped and chased one another. The birds would come :!or their evening meal. The kit foxes, timid by nature, seemed to sense that all animals and birds were protected on our land and they would eat their fill of scraps thrown out, drink at the scattered Mexican clay dishes, then stretch out in the cool shade of the mesquites before they left for their den in the foothills.

The three of us sat for the most part in the hushed silence of the sunset—three cowpunchers who knew how to enjoy the quiet, each man lost in his own thoughts and dreams of yesterdays. I was the youngest in years, but we were all young at heart. Big, soft-spoken Ed Echols, with a generous sprinkling of gray in his hair. The black-haired Tom Mix, who had retained his prideful youth.

It was late dusk when my two visitors finally took their departure. The last drink, one for the road, had been drunk. Ed Echols had promised to bring Tom out the next day for lunch, so because we were to meet the following day there were no handshakes or words of farewell.

“So long, Walt. See you tomorrow.” Tom Mix called back as they drove away.

I stood there at the hitchrack and answered, “So long, until tomorrow.”

I’m glad I didn’t know at that moment that I would never see my good friend Tom Mix again.

THE FOLLOWING DAY I quit work early and came up to the house to put the mesquite charcoal in the outside patio fireplace and set the grill in place. We were to have thick tenderloin steaks, and I had a case of Mexican Carta Blanca cerveza that was rated better than American beer.

I had invited the jovial Nick Hall, manager of the Santa Rita Hotel, an oldtime friend of Tom’s, to join us for lunch. One o’clock came and went and no sign of Sheriff Ed or Tom Mix. Nary a sign of Nick Hall. Two o’clock went by. It was along about three when the telephone rang. It was Nick and I could tell by the tone of his voice that perhaps Tom Mix had suddenly decided to head for Florence to see his former son-in-law before going on to Hollywood. And I was right. Tom had done just that, leaving word with the day clerk on duty at the hotel to telephone me that he couldn’t make it for lunch, but the clerk had forgotten to give me the message. I was disappointed, naturally, and I decided to head for Coleman’s barn, saddle up and ride into the hills.

I was just going out the door when the telephone began ringing. It was Nick Hall again, informing me that news had just come in that Tom Mix had been killed in his car. It was later that I got the whole story.

Tom Mix owned a flashy looking Cord that he drove with the top down. The rear seat held his luggage, including a locker trunk. A highway crew was working on the Florence highway and they had put up a barrier with a detour sign. Tom Mix, traveling eighty miles an hour, had smashed through the barrier, turning the Cord over in a dry wash. The heavy trunk had been dislodged with the sudden impact, striking Tom on the back of the head and breaking his neck. He was killed instantly.

Sheriff Ed Echols had immediately gone to the scene of the wreck, midway between Oracle Junction and Florence. A coroner and an ambulance followed Ed. Nick Hall had been busy on the long distance telephone to Hollywood, to notify Mix’s daughters and the studios.

When we were finished talking and I’d hung up, I went into the game room. The folding bar had long since been set up. I poured a big shot of Bushmill’s Irish whiskey and took my drink out on the porch where we had sat the day before. The shock of Tom’s sudden death left me sort of numb and bewildered, and I wanted to be alone for awhile. My wife had already left for town, so I was alone with my grief.

The October afternoon was warm and a few scattered clouds were in the sky, but the sun had lost something of its warmth as I took my drink outside to the long hitchrack. My thoughts were of yesterday when Tom Mix was alive. So very much alive.

There was a strange magnetism about Tom, hero of countless Western movies, which had endeared him to youths throughout the nation. Knowing him as I did in real life, I’d been proud to claim his friendship. Now there was an aching lump in my throat that no amount of good whiskey could dissolve. When I rolled and lit a cigarette, the good tobacco smoke had an acrid taste. I took another drag and stubbed out the halfsmoked stub on the hitchrack. Then I got in the car and headed for Coleman’s barn. I saddled Tex and rode off into the foothills.

I remembered a bit of the conversation of the day before. I’d said that I always rode Tex of an afternoon, regardless of the weather, to get rid of the nervous tension left from my morning’s work. And Tom Mix had said he felt the same way when he rode Old Blue or Tony. Ride off alone and an hour or so in the saddle and our worries were gone.

There is a strange sort of understanding between an old-time cowhand and his favorite horse. That understanding was there between me and Tex. It was as if that yellow-tiger-eyed buckskin cowpony had an instinctive understanding of the grief that was in my heart. Maybe it had been in the tone of my voice as I talked while I was saddling him. Because that day Tex wasn’t looking for something to spook at. When a jackrabbit jumped from the brush a few feet ahead on the trail he kept on traveling at his fast running walk, keeping steady along the winding trail through the mesquite and catclaw and cholla cactus.

I kept talking to Tex, low toned, as I untangled a witch’s knot in the long black mane, telling him how my old friend Tom Mix had died a tragic death that day. I figured Tom was crowding sixty and was past the prime of his life. His career as a star of Western movies was over and done with. Far worse things could have happened to Tom Mix than sudden death. Old age and being broke would have been his ultimate future, and the prideful man could not possibly have taken in his stride old age and its infirmities and uselessness.

Tom had roped his million and squandered the money like a cowpuncher in town. Tomorrow morning his tragic death would be in big black headlines in every newspaper in the United States and other countries. It was a spectacular end to the greatest Western cowboy star that was ever known on the silver screen. If Tom Mix had deliberately planned the manner of his passing it could never have been more fitting.

Tom Mix had seen his last sunset in the welcome companionship of his old and true friend, Ed Echols. A crimson sunset in a spectacular sky, with a panoramic view of the desert and mountain ranges and Old Mexico. He had heard the sound of the quail and mourning doves blending into the bushed twilight of that last sundown.

All men are born to die. But it is given to few men that though they are long dead, they shall never die in the nostalgic memories of at least two generations of Americans who hero-worshipped the image Tom Mix left behind when he crossed the Big Divide. He lived his own legend in real life and on the silver screen, and that legend is destined to live on forevermore.

On the edge of Florence, Arizona, at Tom Mix Wash in the middle of the desert, there stands a rock monument with the statue of a riderless horse. It bears the following inscription:

IN MEMORY OF TOM MIX, WHOSE SPIRIT LEFT HIS BODY ON THIS SPOT AND WHOSE CHARACTERIZATIONS AND PORTRAYALS IN LIFE SERVED BETTER TO FIX MEMORIES OF THE OLD WEST IN THE MINDS OF LIVING MAN.