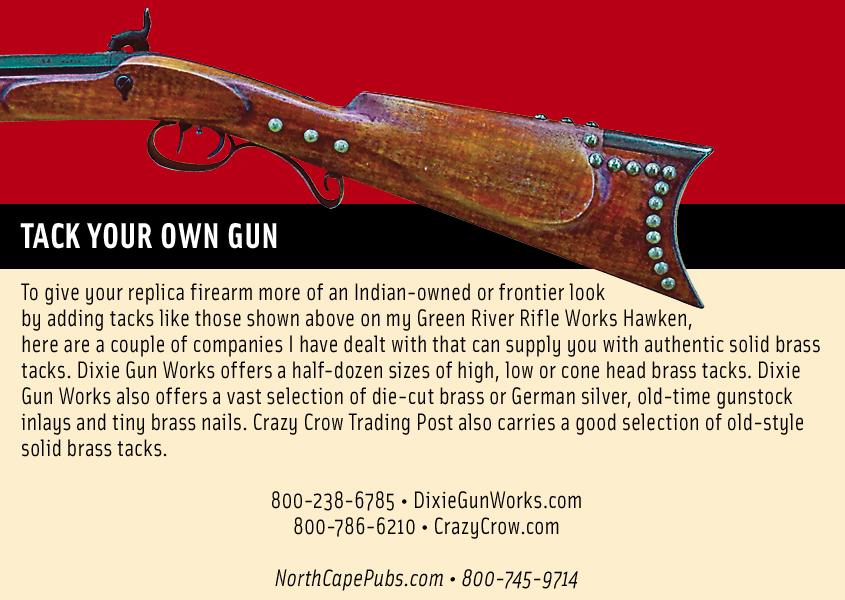

The use of brass or iron tacks to decorate gunstocks, whether for religious or strictly decorative purposes, was a practice of the American Indian as far back as at least the early 1800s.

The use of brass or iron tacks to decorate gunstocks, whether for religious or strictly decorative purposes, was a practice of the American Indian as far back as at least the early 1800s.

One colorful example of Indians using metal tacks to decorate weaponry comes from an 1860s Sioux war chief, Pawnee Killer. Eyewitnesses, who reported the chief stood “six feet four, broad shouldered, and [weighed] 240 pounds…,” stated, “For every Pawnee Indian he kills, a brass-headed tack is driven into the stock of his Winchester rifle, which now contains no less than 130. Hence the name conferred upon him.”

Tacking or applying nail shanks to adorn weaponry was not unique to the American West as this art form can be traced back to some of the earliest firearms worldwide. Nonetheless, with the appearance of the white man’s goods on the frontier, Indians quickly found that these tacks, which were intended for holding cloth coverings on trunks or furniture, were ideally suited for personalizing firearms, tomahawks, war clubs, smoking pipes and other tools. Brass tacks rapidly became staples of the Indian trade up through the end of the century.

Although iron tacks can be seen on examples of firearms and gear, brass tacks were by far the most popular type of tack used for embellishment, undoubtedly because of its showy gilt coloring and the fact that it could be polished brightly—and this yellow metal retained its color without rusting! (One word of warning when encountering brass tacked weapons; modern tacks, often used to simulate an Indian-owned arm, are sometimes brass plated, rather than having solid brass heads.)

This Indian practice was occasionally employed by white frontiersmen. Famed explorer Kit Carson was but one of the better known whites who adorned at least one of his rifles with both tacks and other metal inlays.

Although round headed tacks most often dressed up Indian arms, tack shanks were sometimes hammered in instead. The head was then sheared off flush with the object’s surface, leaving just the tip of the shank to show, allowing the use of many “spots” spaced closer together, which formed an intricate design.

Regardless of whether round headed tacks or their slender shanks made up the artwork, a weapon’s adornment could range from a single tack to mark its owner’s identity to dozens of studs that represented popular motifs such as the U.S. Federal government shield, the Christian cross, the five-pointed Texas star, human or animal figures and sunburst or arrow designs.

Other forms of decoration were also used to repair broken stocks or for protection of the owner’s hands against extremely hot or cold metal parts such as gun barrels. These additions included rawhide wraps, paint, animals skins or hanging charms, like beads or even human trigger fingers.

Brass tacking, though, was by far the primitive man’s favorite form of bedecking his arms. While more documented Indian-owned firearms are unadorned, the cool looking weapons that have been studded with tacks have often come to boldly epitomize the “Indian gun.”

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

***BEST OF THE WEST 2015***

BEST FUN WITH A GUN

Editor’s Choice: Cowboy Fast Draw Association

Reader’s Choice: Single Action Shooting Society

BEST GUNLEATHER ARTISAN

Editor’s Choice: John Bianchi Frontier Gunleather

Reader’s Choice: El Paso Saddlery

BEST FIREARMS ENGRAVER

Editor’s Choice: American Legacy Firearms

Reader’s Choice: Doug Turnbull

BEST COWBOY ACTION PISTOL

Editor’s Choice: Colt Single Action Army

Reader’s Choice: Cimarron Thunderer

BEST COWBOY ACTION RIFLE

Editor’s Choice: Taylor’s Comanchero

Reader’s Choice: Henry Lever Action

BEST COWBOY ACTION SHOTGUN

Editor’s Choice: 1887 Winchester

Reader’s Choice: Stoeger Coach Gun

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Glen Swanson Collection –

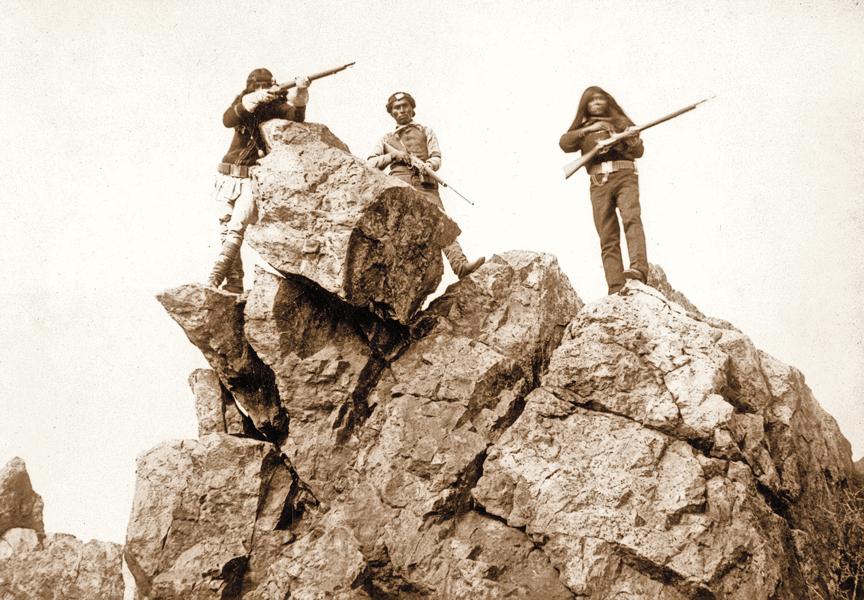

Giving you a commanding view of what ambushed settlers and soldiers saw when Apaches attacked, this C.S. Fly photograph taken in 1885 shows Apache scouts from San Carlos during the Geronimo Campaign. Apache Kid (center) was essentially adopted by Al Sieber, the chief of the Army scouts. In 1887, however, he got involved in a drunken altercation that ultimately earned him a firing squad death sentence. General Nelson Miles intervened and got Apache Kid a shorter sentence. An early release didn’t keep him out of jail, but Apache Kid redeemed himself by saving a jail guard from death.

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –

– Courtesy Glen Swanson Collection –

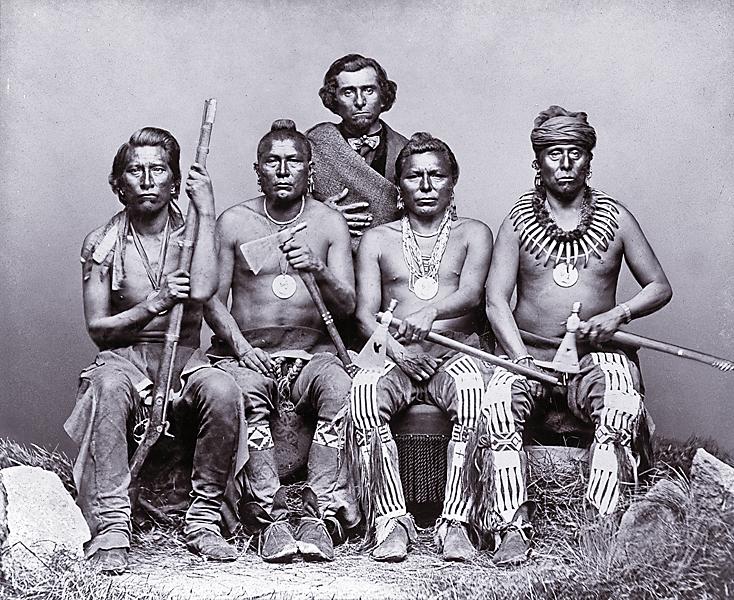

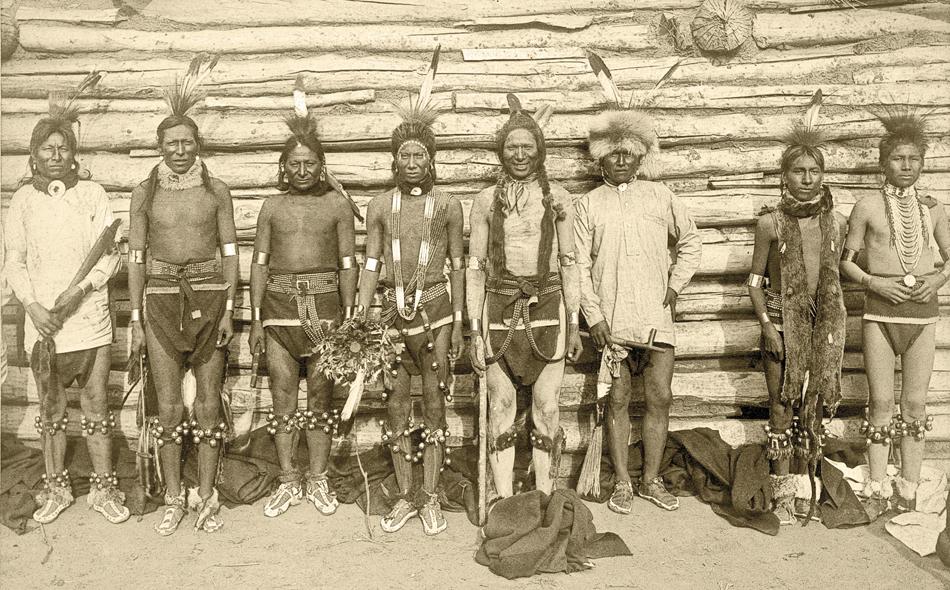

Armed to the teeth, these four Kitkahahki Pawnee brothers and U.S. Army scouts sit in front of interpreter Baptiste Bayhylle in this circa 1868 William Henry Jackson photo. (From left) Laroorutkahawlashar (Night Chief), Laroorasharroocosh (A Man That Left His Enemy Lying In The Water), Tectashacoddic (One Who Strikes The Chiefs First) and Telowalutlasha (Sky Chief).

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology –

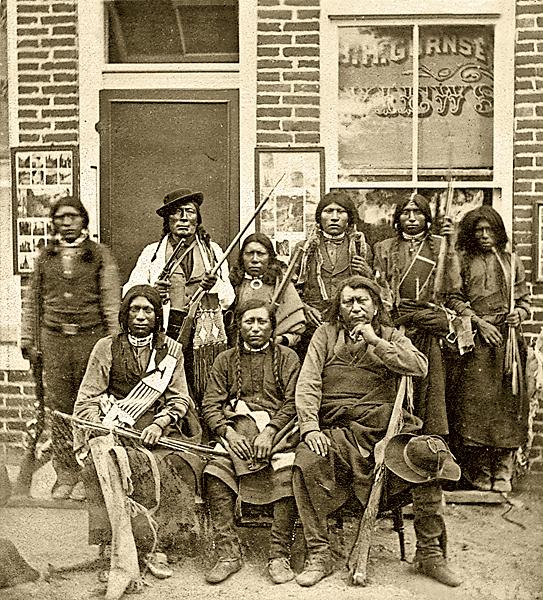

Ute Chiefs Jack and Colorow warned Maj. Thomas Thornburgh not to enter the Ute Agency with his entire force when he arrived at Colorado’s White River Agency in 1879 to investigate a rebellion against Agent Nathan Meeker. The post commander paid with his life. Standing with his Ute warriors, armed with rifles and bows and arrows, is Chief Jack (upper left), with Chief Colorow seated at lower right, in front of the B.H. Gurnsey photography studio in Colorado Springs.

– Courtesy Denver Public Library, Western History Collection –

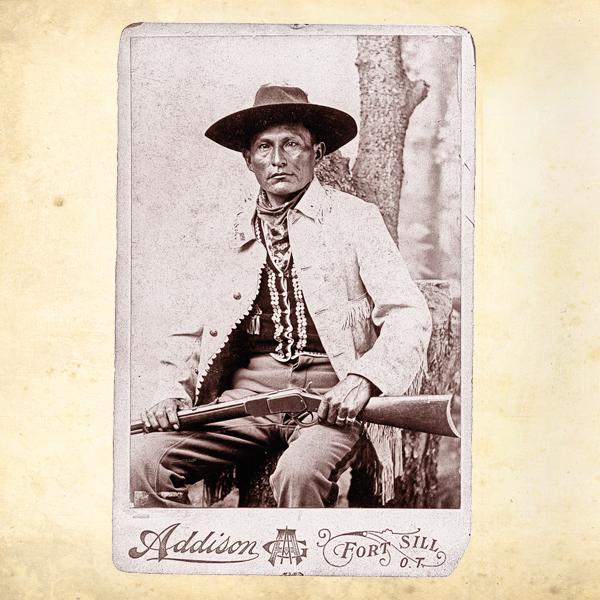

The son of one of the greatest Apache chiefs, Cochise, and the grandson of another, Mangas Coloradas, Naiche frequently joined Geronimo on his raids and surrendered with him in 1886. This photograph of him was likely taken at Fort Sill, Oklahoma Territory, where he enlisted as a scout in 1897. In 1913, he successfully moved his people from Fort Sill to New Mexico’s Mescalero Apache Reservation, which was more like their native homeland. He died there eight years later.

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin collection –

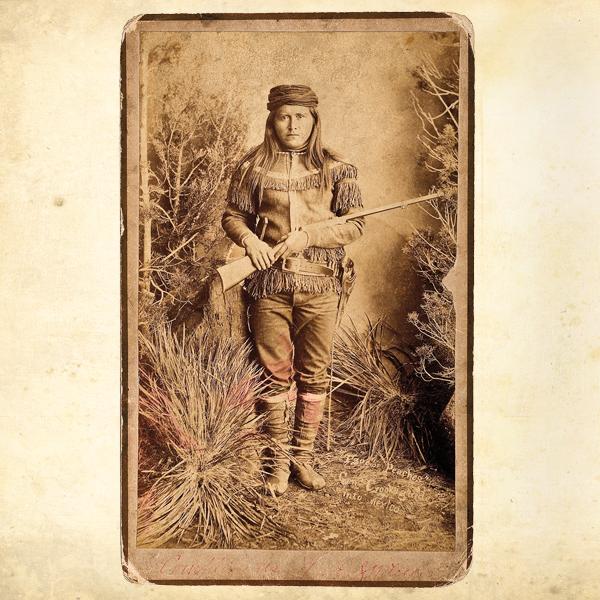

Shown holding his octagon barrel Frank Wesson rifle, with a holstered 1875 Remington revolver on his cartridge belt, Peaches helped Gen. George Crook track Geronimo and his Chiricahua Apaches during the Sierra Madre expedition into Mexico in 1883. El Paso Times correspondent A. Franklin Randall gave this photo a copyright date of May 16, 1884, four months after Geronimo had surrendered to Gen. George Crook’s Army and one year before the famed medicine man would escape again.

– Courtesy Cowan’s Auctions, December 9, 2010 –

Before Emmet Crawford was killed during his pursuit of Chiricahua Apache leader Geronimo in January 1886, he led these San Carlos scouts in the chase into Mexico. The scouts hold the standard issue rifle, .45-70 Springfield “Trapdoor” breech loaders.

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions, May 5, 2012 –

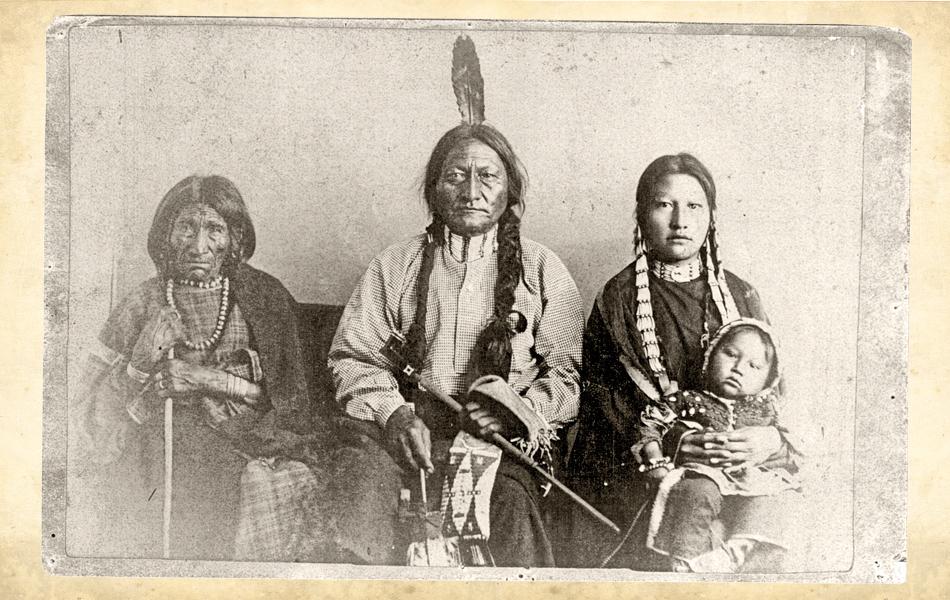

During one 1872 skirmish against Northern Pacific Railroad guards, with bullets flying all around, Hunkpapa Sioux Chief Sitting Bull sat on the ground, lit his pipe and smoked. He holds his long stemmed pipe, known as a calumet, in this photo of him seated between his mother and his eldest daughter holding his grandson. He famously witnessed the 1876 battle that killed George Custer and tragically died in 1890, when Indian Police attempted to arrest him at Dakota Territory’s Standing Rock Agency, for fear he would join the Ghost Dance movement.

– Courtesy Robert G. MCCubbin collection –

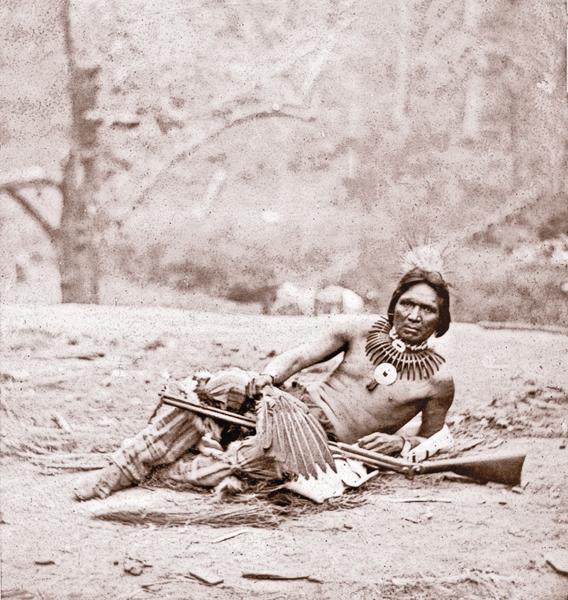

Reclining on the ground with his shotgun, Winnebago Chief Standing Buffalo wears an impressive grizzly bear claw necklace in this circa 1871 photograph likely taken on the Omaha Reservation in Nebraska, where his people were moved in 1863-64.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

A Nez Perce who fought in the 1877 war, Yellow Wolf holds a tomahawk and rifle in this 1909 photo. He blamed the war on Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s arrest of leader Toohoolhoolzote and for “showing us the rifle” during peace talks.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –