The original cowboys as we know them today, were the Mexican vaqueros. From Texas to California these superbly skilled horsemen could ride and rope with such adroitness that visiting spectators were astounded. There seemed to be no feat they couldn’t perform from the backs of their fleet-footed horses. Like the storied Plains Indian, “He only got off his horse to dance or to die.”

Much of the language the American cowboy uses today is derived from some corruption of the Spanish-Mexican language. “Buckaroo,” comes from the Spanish word vaquero, while “lariat” is a derivative of the words la reata. Spanish-Mexican influence is seen in other words like corral, rodeo, remuda, bronco, caballo and mustang, all of which are almost pure Spanish. Other words were Americanized by the English-speaking cowhands from north of the border. Chaparreras was shortened to chaps. The joquima became “hackamore,” the mesteno was corrupted into mustang and sombra, a word meaning shadow or shade, for sombrero or hat.

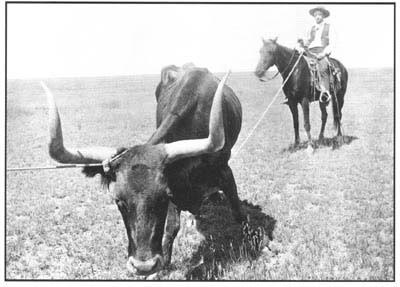

To this day it ain’t the boots and hat that makes a cowboy and it ain’t the fancy pickup, spurs and high-crown hat. It’s the ability to handle a rope with uncanny skill. It began with those vaqueros on the Texas plains. With reatas as long as 110 feet he could take a dally on a running steer from sixty feet.

The word dally is an American corruption of the Spanish dar la Vuelta, which means to take a turn around the saddle horn. Once the loop is cast around the cow’s horns, the roper takes a couple of counterclockwise turns around the saddle horn. When the slack comes out of the rope. There is a serious hurt awaiting the roper who gets his thumb or fingers caught in the slack. In an instant the roper loses a thumb or finger. That’s why some ropers fancy the Texas hard and fast style. The rope is anchored to the saddle horn. If something goes wrong all the roper stands to lose and that’s only temporary, would be his rope and maybe his saddle.

The colonization of Texas in the 1820s opened a whole new way of life for the Americans. The techniques of ranching in the Southwest were nothing like they’d ever seen in the heavily wooded lands east of the Mississippi River. Sprawling ranches were spread over hundreds of square miles and thousands of longhorn cattle roamed the open ranges. The open range was no place for a man on foot.

The cattle industry had been small, and ranchers primarily harvested cattle for their hide and tallow. There was no way at the time that meat could be preserved long enough to get it to a market.

The techniques of ranching on those Texas plains was like nothing they’d ever seen. However, it wasn’t many years before the newcomers adapted to the lifestyle and most became as skilled as the Mexicans. A whole new breed of American was born and destined to become the root of western American folklore, legend and myth. He was the last grand image of adventure and romance, the rugged human spirit from which legends are made.

During the Civil War the numbers of cattle in the brasada country around the Nueces River in southwest Texas had been breeding and running wild for years. The number of unbranded cattle was estimated to be between three and six million. When the men returned from the war the state was in an economic depression with thousands of cattle and no market to sell them. At the same time the livestock in the east had been denuded by wartime demand and there was a huge market if there was some way to get the cows to the stockyards in Chicago. Cattle that sold for as little as two dollars a head in Texas fetched forty dollars a head in the Windy City.

At the same time the Kansas and Pacific Railroad was building west from Missouri. Joseph McCoy, a cattle broker from Illinois, built extensive corrals in the town of Abilene, Kansas. He persuaded the railroad load cattle there and haul them to Chicago. “Texas Tick Fever” had caused Missouri and Kansas to quarantine Texas cattle in the 1850s so he induced the Kansas legislature to not enforce the law on Abilene. He sent agents to Texas to spread the word that if they’d gather cattle, he’d buy all they could provide. The Texans were desperate and having no other choice and only the word of a Yankee, they took a leap of faith and went to work. In 1867, 36,000 longhorn Texas cattle crossed the Red River on their way to Abilene. McCoy proved to be a man of his word. Some claim he was the man who gave birth to the saying, The Real McCoy. The legend was about to begin.

In the early days of the Long Drive, some of those longhorns had run loose for so long they were fifteen or twenty years old before they headed for the market. Since the horns keep growing for the life of the beast, many were known to reach lengths of eight and nine feet across. The results of a cowboy or his horse being gored by one of could be fatal.

To say a longhorn was pernicious is like saying when a grizzly bear gives you a hug he just wants to dance. Speaking of grizzlies, out in Old California the Mexicans used to match them with bears and wager on the outcome. European big-game hunters used to stalk and hunt the wily beast for trophy. More than one found its way to the den or game room of some marquis.

It wasn’t the cow that made the cowboy unique, it was the horse. The basic tool needed for working cattle was a range mongrel of mixed heritage. They were range animals running wild until they were four of five years old, standing only twelve to fourteen hands high and weighing seven hundred to nine hundred pounds. These wild mustangs were inbred with U.S. Cavalry remounts and Eastern-bred horses. In the spring they were corralled and ready to be “broke” or “busted.” There was no time for patience or pampering. They had to be ready for the cattle drives beginning in late spring.

This “boot camp” for horses was to break their wild spirit could only last four to six days. If the ranch happened to have and experienced cowboy to do the busting. If not, the boss hired a specialist bronc buster who traveled from ranch to ranch breaking horses at five dollars a head. The lesson was to instill fear and respect for the rider.

One bronc buster explained it this way, “If a buster was getting fifteen bucks a head instead of five, horse fighting would be a heap safer for horses and men. Bosses won’t stand for a fifteen-dollar finish on a thirty-dollar horse”

A cowboy had his own personal string of horses to use while going up the trail. Most cowboys developed a genuine affection for their mounts and during slack time around the campfire, spent a great deal of time extolling their abilities. There was his swimming horse, used when fording swollen rivers and his speed for friendly wagers. Usually, his favorite was his sure-footed and alert night horse who carried the tired cowboy through his two-hour watch. It was said a good night horse could walk the entire watch smoothly enough to allow the waddie to sleep the entire time. Since this was the golden age of prevarication, he might go as far as to claim his pony would deliver him back to his blankets, kneel and gently deposit him into his blankets without even awaking him. But wait, there’s more; that night horse would even go over and wake the next cowboy who was to go on watch.