A bright orange glow spread across the eastern New Mexico horizon on the morning of March 9th, 1916. The sleepy border town of Columbus was slowly coming to life. In the pre-dawn, the first group of Mexican soldiers cut through the barbed wire and crossed quietly into the United States. They began moving towards the little town of Columbus, three miles to the north.

About a mile from the slumbering town, General Francisco “Pancho” Villa divided his five hundred raiders into two columns. One set out for the U.S. Army post at Camp Furlong, while the other went forward to strike the town of Columbus. Today, nobody is certain what motivated him.

Villa’s army took heavy casualties in the raid and the U.S. reacted quickly. By the next day American troops were on the move. A punitive expedition led by General John Pershing was preparing to invade northern Mexico. This action would introduce Americans to a different kind of warfare, aerial. The original name of the Air Force, from 1914 to 1918, was the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.

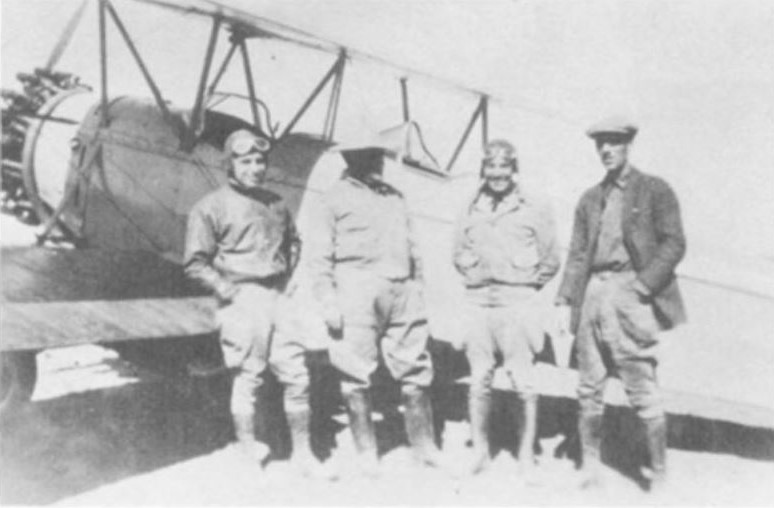

The American military lagged far behind in its acceptance of the newfangled machine as a weapon of warfare. During one period, the United States ranked fourteenth in the world in air forces. Finally, in 1916, under the leadership of Captain Ben Foulois, our air force was put to the supreme test. There were only eight Curtiss JN-2 machines, and Foulois’s young pilots were subjected to such indignities as having their planes blown down by the strong Mexican winds, and worse. One pilot was forced to land in a cow pasture in the dead of night. He barely escaped after being pursued by an unfriendly bull. Still another had to prevent some of the locals from burning holes in his craft with cigarettes after he crash-landed near their village. With local citizens throwing rocks at the hapless pilots after landing and propellers that wouldn’t keep the planes in the air, our air corps was literally blown out of the sky in Mexico. The amazing thing about the whole episode is that there were no fatalities suffered by the pilots during the entire conflict.

Pancho Villa was still fighting wars of the 19th century. When his vaulted Dorados tried to charge through a battlefront strewn with barbed wire, the German-trained machine gunners cut his “Dorados” to pieces at the Battle of Celaya.

But he was a bit of a visionary when it came to aerial warfare. He hired an American aviator named Ed Parsons to train his young pilot-recruits for aerial combat and since there were no airfields around, their training field was a rocky cow pasture. During the demonstration landing Parsons touched down on the uncurried turf. The craft bounced violently before coming to a halt in a cloud of dust. When the air cleared, Parson looked around and Villa’s fledging young pilots had disappeared off into the wild green yonder. Villa’s “Air Force,” so to speak, never got off the ground.

One of the most remarkable incidents in the southwestern lore occurred the Christero War in March 1929. The residents of Bisbee found themselves with ringside seats to a revolution that year as the Mexicans were once again locked in one of their periodic struggles. Railroad cars were pulled up alongside the international border town of Naco and the locals climbed on top to view the contest. Except for an occasional stray bullet which scattered the spectators, the Mexicans put on quite a show. Usually when daylight ended, the combatants also had good sense to put aside their differences and quaff down cerveza in one of the local cantinas until dawn and the revolution once again called upon the gladiators to report for duty at their trenches. It has been said that on occasion the two opposing factions even frequented the same cantinas during off-duty hours and exchanged war stories together.

With the federales entrenched on three sides of Naco, the rebels saw fit to hire an American mercenary pilot named Patrick Murphy and an old nondescript airplane to bomb the defenders. It should be noted that American soldiers of fortune were taking part in the revolution against the expressed wishes and desires of the U.S. Government.

Since merely keeping the plane aloft was a full-time job, the pilots took on young Mexican boys as bombardiers. The bombs were leather bags full of nuts, bolts, screws, and explosives. A fuse was attached and when the mini-bomber made its run over the trenches, the lad merely had to touch his cigarette to the fuse, drop the bag over the side, and wait for the expected result. Like the bombing raids of earlier times, it was extremely doubtful if any significant conclusion could be drawn from the blasts, but they had put on quite a show for the spectators. As for the bombs, surely there were better, more efficient ones available, but not to the impoverished rebels.

There is no great monument or physical barrier to mark the international boundary between Naco, Arizona and Naco, Sonora, beyond an old fence and a dusty street. It came to pass that aviator Murphy, in his zealousness, strayed over to the American side, where he dropped several of his suitcase bombs, one landing in Newton’s Garage, where it destroyed a Dodge automobile that had been stored for safekeeping by a Federale general, and another hitting in front of the Phelps-Dodge store. It is said that one of the local sharpshooters stepped out and shot the plan down with his rifle just as it was making another run. Pilot Murphy survived the crash and was later arrested and jailed in Nogales, but somebody forgot to lock his cell and the colorful Irishman faded into obscurity.