Mining Camp author Brete Harte wrote: “The ways of a man with a maid are strange, but tame, when compared to a man with a mine when buying or selling the same.”

And Mark Twain added: “A mine is a hole in the ground, owned by a liar.”

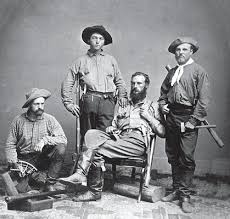

During the last half of the 19th century the West, especially places like California, Arizona, Colorado and Montana were perceived as veritable treasure troves of gold and silver. They provided fertile ground for hucksters, shysters, con men and bamboozlers. Many dollars were made selling worthless mining properties to unsuspecting greenhorns.

A favorite method used in unloading a useless claim or mine was called, “salting.” The seller would buy ore from a productive mine and carefully scatter it about his non-productive property in hopes of closing a sale on the claim. Others might take a shotgun, load the charge with gold dust and blast the walls of the shaft, impregnating them with particles of gold. Gold was malleable and would imbed itself into the rock, giving the worthless claim a highly mineralized façade.

The game of buying and selling a worthless mine could conceivably become a matter of who could outwit whom. The seller might impregnate the walls with gold but the wise buyer might ask to have the walls blasted to see what was inside the rock. Trying to stay one step ahead, the seller could install gold into the headsticks of his dynamite and when the charge went off, the interior would be salted. To counter this, the buyer could insist they use the dynamite sticks he’d brought along for just such an occasion.

The smart buyer also brought along his own geologist. Not surprisingly, many times an entire community would plot against the buyer since the economic stability of a region might hinge on the successful sale.

Bichloride of Gold, or a chemical liquid, was used for medicinal purposes such as alcoholism and kidney ailments. When taken internally it will pass through the body, exiting the body with high assay value. A seller bent on cleverly salting his mine could load himself on the substance and salt any crack, crevice as nature moved him.

A prospective buyer came to Arizona around 1900 to investigate a property near Prescott. It was owned by an old prospector who saw an opportunity to retire in luxury. He carefully salted the mine with his 12-guage shotgun, replacing the lead with fine placer gold. He was diligent, thorough and totally dishonest.

The dandies from Boston arrived accompanied by a young mining engineer fresh out of Yale. The mine was inspected and the salted ore was taken to be assayed. The property was thoroughly scrutinized and the dudes made only one mistake. They showed the glowing assay reports to the old prospector, who was so over-whelmed he changed his mind and refused to sell.

A group of five Irishmen working in a mine in which they also owned stock decided to inflate the value of the stock by spreading a rumor the mine had hit a rich vein of gold. The stock went up and all five sold at a tremendous profit. Soon after, the stock value went in the tank, costing the owner a chunk of money. It didn’t take long for the owner to figure out what the five Irishmen had done but he couldn’t prove it.

So he told them he’d like them to stop by his office the next day and swear on the Holy Bible they hadn’t manipulated the stock market. “No Irish Catholic would dare place his hand on the Holy Bible and lie,” he declared. The three righteously swore they wouldn’t have done such a dishonest thing.

The miners were given their jobs back and returned to the mine. One day a few weeks later the owner was in his library browsing through his library and while reaching for a book he accidentally knocked his Bible off the shelf. When it hit the floor the cover fell off and underneath was a copy of Webster’s Dictionary.

It seems those clever Irishmen had sneaked into his office the night before their testimony and “salted” his Holy Bible.