No sooner had a prospector’s pick struck paydirt in some remote, canyon in old Arizona, a town was bound to spring up nearby followed by a host of new arrivals, anxious to help separate some poor sucker from his poke sack. They called it “mining the miners.”

Among the first were the whiskey peddlers, soiled doves and land speculators. Hot on their tails were the lawyers. Disputes over mining claims and real estate properties required the presence of the much-maligned frontier lawyers. Litigation became the single most lucrative business in the mining camp and some of those early lawyers were the best money could buy. They weren’t always welcome. One prospector quipped, “We didn’t need laws until the lawyers got here.”

In the boom town of Tombstone, the lawyer’s occupied a row of low-slung adobe offices on 4th Street, located conveniently between the saloons on Allen Street and the courthouse on Tough Nut. The area was somewhat affectionately referred to as “Rotten Row.” Local punsters declared that none of their lawyers could “pass the bar” without first stopping in to belly up.

During its heyday Tombstone was never wanting for good attorneys and none was more capable or better-liked than the irrepressible Allen R. English, an eastern-educated attorney from an aristocratic Maryland family. He displayed signs of brilliance early, graduating from law school while still a teen. He drifted west, arriving in Tombstone in 1880 at the age of 20 where he took a job working as a hard-rock miner. He made the nightly rounds of the honky-tonks along Allen Street where he met prominent attorney, Markus Aurelius Smith, who recognized his talent and took him in as a junior partner. Smith groomed his protégé well both in the practice of law and the night life.

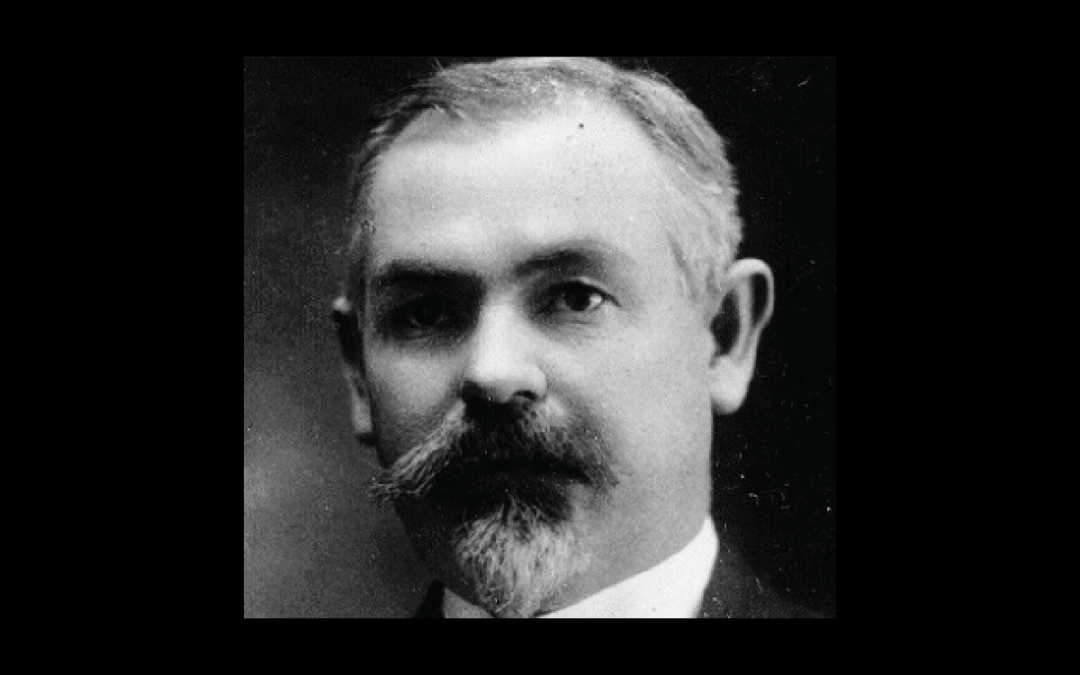

English, dressed in a cutaway coat and striped trousers, was blessed with a magnificent crown of hair, sweeping mustache, neatly-trimmed Van Dyke beard and a deep, resonant voice. Standing over six-feet tall, he moved around the courtroom with the grace of a ballet dancer. Blessed with charm, formidable wit and a great sense of humor, the so-called “Courtroom Colossus” quickly became one of the most popular men in Cochise County.

English could hold a jury spellbound with whispered emotion or with the voice ringing with resonance, or he could launch into a speech of fire and brimstone that would have done a Southern Baptist preacher proud. He could maneuver a jury by flattery, cajolery, crying or begging. He took great liberties with both judge and jury. For example, when pleading a case he might pause, lean over the jury box, address one of the jurors he knew and say, “Jim! Give me a chew of tobacco!”

He could spit tobacco juice with all the aplomb of a muleskinner too. Old timers claimed he could unleash a stream over his shoulder and hit the inside of a cuspidor at ten feet. These courtroom exhibitions became known, (with apologies to Charles Dickens), as “English’s Great Expectorations.”

One time Judge Alfred Lockwood, father of future Arizona Supreme Court Chief Justice Lorna Lockwood, sentenced him to 30 days for contempt. English unleashed a fifteen-minute torrent of eloquence that included Shakespeare, Latin and Greek poets and the Almighty.

Judge Lockwood, tears streaming down his cheek could barely contain his laughter.

“All right, Mr. English, I’ll reduce it to fifteen days.”

As he was escorted out of the courtroom he turned to the audience and declared, “See, I got him to cut it in half!”

English proved such a nuisance he was released after serving just three days.

Even when in the most bibulous condition his florid command of the English language, stinging wit and courtroom antics kept opposing lawyers in a state of consternation and spectators in hysterics. It’s no wonder folks traveled for miles to see him perform before judge and jury.

At times strong liquor seemed to improve his ability to try a case. One time he was defending a gunslinger named Wily Morgan on a murder charge while also nursing a painful hangover. The court recessed for lunch just before the closing arguments so English went to his favorite watering hole for more of the “hair of the dog that bit him.”

By the time court was ready to convene he was passed out on the barroom floor. Someone brought a wagon to the front door and English was stretched out in back and hauled to the courthouse, carted up the backstairs, arriving just in time for the closing arguments. He opened his eyes, then slowly stood up, focused on the jury and went into the most masterful piece of oratory folks in those parts had ever heard. When it was over, the jury returned a verdict of innocent.

When friends and admirers rushed up to offer congratulations, they quickly realized English had no idea what had just transpired.

Always a friend of the oppressed Allen R. English was a colossal pain in the posterior to prosecuting attorneys. Someone once called him outspoken.

“He may be out-maneuvered, out-smarted, and out-thought,” a weary prosecutor remarked, “but he is never out-spoken.”